Sufism, or Islamic mysticism, is concerned with direct personal experience of and communion with God through subjective experience. Early Sufis sought to devote themselves to spirituality and moved away from politicized cities. Key Sufi practices included asceticism, prayer, recitation of the Quran, and contemplation. Sufism is primarily learned through serving a teacher for many years. Central Sufi doctrines include the unity of all phenomena as manifestations of a single divine reality, and the concept of the "Perfect Man" who acts as a channel of God's grace. The goal of Sufism is realization of the divine unity by letting go of notions of duality and the individual self

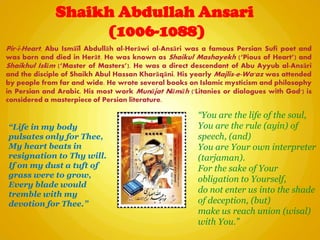

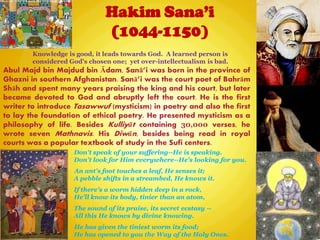

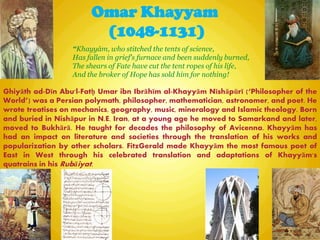

![…Sufi Orders

Yasāwi [founder: Khwāja Ahmed Yesevi] in modern Kazhākistan was one of the earliest

orders. Kubrāwiā [f: Najmedddin Kubrā] originated in C. Asia. The best known of silsilās in

S. Asia/India are: (1) Chishtiā (2) Naqshbandiā (3) Qādiriā and (4) Suhrāwardiā. One

particular order that is unique in claiming spiritual lineage through the Caliph Abu Bakr, who

was generally seen as more of a political leader than a spiritual leader, is the Naqshbandiā.

The North African Abu'l-Hasan al-Shādhili (d 1258) was the founder of the Shadhiliā.

The Rifa`iā was definitely an order by 1320, when Ibn Battutā gave us his description of its

rituals. The Khalwatiā [f. Umar al-Khalwati, an Azerbaijani Sufi]. While its Indian Subcontinent

branches did not survive into modern times, it later spread into the Ottoman Empire and

became influential there during the 16th cent. It crystallized into a Tariqā between 1300 and

1450. The founder of the Shattariā was `Abdullāh al-Shattār (d. 1428). Currently, orders

worldwide are: Bā ‗Alāwiyyā, Khalwati, Nimātullahi, Oveyssi, Qādiriā Boutshishiā, Tijāni,

Qalandariā, Sarwari Qādriā, Shadhliā, Ashrafiā, Jerrāhi, Bektāshi, Mevlevi, Alians etc.

Qadiriās [f: Abdul-Qādir Gilāni (1077-1166)] one of the oldest Sufi Tariqās. And the most

widespread Sufi order. They and their many offshoots, are found in the Arabic-speaking world,

Afghānistān, S. India, Banglādesh, Pākistān, Turkey, the Balkans, China, Indonesia, India,

Israel, and much of the E&W Africa, like Morocco. They strongly adhere to the fundamentals of

Islām. Their leadership is not centralized, and own interpretations and practices are permitted.

A rose of green and white cloth, with a six-pointed star in the middle, is traditionally worn in the

cap of Qādiri darveshes. Teachings emphasize the struggle against the desires of the ego. It is

described as "the greater struggle" (Jihād). Names of God are prescribed as Wazifās (chants)

for repetition by initiates (Zikr) in both loud and low voice. Though the Sunnā is the ultimate

source of religious guidance, Walis (saints) are God's chosen spiritual guides for the people.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sufismppt-210817051348/85/Sufism-ppt-12-320.jpg)

![…Sufi Orders

The Chishtiās [founded in Chisht, near Herat about 930 by Abu Ishaq Shami] are known

for their emphasis on love, tolerance and openness and for the welcome extended to seekers

who belong to other religions. They flourish in S. Asia and Afghanistan and have attracted

many westerners. Their insistence on otherworldliness has differentiated them from Sufi

orders that maintained close ties to rulers and courts and deferred to aristocratic patrons.

Chishtias follow five basic devotional practices. 1. Reciting the names of Allāh loudly,

sitting in the prescribed posture at prescribed times (Zikr-i Djahr) 2. Reciting the names of

Allāh silently (Zikr-i Khafī) 3. Regulating the breath (Pās-i Anfās) 4. Absorption in mystic

contemplation (Murāqāba) 5. 40 days of spiritual confinement in a lonely corner or cell for

prayer and contemplation (Chilla). Chishti practice is also notable for Samā'- evoking the

divine presence through song or listening to music or dancing with jingling anklets. The

Chishti, as well as some other Sufi orders, believe that music can help devotees forget self

in the love of Allāh. The music usually heard at Chishti shrines and festivals is Qawwāli,

invented by Amir Khusro, which is a representation of the inner sound.

Early Chishti shaikhs adopted concepts and doctrines outlined in two influential Sufi texts:

the ʿAwārif al-Maʿārif of Shaikh Shihāb al-Dīn Suhrawardī and the Kashf al-Maḥdjūb of

Hujwīrī. These texts are still read and respected today. Chishti also read collections of the

sayings, speeches, poems, and letters of the shaikhs called Malfūẓāt.

The most famous of the Chishti saints is Mu'īnuddīn Chishtī of Ajmer, India, others being:

Qutab-ud-Din Bakhtyār Kāki, Farīduddīn Mas'ūd ("Baba Farid―), Nizamuddin Auliya, Alauddin

Sabir Kaliyāri, Muhammed Badeshā Qādri, Ashraf Jahāngir Semnāni, Hāji Imdadullāh Muhājir

Makki and Shāh Niyāz Ahmad. Chishti master Hazrat Ināyat Khān was the first to bring the

Sufi path to the West.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sufismppt-210817051348/85/Sufism-ppt-13-320.jpg)

![…Sufi Orders

Suhrawardiās [f: Diyā al-din Abu ‗n-Najib as-Suhrawardi (1097-1168)] live in extreme

poverty, spending time in Zikr- remembrance. It is a strictly Sunni order, guided by the Shafi`I

school of Islamic law (Madhab), and, traces its spiritual genealogy to Hazrat Ali ibn Abi

Tālib through Junayd Baghdādi and al-Ghazāli. It played an important role in the formation of

a conservative ‗new piety‘ and in the regulation of urban vocational and other groups, such as

trades-guilds and youth clubs, particularly in Baghdād. Shaikh Umar of Baghdad directed his

disciple Bahā-ud-din Zakariā to Multan and Saiyad Jalāluddin Surkh-Posh Bukhāri to Uch,

Sindh. Bukhāri was a puritan who strongly objected to Hindu influence on Muslim social and

religious practices. The order became popular in India owing to his and of his successor,

Bahā-ud-din Zakariā‘s work. The poet Fakhr-al-Din Irāqi and Pakistani saint Lal Shāhbāz

Qalandar (1177-1274) were connected to the order. The order declined in Multan but became

popular in other provinces like Uch, Gujarat, Punjab, Kashmir, Delhi, Bihar & Bengal.

Naqshbandiās- ‗engravers‘ (of the heart) [f: Hazrat Shāh Bahā al-Din Naqshband (d.1389)]

use a coloured map of an internal stage for Tasawwar, recite the Kalmā in a low voice, follow

Shari‟ā and Habs-i-Dam (Prānāyām). They are most active in Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka,

Pakistan and Brunei and is prevalent in almost all of Europe incl. UK, Germany and France,

and in USA, Middle East, Africa, Syria, Palestine, India, China, Japan, Australia, New Zealand,

Latin America, Azerbeijan, Daghestan (Russia) etc. Bāqi Billāh Berang is credited for bringing

the order to India during the end of the 16th cent. Among his disciples were Shaikh Ahmad

Sirhindi (Mujāddad-i-Alf-i-Thāni) and Shaikh Abdul Haq of Dihli. Some of their other prominent

masters were: Hazrat Abu Bakr as-Siddiq, Hazrat Bāyāzid al-Bistāmi, Bāyāzid al-Bistāmi,

Saiyad Abdul Khāliq al-Ghujdāwani, Hazrat Shāh Naqshband, Saiyad Ubaidullāh al-Ahrār,

Saiyad Ahmad al-Faruqi, Shaikh Khālid al-Baghdādi, Saiyad Shaikh Ismāil Shirwāni.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sufismppt-210817051348/85/Sufism-ppt-14-320.jpg)

![Remembrance (Zikr)

Zikr is a preparatory, but essential exercise going upto Third Eye (Nuqtā-i-Swaidā, Mehrāb

or Qalāb-i-Munib) focus. It is invocation and remembrance of Divine names or some religious

formula, which are repeated, accompanying the intonation with intense concentration of every

faculty, to enjoy uninterrupted communion with God. The name gets itself established in their

tongues, heart and soul. This is the key to Mārifat or access to the Divine Mysteries.

Zikr may be either spoken or silent, but tongue and mind should co-operate. Its first stage

is to forget self, and last stage is self-effacement. Recollection eventually becomes part and

parcel of his life. Due to concentration, certain Riddhi-Siddhis- supernatural powers are

invested. Sufis attach greater value to Zikr, than to five Namāzes at fixed hours of the day.

Zikr can be: 1. Nasooti (of tongue): initially prescribed, as audible Zikr permeates the entire

body. 2. Malkooti (of heart): thru perfection in Habs-i-Dam (Pranayam). 3. Jabrooti (of spirit):

results in tranquility in the consciousness. It requires mastery in withdrawal of senses.

4. Lahooti (of mind): aspirant projects love (Muhabbat) for the All-Pervading Divine.

Types of Zikrs: Zikr-i-Qalāb (Shugal-i-Isā-i-Zāt): begins with Qalab-i-Sanobari at the

physical heart and rises upto Third Eye. [Qalāb-i-Salib is the ‗heart‘ at Trikuti]. ~Fahmidā:

done, keeping focus on tip or root of the nose. Zikr-i-Pas-o-Anfās (Shwāsa Sohang):

done with rhythm of breath. ‗Allah‘ is mentally repeated while inhaling, ‗Hu‘ while exhaling.

~Ismā-i-Rabbāni: prescribed Divine names are repeated everyday. ~Zarābi: thrusts are

applied on the heart in order to scan it. ~Ārā: by visualizing Satan being bisected, while

striking the heart. ~ Latifā: by concentrating on the Latifās and awakening them thru Zikr.

~ Sultan-ul-Azkār: the king of all Zikr. Latifās are activated by deep concentration, without

Habs-i-Dam, but with repetition of Divine names. Finally, focus is laid on the senses. Other

Zikrs: such as: ~Aitā-ul-Karsi, ~Haddāvi, ~Karā Haidri, ~Makashfāh, ~Fanā-o-Baqā.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sufismppt-210817051348/85/Sufism-ppt-22-320.jpg)

![ The first of the theosophical speculations based on mystical insights about human nature

and the essence of the Prophet Muhammad were produced by such Sufis as Sahl al-Tustarī,

who was the master of al-Ḥallāj, who has become famous for his phrase anā al-ḥaqq,

―I am the Creative Truth‖ (often rendered ―I am God‖), which was later interpreted in a

pantheistic sense but is, in fact, only a condensation of his theory of huwā huwā (―He he‖):

God loved himself in his essence, and created Adam ‘in his image.‘ His few poems are of

exquisite beauty; his prose, which contains an outspoken Muhammad-mysticism i.e.,

mysticism centred on the Prophet, is as beautiful as it is difficult.

In these early centuries Sufi thought was transmitted in small circles. Some of the Shaikhs,

Sufi mystical leaders or guides of such circles, were also artisans. In the 10th cent., it was

deemed necessary to write handbooks about the tenets of Sufism in order to soothe the

growing suspicions of the orthodox; the compendiums composed in Arabic by Abū Ṭālib

Makkī, Sarrāj, and Kalābādhī in the late 10th cent., and by Qushāyrī and, in Persian, by

Hujwīrī in the 11th cent. reveal how these the mystics, belonging to all schools of Islamic law

and theology of the times, tried to defend Sufism and to prove its orthodox character.

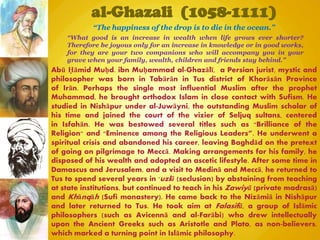

The last great figure in the line of classical Sufism is Abū Hamid al-Ghazālī, who wrote,

among numerous other works, the Iḥyāulūm al-dīn (‗The Revival of the Religious Sciences‘),

a comprehensive work that established moderate mysticism against the growing theosophical

trends, which tended to equate God and the world, and thus shaped the thought of millions of

Muslims. His younger brother, Aḥmad al-Ghazālī, wrote one of the subtlest treatises, Sawāniḥ

(‗Occurrences‘ [i.e., stray thoughts]) on mystical love, a subject that then became the main

subject of Persian poetry.

Sufism as Islamic Mysticism](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sufismppt-210817051348/85/Sufism-ppt-47-320.jpg)

![ From its beginning, Islam has been a central feature in Africa, which was the first continent

into which it expanded. Sufism has many orders as well as followers in W Africa, Algeria and

Sudan. In Morocco and Senegal, Sufism is seen as a mystical expression of Islam,

accommodating local beliefs and customs, which tend toward the mystical. Most orders in W

Africa emphasize the role of a spiritual guide, Marābout or possessing supernatural power.

Sufi brotherhoods appeared in or south of the Sahara desert around 1800. In the 17th-18th

cents. individuals like al-Mukhtār al-Kunti and Uways al-Barāwi of Qadiriā, al-Hajj 'Umar Sa‘id

Tall of Tijāniā, Ibn Idris and Shaikh Mā'ruf of Shadhillā ‗set the directions‘ of their orders. In

Senegal & Gambia, Mouridism Sufis have several million adherents and venerate its founder,

Amadou Bambā Mbacké (d. 1927). Sufism has seen a growing revival in Morocco with

contemporary spiritual teachers such as Sidi Hamzā al Qādiri al Boutshishi. Notable are:

Algerian Emir Abd al-Qādir, Amadou Bambā, Shaikh Mansur Ushurmā & Imām Shāmil.

Egypt: During the middle of the 19th cent. Egypt was inhabited and controlled by Naqsh-

bandis. A major Naqshbandiā Khānqāh was constructed in 1851 for Shaikh Ahmad Ashiq (of

Diyā'iā branch of the Khālidiā). During the last two decades of the 19th cent. two other versions

of Naqshbandiā spread in Egypt. One of these was introduced by Sudanese, al-Sharif Ismā'il

al-Sinnāri into Upper Egypt from 1870 from Sudan. The Judiā and the Khalidiā branches

spread in the last decades of the 19th cent. and are still active today.

The Chishti Sābiri Jahāngiri Silsilā [named after Hzt. Makhdoom Alauddin Ali Ahmed Sābir

Kalyāri, a successor to Bābā Farid & Saiyad Muhammad Jahāngir Shāh Chishti Sābri of

Ajmer (d. 1924)] was brought to Durban, S. Africa by Jnb. Ebrahim Madāri Chishti Sābiri in

1944.

Sufism in Africa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sufismppt-210817051348/85/Sufism-ppt-62-320.jpg)