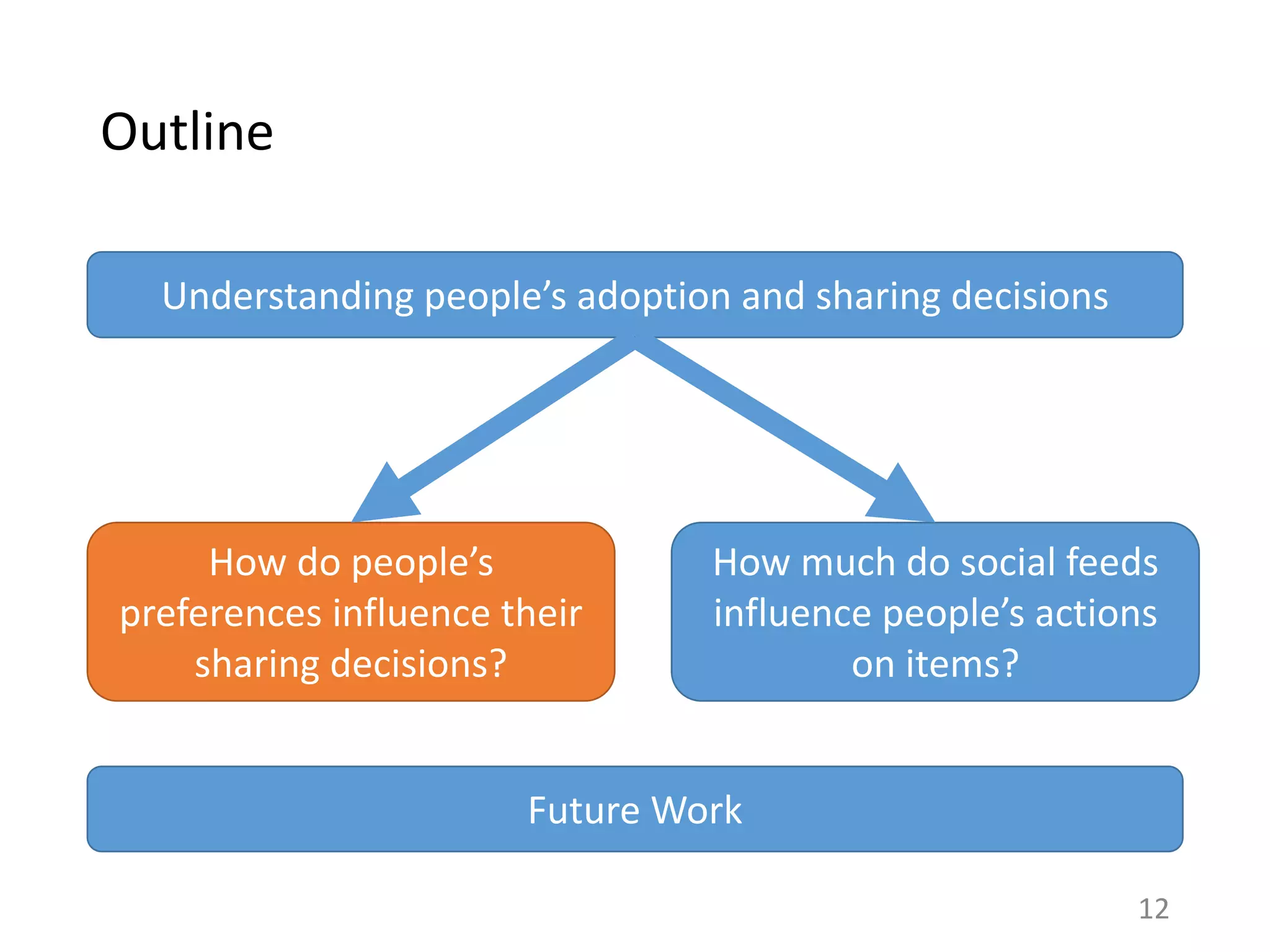

The document summarizes research on understanding how personal preferences and social influence affect sharing behaviors on social networks. It presents three key findings:

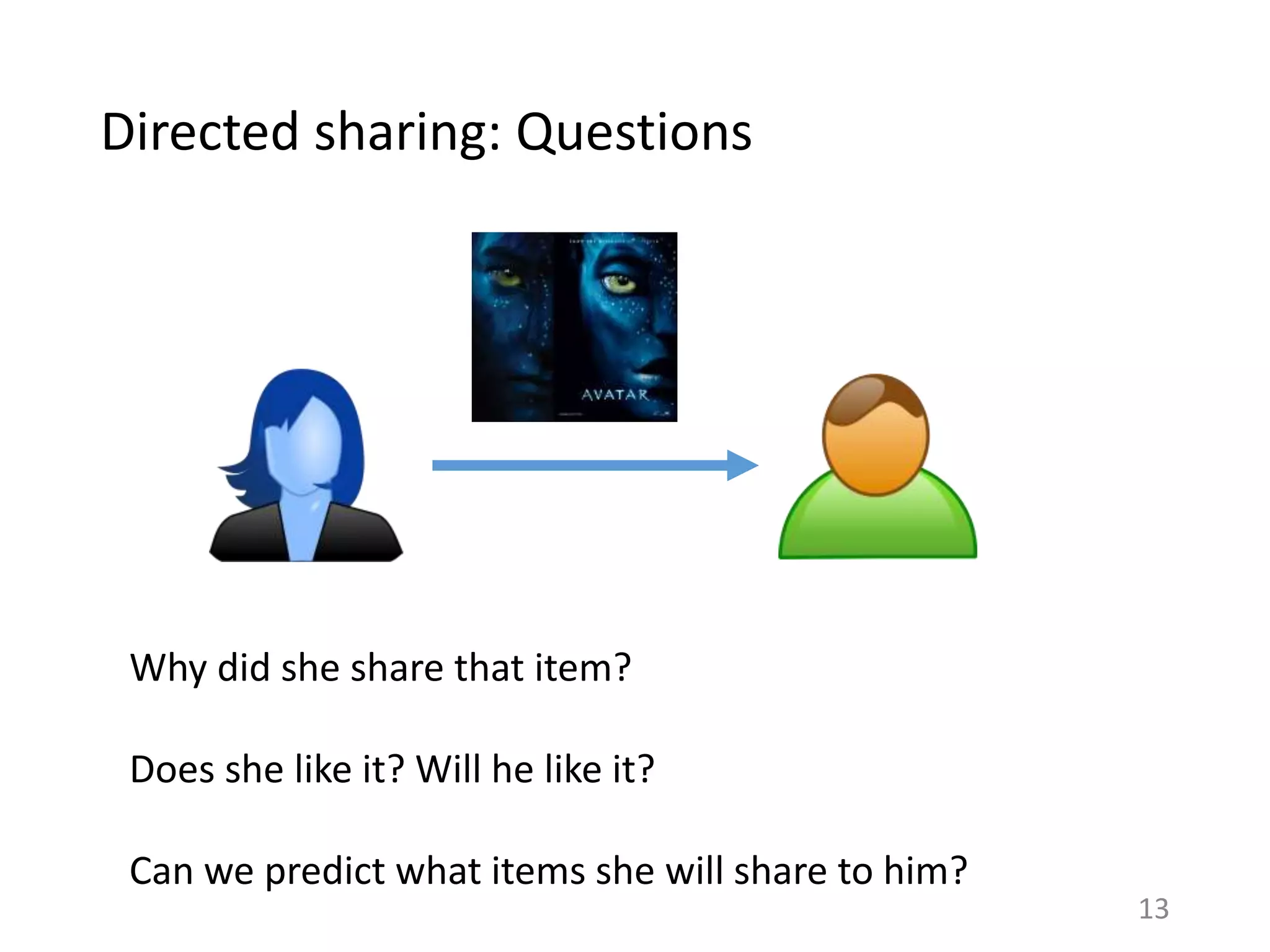

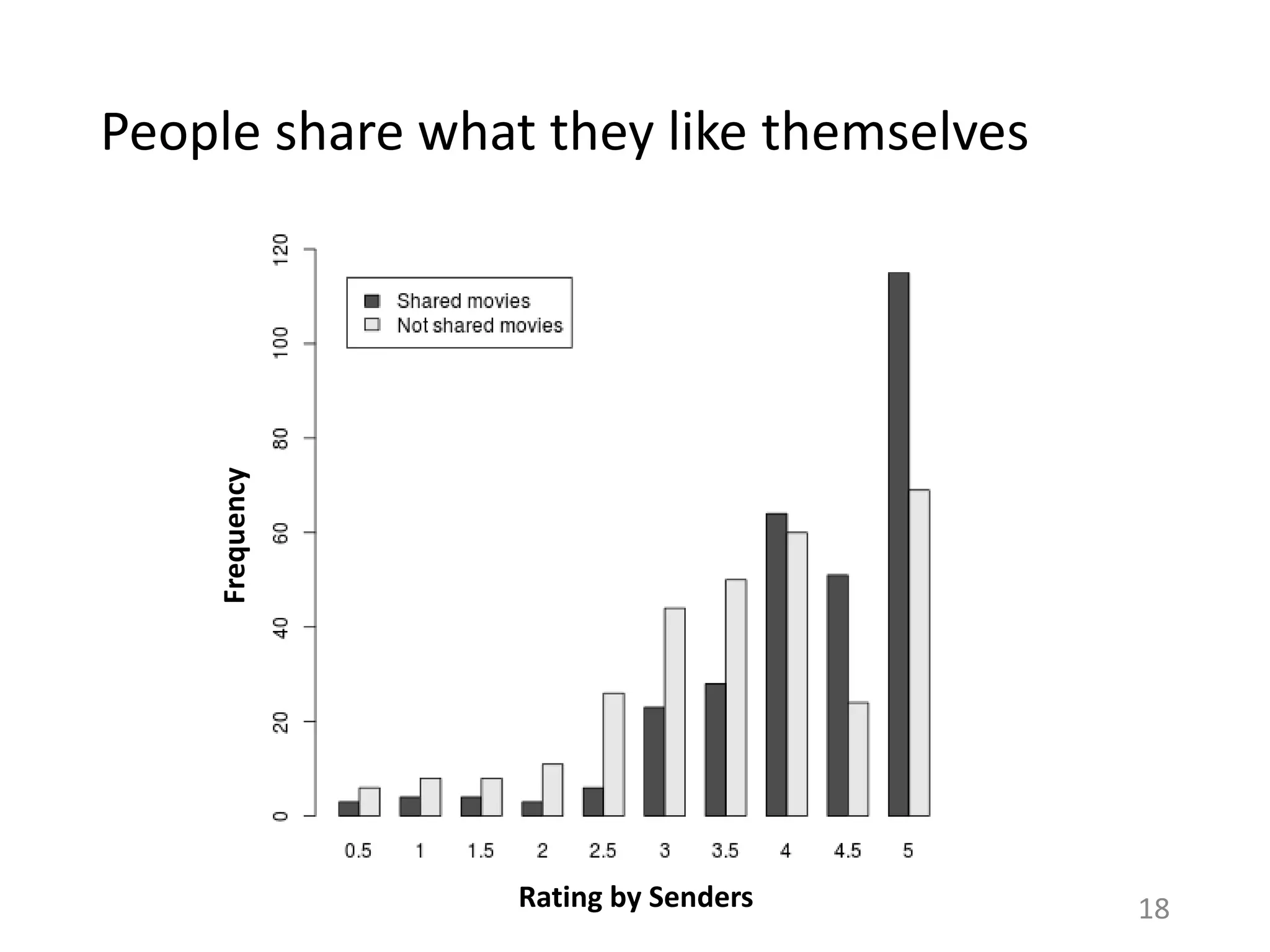

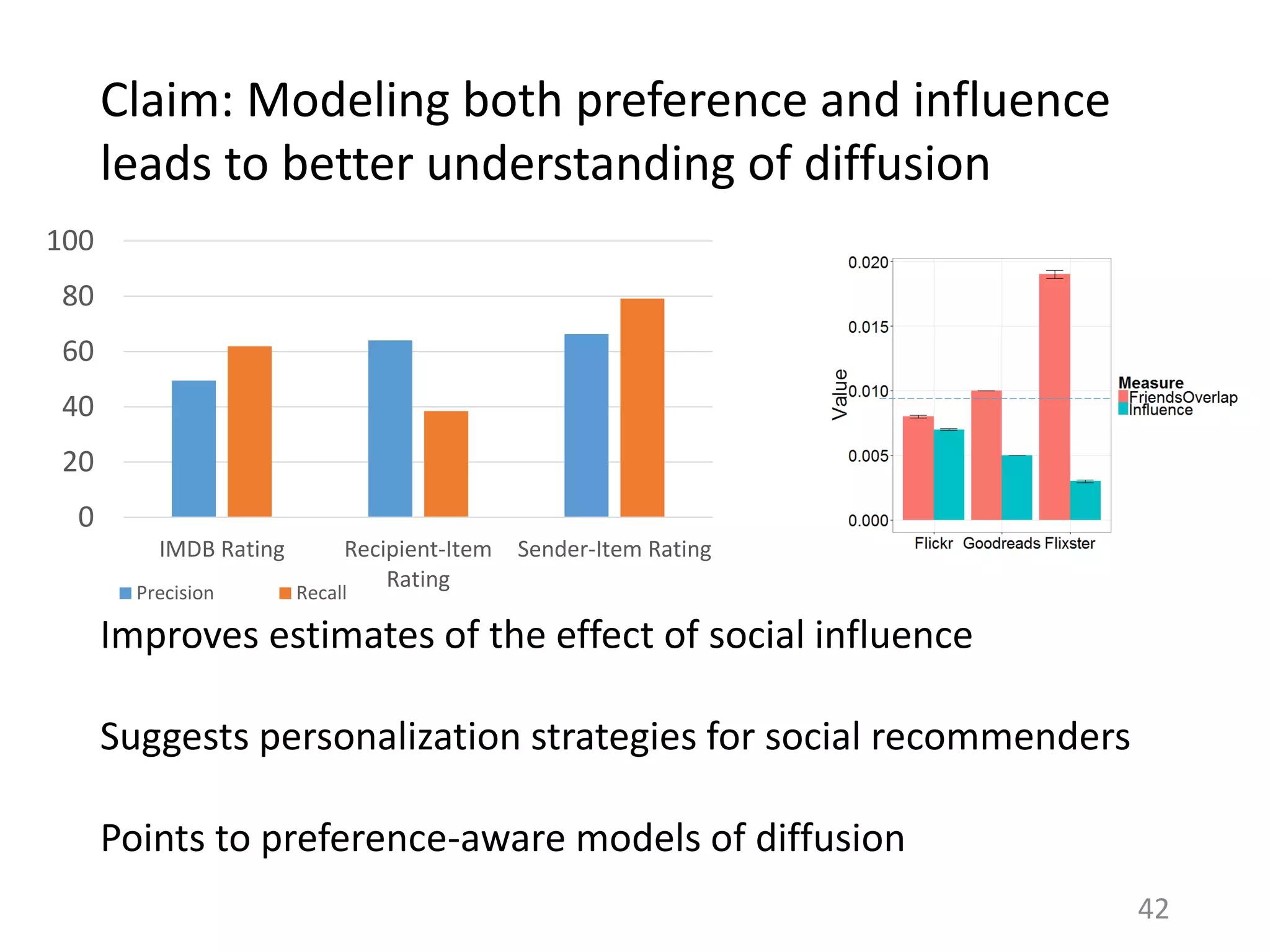

1) Personal preferences dominate individuals' decisions about what content to share, with people more likely to share items they themselves like.

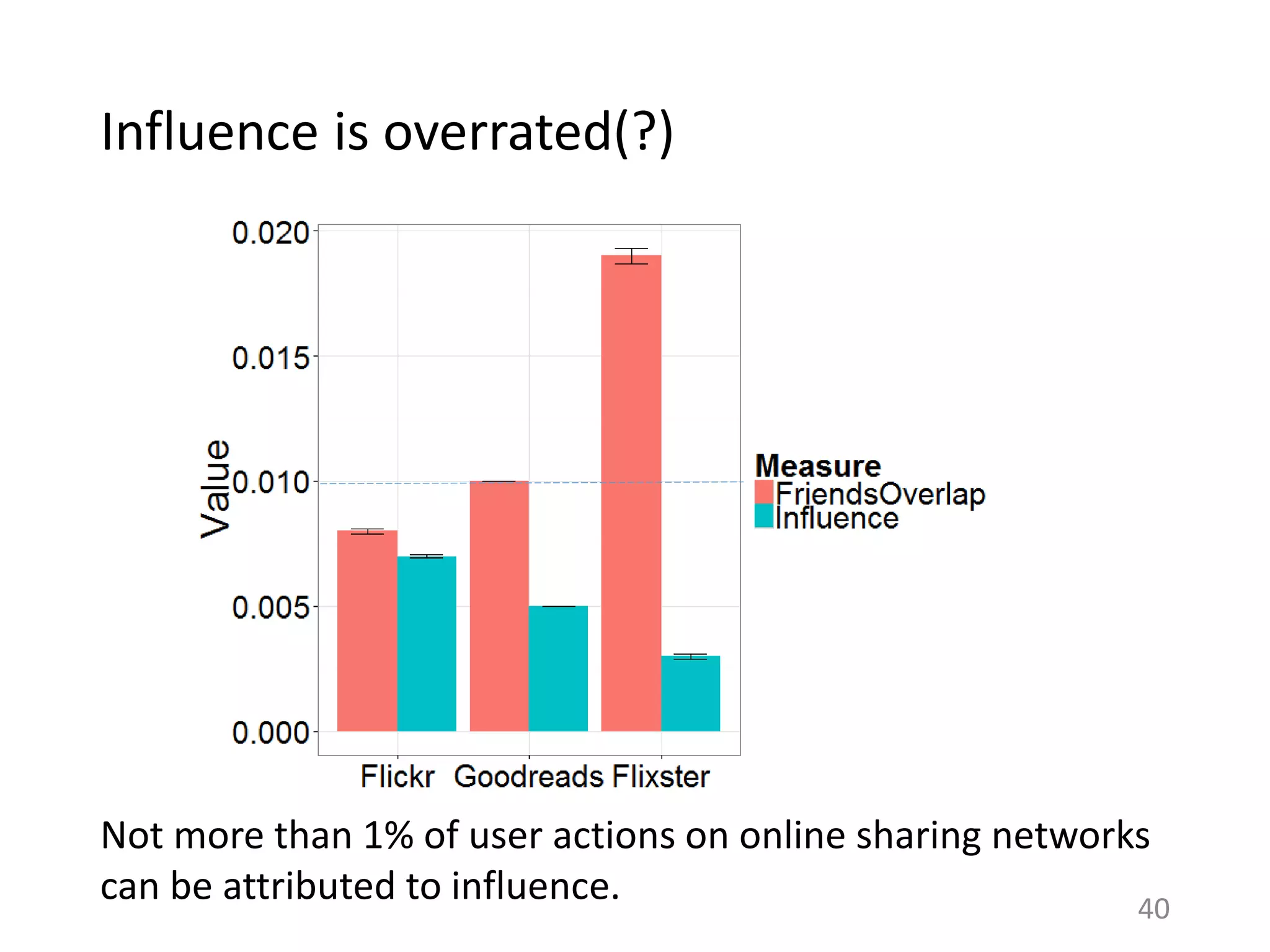

2) Less than 1% of peoples' actions can typically be attributed to social influence from friends, with influence being overestimated in prior work.

3) Modeling both personal preferences and social influence may lead to a better understanding of how content spreads on networks and help improve recommendation systems and diffusion models.

![Two ways of looking at the world

7

RECOMMENDATION SYSTEMS

Model individual preferences of

users

Does not consider explicitly the

effect of sharing or social processes

[Ma et al. ‘09, Konstas et al. ‘08,

Jamali and Ester ‘10, Sharma and

Cosley ‘11, Sharma and Yan ‘13]

NETWORK DIFFUSION

Model spread of items in a social

network, one at a time

Does not consider an individual’s

preferences over items

[Watts ‘02, Kempe et al. ‘03, Bakshy

et al. ‘09, Lerman and Ghosh ‘10 ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-7-2048.jpg)

![Example 1: How do friends-based

recommendations compare with those computed

from the full network?

9

[Sharma-Gemici-Cosley 2013]

MOVIES

MUSIC

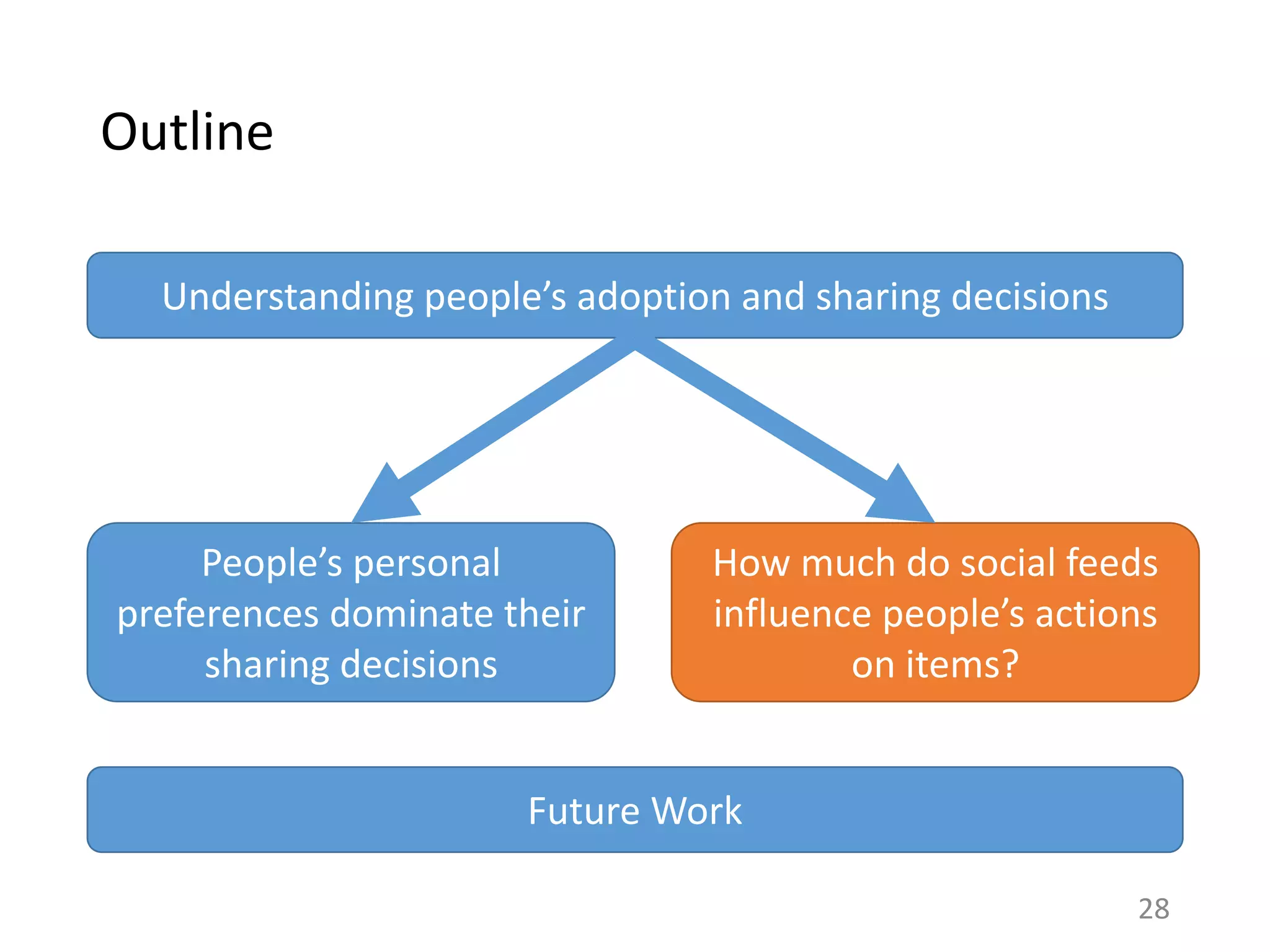

HASHTAGS

# Friends ~ 100-500

# Non-friends ~ 50k](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-9-2048.jpg)

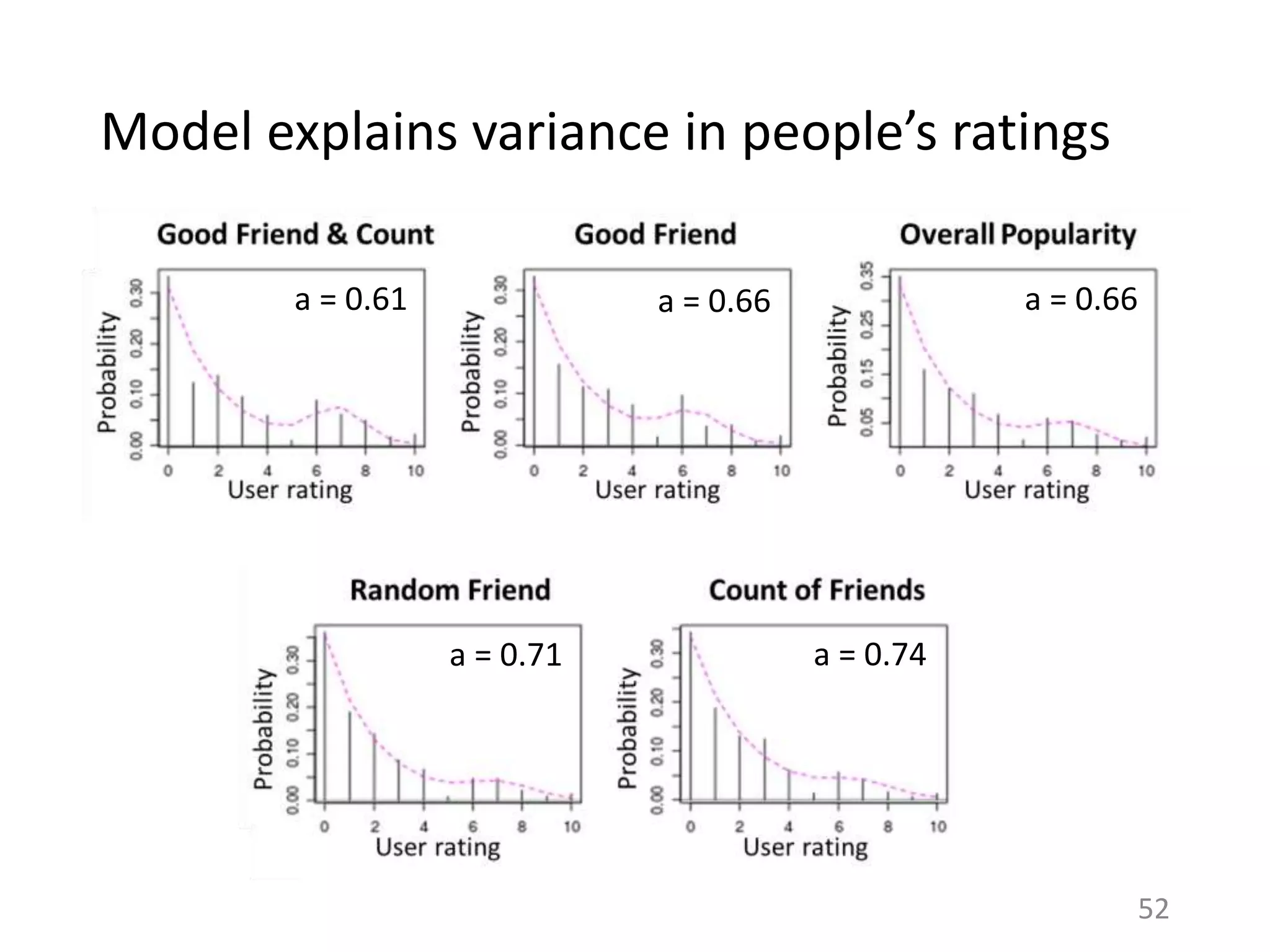

![Example 2: Which social explanation would

influence you to try out a musical artist?

10

10 of your friends like this Dan and Levent like this

a = 0.61 a = 0.74a = 0.66

10 of your friends like this. Dan likes this.

[Sharma-Cosley 2013]

MUSIC

a = Rigidness](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-10-2048.jpg)

![My contributions

EXPERIMENTAL

• The effect of personal

preference and influence

on people’s decisions

– Item adoption [WWW ‘13]

– Item sharing [CSCW ‘15]

11

OBSERVATIONAL

• Aggregate effect of

people’s activities over the

sharing network

– Extent of preference

locality [ICWSM ‘13]

– Influence estimation [In

submission to CSCW ‘16]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-11-2048.jpg)

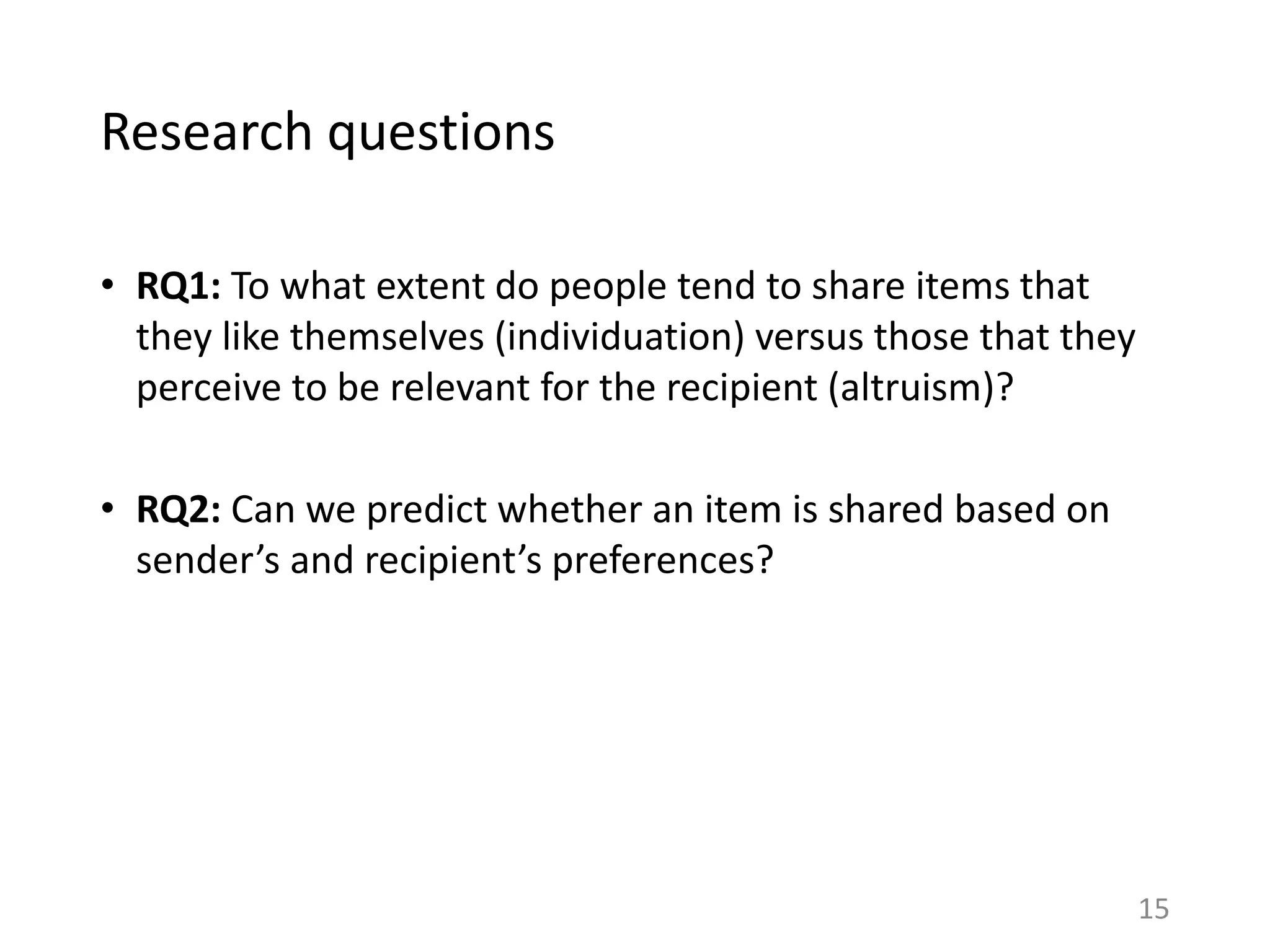

![Two motivations for sharing

Word-of-mouth

Individuation

– Establish a distinct identity

for oneself

Altruism

– Help others

[Dempsey et al. 2010]

Online Content sharing

Sender’s preferences

– Sender shares what she

likes

Recipient’s preferences

– Sender shares what recipient

would like

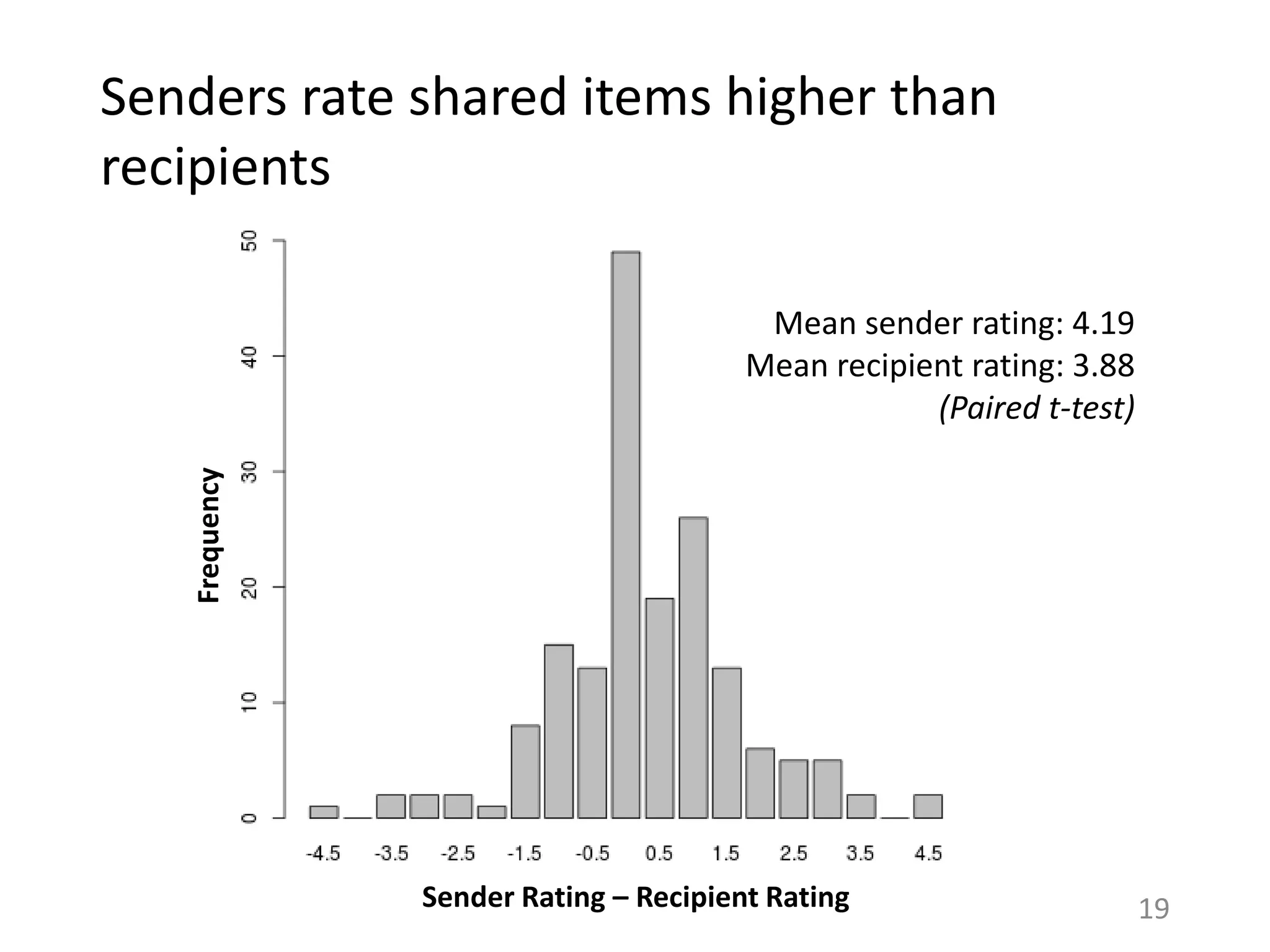

Comparing sender’s rating versus recipient’s rating for a

shared item can indicate the relative effect of these

motivations. 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-14-2048.jpg)

![Ratings for shared items depend on item set

shown

Recs.

for

me

Recs.

for

partner

Other-ShownOwn-Shown

22

Recs.

for

me

Recs.

for

partner

Both-Shown

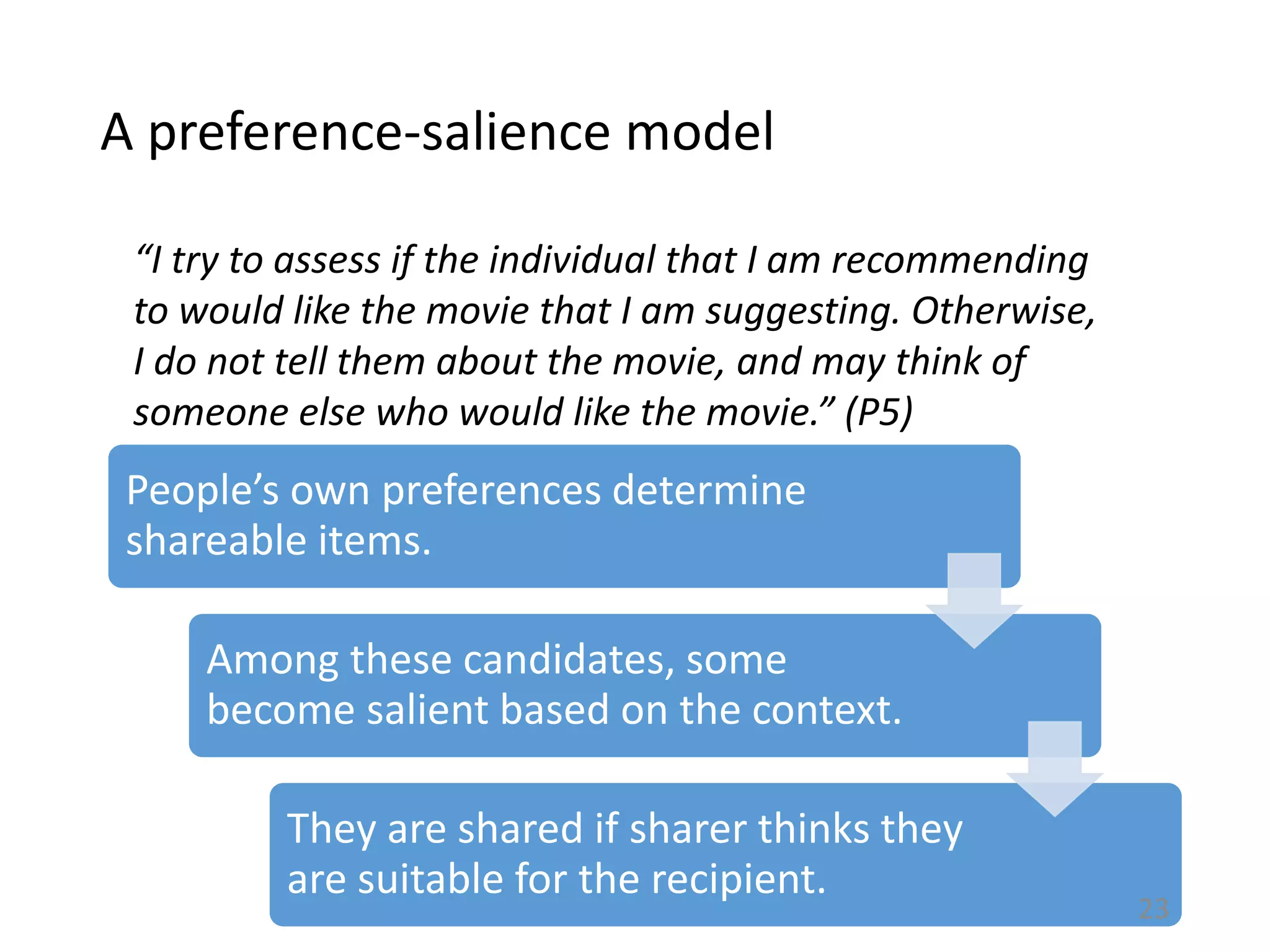

Sender’s µ= 4.4

Recipient’s µ = 3.7

(***)

Sender’s µ = 4.06

Recipient’s µ = 4.28

(ns)

Own-Algo: (***)

Other-Algo: (ns)

[Paired t-test]

Salience of items impacts what gets shared.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-22-2048.jpg)

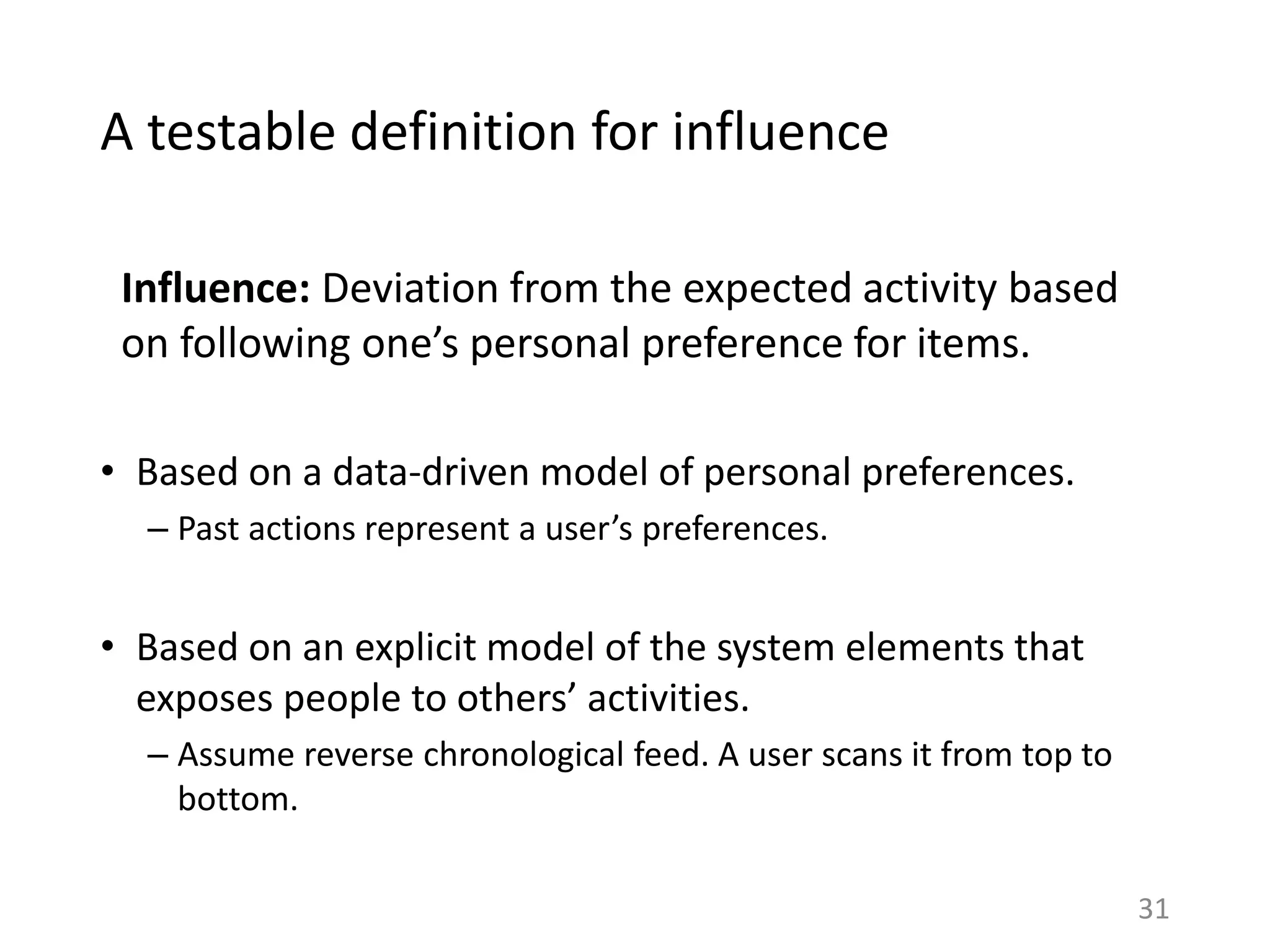

![How much and why do people copy feed

actions?

29

Virality is rare, vast majority of shares spread

to zero or one degree [Goel et al. ‘12].

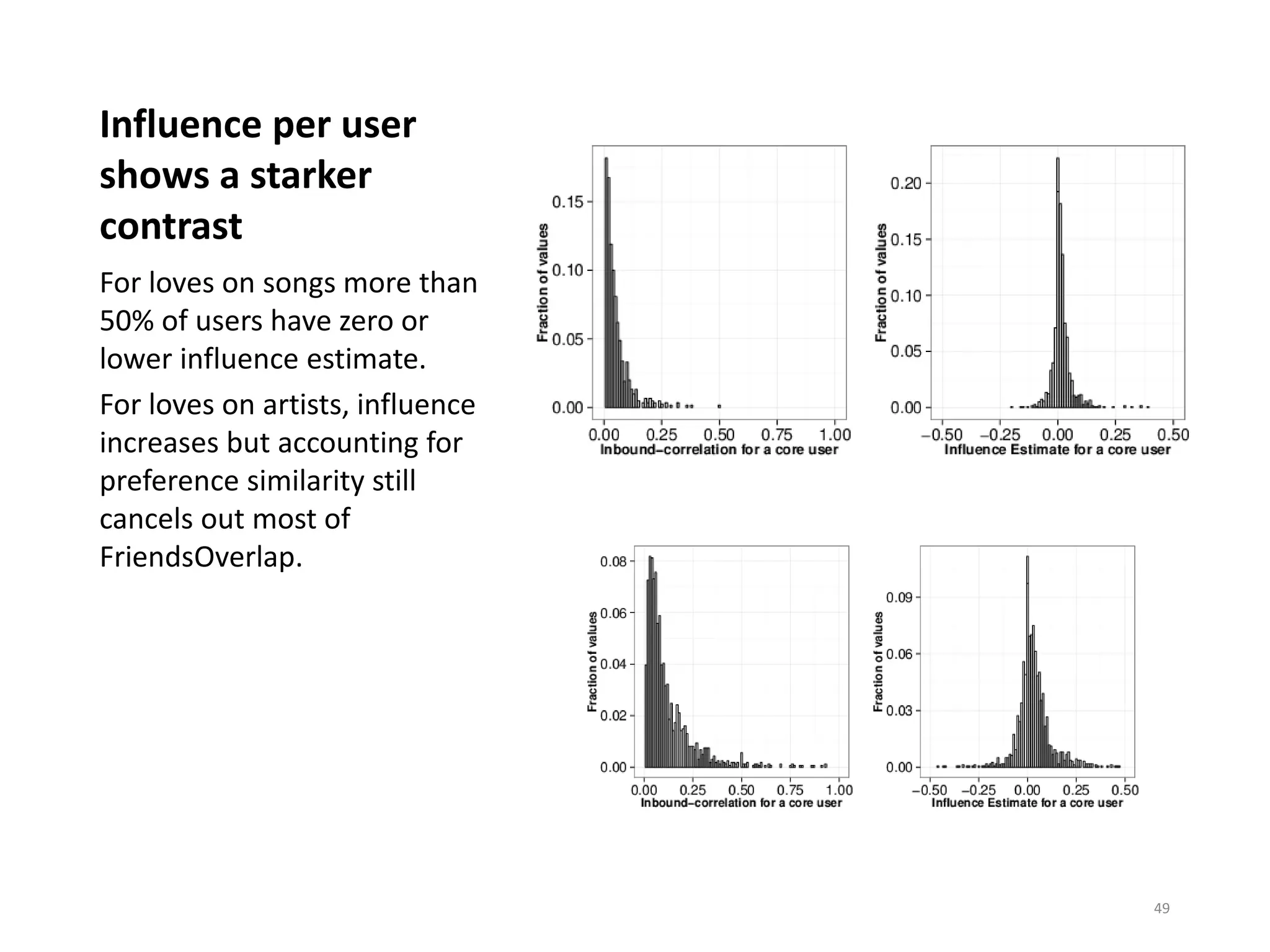

Most studies on social media find a nontrivial

correlation between the activities of a user

and her friends [Sharma and Cosley ’13].

Q: Can we ascribe how many copy actions are

caused by influence from friends?

In general, hard to infer from observational

data alone [Shalizi and Thomas ‘11].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-29-2048.jpg)

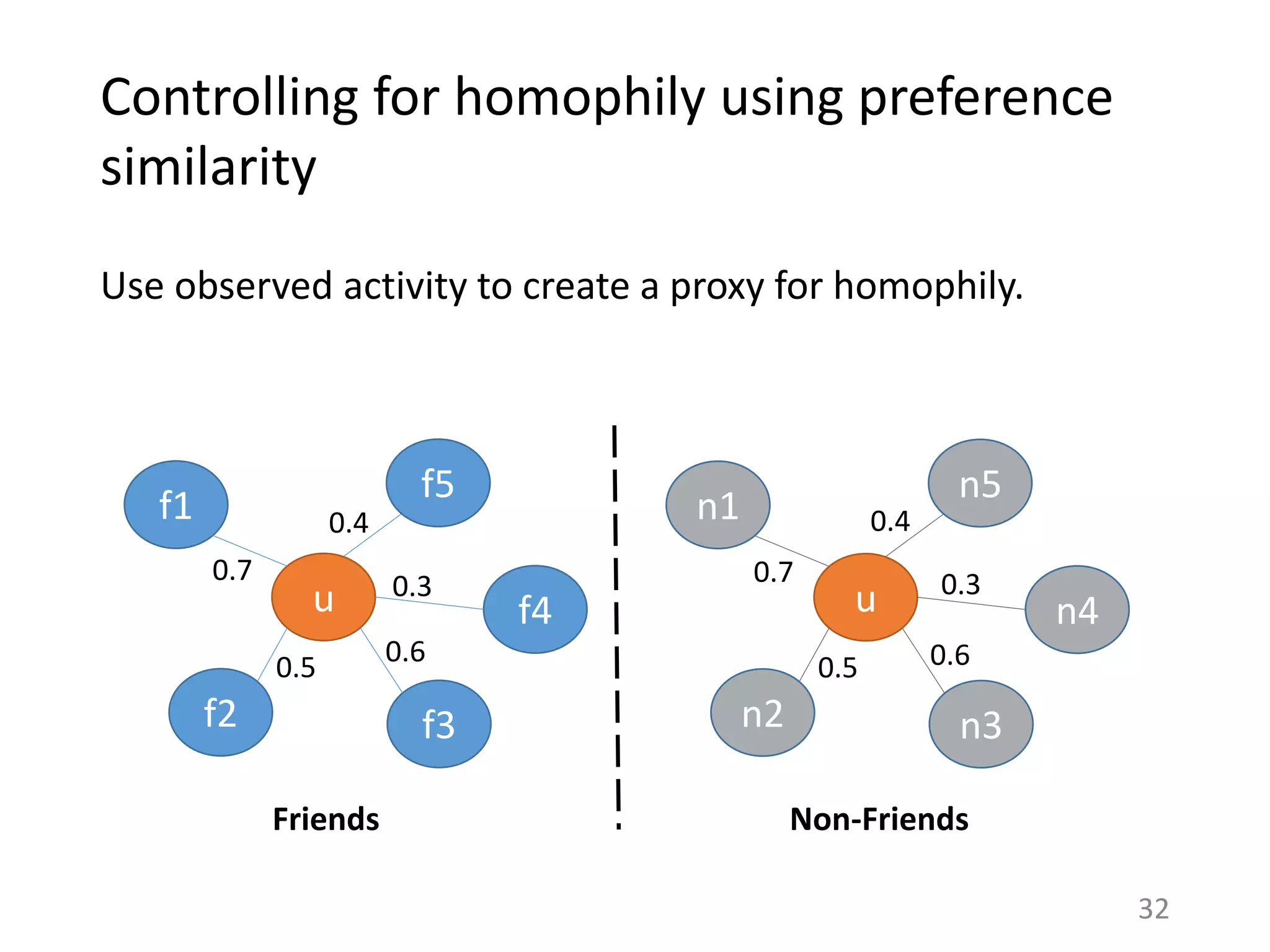

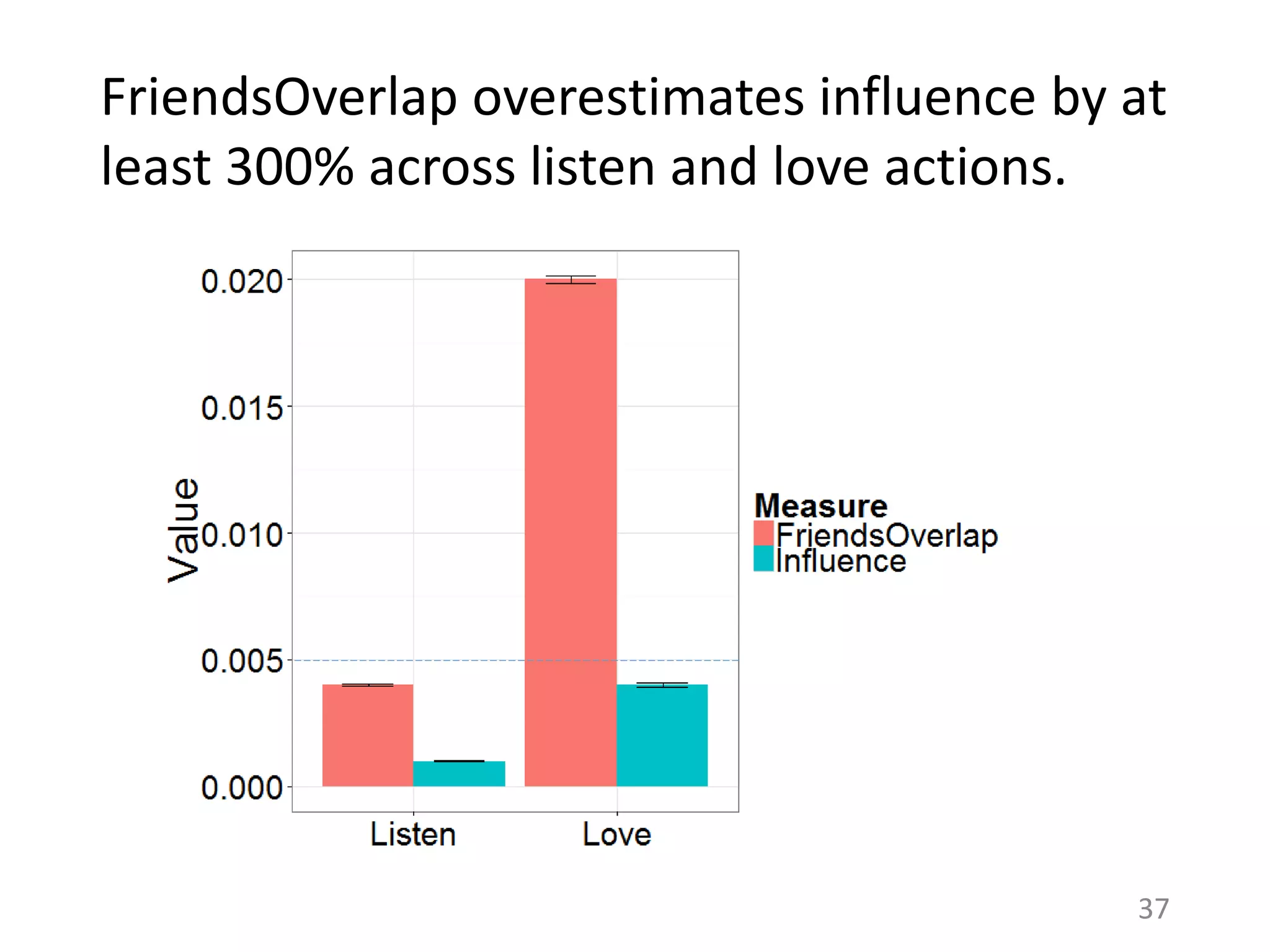

![Many processes for generating a common

action by friends

• Social Influence

• Homophily

30

Without controlling for homophily, we may

overestimate influence [Aral et al. ’09, Lewis et al. ‘12].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-30-2048.jpg)

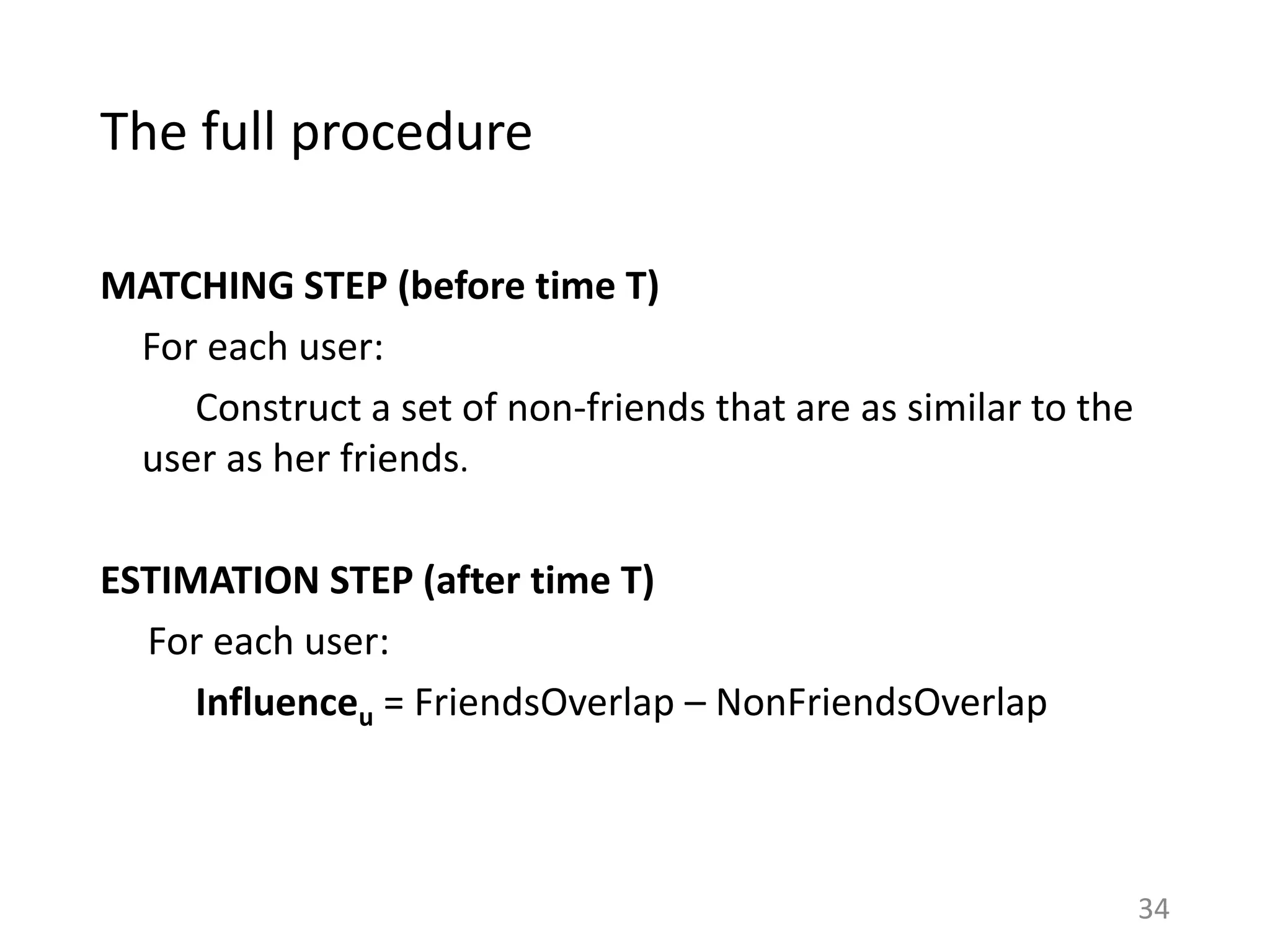

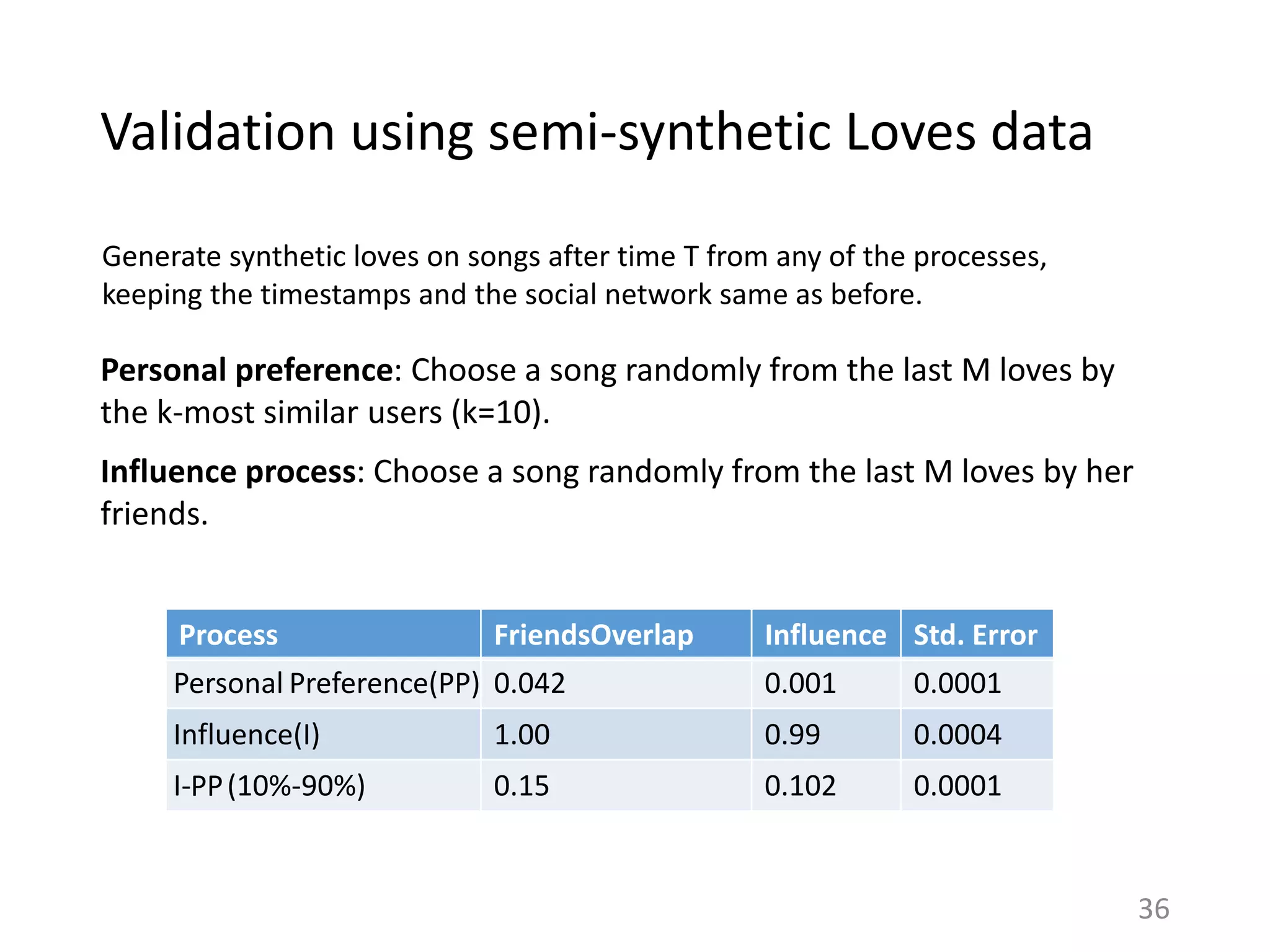

![Estimating the actions due to influence

For each action by a user, construct feeds from friends and

non-friends containing their last M actions respectively.

Friends Overlap = Fraction of actions done by u that are also

in the friends’ Feed

(Naïve measure of influence [Ghosh et al. ‘10, Bakshy et

al. ‘11]).

NonFriends Overlap = Fraction of actions done by u that are

also in the non-friends’ Feed.

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-33-2048.jpg)

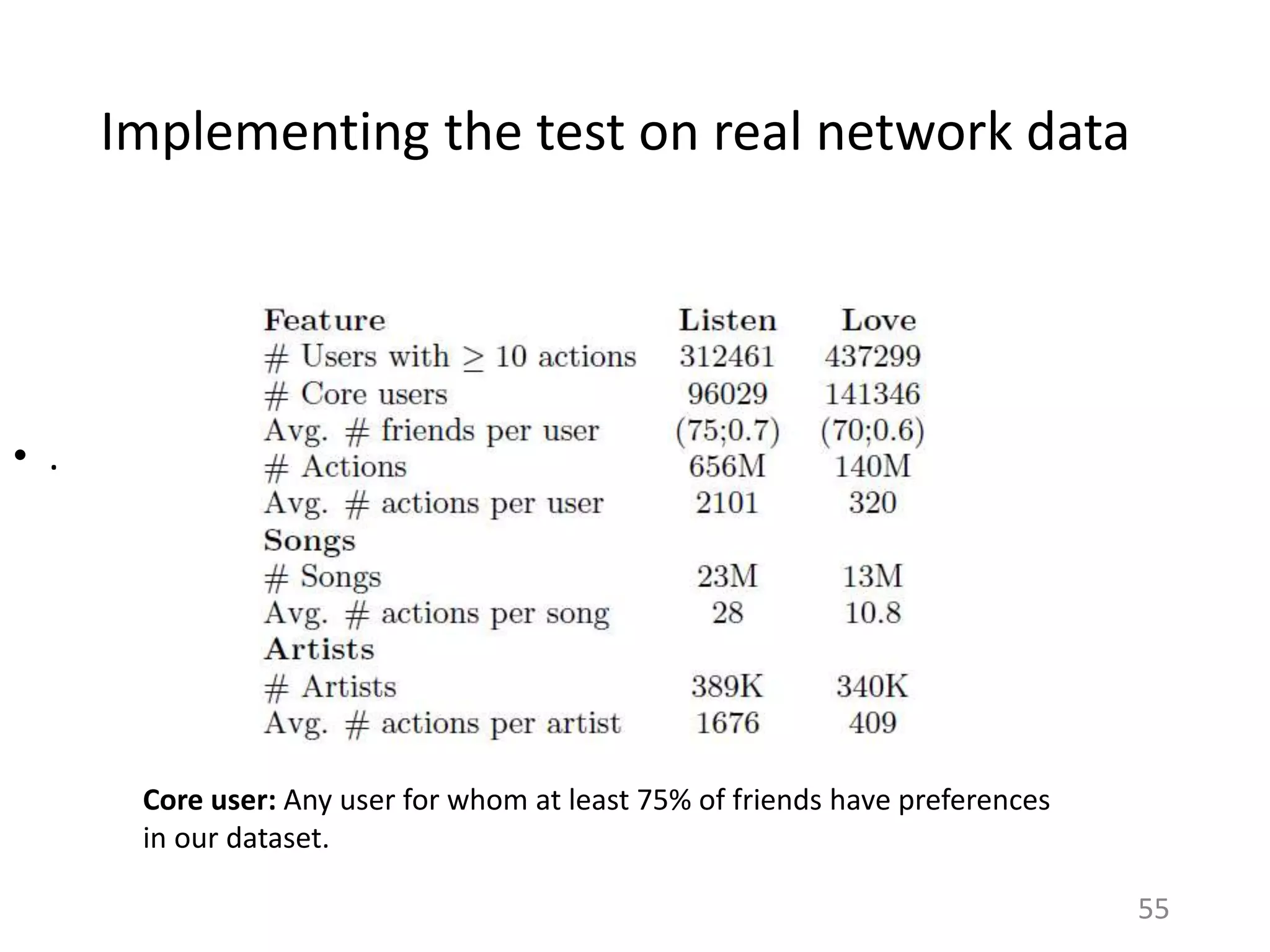

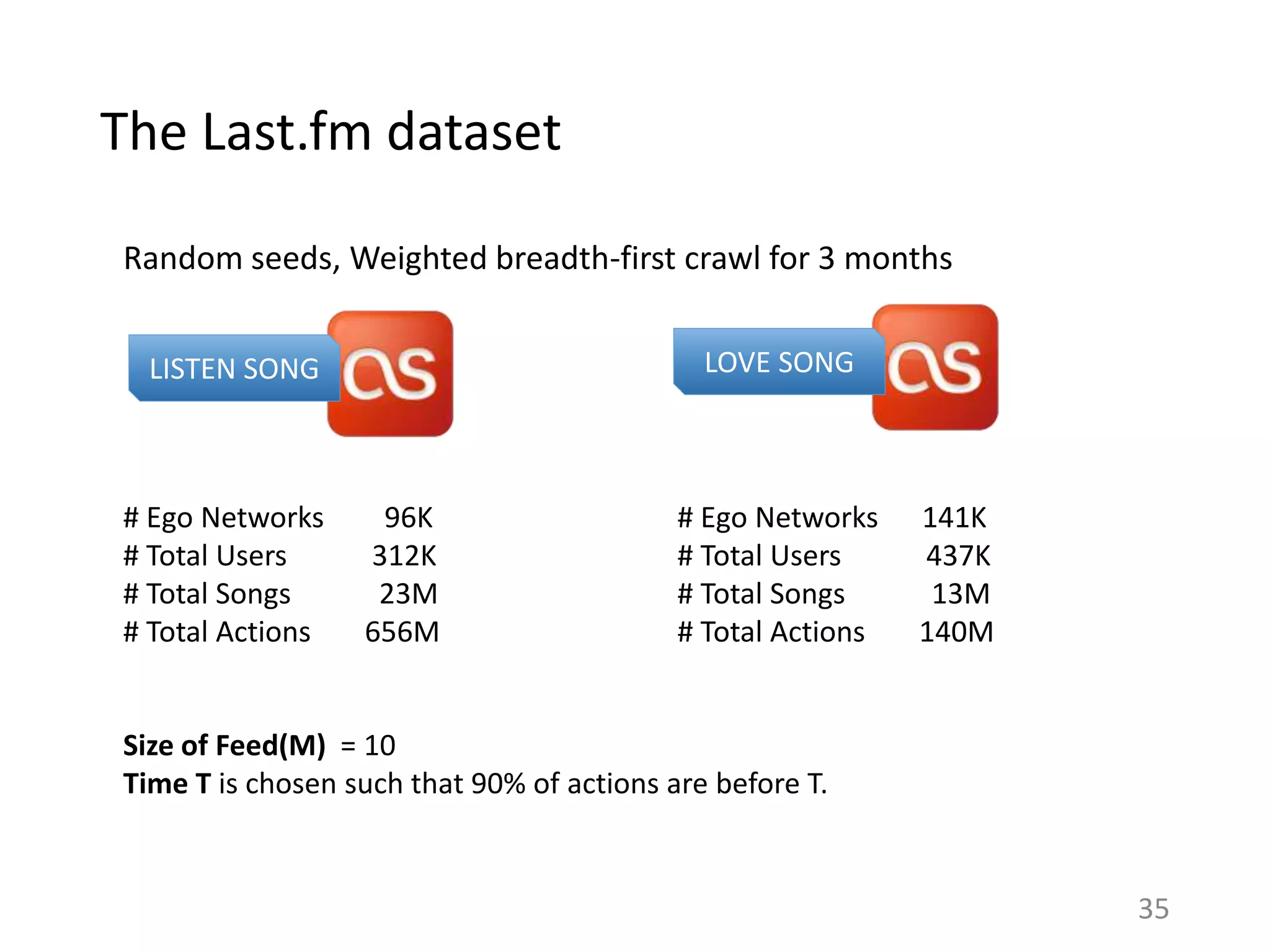

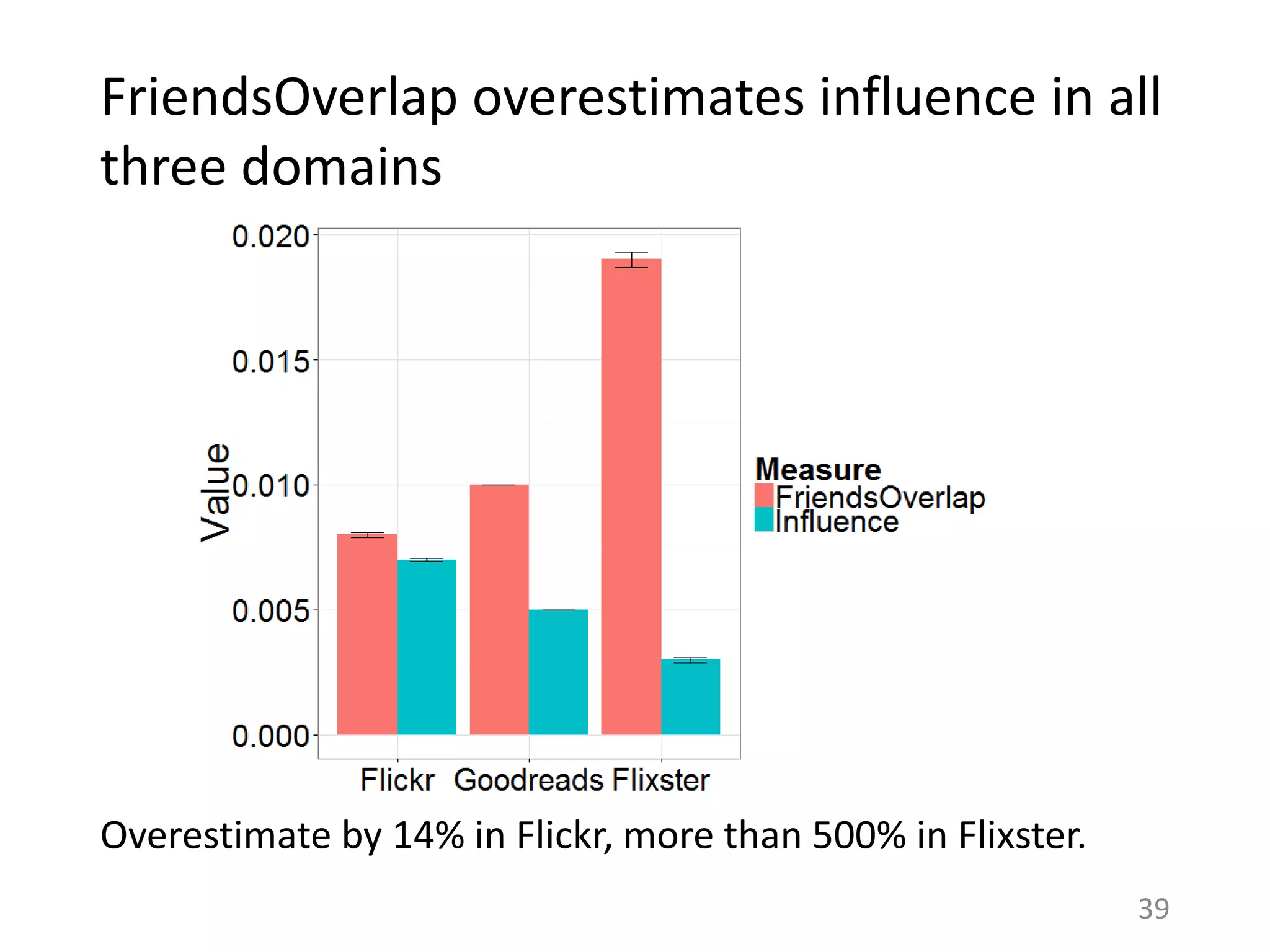

![Is this specific to Last.fm?

38

Assumptions of Influence Estimation:

Reverse chronological feed

Preferences as a proxy for homophily

Can be applied to any sharing platform that shows friends’ activities in a

(loosely) reverse chronological order.

RATE BOOKS

FAVORITE

PHOTOS

RATE MOVIES

# Ego Networks 252K

# Total Users 252K

# Total Items 1.3M

# Total Actions 28M

# Ego Networks 49K

# Total Users 50K

# Total Items 48K

# Total Actions 7.9M

# Ego Networks 175K

# Total Users 183K

# Total Items 11M

# Total Actions 33M

[Huang et al. ‘12] [Jamali and Ester ‘10] [Cha et al. ‘09]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-38-2048.jpg)

![Directed sharing: More altruism?

• Meformers versus informers: ~80% of content shared on

Twitter was about the user [Naaman et al. 2008]

• In directed sharing, there is a known recipient

– Expect altruism to be more important

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-45-2048.jpg)

![Design implications

Recommender systems for effective sharing

• Recommending what to share, who to share it to.

E.g., Feedme system [Bernstein et al. 2010]

Diffusion models with directed sharing

• Accounting for sender and recipient preferences

46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-46-2048.jpg)

![A simple decision model for ratings

User's receptiveness to

an explanation.

[Effect of Explanation]

User's discernment in music.

[Base Decision Process]

Coldplay

+

Amit Sharma likes

this.

50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/b-examcornell-150610152114-lva1-app6891/75/The-interplay-of-personal-preference-and-social-influence-in-sharing-networks-Ph-D-defense-talk-50-2048.jpg)