- The document analyzes a dataset relating body fat percentage to various measurements to find a predictor.

- It finds that abdominal circumference has the highest correlation (0.81) to body fat percentage. A linear regression model is fitted with abdominal circumference predicting body fat percentage.

- The model is found to be statistically significant and explains 66.21% of the variability in body fat percentage based on the abdominal circumference measurement.

![Task 3

In Task 3, we are asked to test the claim by researchers that the average body fat percentage is

less than 12.5. This claim corresponds to the mathematical statement that , which is

equivalent to since the probability that is precisely 12.5 is zero.

For simplicity we can take the following as our null and alternative hypotheses:

This is justified because statistically significant support for our alternative hypothesis will lead to a

rejection of the statement made by the researchers.

We use the p-value approach.

m<-mean(Bodydata$BFP_Brozek)

mu<-12.5

s<-sd(Bodydata$BFP_Brozek)

n<-length(Bodydata$BFP_Brozek)

se<-s/sqrt(n)

t<-(m-mu)/se

t

## [1] 13.18666

pt(t,df=n-1, lower.tail=FALSE)

## [1] 7.994808e-31

This p-value is extremely small and we would round it to 0.001. It is certainly far smaller than 0.05,

and so the result is statistically significant. In other words, our data gives statistically significant

evidence that the claim average body fat percentage is less than 12.5 is incorrect, because the

probability of observing our sample statistic under the assumption that the claim is true is near zero.

Task 4

In Task 4 we seek to investigate a means of predicting body fat percentage using body

circumference data. The data set includes ten different circumference measurements, and our first

step is to identify the single best predictor.

The Pearson Correlation Coefficient was used to make this identification. For each of the ten

different circumference measurements, the code below was used to measure the correlation with

body fat percentage. The results were:

Circumference Measurement (cm) Pearson Correlation with BFP

Neck 0.49

Chest 0.7

μ < 12.5

μ ≤ 12.5 μ

: μ = 12.5H0

: μ > 12.5HA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/math1324assignment3-180827055119/85/Statistics-Project-3-320.jpg)

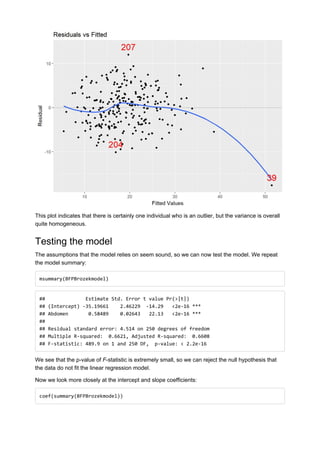

![## [1] 39 207

There don’t appear to be any major deviations from normality.

Homoscedasticity

Homoscedasticity can be observed by looking at a scatter plot of predicted values against residuals.

mplot(BFPBrozekmodel, 1)

## [[1]]

## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'loess'](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/math1324assignment3-180827055119/85/Statistics-Project-6-320.jpg)

![## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -35.1966077 2.46229413 -14.29423 2.790180e-34

## Abdomen 0.5848905 0.02642528 22.13375 7.706457e-61

The null and alternative hypotheses for the intecept are:

We compute the two-tailed p-value for this constant:

2*pt(-14.29423,252-2,lower.tail=TRUE)

## [1] 2.790261e-34

Since this value is less than 0.05, the intercept is statistically significant.

The null and alternative hyptheses for the slope are:

We compute the two-tailed p-value for this slope:

2*pt(22.13375,252-2,lower.tail=FALSE)

## [1] 7.706439e-61

Again, the p-value is much less than 0.05 so the slope is statistically significant.

95% Confidence Intervals for intercept and slope can also be calculated:

confint(BFPBrozekmodel)

## 2.5 % 97.5 %

## (Intercept) -40.046092 -30.3471234

## Abdomen 0.532846 0.6369351

The following plot summarises the linear relationship between Abdominal Circumference and Body

Fat Percentage as measured by the Brozek method.

xyplot(BFP_Brozek ~ Abdomen, data = Bodydata, ylab ="BFP_Brozek", xlab="Abdominal C

ircumference (cm)", panel=panel.lmbands)

α

: α = 0H0

: α ≠ 0HA

β

: β = 0H0

: β ≠ 0HA](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/math1324assignment3-180827055119/85/Statistics-Project-8-320.jpg)