The Dynamic Brain An Exploration Of Neuronal Variability And Its Functional Significance 1st Edition Mingzhou Ding Phd

The Dynamic Brain An Exploration Of Neuronal Variability And Its Functional Significance 1st Edition Mingzhou Ding Phd

The Dynamic Brain An Exploration Of Neuronal Variability And Its Functional Significance 1st Edition Mingzhou Ding Phd

![3

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further

Oxford University’s objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright © 2011 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The dynamic brain : an exploration of neuronal variability and its functional significance /

edited by Mingzhou Ding, Dennis L. Glanzman.

p.; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-19-539379-8

1. Neural circuitry. 2. Neural networks (Neuroibology) 3. Evoked potentials (Electrophysiology)

4. Variability (Psychometrics) I. Ding, Mingzhou. II. Glanzman, Dennis.

[DNLM: 1. Neurons—physiology. 2. Brain—physiology. 3. Models, Neurological. 4. Nerve Net—physiology.

WL 102.5 D9966 2011]

QP363.3.D955 2011

612.8′2–dc22

2010011278

ISBN-13 9780195393798

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2336402-250522204409-e1f17f74/75/The-Dynamic-Brain-An-Exploration-Of-Neuronal-Variability-And-Its-Functional-Significance-1st-Edition-Mingzhou-Ding-Phd-9-2048.jpg)

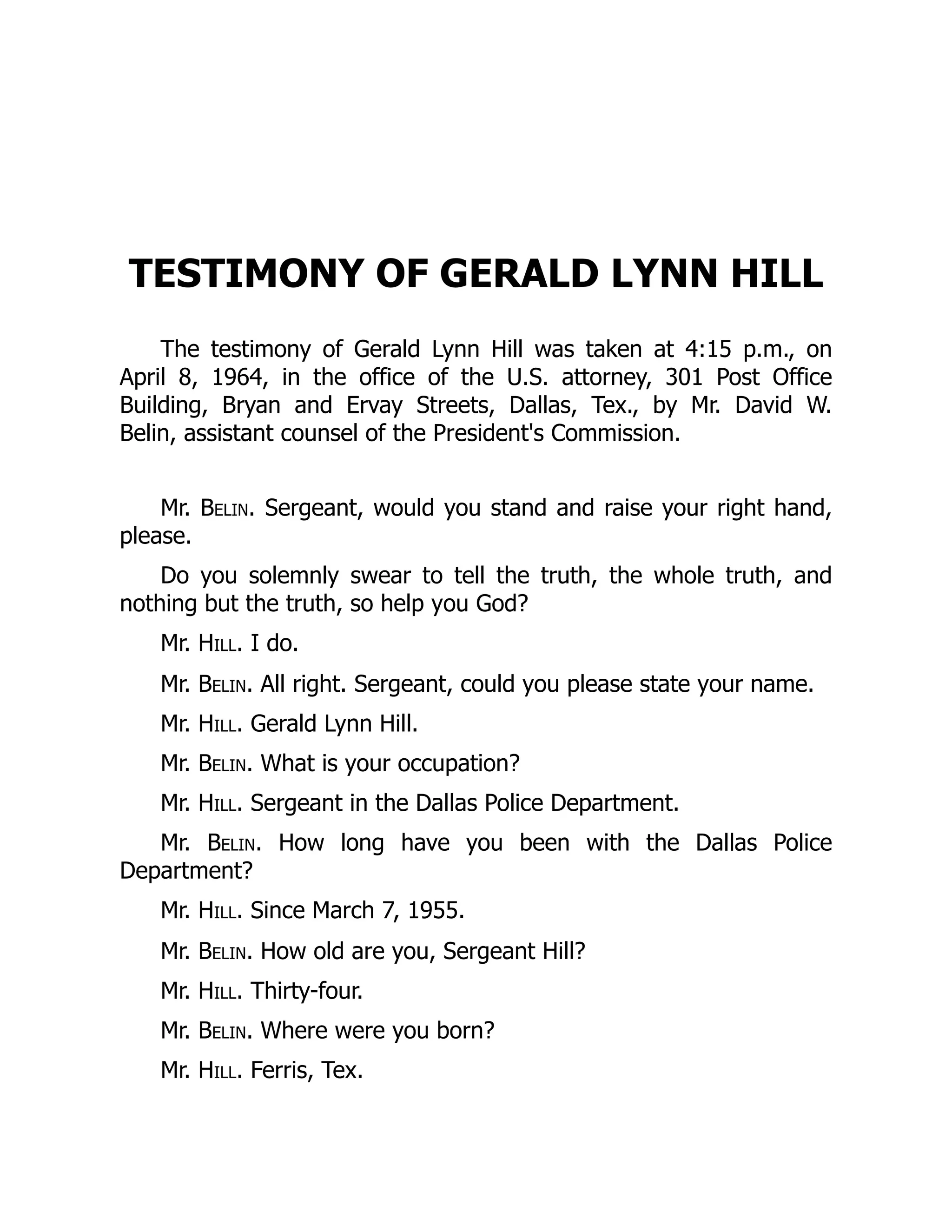

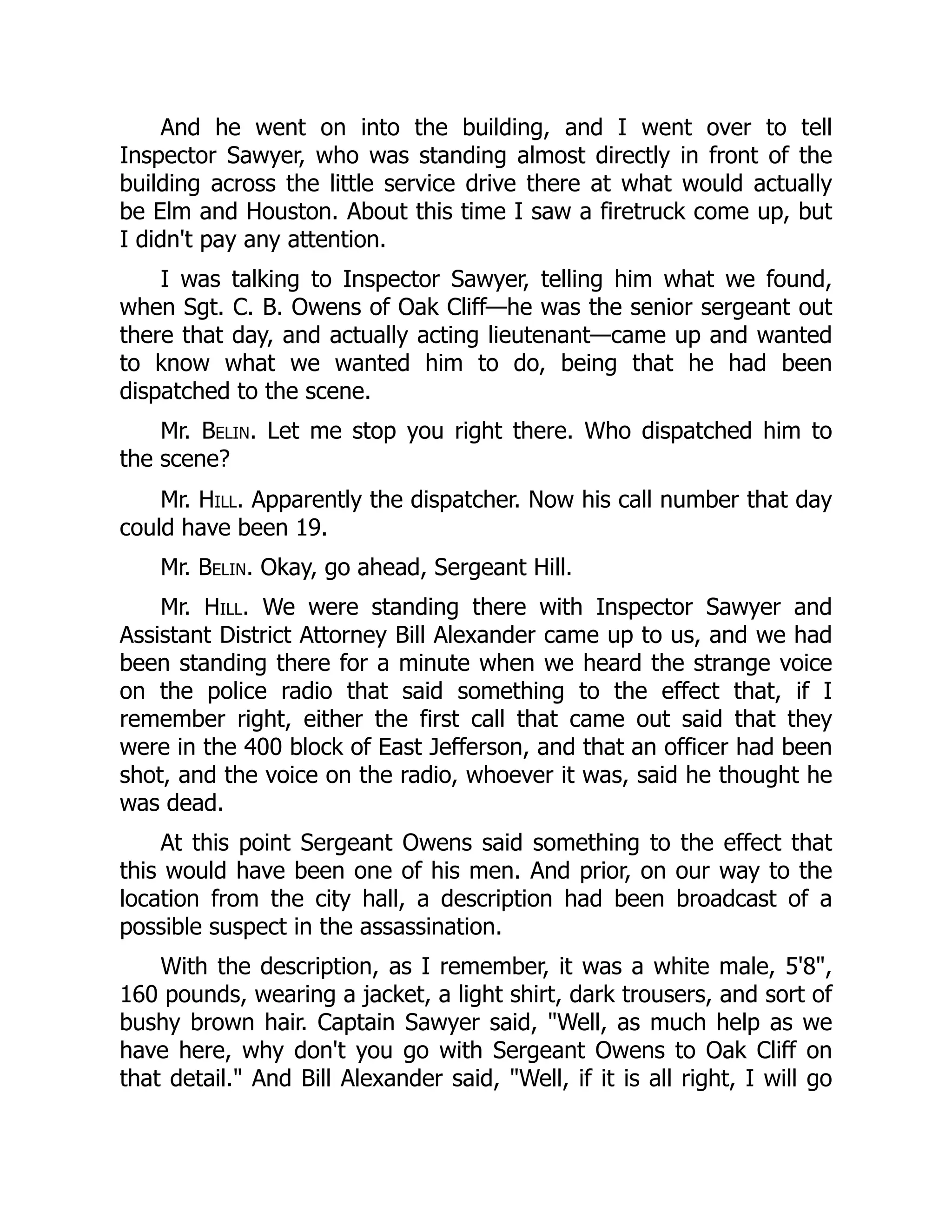

![1: A MIXED-FILTER ALGORITHM 5

equation relates the observed data to the cognitive state process. The data

we observe in the learning experiment are the neural spiking activity and the

continuous and binary responses. Our objective is to characterize learning

by estimating the cognitive state process using simultaneously all three types

of data.

To develop our model we extend the work in (Precau et al, 2008; Precau

et al., 2009) and consider a learning experiment consisting of K trials in which

on each trial, a continuous reaction time, neural spiking activity, and a binary

response measurement of performance are recorded. Let Zk

and Mk

be respec-

tively the values of the continuous and binary measurements on trial k for

k = 1…., K. We assume that the cognitive state model is the first-order autore-

gressive process:

X X V

k k

X k

V

V

+

−1

(1)

where r ∈( , )

0 1

, represents a forgetting factor, g is a learning rate, and the Vk

’s

are independent, zero mean, Gaussian random variables with variance. s2 v.

Let X X XK

[ , , ]

1 be the unobserved cognitive state process for the entire

experiment.

For the purpose of exposition, we assume that the continuous measure-

ments are reaction times and that the observation model for the reaction times

is given by

Z hX W

h

k k

hX

h

h k

W

W (2)

where Zk

is the logarithm of the reaction time on the Kth trial, and the Wk

W

W ’s

are independent zero mean Gaussian random variables with variance s2

w .

We assume that h < 0 to insure that on average, as the cognitive state Xk

increaseswithlearning,thenthereactiontimedecreases.Welet Z Z ZK

[ , , ]

1

be the reaction times on all K trials.

We assume that the observation model for the binary responses, the Mk ‘s

obey a Bernoulli probability model

P p p

k

pm

k

m

(1 )1

( )

M X x

k k

X k

= |

m

m = x − −

(3)

where m = 1 if the response is correct and 0 if the response is incorrect. We

take pk to be the probability of a correct response on trial k , defined in terms

of the unobserved cognitive state process xk as

pk =

( )

xk

+

+ ( )

xk

+

exp

e p

+

+

1 (4)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2336402-250522204409-e1f17f74/75/The-Dynamic-Brain-An-Exploration-Of-Neuronal-Variability-And-Its-Functional-Significance-1st-Edition-Mingzhou-Ding-Phd-28-2048.jpg)

![6 THE DYNAMIC BRAIN

Formulation of pk as a logistic function of the cognitive state process (4)

ensures that the probability of a correct response on each trial is constrained to

lie between 0 and 1, and that as the cognitive state increases, the probability

of a correct responses approaches 1.

Assume that each of the K trials lasts T seconds. Divide each trial into

J

T

=

Δ

bins of width Δ so that there is at most one spike per bin. Let Nk j = 1

if there is a spike on trial k in bin j and 0 otherwise for j T and

k K

, , . Let N N N

k k

N k J

, , ]

,1 be the spikes recorded on trial k , and

N N N

k

k

[ , , ]

1 be the spikes observed from trial 1 to k . We assume that the

probability of a spike on trial k in bin j may be expressed as

P N n x N n N n N

j k j

k k

x k k

n k k

n k j j

k

( =

Nk j | =

Xk

, =

N , =

Nk , , = )

nk j

k

= (

j k

j

1

k

n , ,1 1

j j

j

k

1 j

l ,

, )

j

nk j

, k j

e

Δ

Δ

−l (5)

and thus the joint probability mass function of Nk on trial k is

P N n x

k

n k k

x

j

J

k j k j

( =

Nk | =

Xk

) =

=1

k

ex l

p og

∑ ( )

k j

j

⎛

⎝

⎛

⎛ ⎞

⎠

⎟

⎞

⎞

⎠

⎠

l

nk j

)

k j − Δ

(6)

where (6) follows from the likelihood of a point process (Brown et al., 2002).

We define the conditional intensity function lk j as

logl y b

k j k

s

S

s k j s

g n

=1

, .

bs k j s

n

y k

gx

+ +

gxk

gx ∑b

b

∑b

b

(7)

The state model (1) provides a stochastic continuity constraint (Kitagawa and

Gersch, 1998) so that the current cognitive state, reaction time (2), probability of a

correct response (4), and the conditional intensity function (7) all depend on the

prior cognitive state. In this way, the state–space model provides a simple, plausi-

ble framework for relating performance on successive trials of the experiment.

We denote all of our observations at trial k as Y M N Z

k k

Y M

Y k k

Z

( ,Nk ). Because

X is unobservable, and because q ( )

g r s a y

r a

a s m h

h

s

s

a s is a set of

unknown parameters, we use the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm to

estimate them by maximum likelihood (Smith et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2005;

Smith and Brown, 2003; Fahrmeir et al., 2001; Percau et al., 2009). The EM

algorithm is a well-known procedure for performing maximum likelihood

estimation when there is an unobservable process or missing observations.

The EM algorithm has been used to estimate state–space models from point

process and binary observations with linear Gaussian state processes (Dempster

et al., 1977). The current EM algorithm combines features of the ones in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2336402-250522204409-e1f17f74/75/The-Dynamic-Brain-An-Exploration-Of-Neuronal-Variability-And-Its-Functional-Significance-1st-Edition-Mingzhou-Ding-Phd-29-2048.jpg)

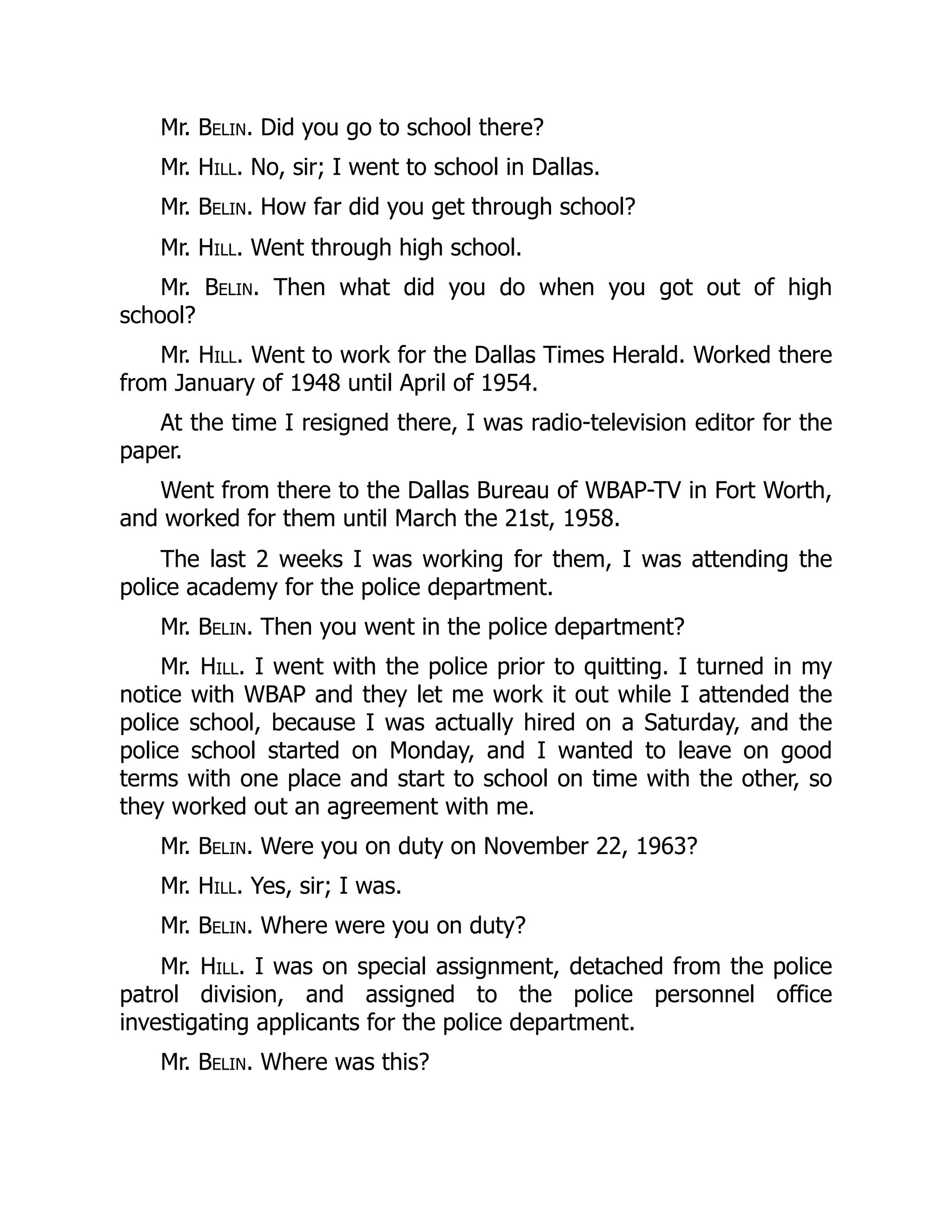

![1: A MIXED-FILTER ALGORITHM 7

(Shumway and Stoffer, 1982; Smith et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2005).The key

technical point that allows implementation of this algorithm is the combined

filter algorithm in (8)-(12). Its derivation is given in Appendix A.

Discrete-Time Recursive Estimation Algorithms

In this section, we develop a recursive, causal estimation algorithm to estimate

the state at trial k, Xk , given the observations up to and including time k ,

Y y

k k

y . Define

x E Y y

k

k

k k

y

| [ |

Xk ]

′ ′

k

=

sk k k

k k

Xk y

|

2

| =

k

Y

′

′ ′

k

⎡

⎣

⎡

⎡ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

var

as well as pk k

| and lk k j

, |

j by (4) and (7), respectively, with with xk replaced

by xk k

| .

In order to derive closed form expressions, we develop a Gaussian approx-

imation to the posterior, and as such, assume that the posterior distribution on

X at time k given Y y

k k

y is the Gaussian density with mean xk k

| and vari-

ance sk k

|

2

. Using the Chapman-Kolmogorov equations (25) with the Gaussian

approximation to the posterior density, i.e. Xk given yk

, we obtain the follow-

ing recursive filter algorithm:

One Step P

e rediction

x x

k k k

| 1

k 1| 1

k

1 −

+

g r

+ (8)

One Step P

e rediction Varianc

V

V e

s r s s

k k k V

| 1

k

2 2

r | 1

2 2

s

r k − (9)

Gain Coefficien

e t

C

h

k

k

k W

=

| 1

k

2

2

| 1

k

2 2

s

s s

k| 1

k

2

(10)

Posterior Mode

x C h

C

k k k h

j

J

k W

| |

x

k k |

W k

( )

p k

|

p

k

m k

= +

x k

|

xk ( )

z h

k

z k|k + (m

mk

m

⎡

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

+

−

=

∑C

1 k k k k

1 Ck h

+ k

z

k k

2

1

2

)

hx +

hxk k

k k

s g

g

g j j j

( )

nk j k j j

j

j k | ,

k

⎡

⎣

⎡

⎡ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

l Δ

(11)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2336402-250522204409-e1f17f74/75/The-Dynamic-Brain-An-Exploration-Of-Neuronal-Variability-And-Its-Functional-Significance-1st-Edition-Mingzhou-Ding-Phd-30-2048.jpg)

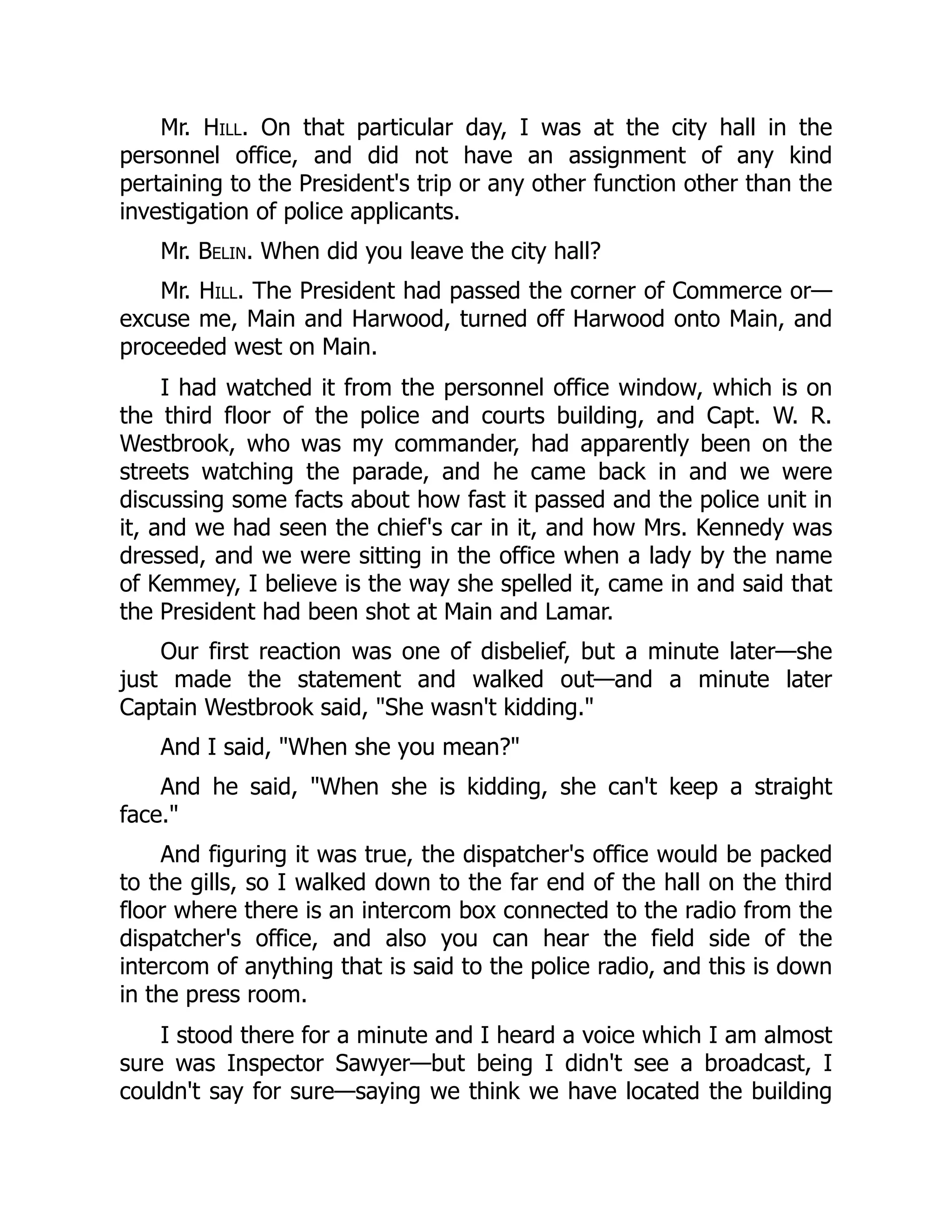

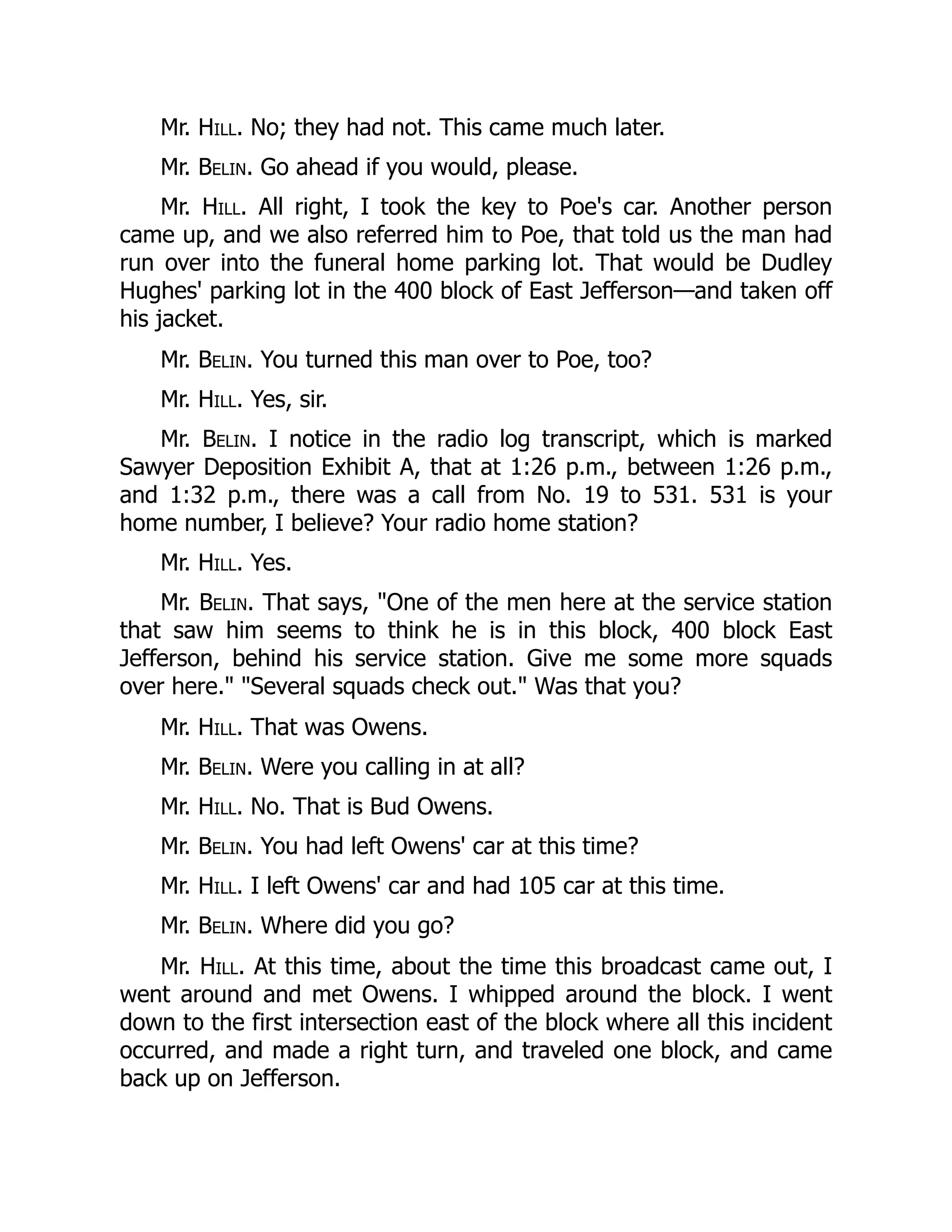

![1: A MIXED-FILTER ALGORITHM 9

E-STEP I: NONLINEAR RECURSIVE FILTER

The nonlinear recursive filter is given in (8) through (12).

E-STEP II: FIXED INTERVAL SMOOTHING (FIS) ALGORITHM

Given the sequence of posterior mode estimates xk k

| and the variance sk k

|

2

, we

use the fixed interval smoothing algorithm [20, 3] to compute xk K

| and sk K

|

2

Ak

k k

k k

r

s

s

|

2

1|

2 (13)

x x A

k k k

| |

x

K k + A ( )

x

k

x K k

x k

| 1|

−

xk

x K

1|K k

x

1|K

1| (14)

s s

k K k k k

|

2

|

2 2

A

+ k

A2

A ( )

s

k

s K k

s k

|

2

1|

2

−

s

s2

K k

s

1| (15)

for k K 1

K , ,1 with initial conditions xK K

| and sK K

|

2

computed from the last

step in (8) through (12).

E-STEP III: STATE–SPACE COVARIANCE ALGORITHM

The conditional covariance, sk K

, |

k′ , can be computed from the state–space

covariance algorithm and is given for 1 ≤ ′ ≤

k k

≤ K by

s s

k K k k k K

A

, |

k , |

′ (16)

Thus the covariance terms required for the E-step are

W x x

k

W

W k K k

x K

, 1

k , 1

k | |

x

K k

x 1|

k

1 k + (17)

W x

k k

W

W K k

x K

|

2

|

2

(18)

M-Step

The M-step requires maximization of the expected log likelihood given the

observed data. Appendix B gives the computations that lead to the following

approximate update equations:

g

r

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎦

⎥

⎥

=

=

−

=

∑

∑ ∑

K x

∑

W

∑

x

k K

−

k

K

−

k

K

k

W

W

k

K

k K

1

1

1

1

|

|

|

k

k

K

k k

k

K

Wk

=

=

∑

∑

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎦

⎥

⎥

1

1

,

(19)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2336402-250522204409-e1f17f74/75/The-Dynamic-Brain-An-Exploration-Of-Neuronal-Variability-And-Its-Functional-Significance-1st-Edition-Mingzhou-Ding-Phd-32-2048.jpg)

![1: A MIXED-FILTER ALGORITHM 19

To evaluate xk k

| −1 and sk k

| ,

−1

2

we note that they follow in a straightforward

manner:

x X Y y x

k

k k

y k

| |

X Y y x

k k k

|Y

X Y

Xk |

⎡

⎣ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤ = +

1

k

y −

k

1

k−

k

E r

+ (27)

sk| 1

k

2

= var

var ( )

k k

Y y

k

k

Yk 1

|

k

X

X −

k

(28)

= ( )

| = 1

Y

| y

k k

1

y

1

(29)

= 2

1| 1

2 2

r s

2

s

k k

1| V

−

k

1| + (30)

Substituting all these equations together, then we have that the posterior

density can be expressed as

f

X

f

f

k Y

k

k

|

2

| 1

k

2

1

{

( )

x x

k k

x | 1

k

2

[ (

k

p 1 )

pk ]

( )

xk

x k

| yk

[ (

pk

p 1 +

−

l

m

|

2

{

( )

k k| 1

k

2

−

{ + m g

s

lo

l

l g(1 )

− pk

− + ( )

∑

( )

2

}

2

2

=1

(

h

− −

n

∑

∑

W j

J

k j

, k j

,

s

l

)−

log Δ

⇒ ( )

− + −

log

l g

f (

C y m p

X

f

f

k Y

(

k

k

k g

og k

|

|

2

| 1

−

k

2

= (

C )

( )

x x

−

k k

x | 1

−

k

2

[ (

k

p 1

s

) ]

)

) (1 )

1

−

(1

+ log pk

(31)

− + ( )

∑

( )

2

2

2

=1

(

h

− −

n

∑

∑

W j

J

k j

, k j

,

s

l

)−

log Δ (32)

Now we can compute the maximum-a-posteriori estimate of xk and its

associated variance estimate. To do this, we compute the first and second deriv-

atives of the log posterior density with respect to xk , which are respectively

0 = =

( ) ( )

| |

| 1

2 2

∂ ( )

|

∂

− + +

log f

|

(

x

h z

( h

X

f

f

k Y

(

k k| W

s s

h

h( )

+∑

j

J

j j

g

∑

∑

=1

j

( )

−

k j k j

n j k

l Δ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2336402-250522204409-e1f17f74/75/The-Dynamic-Brain-An-Exploration-Of-Neuronal-Variability-And-Its-Functional-Significance-1st-Edition-Mingzhou-Ding-Phd-42-2048.jpg)

![1: A MIXED-FILTER ALGORITHM 21

Note that the expected log-likelihood

Q { }

Y y

X Y

K K

y

f

X

f

f K YK

f |

|

f K K ( )

K K

|

K

;

YK

Y

|

xK

; has linear terms inE Yk k

y

[ |

Xk = ]

yk

y

along with quadratic terms involving

W

k j

W

W ,

E{ }

X X

k j

X K K

|Y y

K K

y except for a

couple of terms, including E Y

gx k k

y

[ |

e

gxk

= ]

yk

y . We note that if ∼

X N ( )

m s2

then

its moment generating function M t E ext

( )

t [ ]

ext

is given by

M t e

ut t

( )

t = .

e

1

2

2 2

t

+ s

(36)

With this, we have

Q C X X y

Z

K

k

K

V

K K

y

W

k

( )

y

1

2

( )

X X

k k

X | =

YK

1

2

(

=1

2

2

2

q

s

s

a

X

⎡

⎣ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

−

Z

(

− −

∑

∑ E

E hX

h

h Y y

k

k k

y

) |

2

⎡

⎣

⎡

⎡ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

+ ( )

+ − ( )

+

⎡

⎣

⎡

⎡ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

∑

k

K

k ( ) ⎡

⎣

⎡

⎡ k k

m

∑ k ( Y y

=1

+ |

)

) =

+

+

+ +

+

E l g(

( +

+

(37)

+

⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

⎟

⎞

⎞

⎠

⎠

−

∑ ∑

⎛

⎛

⎛

∑

k

K

s

S

s k j s

−

k

s

S

s k

∑ n

s

g n

=1

|

⎝

⎝

⎝

⎝

j

⎝

⎜

⎝

⎝ =1

,

=1

,

b

∑

∑b

∑

+ +

+ ∑

+

+

y b

+ + ∑

∑

k

gX

E e p j

j s

K K

y

−

⎛

⎝

⎜

⎛

⎛

⎝

⎝

⎞

⎠

⎟

⎞

⎞

⎠

⎠

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

Δ | =

K

YK

(38)

= ( )

1

2

2 2 2

2

=1

| 1,

2

1|

2

1

C y

( W 2 1

W x

2

2

W

K

V k

K

k k

W

W 2 k k K k

W

W

W

− 2 W 1 +

2

∑W

∑W

W 1 k −

s

|

k

x 2

2

2 2

2

2 r

1|

k

x K +

1|

xk

x K

−

k

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

− +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

∑

1

2

( ) 2( )

2

=1

2

|

2

s

a

−

) 2(

2

W k

K

k

) (

) ( k K

| k

− −

) 2(

2

) 2( hx h W

2

k

+ ( )

+ − ( )

+

⎡

⎣

⎡

⎡ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

∑

k

K

k ( ) ⎡

⎣

⎡

⎡ K K

m

∑ k ( Y y

=1

+ |

)

) =

+

+

+ +

+

E l g(

( +

+ (39)

+

⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

⎟

⎞

⎞

⎠

⎠

− + +

∑ ∑

⎛

⎛

⎛

k

K

s

S

s k j s

−

k K

∑ n

s

g g

=1

|

⎝

⎝

⎝

⎝

j

⎝

⎜

⎝

⎝ =1

,

|

k

|K

2

1

2

b

∑

∑b

∑

+ +

+ ∑

+

+

y s

+ +

k

gx | +

K

Δe p 2

2

=1

,

+

⎛

⎝

⎜

⎛

⎛

⎝

⎝

⎞

⎠

⎟

⎞

⎞

⎠

⎠

∑

s

S

s k j s

−

n

b

∑

∑

(40)

where in going from (38) to (40), we have used the (36).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2336402-250522204409-e1f17f74/75/The-Dynamic-Brain-An-Exploration-Of-Neuronal-Variability-And-Its-Functional-Significance-1st-Edition-Mingzhou-Ding-Phd-44-2048.jpg)

![22 THE DYNAMIC BRAIN

We now rely upon the Taylor series approximation around xk K

|

E X Y

k

K K

K

[ ( )| = ]

yK

( )

xk

1

2

( )

xk K

| |

k

)

K

2

2

|

r

X Y

k

( )| ]

yK

y s r

K

k

2

+ ′′

Let us now consider the conditional expectation term involves

log( )

1 (

exp )

+

(

exp +

r

m m h

1( ) =

( )

m h

1 ( )

= ,

x

p

k

k

∂ ( )

m h

( )

xk

+

1 +

∂ +

m

(

g(1

1 exp

(41)

r

h m h

2( ) =

( )

m h

1 ( )

=

x (m h

x

x p

k (m h

(m h

k

k k

p

∂ ( )

m h

( )

xk

+

1 +

∂ +

m

(

g(1

1 e p

(42)

Note from before that

′ −

r1

2

( ) = (

h 1 )

− = (

h )

h p

) = (

h p

) =

) = h k

) (p

) = (

h k

⇒ ′′

r h h

1 ( ) = [

h (1 ) 2 (1 )]

−

p − p p

−

(1

k k k

( ) p

p

( ) k k

( p

(1

= (1 )(1 2 )

2

p

(1 k

( p

(1 −

)(1

p

Thus we have that

f m Y y

k

K

k

K K

y

f

f

=1

|

m

∂

∂

( )

xk

x K

|

m h

+ ( )

Xk

X

1 ( )

⎡

⎣ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

⎧

⎨

⎧

⎧

∑m

m E l g(

⎩

⎩

⎨

⎨

⎨

⎨

⎫

⎬

⎫

⎫

⎭

⎬

⎬ (43)

= ∑

k

K

k k

K K

m X

−

∑

∑ k YK

=1

( )| = ]

K

y

E (44)

k

K

k k K k K

m p

k p p

k

=1

| |

K k

2 2

| |

K k

p

K |

1

2

(1 )(1

)(1 2 )

k K

p |

∑m −

p −

p )(1

s h

K

|

k

2

(45)

Let us now consider r2( ) x

) = p

k

) x

) = k . Note from (42) that

′ ′

r r

2 1

r

( ) [ ( )]

k

)

= ( ) ( )

) x

k

(

( k

′( )

)

x

( k

(x

(

(](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2336402-250522204409-e1f17f74/75/The-Dynamic-Brain-An-Exploration-Of-Neuronal-Variability-And-Its-Functional-Significance-1st-Edition-Mingzhou-Ding-Phd-45-2048.jpg)

![1: A MIXED-FILTER ALGORITHM 23

⇒ ′′ ′ ′ ′′

r2( ) = (

′

r ) (

+ ′

r1 ) (

+ ′′

r

+ 1

r )

x

(

r + x

k

) (

1

r x

(

r1

r k )+

+ k

= 2 ( ) ( )

1 1

(

′ + ′′

r r

( )

1( +

)+ k

)

)

)

)

)+

= 2 (1 ) (1 )(1 2 )

2

h (1 )

p (1 p )(1 2

k k

( p

(

(1 k )( 2

)(1 2

)

) − p )(1

= (1 )

(1 )

(1

(

(

(1 )

)[ ]

2 (1 2 )

2 p

(1 2 k

( p

(1 2

2

2

Thus we have that

f m Y y

k

K

k

K K

y

f

f

=1

|

h

∂

∂

( )

xk

x K

|

m h

+ ( )

xk

x

1 ( )

m h

1 +

⎡

⎣

⎡

⎡ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

⎧

⎨

⎧

⎧

∑m

m E l g(1

1

⎩

⎩

⎨

⎨

⎨

⎨

⎫

⎬

⎫

⎫

⎭

⎬

⎬ (46)

= [ ( )| = ]

=1

| 2

[

k

K

k k (

2

[ K K

)| y

∑ E r (47)

k

K

k k K k K k K k

m x

k x p

K pk xk

=1

| |

K k

xk | |

K k

2

| |

K k

K | |

K

K

1

2

(1 ) 2 (1 2 )

K

p |

k

p

∑m − −

x p +

2

− K

p |

k

p )

s h

K

|

k

2

h

⎡

⎡

⎣ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤ (48)

Thus we differentiate to find a local minimum

0 = =

1

2

=1

| 1|

∂

∂

− − + +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

∑

Q

x x

| +

V k

K

k|

| K

1|

g s

r

+

+

0 = =

1

2

=1

, | 1

∂

∂

− − +

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

∑ −

Q

W x

+ W

V k

K

k k

1,

−1

W

W 1 k K

1| k

W

W

r s

g r

+

|

xk K

1|

1|

−

0 = =

1

2

=1

|

∂

∂

− −

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

∑

Q

z h

+ x

W k

K

k k

h

+ x K

a s

a

∑

∑

0 = =

1

( )

2

=1

|

∂

∂

− − +

) |

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

∑

Q

h

) hW

W k

K

k

)x

)

) K k

+ hW

W

s

0 = =

1

]

( ) 2( )

2 2

2[ 2

2

=1

2

|

2

∂

∂

− −

)

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

⎤

∑

Q

(

K 2

+

2

∑ z h

)

− ) x h

+

| W

W W

[

W

k

K

k

) 2(z k K

|

|

| k

W

W

s s

2[

2

2[

W 2[

s (

∑(

+

2

∑

W a

⎦

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

⎦

⎦

0 = =

1

2

(1 )(1 2 )

=1

| |

2

2 2

| |

( |

∂

∂

− −

)(1

∑

Q

m p

−

∑

∑ p p

(1

| (1−

k

K

k k

p

2

K k

p (

(1 K )(1 2

m

s h

|

2

K (49)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2336402-250522204409-e1f17f74/75/The-Dynamic-Brain-An-Exploration-Of-Neuronal-Variability-And-Its-Functional-Significance-1st-Edition-Mingzhou-Ding-Phd-46-2048.jpg)

![1: A MIXED-FILTER ALGORITHM 25

C Newton Algorithms to Solve Fixed Point Equations

Newton Algorithm for the Posterior Update

We note that xk k

| as defined in (11) is the root of the function r :

r( ) = (

hs )

| |

) |

2

|

C h p

W k

(m k k

|

( )

a |

h −

(

hs m

(m

⎡

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

+ ⎡

⎣ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

∑

j

J

W j j j

C g

⎡

⎣

⎡

⎡

∑ k W

=1

2

j | ,

( )

k j k j j

j k | ,

k

l

⎡g

⎡

⎡

⎡

W

2

( −

k j

n Δ

⇒ ′

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎣

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

∑

r s h l

− + ∑

( ) )

|

2 2

⎡

⎢

⎡

⎡

h | |

(

=1

2

, |

C

−

) 1

− p −

( g

∑

∑

∑

k W

s k|

| k

|

j

J

k j

, k j

, Δ

Either the previous state estimate, xk k−

k

1| 1 , or the one-step prediction estimate,

xk| 1

k , can provide a reliable starting guess.

Binary Parameters

In this section we develop derivatives of the functions f3

f

f and f4

f

f for the

purpose of enabling a Newton-like algorithm to find the fixed point pertaining

to (49)–(50). Define:

f m p p p

k

K

k k

p K

k k k

p

3

f

f

=1

|

2 2

1

2

(1 )(

)(1 2 )

pk

∑m

m − p − p

s2

f m x x p p x

k

K

k k

x K k

p k K k k

p k K

f

f

=1

| |

x

K k

x |

2

|

1

2

(1 )

) 2 (1 2 )

pk

∑m

m x p +

− p

p ) 2 −

⎡

⎣ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

s h

2

h

We arrive at the Jacobian:

∂

∂

{ } + −

⎡

⎣

⎡

⎡ ⎤

⎦

⎤

⎤

⎡

⎣

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

∑

m

p

} ∑ + −

⎡

⎣

⎡

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

s h

k

K

K

k

=1

|

2 2 2

(

p

−∑

∑ k 1 )

− pk

p 1

1

2

(1 2 )

pk 2 (

pk

p 1 )

p

− k

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦

∂

∂

{ }

+ + −

∑

h

h

p

} ∑

x + −

h x

k

K

k K k

x K

=1

| |

+ s

K k

2 2 2

| |

+

K k

+s2

(

p

−∑

∑ k 1 )

− pk

p

1

2

(1 2 )

pk [1 2 (

2

2 1 )]

| (1

(1

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎡

⎡

⎣

⎣

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎤

⎤

⎦

⎦](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2336402-250522204409-e1f17f74/75/The-Dynamic-Brain-An-Exploration-Of-Neuronal-Variability-And-Its-Functional-Significance-1st-Edition-Mingzhou-Ding-Phd-48-2048.jpg)