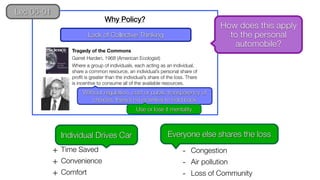

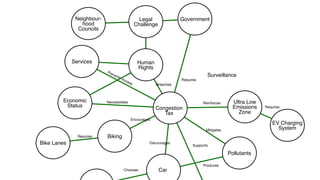

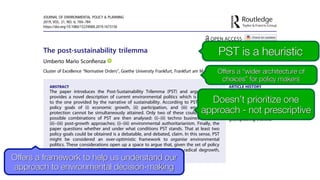

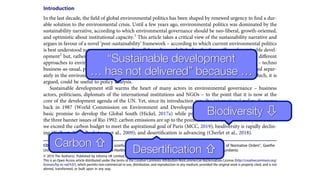

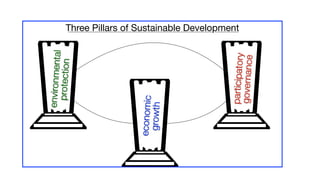

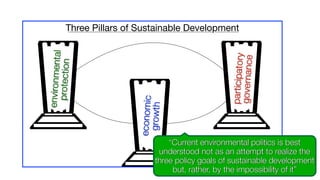

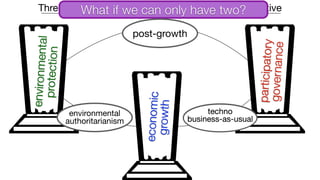

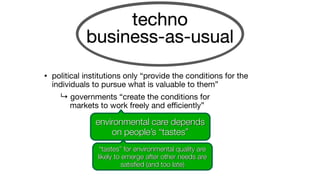

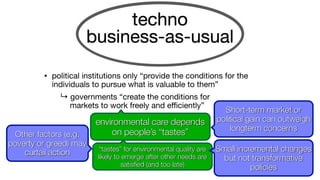

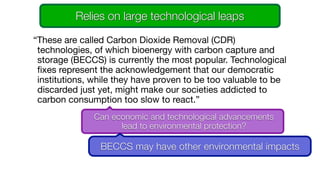

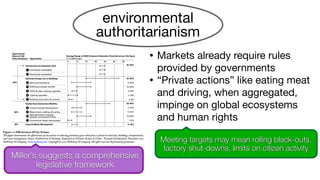

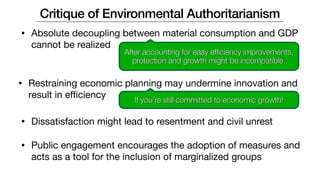

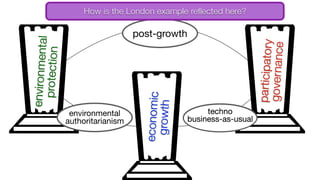

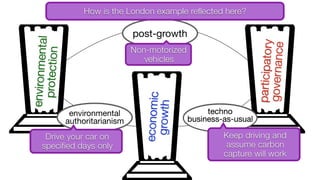

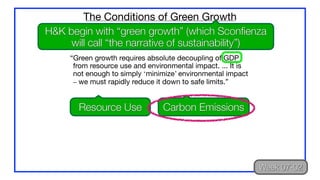

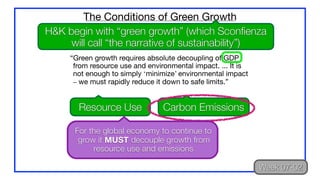

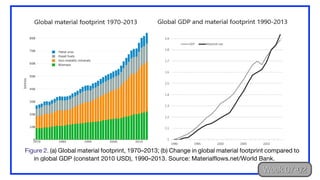

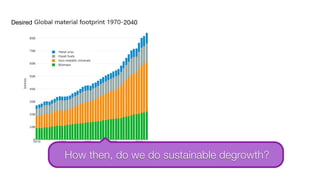

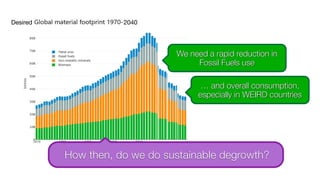

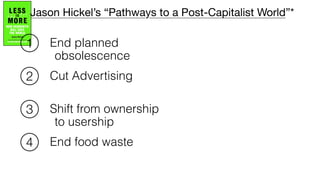

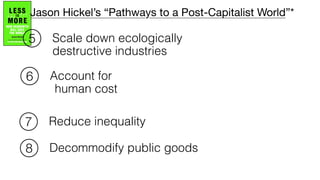

The document introduces the Post-Sustainability Trilemma (PST) framework for understanding environmental politics. PST argues that the three policy goals of economic growth, public participation, and environmental protection cannot be achieved simultaneously. Only two goals can be attained at once. The three possible combinations are: 1) economic growth and participation through a techno-business as usual approach, 2) participation and environmental protection through post-growth approaches, and 3) economic growth and environmental protection through environmental authoritarianism. However, the document questions whether PST accurately describes being able to attain only two goals, as this is debatable. Considering the policy options in PST could lead to more radical conclusions around issues like degrowth, decentralization,