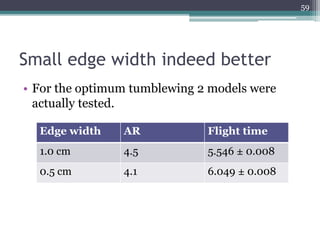

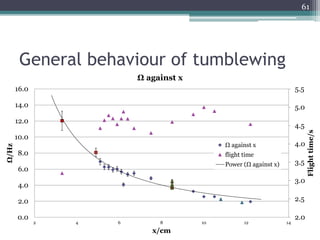

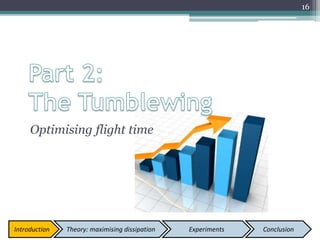

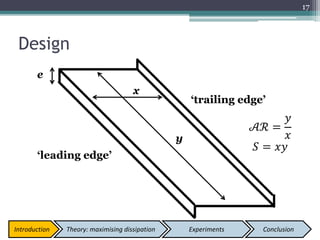

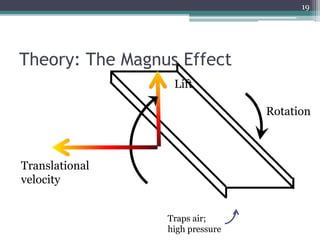

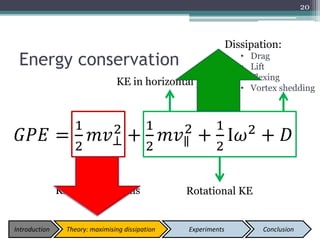

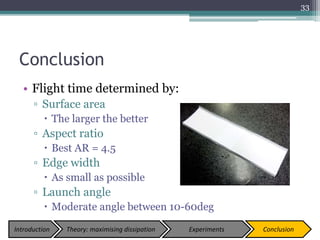

The document describes experiments to design a paper device that falls slowly through the air. It summarizes that a tumblewing design, which rotates and moves horizontally, works best by maximizing surface area for drag. Testing showed flight time increased with higher aspect ratio around 4.5, smaller edge width, and moderate launch angles between 10-60 degrees. The optimum design had an aspect ratio of 4.1, surface area of 573.5 cm^2, and edge width of 0.5 cm, achieving a maximum flight time of 6.5 seconds.

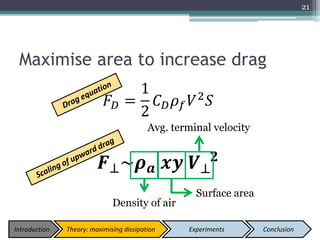

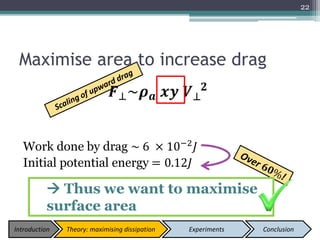

![[1] Effect of aspect ratio

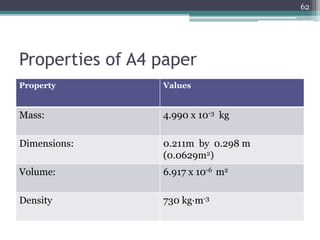

• Independent variable: Aspect ratio y/x

• Dependent variable

▫ Flight time

• Constants:

▫ Area, xy (450±3)cm2

▫ Edge width (1.00±0.05)cm

▫ Mass (4.990±0.005)g

▫ Launch angle (45.0±0. 5)deg

24

x

y

3.0 4.1 4.5 5.0 6.2 8.0 10.0

11.0 11.7 12.1 12.9 13.9 14.9 16.0 17.2

Introduction Theory: maximising dissipation Experiments Conclusion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2ffcaef6-6431-4e80-939e-2502b734b7c9-170114042537/85/Slow-descent-v3_IYPT-24-320.jpg)

![[1] Effect of aspect ratio

25

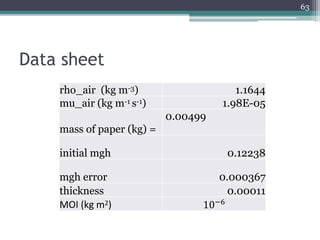

4.00

4.20

4.40

4.60

4.80

5.00

5.20

1.0 6.0 11.0 16.0

Flighttime/s

Aspect ratio

Flight time against AR

Introduction Theory: maximising dissipation Experiments Conclusion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2ffcaef6-6431-4e80-939e-2502b734b7c9-170114042537/85/Slow-descent-v3_IYPT-25-320.jpg)

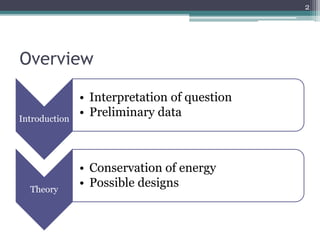

![• Variable: edge width, e

▫ 0.3 0.6 0.9 1.0 1.2 1.5 1.8 2.1cm

• Constants:

▫ Span, y (45.00±0.05)cm

▫ Chord, x (10.00±0.05)cm

▫ Launch angle (45.0±0. 5)deg

• Assumption:

▫ Change in mass will not affect

flight time

[2] Effect of edge width

26

e

x

y

Introduction Theory: maximising dissipation Experiments Conclusion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2ffcaef6-6431-4e80-939e-2502b734b7c9-170114042537/85/Slow-descent-v3_IYPT-26-320.jpg)

![[2] Effect of edge width

27

3.00

3.50

4.00

4.50

5.00

5.50

6.00

0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5

Flighttime/s

Edge width /cm

Flight time against edge width

Introduction Theory: maximising dissipation Experiments Conclusion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2ffcaef6-6431-4e80-939e-2502b734b7c9-170114042537/85/Slow-descent-v3_IYPT-27-320.jpg)

![[3] Effect of launch angle

• Variable: Launch angle θ

▫ 0 – 120deg, at 10deg intervals

• Dependent variable:

▫ time

• Constants:

▫ Span, y (45.00±0.05)cm

▫ Chord, x (10.00±0.05)cm

▫ Edge width (1.00±0.05)cm

28

θ

Direction of flight

Introduction Theory: maximising dissipation Experiments Conclusion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2ffcaef6-6431-4e80-939e-2502b734b7c9-170114042537/85/Slow-descent-v3_IYPT-28-320.jpg)

![[3] Effect of launch angle

29

Introduction Theory: maximising dissipation Experiments Conclusion

“Dead

Zone”

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

5.5

6.0

0.0 20.0 40.0 60.0 80.0

Flighttime/s

θ/deg

Flight time against launch angle](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2ffcaef6-6431-4e80-939e-2502b734b7c9-170114042537/85/Slow-descent-v3_IYPT-29-320.jpg)

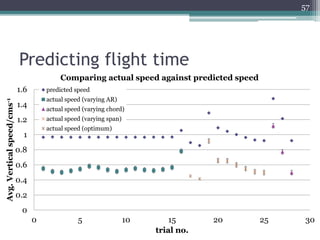

![[4] The best tumblewing

• Characteristics:

▫ AR of 4.5

▫ Maximum surface area

▫ Small edge width

▫ Moderate launch angle

• Optimum model:

30

Span/cm Chord/cm AR SA/cm2 Edge/cm

48.6 11.8 4.1 573.5 0.5

Introduction Theory: maximising dissipation Experiments Conclusion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2ffcaef6-6431-4e80-939e-2502b734b7c9-170114042537/85/Slow-descent-v3_IYPT-30-320.jpg)

![[4] The best tumblewing

31

2.00

2.50

3.00

3.50

4.00

4.50

5.00

5.50

6.00

6.50

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

Flighttime/s

Wing no.

Comparing flight times optimum

varying aspect ratio

varying chord

varying span

Introduction Theory: maximising dissipation Experiments Conclusion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2ffcaef6-6431-4e80-939e-2502b734b7c9-170114042537/85/Slow-descent-v3_IYPT-31-320.jpg)

![[blank]

35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2ffcaef6-6431-4e80-939e-2502b734b7c9-170114042537/85/Slow-descent-v3_IYPT-35-320.jpg)

![[blank]

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2ffcaef6-6431-4e80-939e-2502b734b7c9-170114042537/85/Slow-descent-v3_IYPT-36-320.jpg)

![[blank]

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2ffcaef6-6431-4e80-939e-2502b734b7c9-170114042537/85/Slow-descent-v3_IYPT-37-320.jpg)