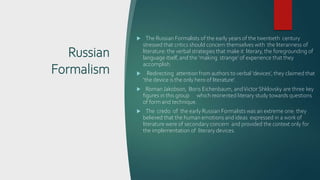

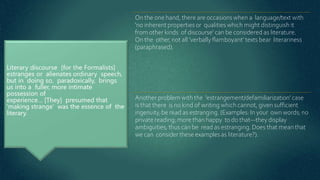

Terry Eagleton explores various definitions of literature, emphasizing the complexities of what constitutes literary works and the influence of language and form. He highlights the weaknesses in each definition, arguing that literature cannot be objectively defined and is shaped by social ideologies and value judgments. Ultimately, Eagleton suggests that understanding literature requires an analysis that goes beyond mere definitions to consider its cultural roles and implications.