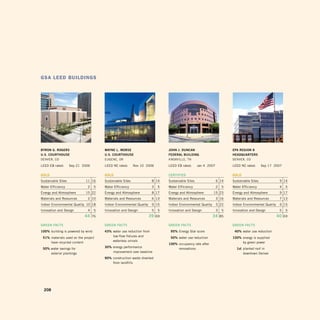

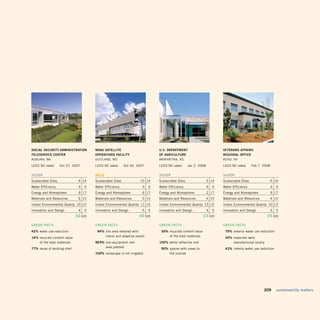

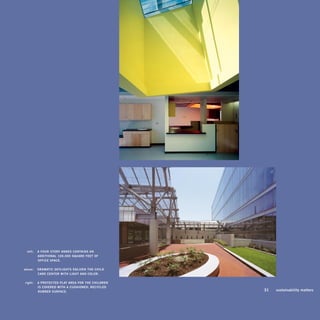

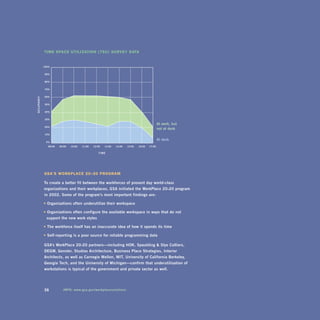

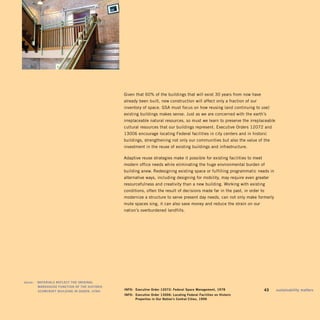

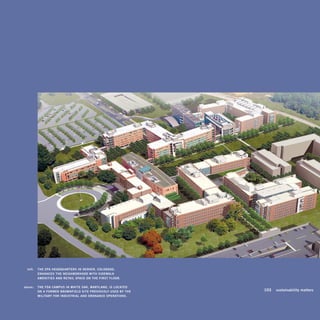

The U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) emphasizes sustainability as crucial for high-quality federal workplaces, highlighting initiatives for energy efficiency and environmentally responsible building practices. The document outlines GSA's ongoing efforts to integrate sustainable design principles across its projects, including case studies that showcase successful implementations. It underscores a commitment to reducing the federal government's environmental footprint and leading by example in the building industry.

![yearly (not absent in the summer) and weekly (using solar heat every day)

water-heating loads. Typical best practice, or that which most effectively

minimizes life-cycle cost, is a system design that meets 100% of the load on

the sunniest day of the year (and thus approximately 70% of the annual load).

solar cells/photovoltaics (pv)

Solar cells, also known as photovoltaics (PV), convert sunlight directly into

electricity, using semiconducting materials similar to those used in computer

chips. Because thin film solar cells use layers of semiconductor materials only

a few micrometers thick, it is possible for solar cells to be bonded to roofing

materials, offering the same increased protection and durability.

Cost-effective renewable opportunities depend on a number of factors,

including the utility rate and rate structure, available incentives, and whether

“i’d put my money on the state renewable portfolio standard includes a solar set-aside (thus creating

the sun and solar energy. a solar REC [Renewable Energy Credit] market). A potential site must also

what a source of power! consult with its serving utility to determine if the electricity generated in

i hope we don’t wait ’til excess of local needs can be sold back to the utility at reasonable rates.

oil and coal run out before

we tackle that.” PV installations provide an extremely low maintenance, long-lived source of

ThoMas Edison power. The first commercial PV panel installed more than 50 years ago is

still producing power.

top: EvaCUaTEd TUbE CoLLECTors ConTain METaL

pLaTEs To CapTUrE and TransfEr soLar

EnErgy for hEaTing WaTEr.

above: CrysTaLLinE phoTovoLTaiC panELs arE onE

of Many opTions avaiLabLE for TUrning

sUnLighT inTo ELECTriCiTy. 87 sustainability matters](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sustainabilitymatters-101210132737-phpapp01/85/Sustainability-Matters-93-320.jpg)

![Site and Water

SuStainable Site DeSign

Site selection and designing for “place” is key to providing new buildings that

are iconic, respectful of taxpayer’s dollars and environmentally responsible.

However, because the location of building sites are often set and not easily

changed, many government projects overlook the opportunities for including

sustainable site design objectives. Ignoring the site, its use and response to

environmental factors, will affect building energy and water consumption,

comfort, and tenant satisfaction.

“these buildings will be here Site Selection

for hundreds of years—long

There are political and financial implications to consider in choosing a site as

after we [have] relocated the

well as customer requirements to address. GSA’s Site Selection Guide (2003)

last tenant, or written the

last report. they should be is a great resource that focuses on how the basic concepts of site section will

in the right location—that is affect the overall success of the project.

our overriding responsibility.”

As stated in the guide, “...site selection is a “life-cycle” decision that

GSA Site Selection Guide

recognizes the balance among the initial cost of the real estate, the overall

cost of executing the project, and the cost of operating the facility. It also

recognizes the benefit (or cost) to the local community and the environment.

While the initial cost may be a significant driver, all factors must be

considered in order to make the right decision.”

Transportation and Parking

Site selection decisions are multifaceted. Two of the most important, but

often overlooked criteria are access to public transportation and parking

availability. Removing vehicles from our highways benefits the community

and the health and well-being of commuters by improving air quality and

removing the stress of extended daily travel. Therefore, whenever possible,

left: The OklAhOmA CiTy FederAl BuildinG

emBrACeS iTS SiTe wiTh An urBAn PArk

OPeninG FrOm The BuildinG And A

COurTyArd ACCenTed wiTh TurF GrASS,

hArdSCAPe, And A wATer FeATure.

inFO: GSA Site Selection Guide – www.gsa.gov/siteselection 101 sustainability matters](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sustainabilitymatters-101210132737-phpapp01/85/Sustainability-Matters-107-320.jpg)

![Materials

Designers have traditionally focused on the core material characteristics—

function, aesthetics, availability and cost—and rightly so. They remain the

cornerstone of product selection; without them, inappropriate and costly

materials will prematurely be sent to the landfill as building occupants tire

of non-performing products. This perpetuates unnecessary consumption and

adds undue stress on available material and energy resources.

New thinking integrates sustainability issues into the decision-making

process. The basic list of questions is deceptively short but the answers

to each are extensive.

• Do I need to use it at all?

• Where did it come from?

• What is it made of?

• How was it made?

• How is it maintained?

• Is it safe?

• How much energy and water does it use?

• What happens to it at the end of its life?

“We believed that a noble material

• How do I know you’re telling me the truth?

[granite] was essential and that

the buildings should be of classic

By drilling down into the complexities, the questions begin to delve into

design and of the same scale.”

specifics. For example, “where did it come from” addresses the extraction,

arNOld W. BruNer, archiTecT,

processing, and manufacturing for finished products as well as their

clevelaNd Federal BuildiNg

component parts. Were they locally or regionally sourced or have they

[MeTzeNBauM cOurThOuSe].c.1910

accumulated embodied energy by traveling long distances? For complicated

products, the research can be exhaustive; even simple products, such as

certain types of glass, require finding out where the sand came from.

142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sustainabilitymatters-101210132737-phpapp01/85/Sustainability-Matters-148-320.jpg)