This document summarizes the design and results of a test rig to measure lift force generated by flapping wings. Numerical modeling was used to predict lift values based on wing geometry and motion parameters like frequency and angle of attack. An experimental test rig was designed and built with servo motors in the wings to control twisting instead of relying on flexibility. Force measurements from the rig were taken using a load cell as frequency and angle of attack were varied. Results showed that increasing frequency and angle of attack both increased lift force as expected based on the numerical predictions. The document provides context on bio-inspired flight and reviews other flapping wing projects to inform the design of the test rig.

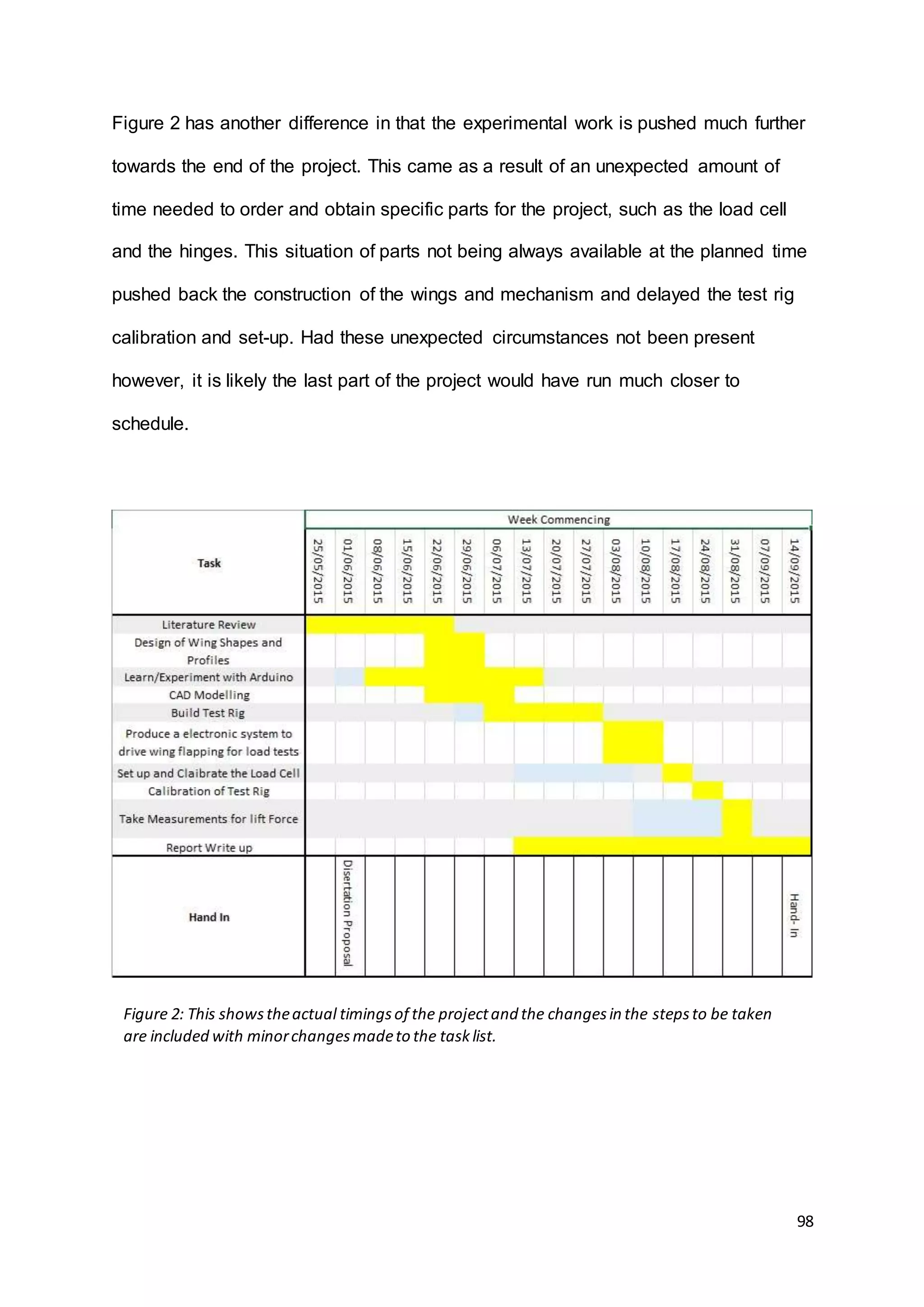

![8

helicopter system could not. It is this versatility which makes a viable Bio-Inspired

flapping wing vehicle a desirable asset for many applications.

4.2. Objectives

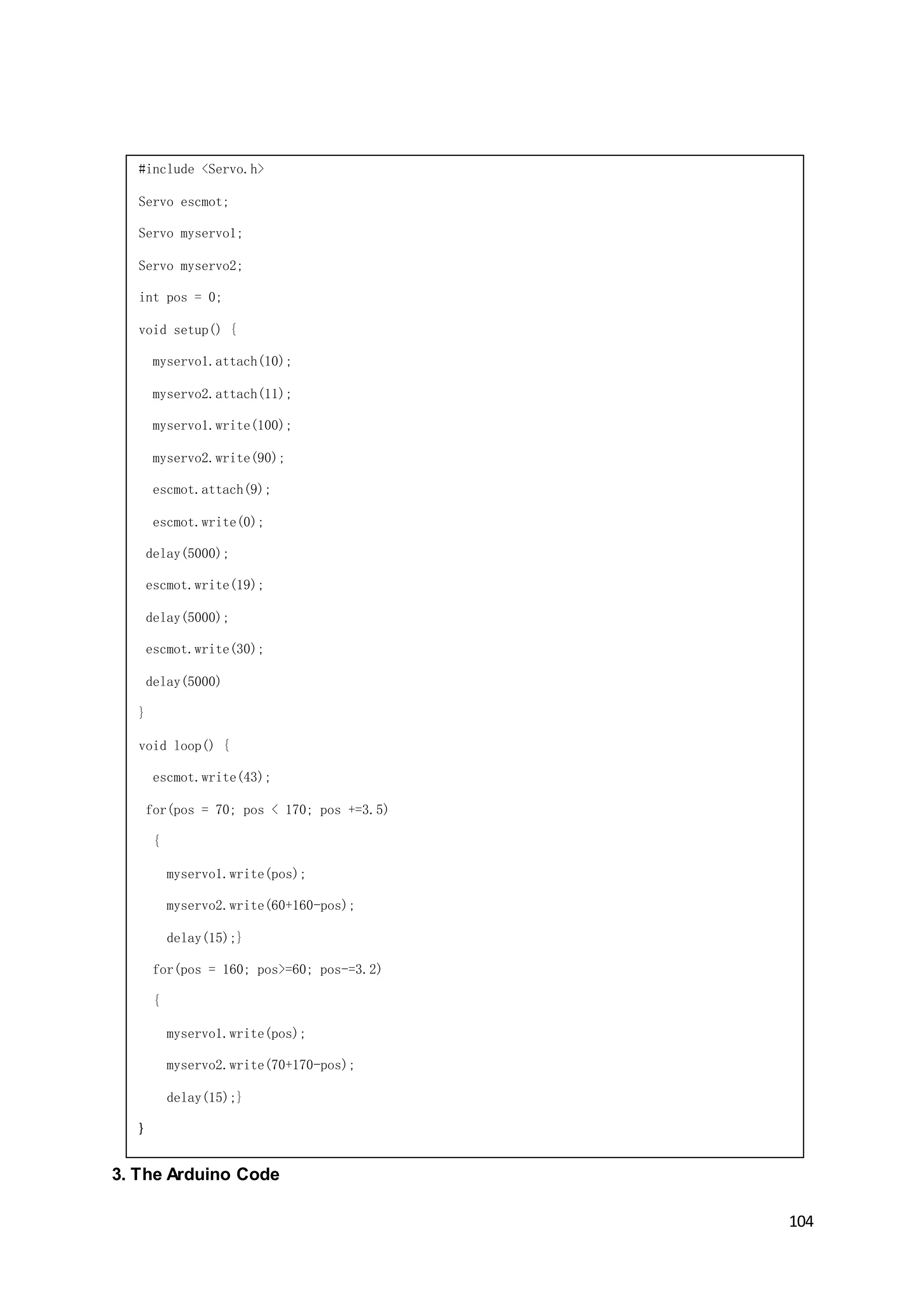

The main focus of the project will be the measurement of Lift Force exerted by a pair

of flapping wings. Where natural examples use passive wing flexibility [1], which

provides the necessary characteristics to a birds wings relative to the conditions they

experience. The design of the test rig however will seek to use servo motors in built

to the wing to replace the need for wing flexibility and its complex design problems.

As much as possible, inspiration will be taken from biological examples with regard

to the shape of aerofoil used and wing geometry. Analysis of the wings will be

carried out numerically to obtain predicted values for Lift Force in the planned

studies for the increase in frequency and stroke Angle of Attack (α).

With results predicted for the test rig, the design will then be finalised and

constructed. This will seek to use, if possible the same material that would be used

should the design be applied to a flight vehicle. The design of the test rig will

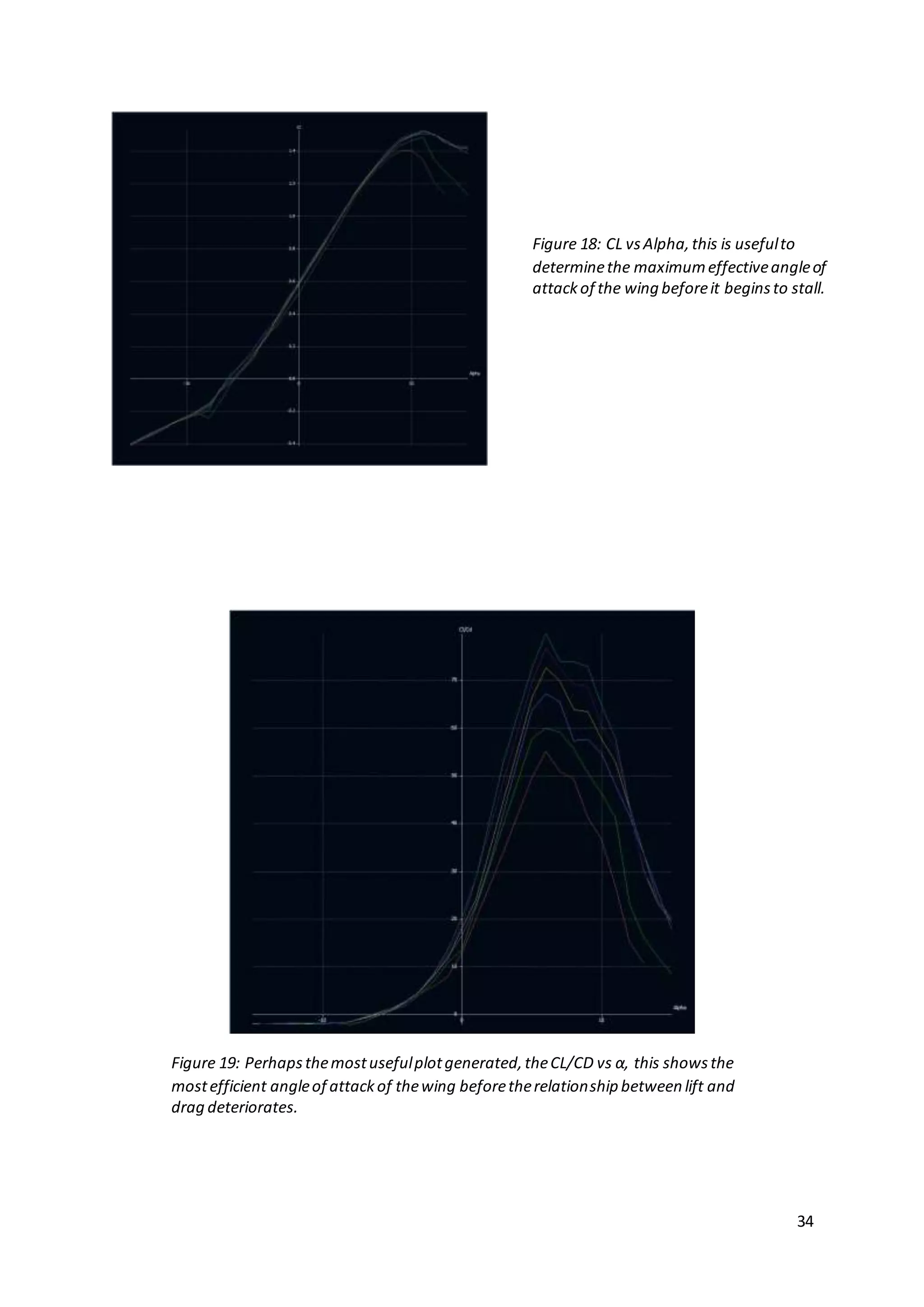

incorporate a pair of wings each with an internally mounted servo in order to twist the

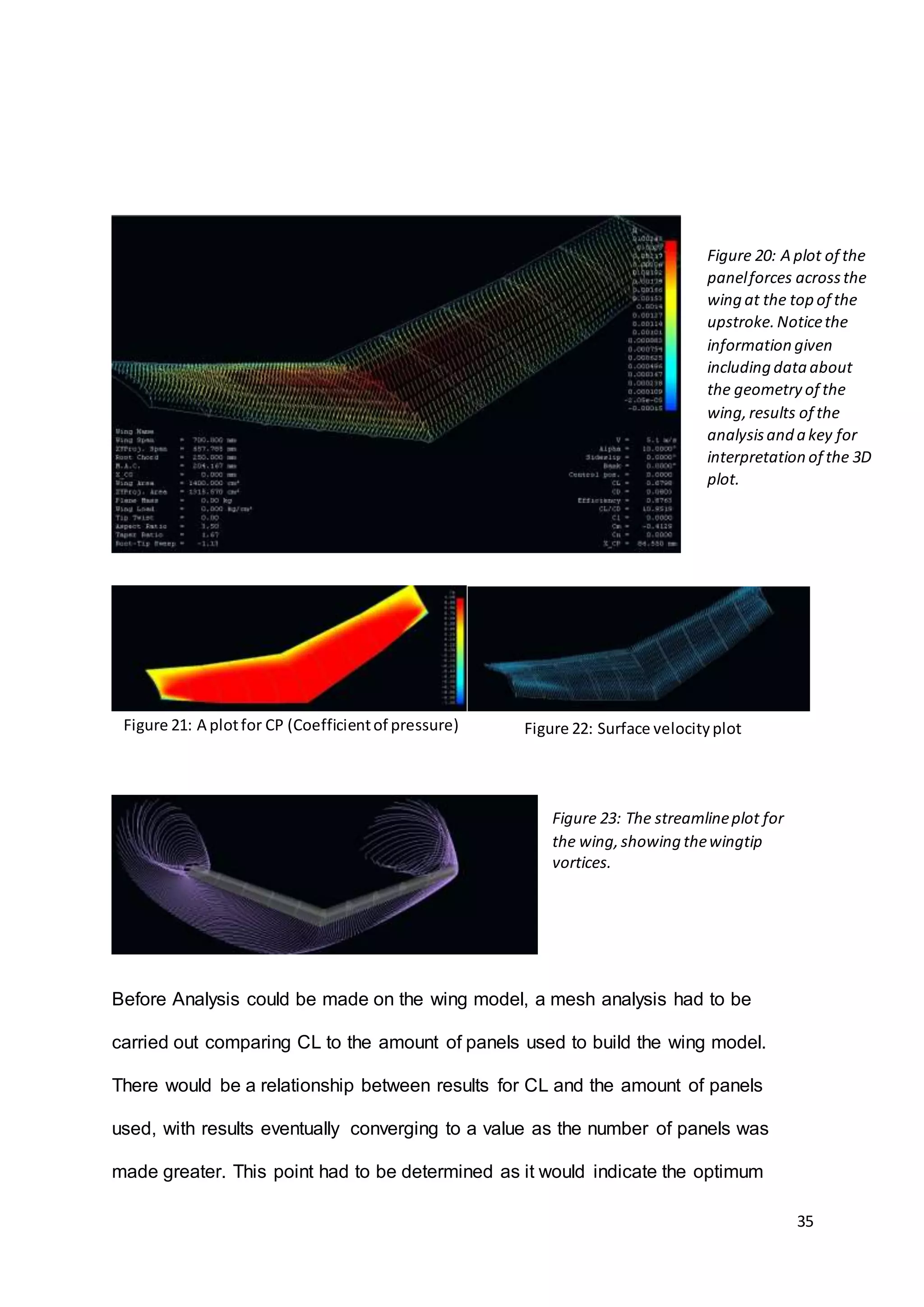

wing, as well as a frame which will hold the wings, motor and mechanism necessary

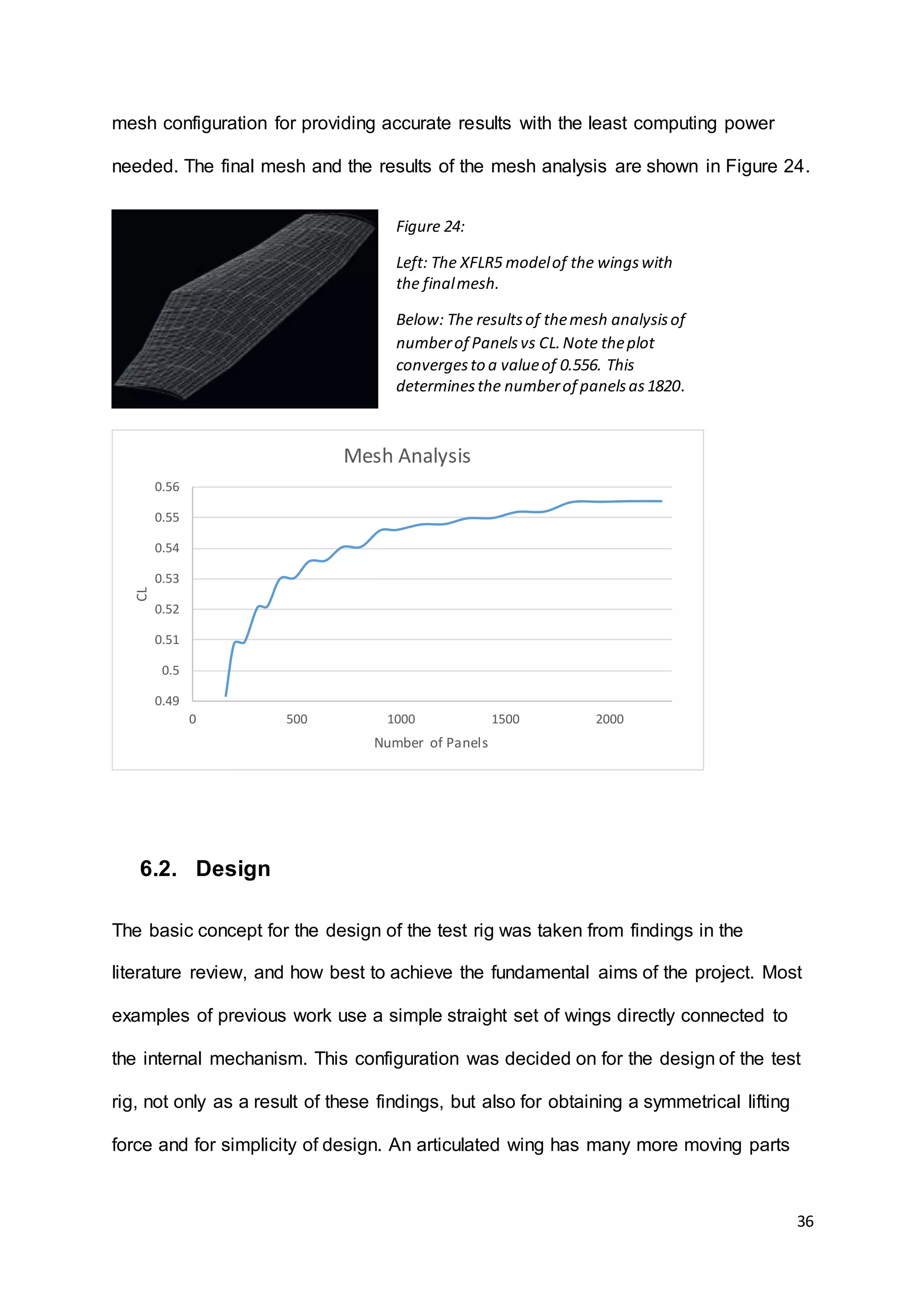

for their flapping motion. Control will be achieved with the use of an Arduino board,

this was selected due to the ease of controlling servos and a brushless motor.

The measurement of the results experimentally will be achieved by the use of a load

cell. This decision was made through the experience of the inadequacy of strain

gauges mounted on a stand holding the test rig. This would allow force to be

measured in a single direction with the direct output relationship to force being

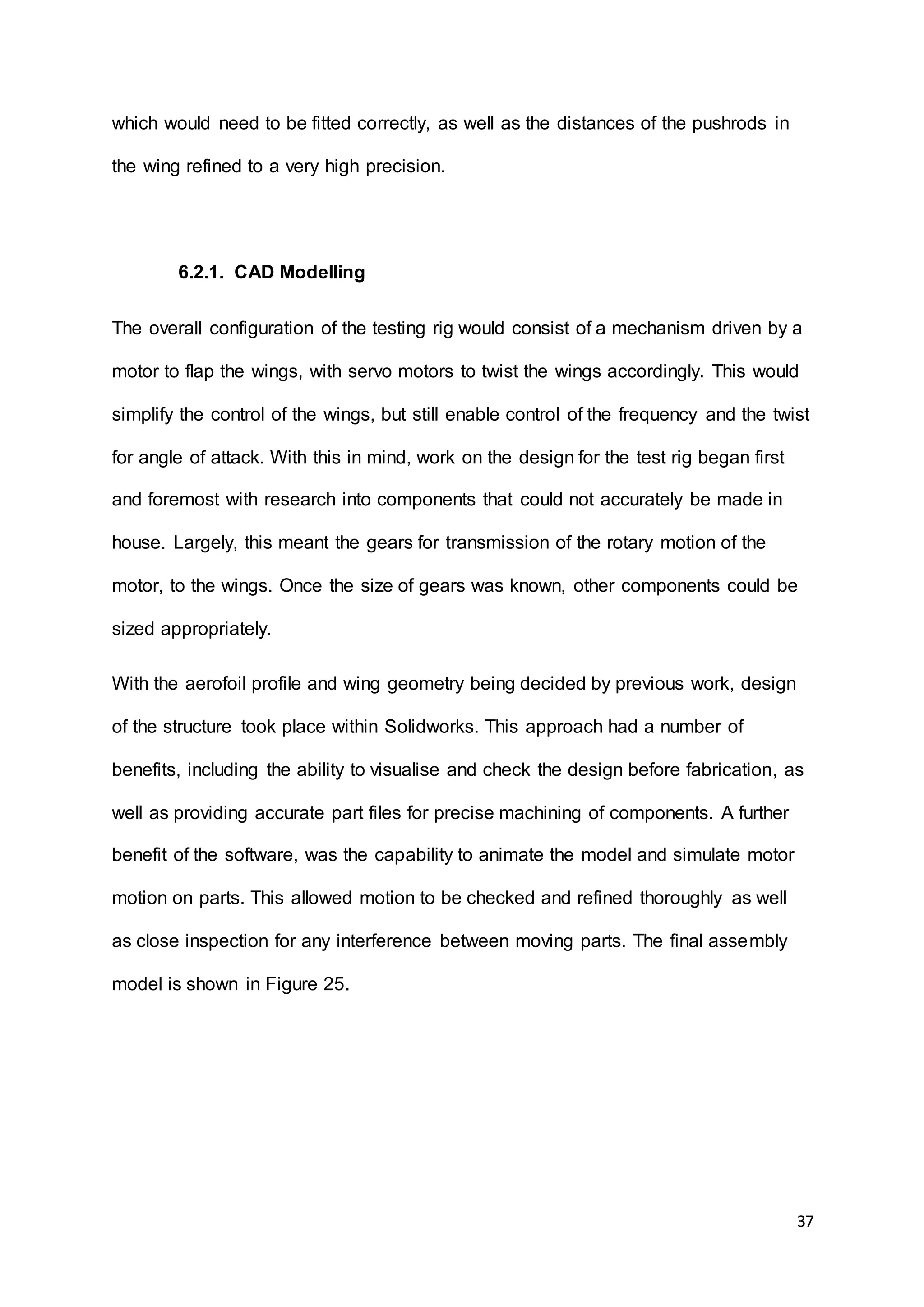

extremely attractive with regard to the processing time of results. The load cell would](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-8-2048.jpg)

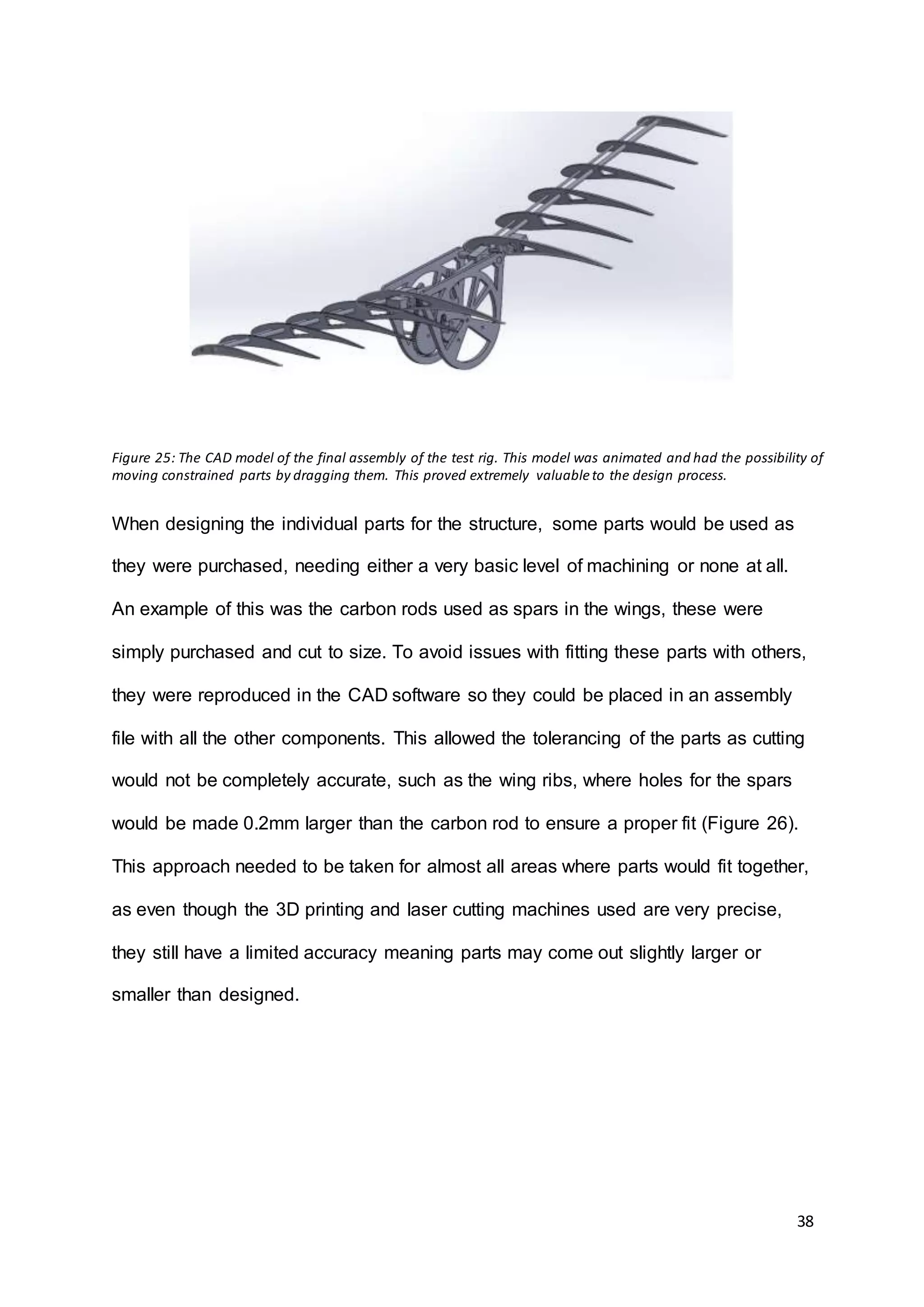

![10

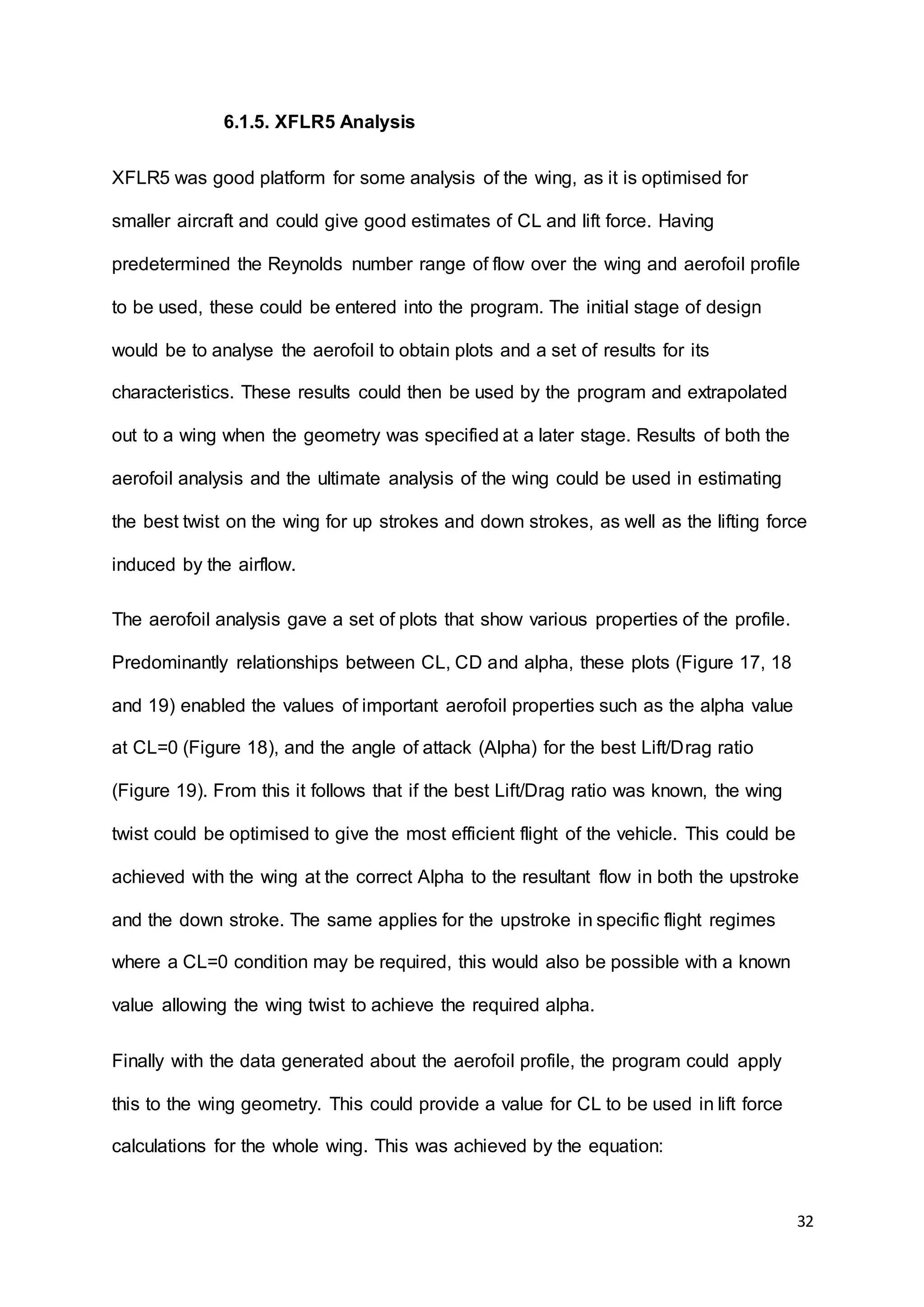

alongside the wing geometry. XFLR5 can then analyse the wing using data from an

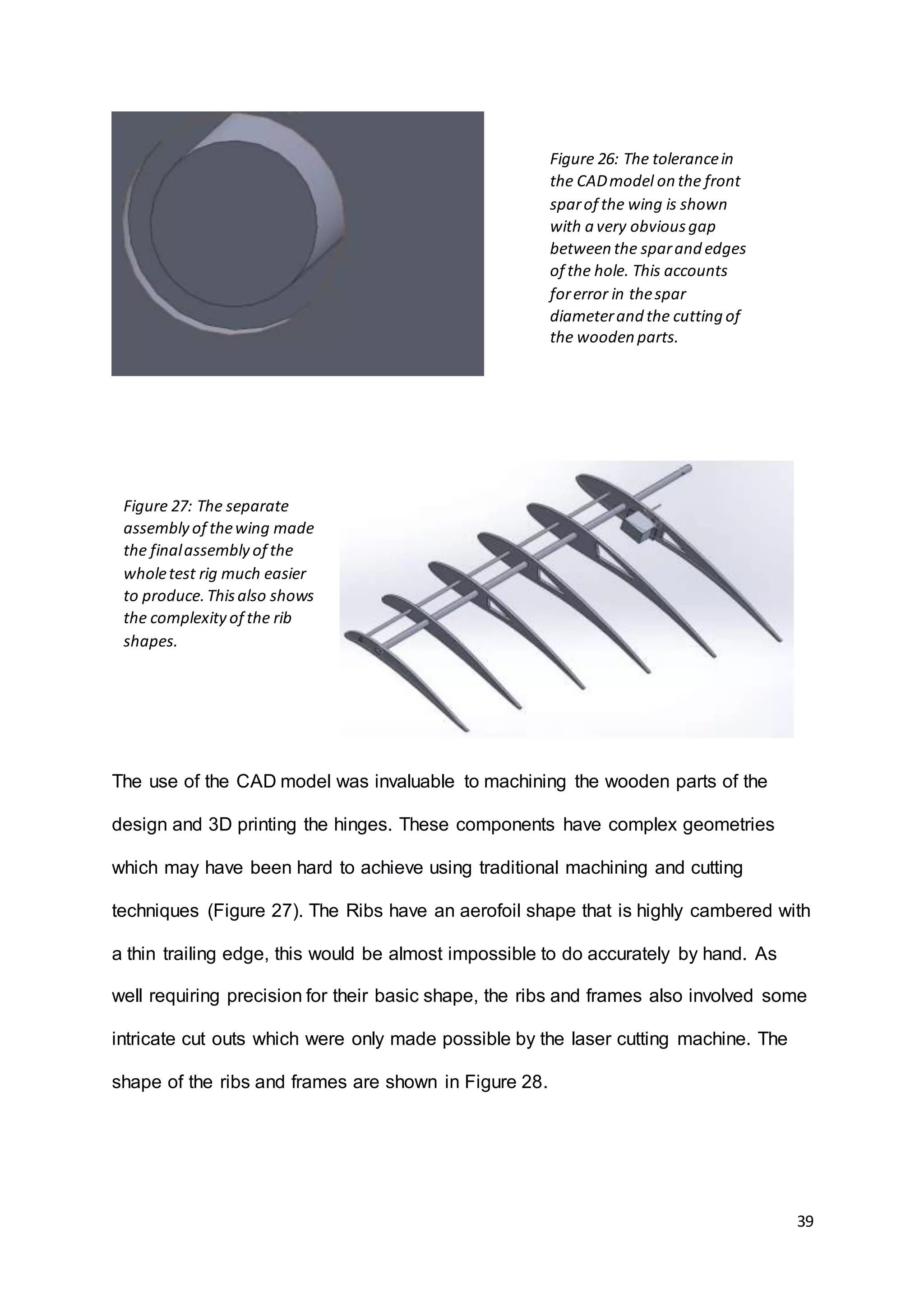

aerofoil analysis, which is also conducted in the software, to produce values for CL.

The second method of obtaining Lift Force will be using equations and methods used

in previous work and applying these to the predicted changes in the parameters of

Flap Angle (φ) and α.

The measurement of experimental data will be done over two studies. The first will

be the increase in frequency over two different Angle of Attack configurations. One

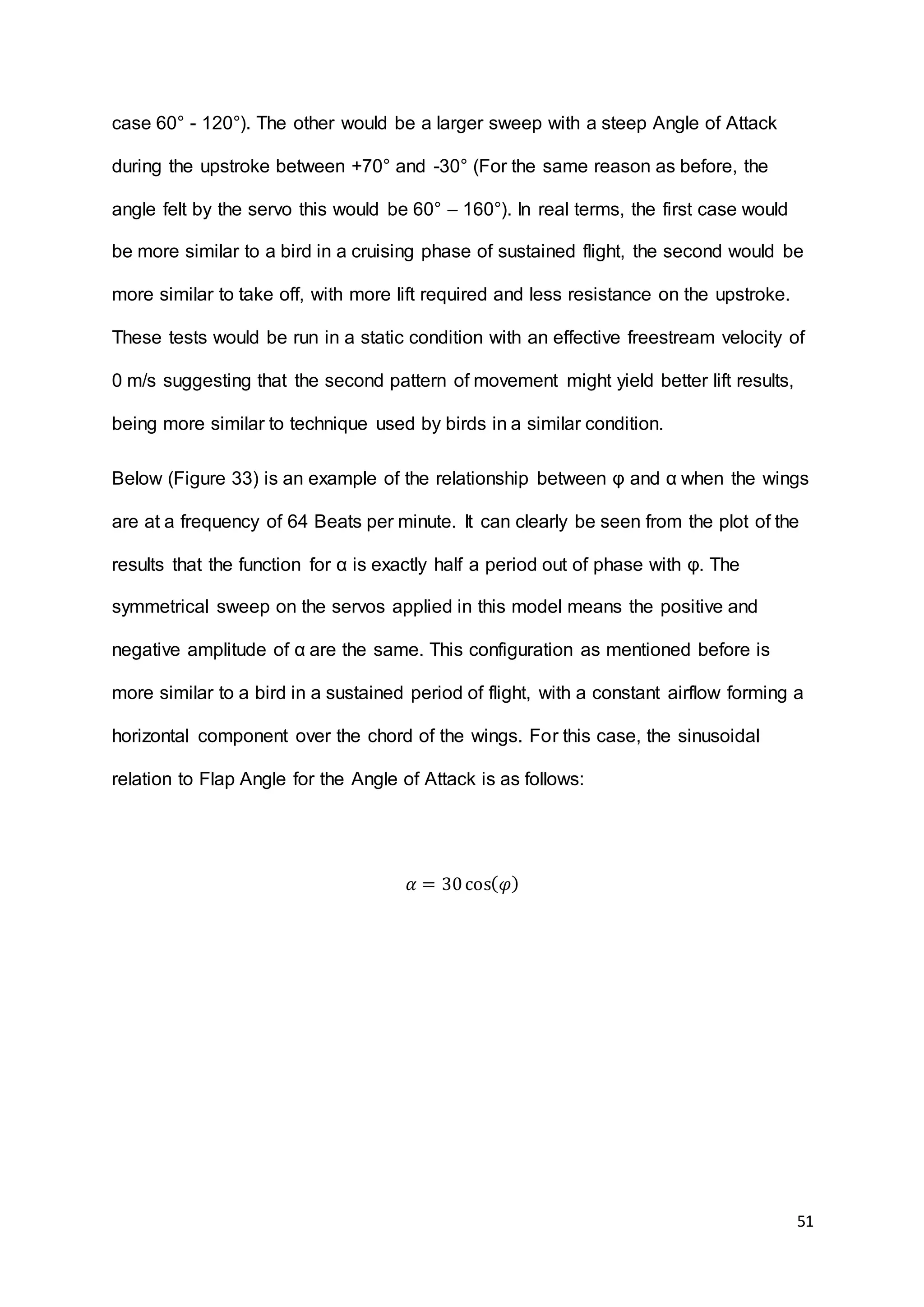

with a symmetrical movement between identical values of positive and negative α.

The other with a high positive Angle of Attack with the aim of creating a more

efficient pattern of movement. The second study will be into the Angle of Attack

achieved at the peak velocity point of the downstroke, this will aim to determine if Lift

Force is increased with a larger negative α or to find its optimal value. The result of

each set case for testing will be analysed using the same method as used by Sane

S.P. (2001) [2] where multiple wing strokes are taken and averaged into a dataset for

a single wing stroke.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-10-2048.jpg)

![11

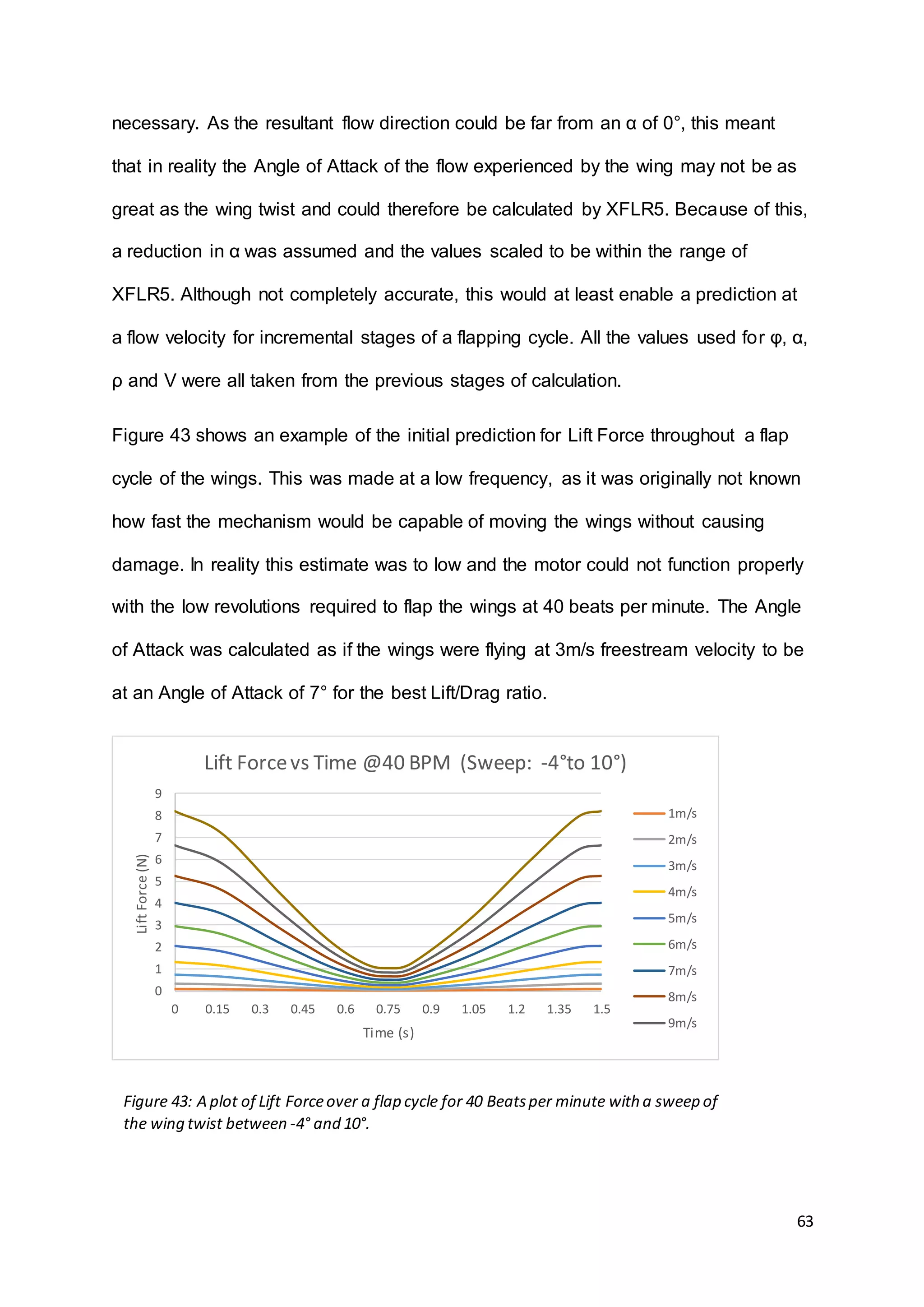

5. Literature Review

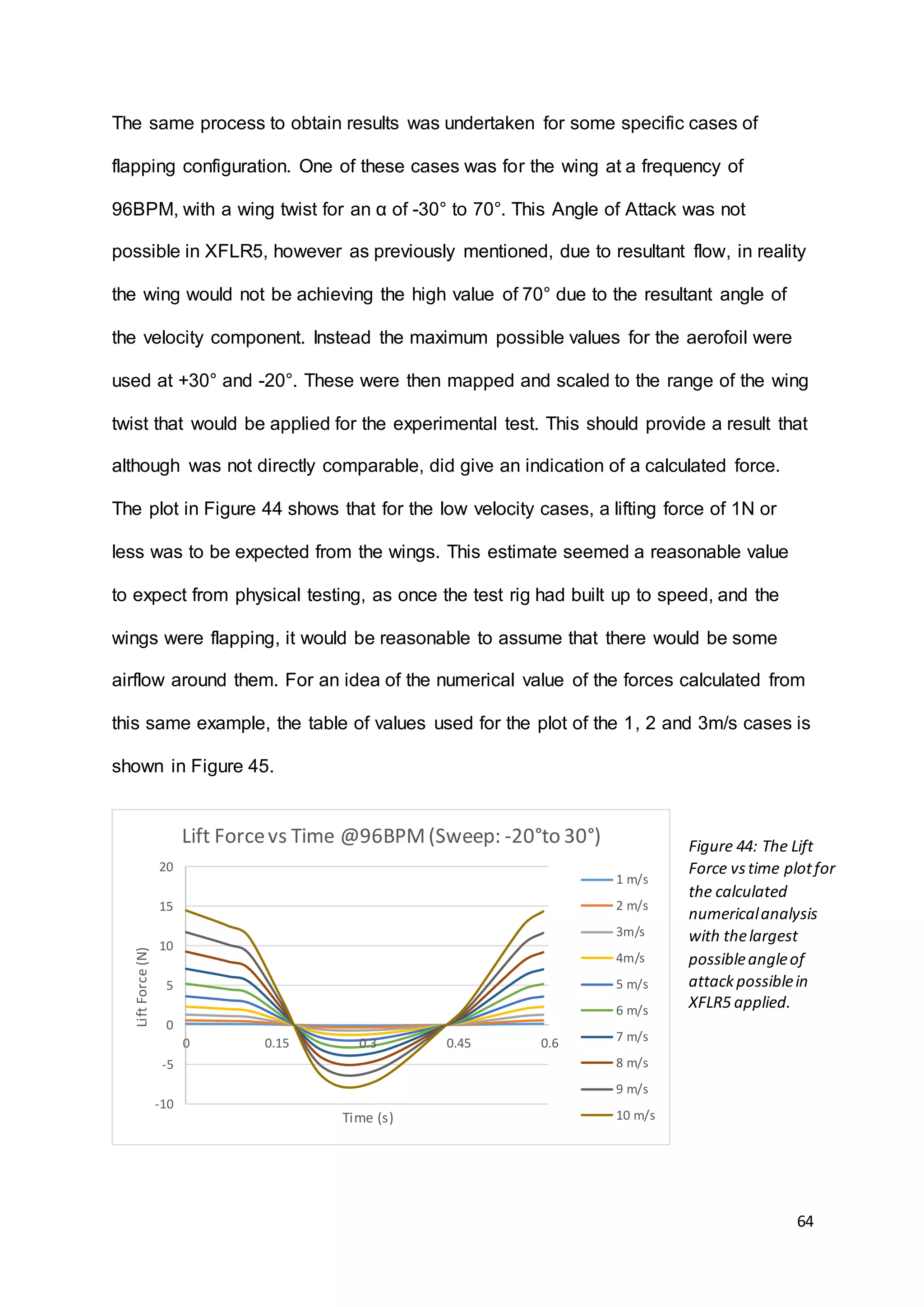

5.1. Notable Projects

5.1.1. Festo Smartbird

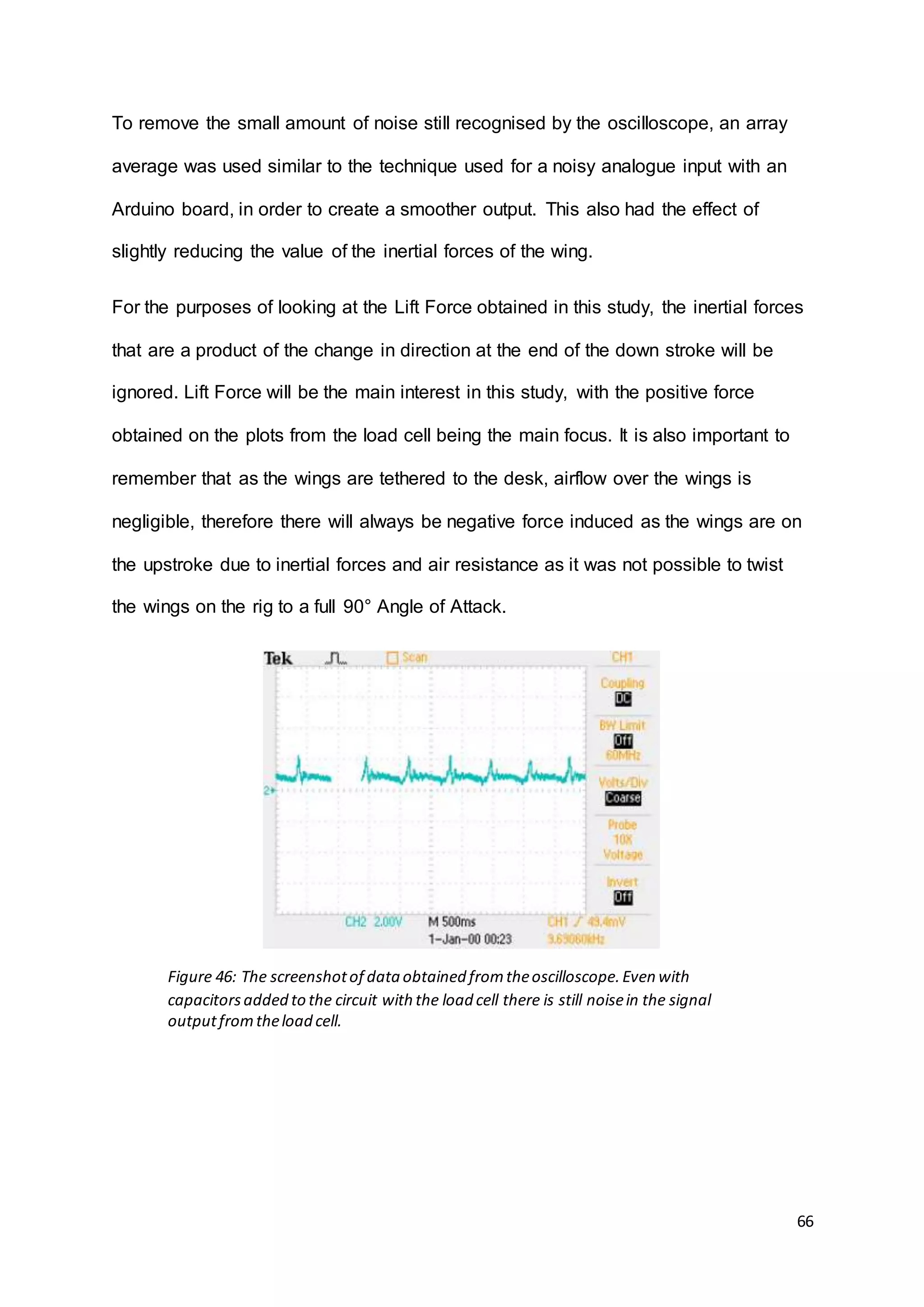

Perhaps the most successful attempt at recreating bird flight, this example uses a

lightweight carbon structure, weighing only 450grams with a wingspan of nearly

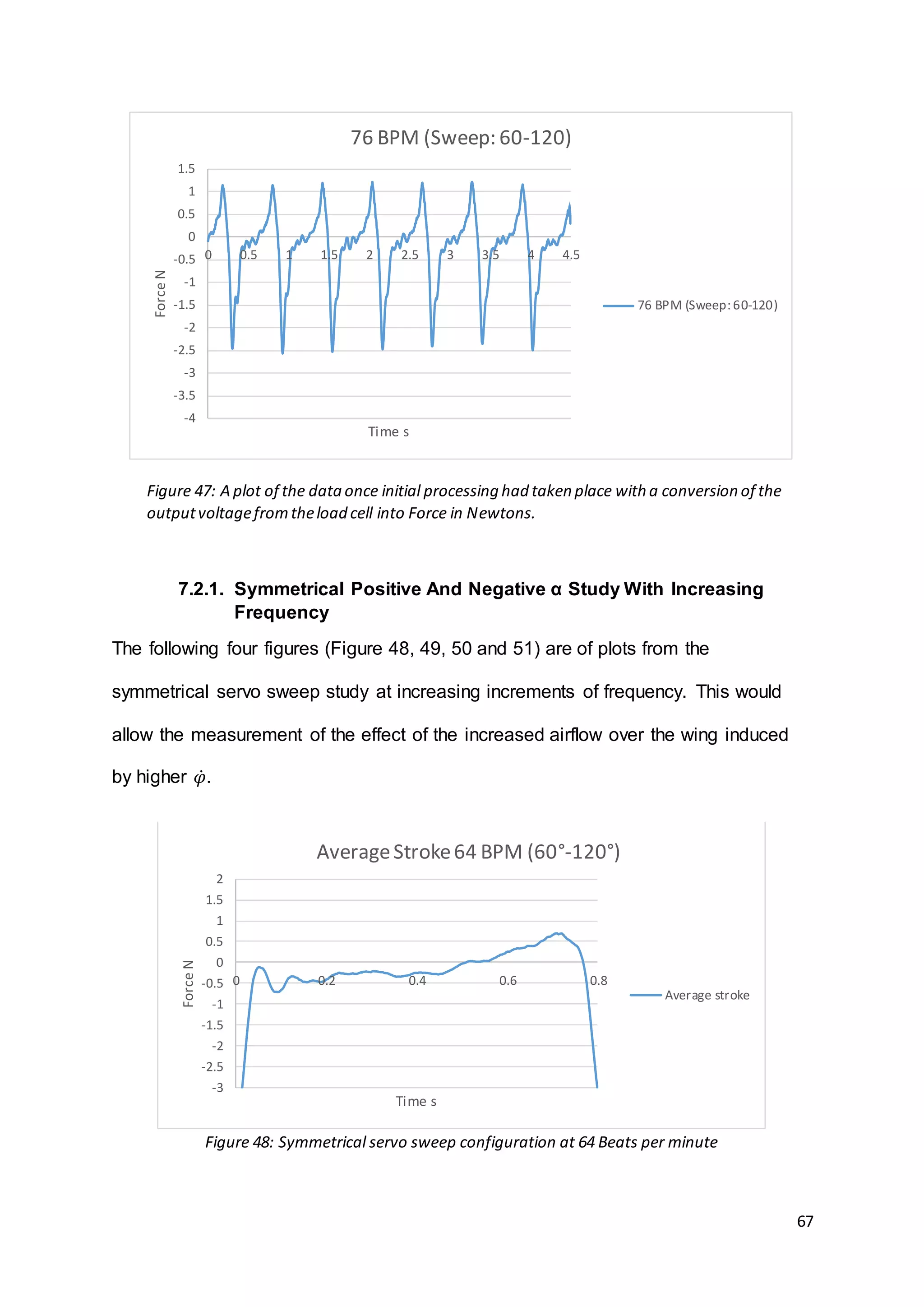

2meters. A high gearing ratio between the motor and the mechanism ensures that a

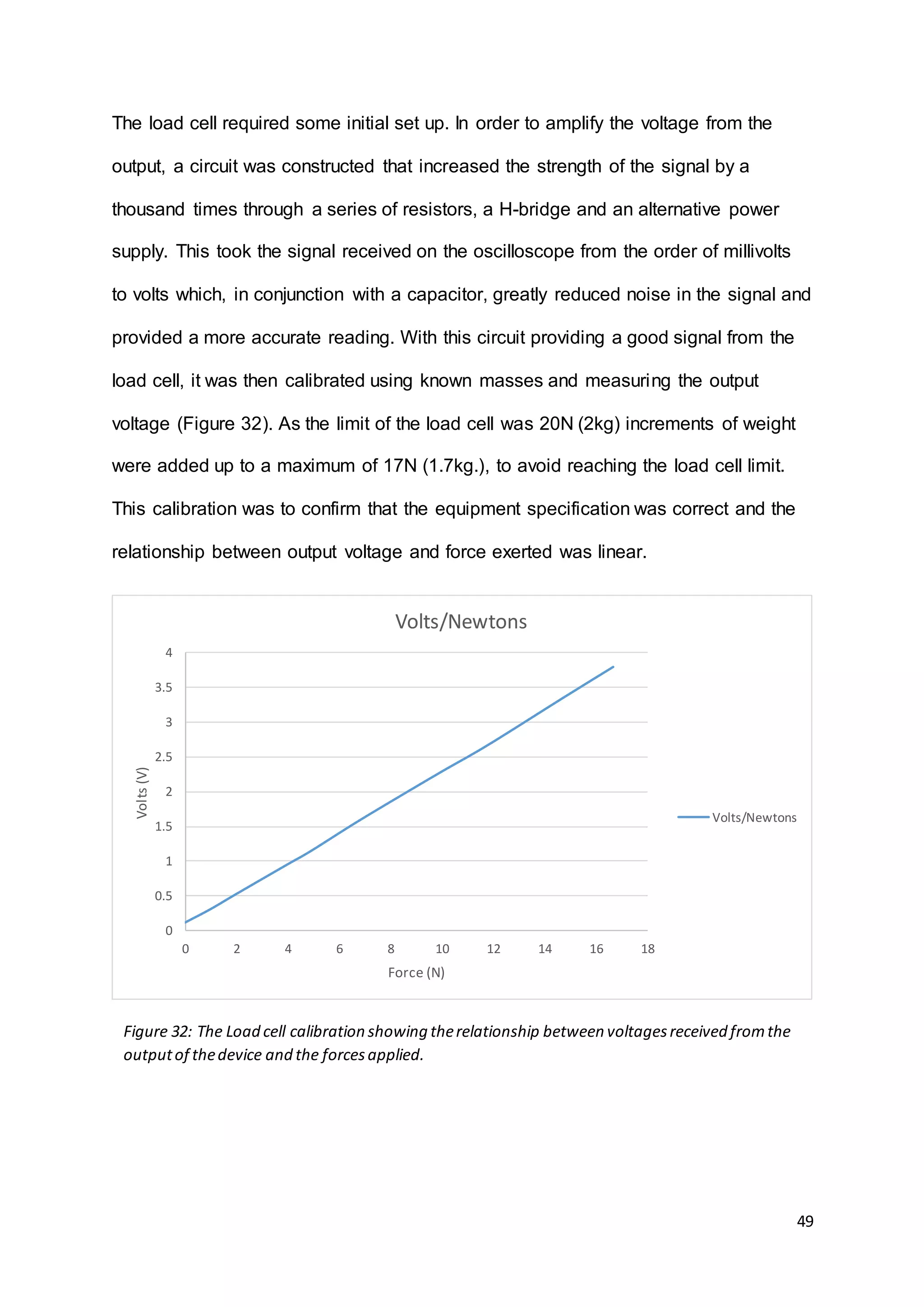

relatively small motor can drive its wings. The key feature of the Smartbird is the

active torsion designed into its wings. This consists of a servo mounted towards the

wing tip, on the outer most wing rib. This is connected to a microcontroller to

calculate the input from information drawn from an array of sensors for acceleration,

torsional force on the hand wing, and motor position. Data acquired from testing,

provides the relevant information in order to position the hand wings to twist into an

optimised position for the current flight conditions and phase of wing motion [3]. This

approach brings this design closer to its natural inspiration than any other design;

with it not only mechanically replicating the movement and motion of the bird’s

skeleton and muscles, but also replicating the bird’s sensory system by the various

on-board sensors. Festo has also undertaken other projects with flapping wings

drawing inspiration from dragonflies and butterflies in some of its other notable

Bionic Learning Network projects, known as the BionicOpter [4] and

eMotionButerflies [5].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-11-2048.jpg)

![12

5.1.2. Clear Flight Solutions: Robirds

Designed as a deterrent for nuisance birds around airports, waste and agricultural

sites [8], their manufacturer claims significant reductions in numbers of smaller birds

from repeated use in a given area [9]. However, they are not currently commercially

available and are still undergoing development. Unlike the Smartbird, the wings are

not articulated and do not contain servos to optimise twisting. They are however of a

flexible foam construction. A front and rear spar move to twist the chord of the wing

which provides lift and thrust. With regard to control, the Robirds do not have the

same aerodynamic turning effects with the tail and head moving together, however

enough manoeuvrability is still achieved for operation within an outdoor space.

Currently two types are being developed to replicate a peregrine falcon and an

eagle, which are still in the testing phase with an aim to make their flight completely

autonomous with an autopilot system. Perhaps not as technologically advanced as

the Smartbird, the Robirds do however have the speed to match their natural

equivalents, with a manufacturer’s claim of a 50mph top speed in the Falcon model

[10].

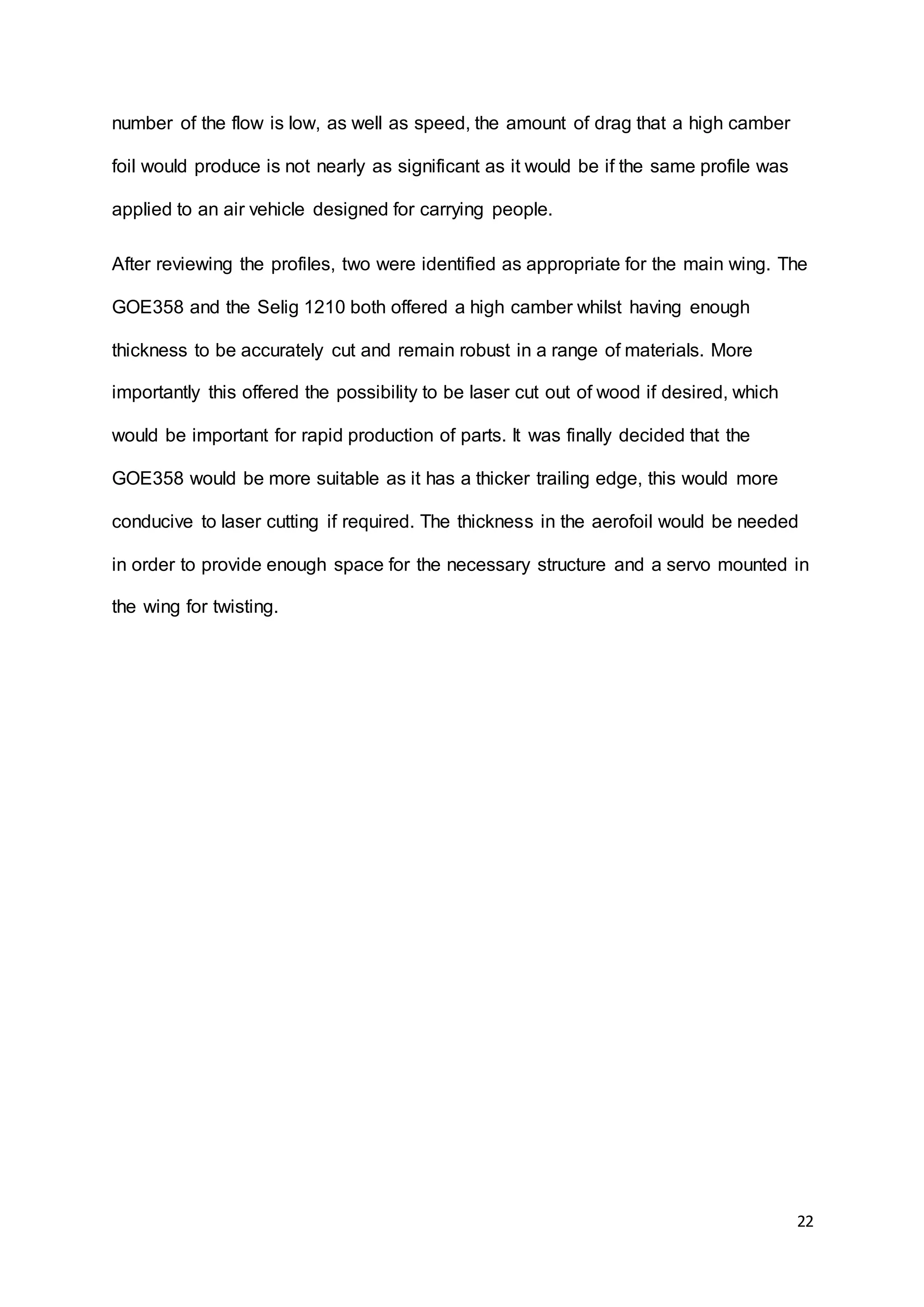

Figure 1: The Festo Smart bird [6] Figure 2: A CAD imageof the

Dragonfly inspired BionicOpter[7]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-12-2048.jpg)

![13

5.2. Bird Wing Profiles

Various attempts have been made to model bird wing profiles, however this proves

challenging in practice. A number of approaches have been tried, but due to the

nature of avian wings and their unique flexibility to suit a range of flight profiles, great

effort is required in order to obtain a profile for even one flight state. One initial

approach was to take measurements from museum specimens [11] and treat these

as fixed aerofoils rather than a highly deformable bird wing. However this method is

inaccurate due to the necessary process of preservation. Recently deceased

specimens [12] also experience problems in the uncertainty in what flight conditions

the wing was last set for. Even without these effects, errors would still occur as when

a bird is in flight, its sensory system is constantly optimising the wing through

differing flight stages [13]. Therefore the variables the wing experienced most

recently would be unidentifiable. Through this, the optimum method utilised is to

measure the wing whilst in flight. One such method by the Oxford department of

Zoology used a trained bird and photogrammetric techniques in order to pin

coordinates to points on the wing to model the inner surface. This was done by

setting up a series of six cameras around a known control volume containing a perch

on which the trained steppe eagle would land [14]. This meant measurements were

taken in a rapid pitch up manoeuvre from a shallow glide into a stall to land. Similar

work to this had already been undertaken, however this involved smaller birds in

Figure 3: The Clear flight solutions

Falcon model.The wing shapeplays

a large partin its successasa bird

deterrentwhich when flapping looks

similar to the real bird. [8]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-13-2048.jpg)

![14

wind tunnels with sparrow [15] and starling [16] test subjects. The use of smaller

birds provides little insight into Reynolds number regimes that would be experienced

by MAV’s built with current technology, as it is unlikely that a smaller bird species

could be replicated.

5.3. Bird Wing Anatomy

Although in many ways very different, the avian wing demonstrates numerous

similarities to the human arm [17]. Both in bone structure and the associated

muscles to drive movement. There are recognisable shoulder, arm and hand

sections to the bone structure, with the hand wing forming the significantly larger

area towards the tip of the wing containing the primaries [17] (primary feather group-

the largest feathers on the wing). The feathers attached to the arm wing are known

as the secondaries [17]. Unlike in a human arm, the arm wing in a bird accounts for

less than half of the total wing span. Other feather groups are known as the coverts

and the scapulars, with the coverts forming the feather covering of the leading edge

and the centre of the wing surface. Other notable similarities between birds and

humans is the presence of pectoral muscles used for flapping the wings down [18],

humans have similar muscles in the chest used to move their arms forward and

together.

Figure 4: The profiles thatresulted

fromthe photogrammetricstudy

undertaken by theOxford department

of zoology of a Malesteppe eaglein a

high pitch up manoeuvre.[14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-14-2048.jpg)

![15

5.4. Models For Flapping Wings

In order to design an optimised flapping wing MAV with the flight characteristics of a

real bird, the problem has to be numerically understood. Considerable work has

been done on the angle of attack, flap angle, and wing beat frequency, as well as

four unsteady mechanisms that frequently occur, and various other variables

associated with not only airflow but also a constant movement of the wings. Four

unsteady mechanisms cited frequently in literature are leading edge vortices, rapid

pitch up, wake capture and clap and fling [20]. These mechanisms are typical of

problems faced as they clearly aid in lift production in insects and birds but are

difficult to predict for variations with current methods of analysis. In further detail,

these models are described as follows:

5.4.1. Leading Edge vortex (LEV)

A flow of air created around the front of the wing which rolls over the leading edge

during the downstroke. The low pressure at the centre of the vortex creates a suction

force that attaches it to the wing during the stroke and increases the possible angle

of attack before stall is induced. This creates higher lift than is normally obtainable by

the same wing and enhances the performance of the wing over its capabilities in

Figure 5: the labelled arrangement

of featherson a bird wing. [19]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-15-2048.jpg)

![16

steady state flow. The vortex has been found by studies to be conical in shape,

having a smaller radius towards the root of the wing and much larger diameter at the

wing tip. This is due to the increases in the wings tangential flow velocity along the

span. This mechanism has been identified as the most significant in flapping wing

flight to increase the lift, however observations vary as to the LEV’s behaviour on

different wings. In some cases it is seen to be permanently attached, whereas in

other cases it sheds and reforms with each beat.

5.4.2. Rapid Pitch Up

A quick rotation at the end of each stroke, where the wing moves from a low to high

angle of attack, generating much higher lift coefficients than the steady state stall

value [20].

5.4.3. Wake Capture

Occurs as a wing travels through the wake it created on a previous wingbeat.

Research has shown peaks in aerodynamic force when the wake of a previous wing

beat is captured with correct phasing and twist of the wing [20].

5.4.4. Clap And Fling Mechanism

This refers to the way the set of wings are moved during the wingbeat. The majority

of birds do not use this type of motion in normal flight, however some, such as the

hummingbird could be described to use a clap and fling motion. More applicable to

insect flight, this model for wing movement describes the upward motion (the clap),

where the wing leading edges are clapped together at the end of the upstroke. The

downstroke consists of the leading edges moving apart whilst the trailing edge

remains stationary, therefore the wing rotates around the trailing edge. This is known

as the ‘fling’ [19].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-16-2048.jpg)

![17

5.5. Useful Equations

For the Numerical Analysis of the project there are some papers for work previously done

that provide good methods and equations that could be applied. These studies carried out

are notably those by Whitney J.P (2001) [22], and Dickinson M.H. (1999) [23]. Both provide

good relationships to be followed and good approximations of CL and CD to be applied to

flapping wings.

The Study by Whitney [22] focuses on conceptual design of MAV’s with no practical work

undertaken. A large focus of the paper is on the hovering energetics and predicting the flight

performance such as the range and speed of the vehicle. However, of interest to this project

is the work undertaken to predict the damping force and the relationship produced between

φ and α (Figure 7). This would be useful to predict the timing of the parameters of the test rig

wings and apply further calculations to obtain the wings lifting force as a function of the

theoretical angle of attack.

Figure 6: The clap and fling

mechanism,herethe diagramsare

shown asif looking fromabovethe

insect/ bird and the circular ends

representthe leading edge of the

aerofoil.[21]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-17-2048.jpg)

![18

The second study by Dickinson [23] produces approximations for CL and CD in flapping

wing applications (Figure 8). More importantly these are a function of α which due to the

planned servos in the wings, is easy to control. To obtain a theoretical lift force, these

equations can be applied to the predicted or actual α to find an approximation. The CL value

could then be used in conjunction with the lift equation in order to provide a predicted or

theoretical Lift Force.

𝐶𝐿 = 0.225 + 1.58sin(2.13𝛼 − 7.2)

𝐶𝐷 = 1.92 − 1.55cos(2.04𝛼 − 9.82)

𝐿 = 𝐶𝐿

𝜌𝑉2

2

𝐴

Figure 7: Top: J.P.

Whitney projectsthe

theoretical relationship

between φ and α n his

design.Moreof interest

is the phasing of both

sets of motion which

follow a sinusoidal

relationship.This timing

would be good to

replicate in the

experimentalsection of

the project.

Bottom:The plotof

damping forcewith α,

this is the force thatacts

againstthedriving

mechanism. [22]

Figure 8: The approximationsmadeby Dickinson in his workwith the Lift equation

presented below.With a way of measuring Density and velocity aswell as the angle of

attack,theseequationscould beapplied asin workby SaneS.P.[2] to the physicaldata

gathered fromthetest rig and compared to actual values.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-18-2048.jpg)

![19

5.6. Flexibility In Flapping Wings

When comparing wings of aircraft to those found in the natural world, one of the

main differences is the flexibility of bird and insect wings. Insects are typically

characterised with very thin transparent wings with an intricate vein structure to add

rigidity. Whereas bird’s wings consist mostly of feathers with a minority of the wing

surface area being taken up by the bone structure and muscular makeup necessary

for flapping. Feathers typically have a stiff spine to them however this is still not

completely rigid, which allows for a flexible wing. Although studies into natural flyers

initially focussed on defining wings as rigid, studies have now been undertaken to

determine the effects of flexibility.

It has been found that trailing edge flexibility has a considerable effect on the wing

aerodynamics. When a rigid wing translates at a high angle of attack, the leading

and trailing edge vortices periodically generate and shed as found in the results of

(Zhao, et al, 2010) [24]. A wing that has an optimised flexible trailing edge, however

can generate a smaller but much more stable leading edge vortex, with some

parameters out performing rigid wings when used in flapping configurations [24].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-19-2048.jpg)

![20

6. Chapter 1: Methods and Design

6.1. NumericalModelling

Before designing a test rig and wing structure, a numerical analysis of the problem

had to be made. This would provide an indication of the forces acting on the wing. It

was necessary to make calculations, as a critical element to designing a vehicle with

flapping wings would be the lift and thrust achieved, compared to the weight. An

initial estimate for a vehicle weight of 400g was made based on weights of the

notable projects studied in the literature review, most specifically the Festo Smartbird

was considered due to a wealth of information available [3]. With this estimation in

place, the task was to produce a wing and carry out appropriate sizing to produce

adequate lift to support the vehicle in flight. Initial work involved research into

aerofoils, which led into a determination of the Reynolds flow regime the wing would

operate in, this would then be used in XFLR5 to provide results with greater

relevance to a vehicle of the design size. Further theoretical work then required

calculations for resultant flow velocities to find the velocity of induced flow due by

flapping of the wings. This could then be used in XFLR5 to attempt to estimate for lift

force achieved by the test rig at a specific flapping frequency and Angle of Attack

during strokes.

6.1.1. Aerofoil Selection

When selecting a profile for the wing, several considerations had to be made. Firstly

as the project would draw inspiration from biological applications, the profile of the

wing should reflect that of those found in the natural world. Secondly, there would

not be the time or the need for developing a profile unique to the project as a large

variety of aerofoil shapes are readily available for public use. Another consideration](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-20-2048.jpg)

![21

would be the strength of material the sections would be constructed from and

tolerances involved with cutting the wing ribs to that profile. These limitations and

criteria required considerable research in order to ensure the right profile was

chosen.

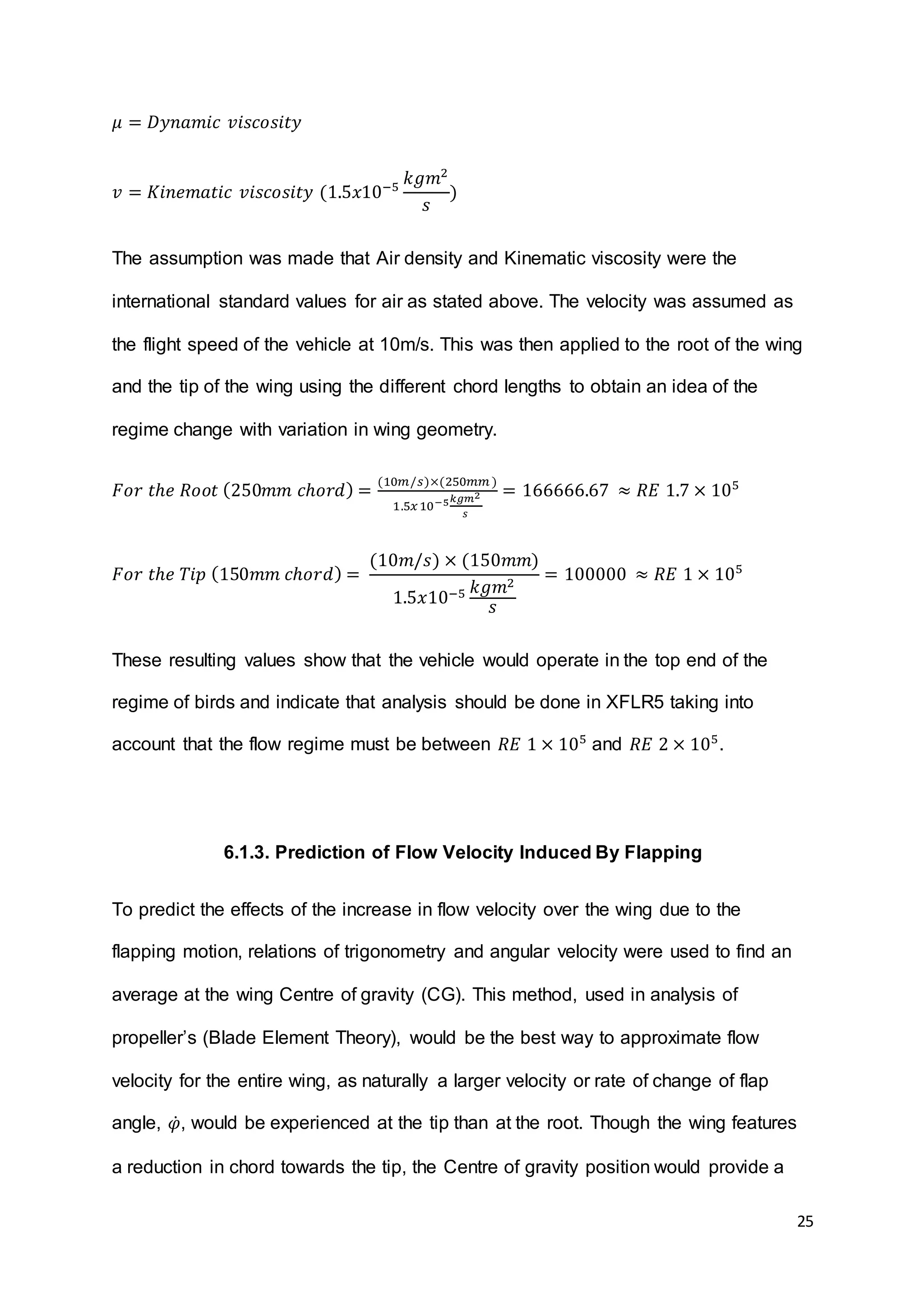

To better understand the characteristics of a bird wing aerofoil, the literature review

aimed to investigate papers where work had been done to obtain a cross section of a

bird wing in flight. The oxford department of zoology [14] achieved this successfully

using a series of cameras around a control volume to obtain an accurate model for

the inner wing of a trained eagle. The result of this study is shown below in Figure 9.

With these findings it was realised that the profile needed to be highly cambered and

have a large leading edge radius and thin trailing edge to correctly replicate the

natural wing. It would also be desirable for the aerofoil to be designed for Low

Reynolds number flow, as based on the vehicles dimensions, it would be expected to

operate somewhere between 𝑅𝐸 1 × 105

and 𝑅𝐸 2 × 105

.

After a search to find a selection of profiles that fitted the already mentioned criteria,

possible candidates were those shown in Figure 10. All aerofoils in this selection are

for Low Reynolds flow, and are highly cambered. The high camber is essential as

the vehicle is operating at low speeds in comparison to conventional aircraft, an

aerofoil with low camber would likely not generate enough lift. As the Reynolds

Figure 9: Aerofoil profiles obtained by

the oxford department of zoology. This

provided a good foundation for the

characteristics to look for in bird-like

aerofoils. [14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-21-2048.jpg)

![23

6.1.2. Determining Reynolds Number of The Flow Regime

For varying sizes of airborne vehicles, the flow regime that they experience changes.

This is measured by the Reynolds number of the flow. Commercial jets fly in the

regime of 𝑅𝐸 1 × 107

which is considered as high, birds and insects on the other

hand operate at 𝑅𝐸 1 × 103

− 𝑅𝐸 1 × 105

, with insects towards the bottom of the

scale and large birds at the top (Figure 11). Major work in the lower Reynolds

Figure 10: The aerofoil profiles considered for

the design. (1. FX60-100 10%, 2. GM15, 3.

GOE368, 4. GOE63, 5. GOE358, 6. Selig 1210

12%, 7. GOE500) [25]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-23-2048.jpg)

![24

regimes has come about in recent times with the interest in Micro-Air Vehicles, small

unmanned aircraft similar in size to large birds do not experience the same effects as

a large aircraft and must be designed differently.

The flow regime can be determined by using the equation stated below which takes

into account the chord of the wing, and velocity of flight.

𝑅𝐸 =

𝜌𝑉𝑙

𝜇

=

𝑉𝑙

𝑣

Where:

𝑅𝐸 = 𝑅𝑒𝑦𝑛𝑜𝑙𝑑𝑠 𝑛𝑢𝑚𝑏𝑒𝑟

𝑉 = 𝑣𝑒𝑙𝑜𝑐𝑖𝑡𝑦

𝑙 = 𝑐ℎ𝑜𝑟𝑑

𝜌 = 𝐴𝑖𝑟 𝐷𝑒𝑛𝑠𝑖𝑡𝑦 (1.225

𝑘𝑔

𝑚3

)

Figure 11: A plot showing theReynoldsnumberagainstthespeed of airborne

body.Thisshowshowvariousapplicationscompare[26].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-24-2048.jpg)

![28

Where 𝑟𝐶𝐺 is the distance of the wing span from the hinge to the wing CG.

With the values calculated it is possible to calculate the peak resultant flow velocity

over the wing by using the components of the downward or upward movement of the

wing CG and the free stream flow velocity. These calculations are identical to those

carried out for Blade element theory on aircraft propellers [27], this relies on the

simple trigonometry of an aerofoil moving at a constant velocity, perpendicular to a

freestream velocity generated by the flight speed on the vehicle. This in turn would

produce a resultant effective velocity acting at an angle offset to the freestream.

Although some previous studies have omitted these calculations, many were for

smaller insect like wings. Due to the span of the test rig wings it was felt that the

velocity induced by the wings through their fastest point at the horizontal position

may be significant. This peak velocity could have an effect on the peak lifting force

generated by the wings. This is of interest in this study as the peak force achieved

would give an indication into the feasibility of the concept being adapted to a flying

vehicle. In Figure 14 the components of the resultant velocity are shown.

Figure 14: A diagramto showtherelative direction of flow velocities acting

on the wing [28].

𝑉∞

WingCG

𝑉𝐶𝐺 𝑀𝐴𝑋

𝑉𝐶𝐺 𝑀𝐴𝑋

𝑉𝑅𝐸𝑆

Where:

𝑉∞: Free StreamVelocity

𝑉𝐶𝐺 𝑀𝐴𝑋

: Vertical Velocityof WingCG

𝑉𝑅𝐸𝑆: ResultantVelocity

𝛼 𝑅𝐸𝑆: Angle of the Resultantvelocity

fromthe free stream

𝛼 𝑅𝐸𝑆](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-28-2048.jpg)

![29

In order to obtain the resultant flow velocity over the wing and its resultant angle, it

was simply a matter of applying Pythagoras, using a given velocity of the freestream,

and trigonometry to find its angle. Below calculations would provide the final inputs

for XFLR5.

𝑉𝑅𝐸𝑆 = √ 𝑉∞

2

+ 𝜑̇ 𝑀𝐴𝑋

2

And

𝛼 𝑅𝐸𝑆 = sin−1

(

𝜑̇

𝑉𝑅𝐸𝑆

)

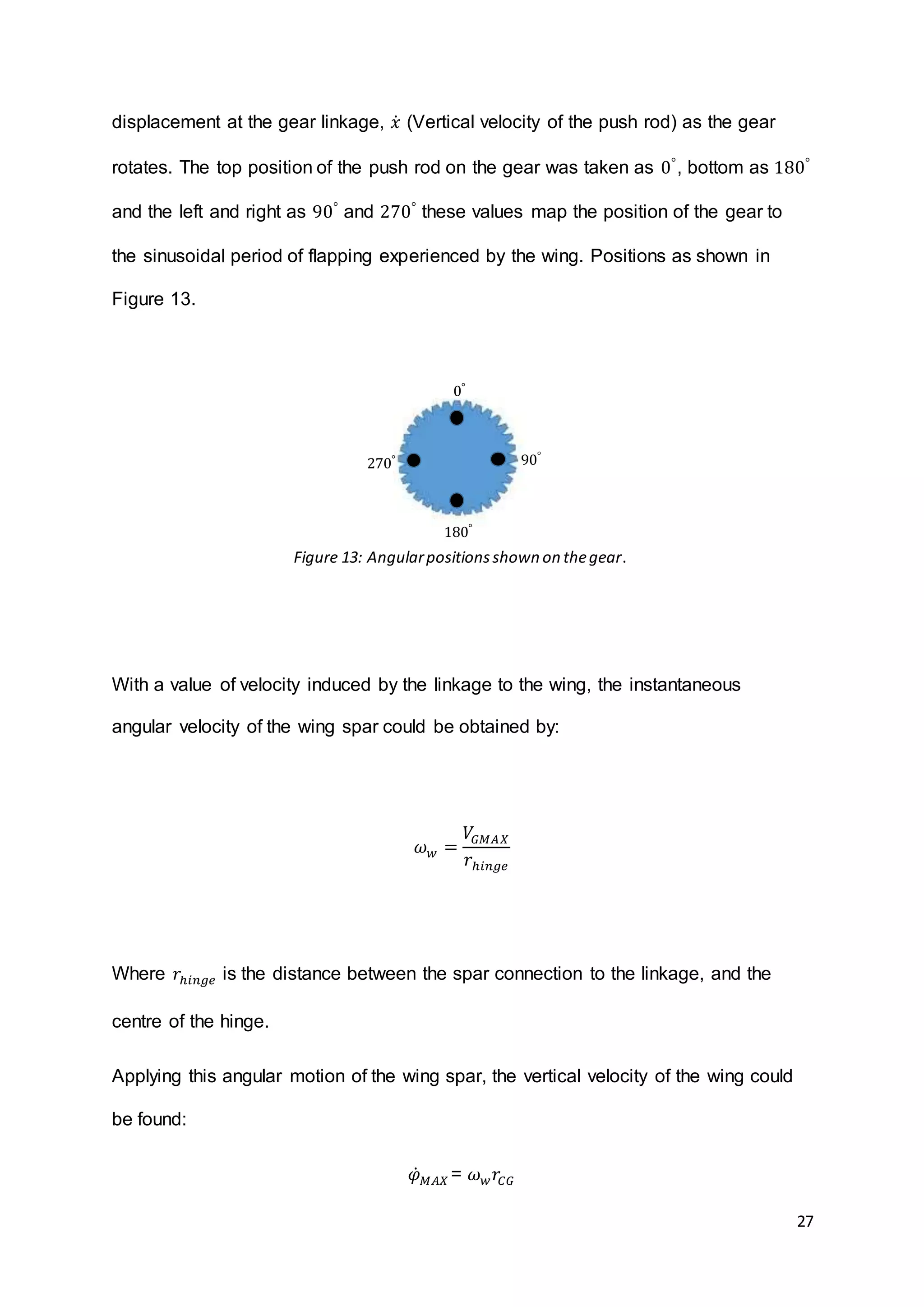

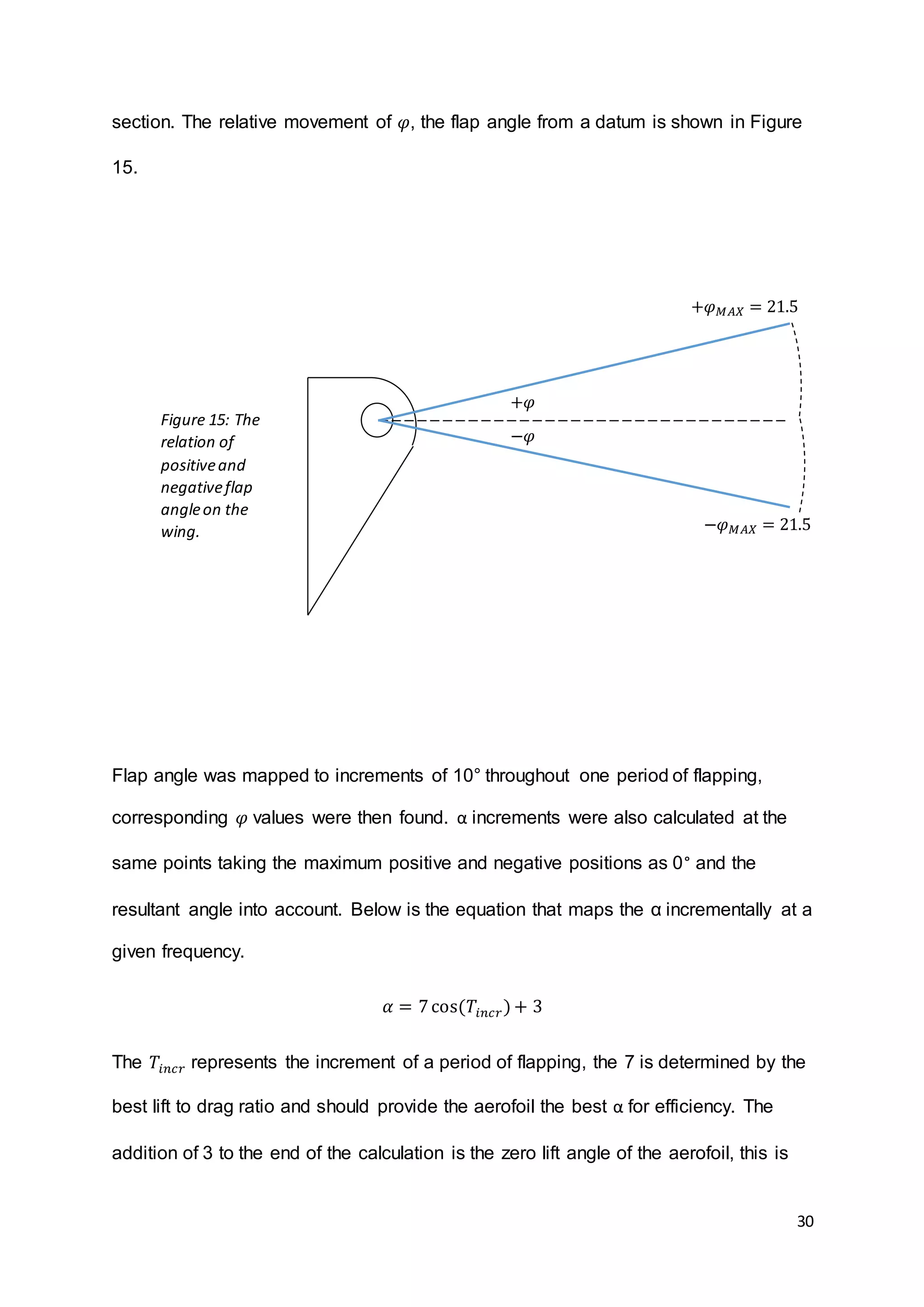

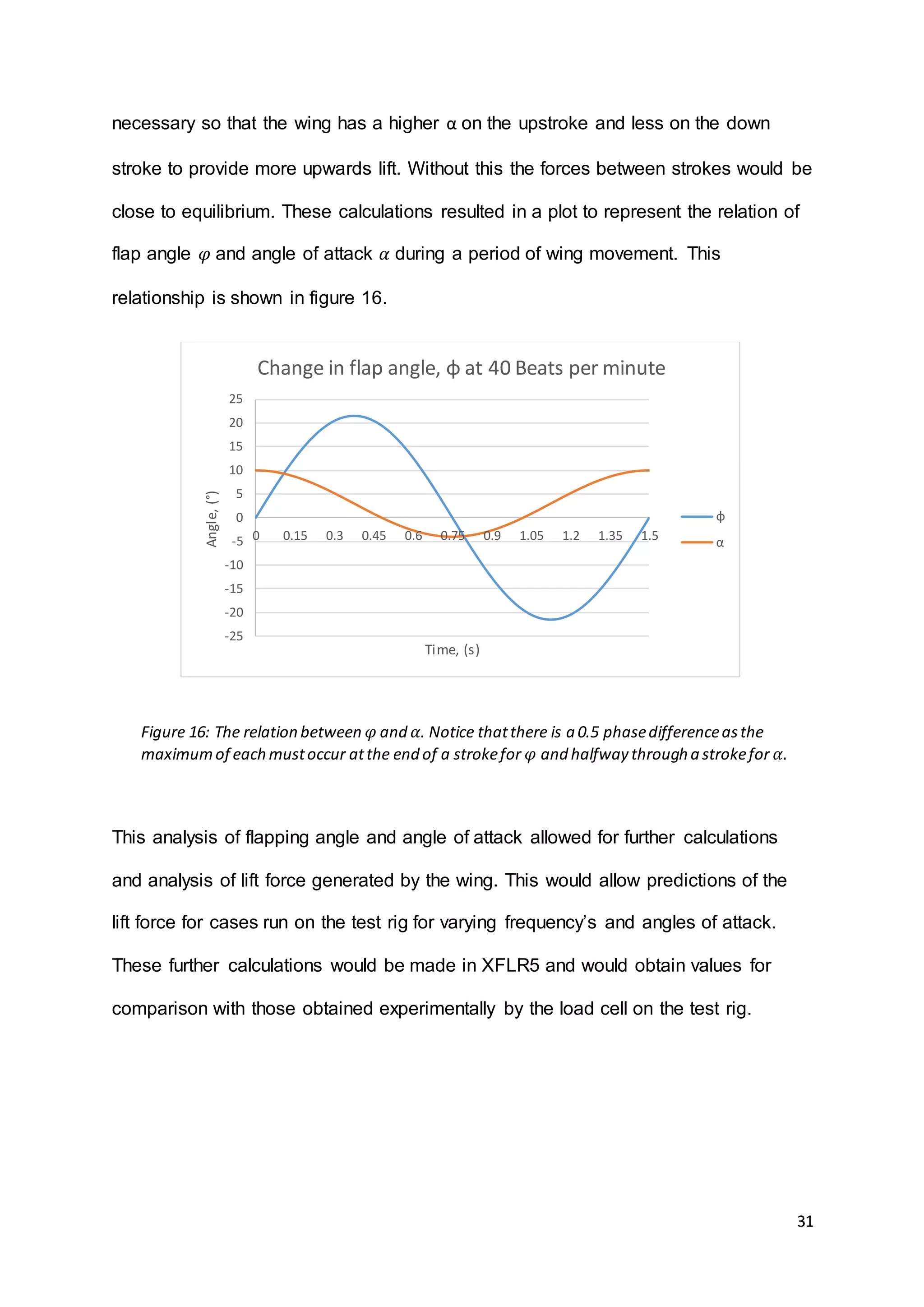

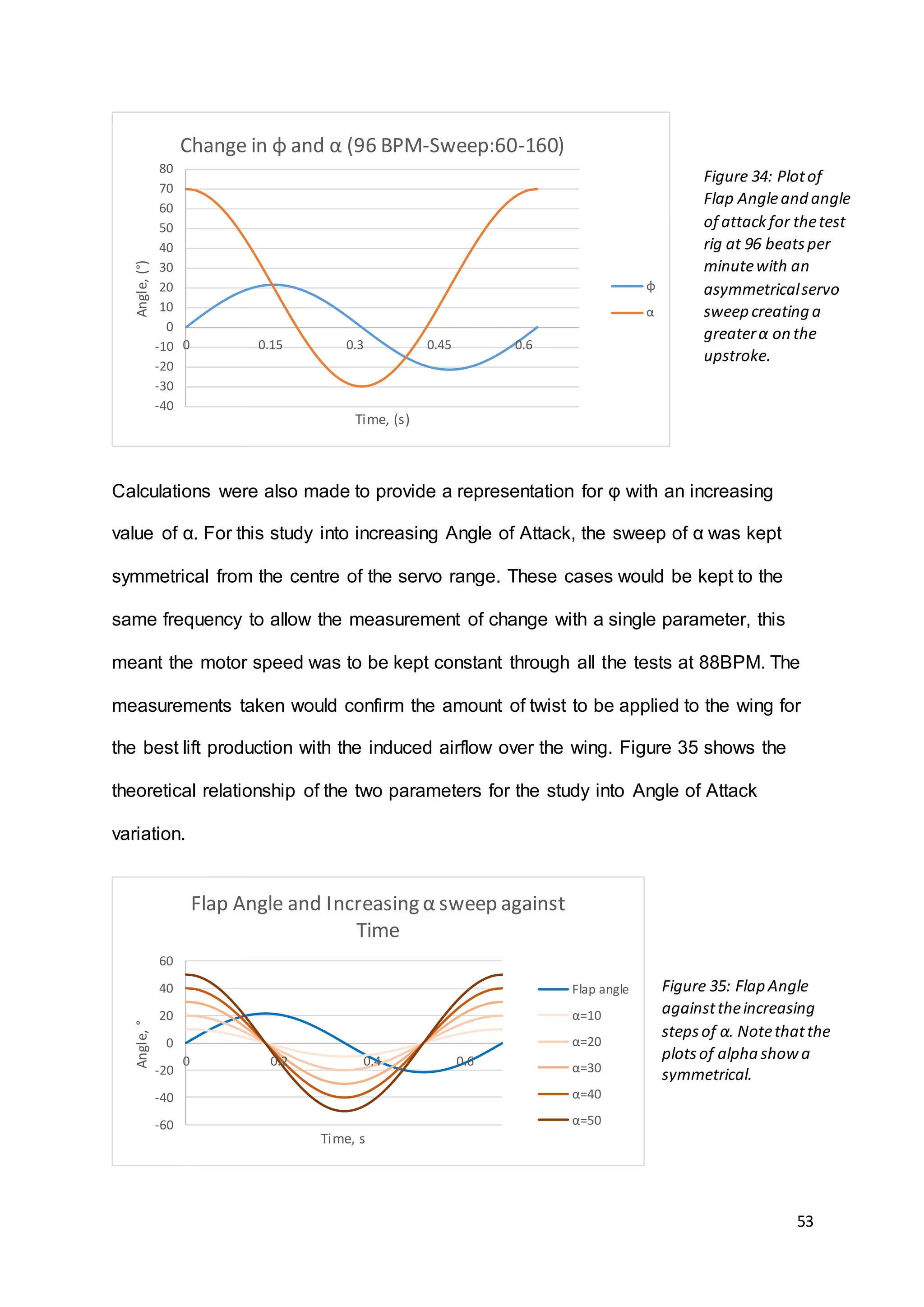

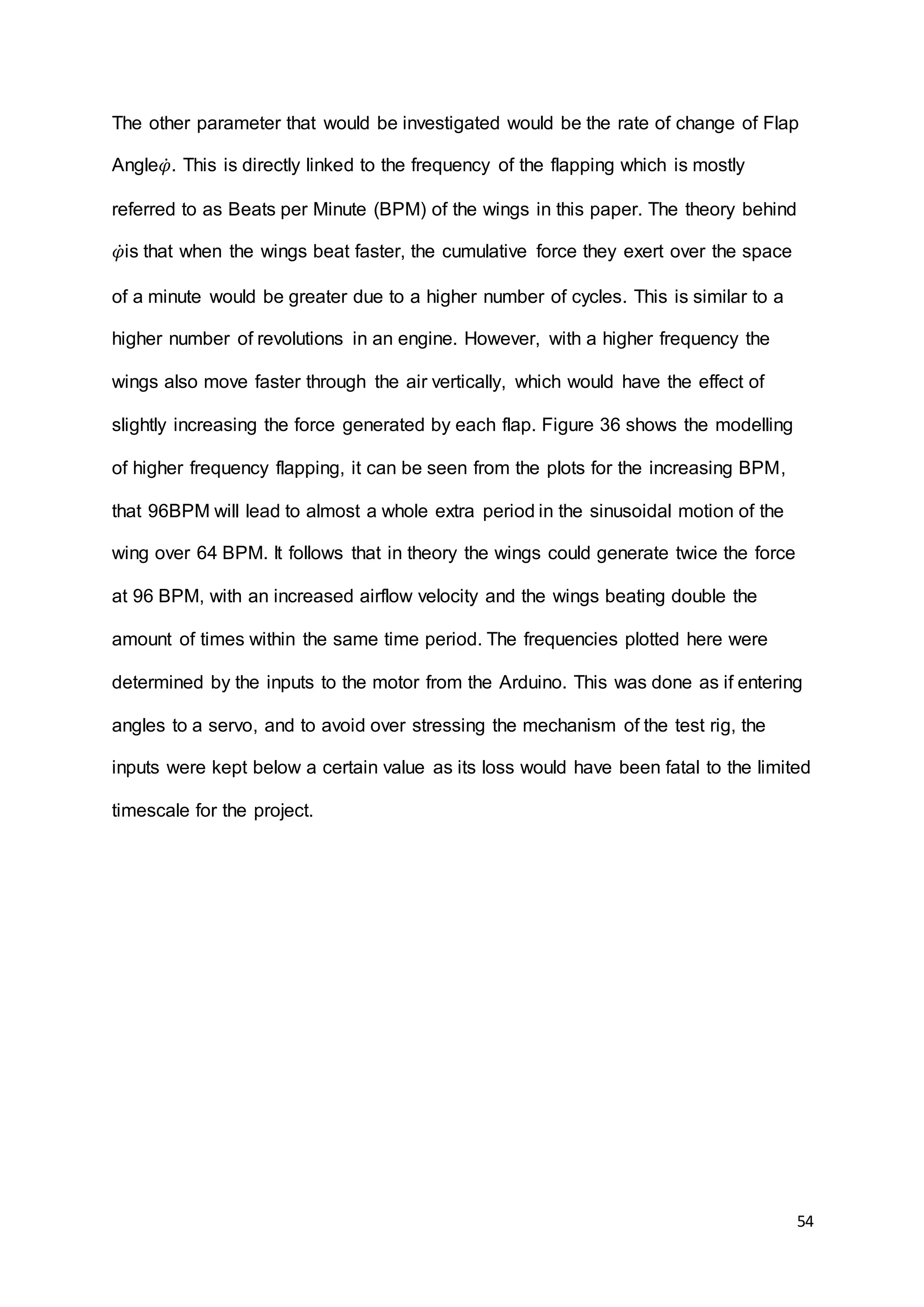

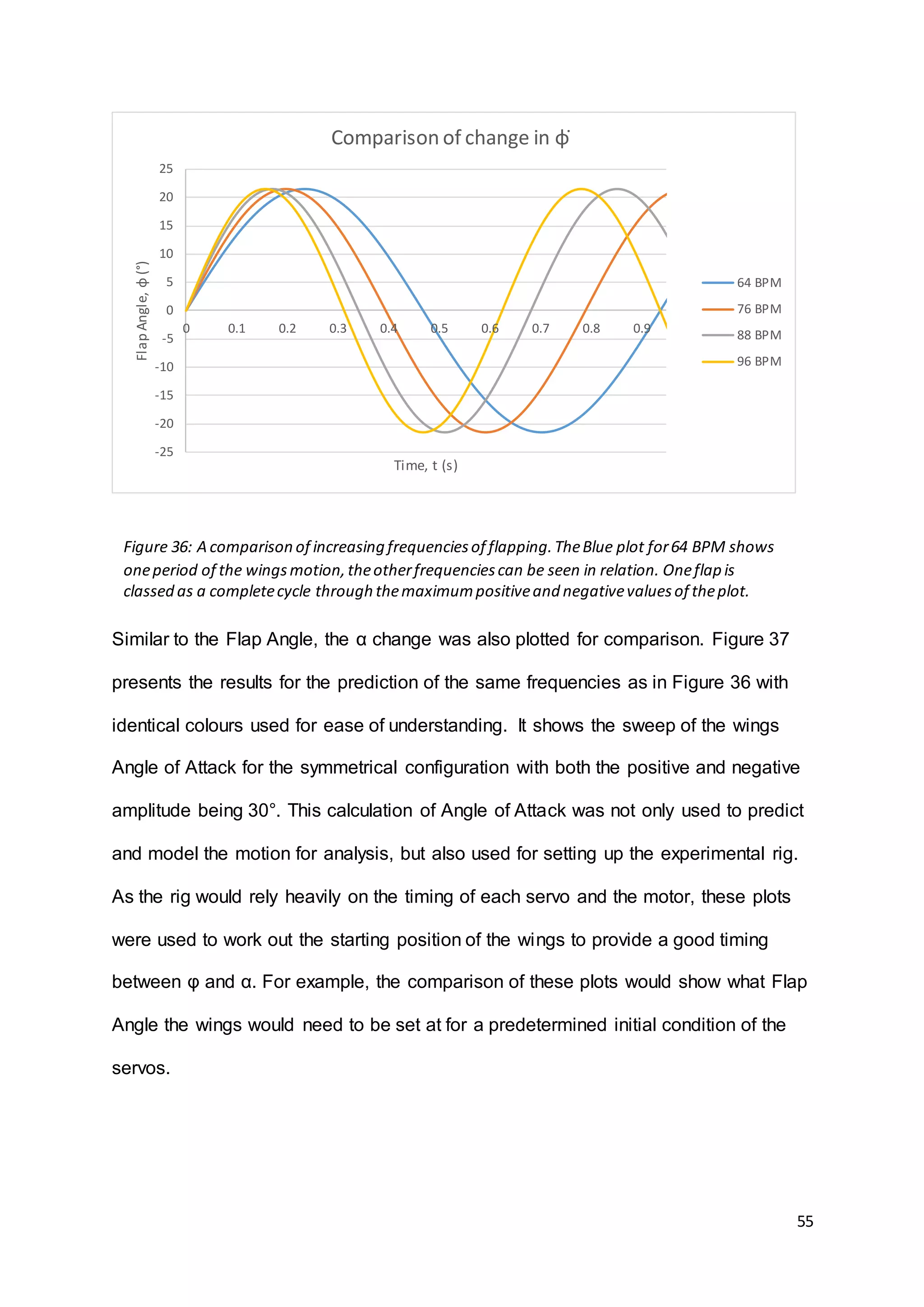

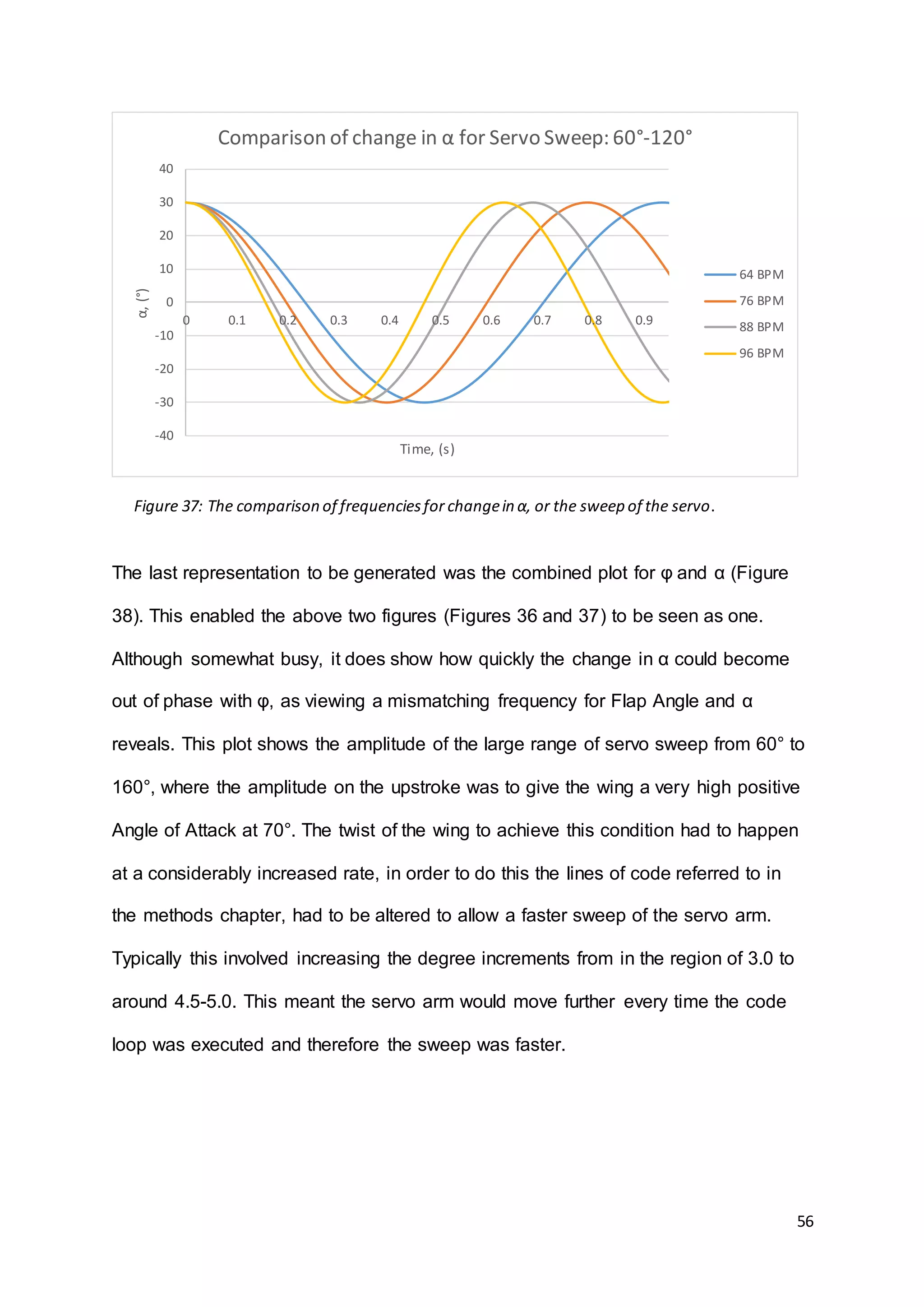

6.1.4. Equations Of Wing Flapping Motion

Having calculated some important elements of flow over the wing, it was also

necessary to determine and plot further characteristics. Using work done by Whitney

and Wood (2011) [22], the relationship between flap angle and alpha through one

period of flapping was calculated for various cases. Particularly the relationship

between flap angle and alpha would be useful as this would need to be recreated in

the control of the flapping motor and the servos for wing twist. The damping force

would also be important as if this was too great, the mechanism and motor would not

be able to withstand and overcome it to drive the wings. Flapping angle when

considered in the context of this study, is the angle of displacement of the wing from

the central datum of its range of movement.

Predominantly used were the equations derived in Whitney and Wood’s conceptual

model for instantaneous lift and damping force. Plots were also created for the

calculated change in flap angle, found by taking the 𝑉𝐶𝐺 𝑀 𝐴𝑋

discussed in the previous](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-29-2048.jpg)

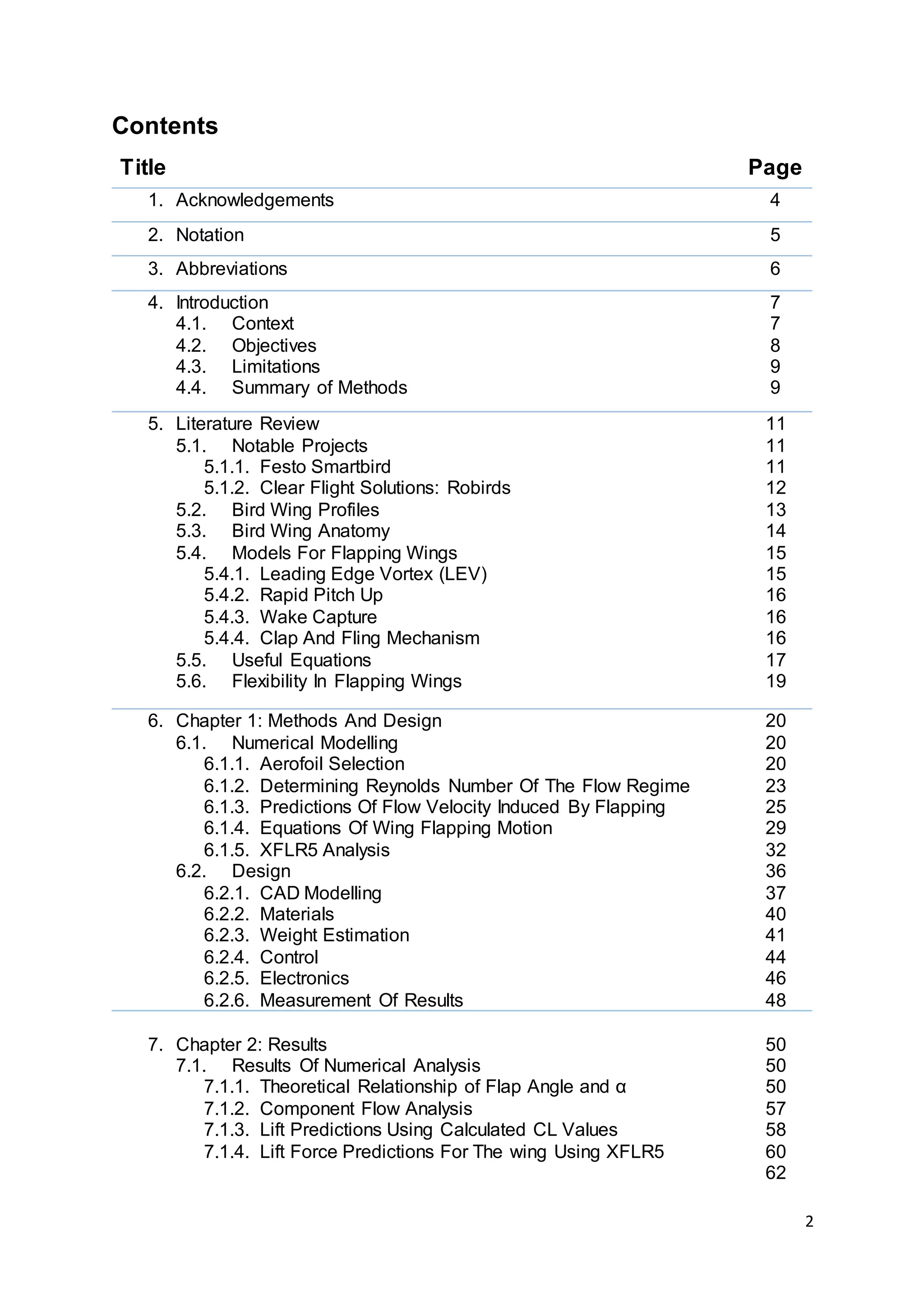

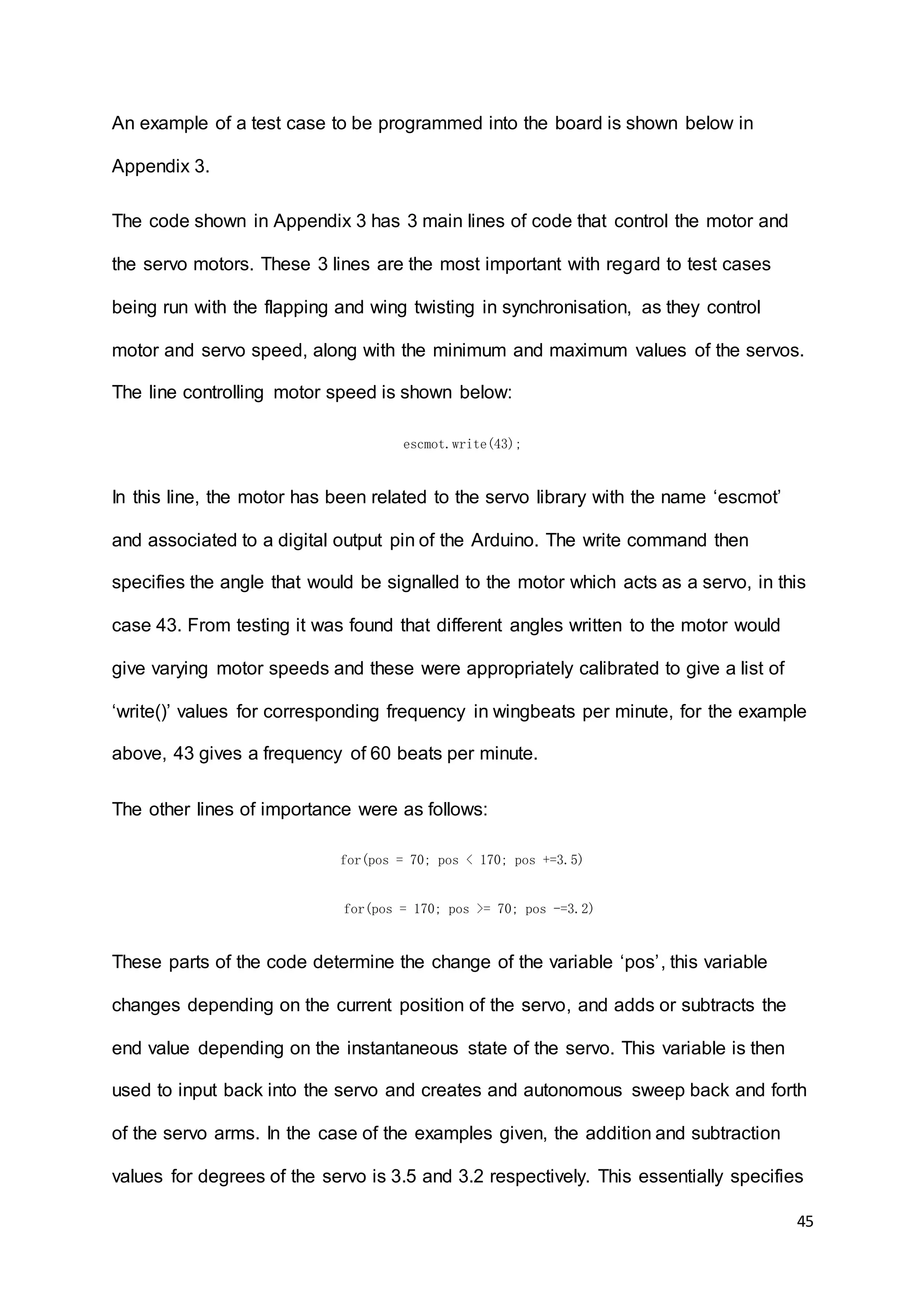

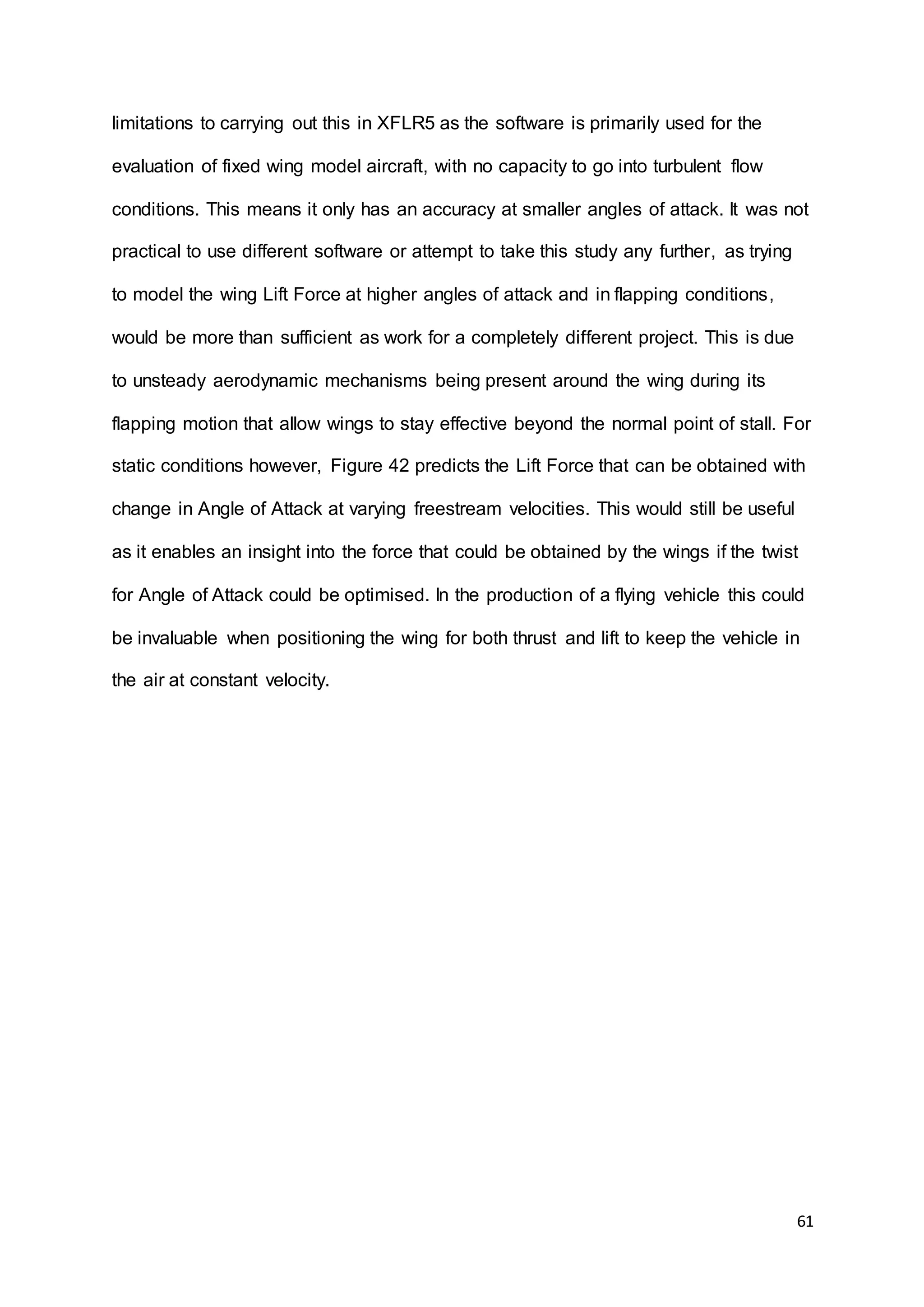

![57

7.1.2. Component Flow Analysis

Applying the basic trigonometry for blade element theory, it was possible to predict

the effective angle of the flow felt by the wing [27]. Presented here in the results is

simply this resultant angle. It was found that as the free stream flow increased, the

angle of the resultant becomes increasingly smaller as can be seen in Figure 39.

These results prove the theory that in ‘zero’ velocity conditions, the test rig high

Angle of Attack on the upstroke would be important, especially at higher frequency.

Due to the low velocity which can be seen as the 1m/s line in Figure 39, we can see

the movement of the wing creates a large angle between the datum for the

freestream and the effective flow compared to faster flight speeds. This result would

also suggest that the test rig might benefit from further studies being carried out in a

wind tunnel, or some other form of freestream flow if future studies were to be made.

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

Angle(°)

Time, s

Relation between andφ and α for varying frequency (60-160)

64 BPM (Flap angle)

64 BPM (Alpha)

76 BPM (Flap angle)

76 BPM (Alpha)

88 BPM (Flap Angle)

88 BPM (Alpha)

96 BPM (Flap Angle)

96 BPM (Alpha)

Figure 38: A combined plot of φ and α fora rangeof -30° to +70° of wing twist.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-57-2048.jpg)

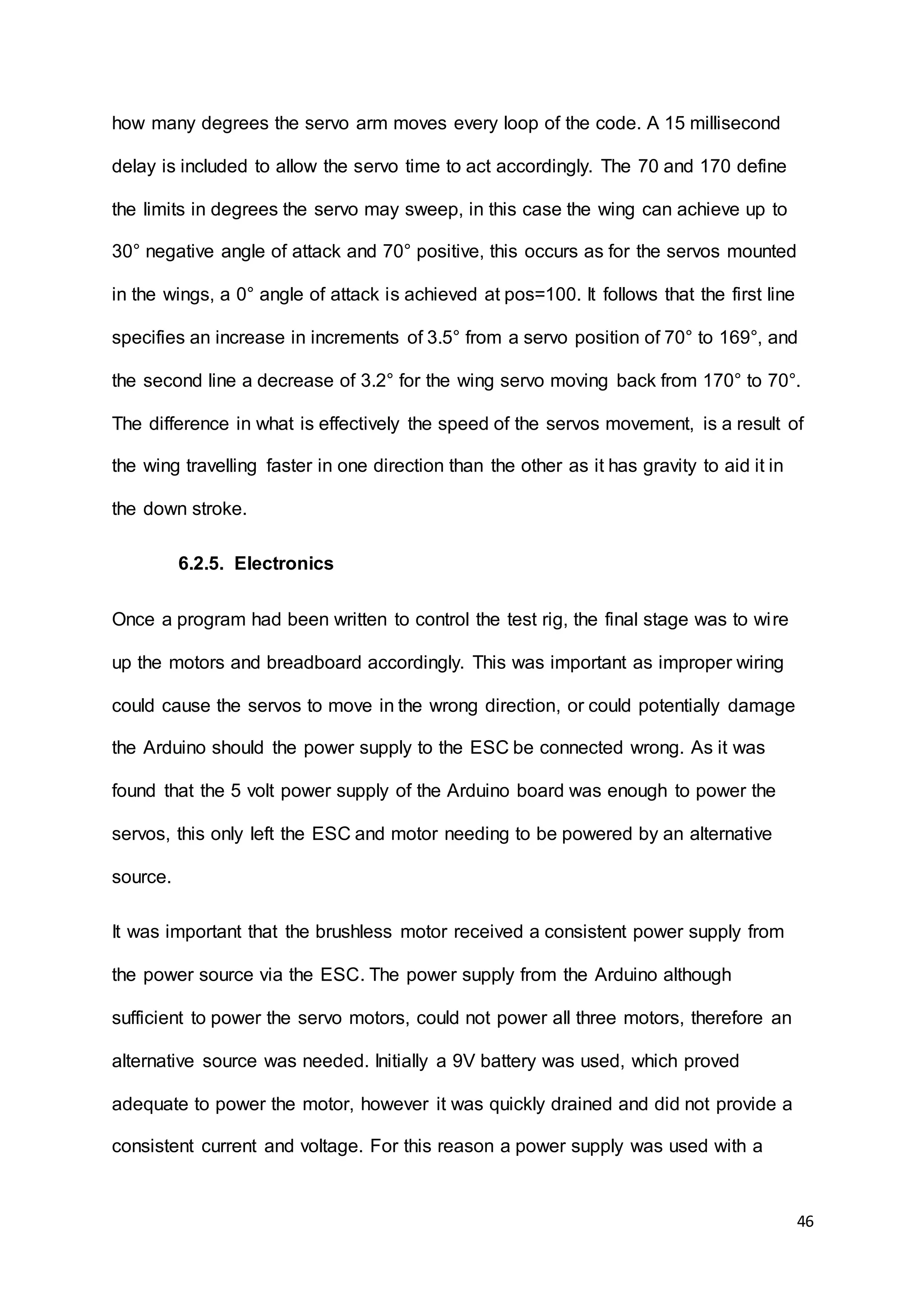

![58

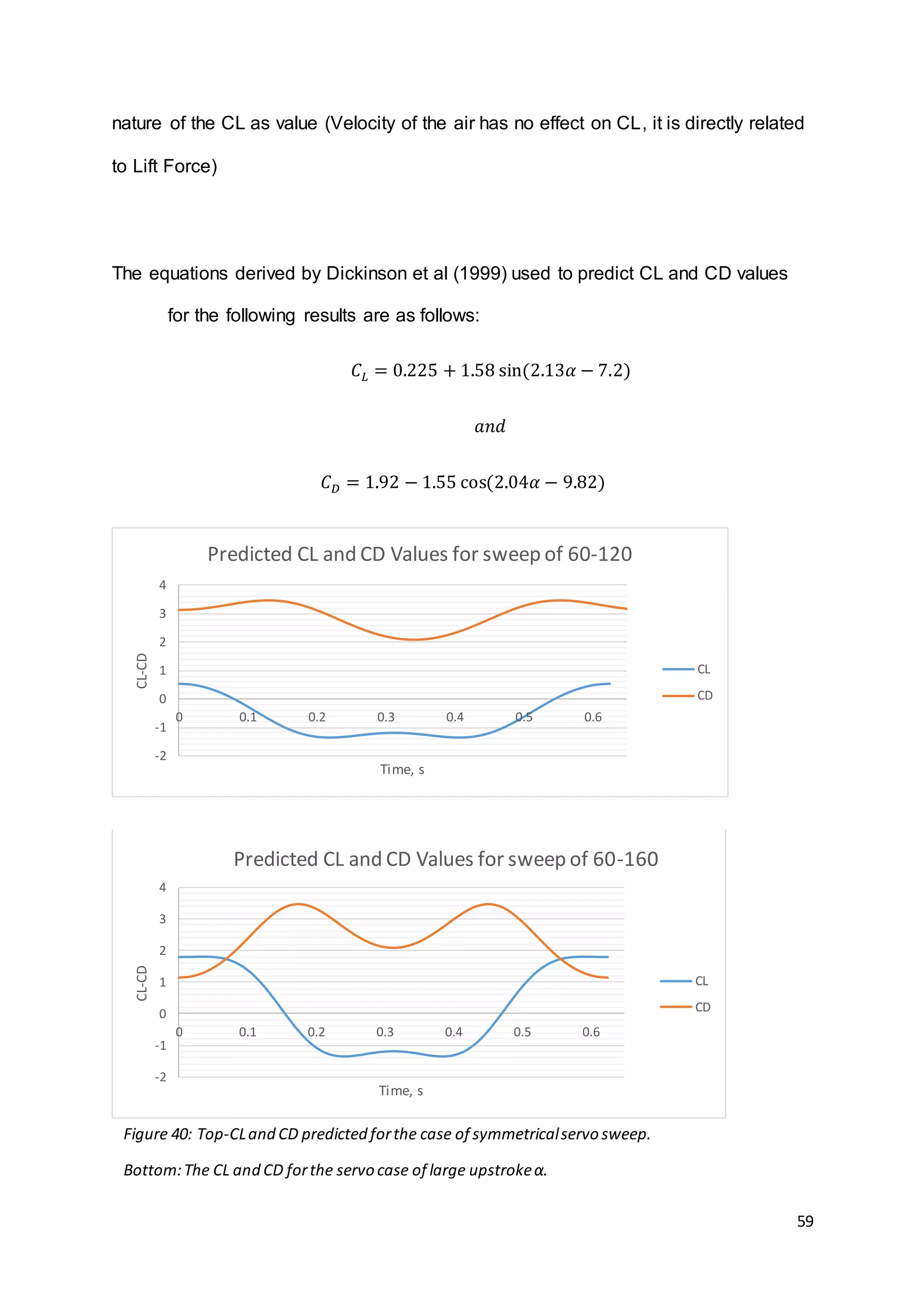

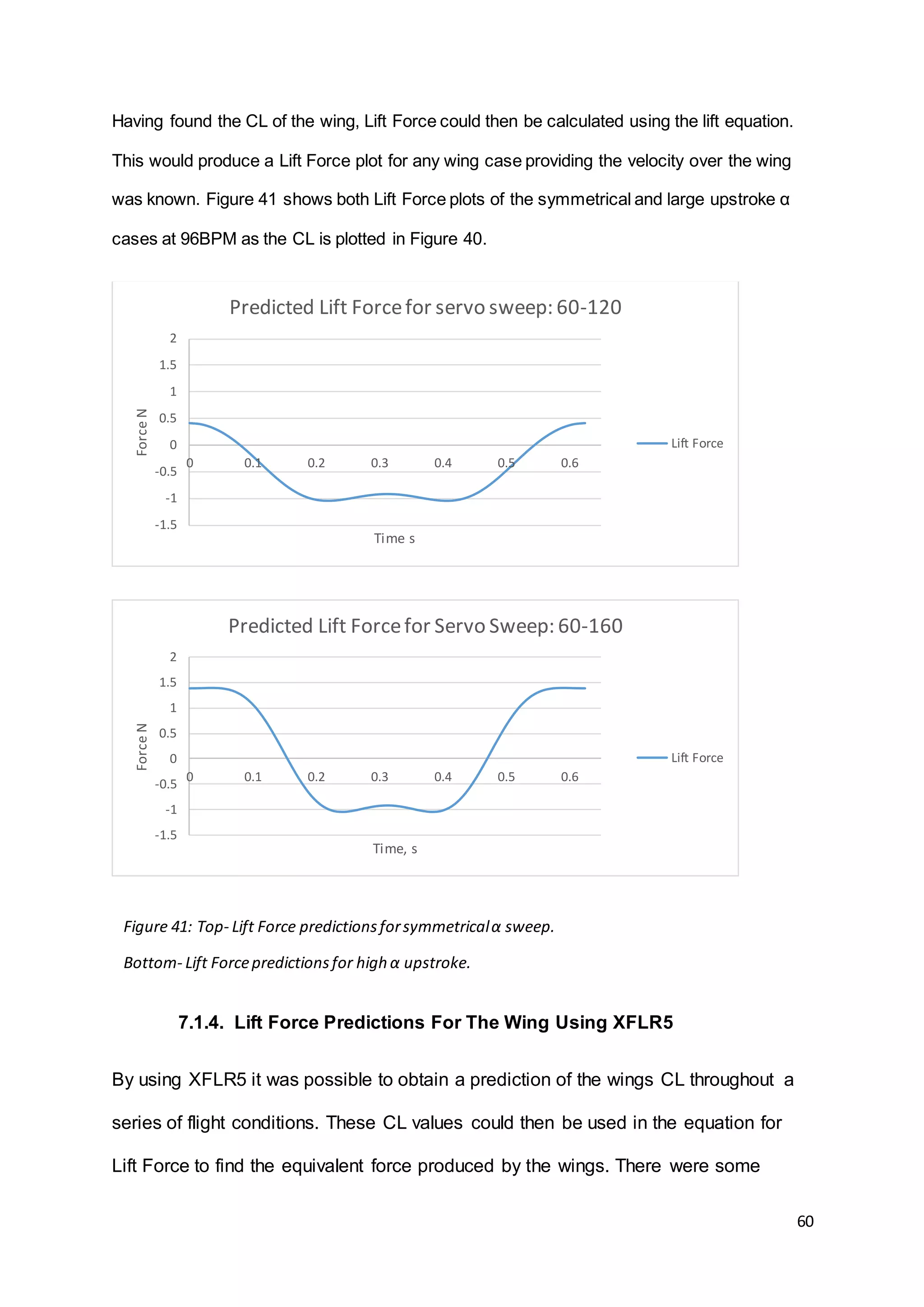

7.1.3. Lift Predictions Using Calculated CL Values

Using the method outlined by Sane and Dickinson (2001) [2] for their experimental

results, the same approach was taken with the calculated theoretical values obtained

for φ and α. This involved using equations derived by Dickinson et al (1999) [23] for

the approximation of CL and CD in flapping wings. Using this method, a separate

estimate of lifting force could be obtained to those found in XFLR5. Both approaches

would have their short comings, however both would provide results for comparison

to test results achieved. Figure 40 details the values found for both CL and CD for

both cases of the symmetrical ±30° α wing sweep, and the case of the wing having a

high α on the upstroke. These values would remain constant for any frequency (Also

the timescale plotted) over one period of the wings sinusoidal motion, due to the

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

5 15 25 35 45 55 65 75 85

Degrees°

Beats per Minute BPM

Beats per minute vs Resultant componentof flow over

wing.

@ 1 m/s

@ 2 m/s

@ 3 m/s

@ 4 m/s

@ 5 m/s

@ 6 m/s

@ 7 m/s

@ 8 m/s

@ 9 m/s

@ 10 m/s

Figure 39: The plotof theresultantflow anglestudy.Here theresultantα is shown on the

y axisagainstthebeatsper minute frequency of thewingsforvarying speedsof

freestreamflow.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-58-2048.jpg)

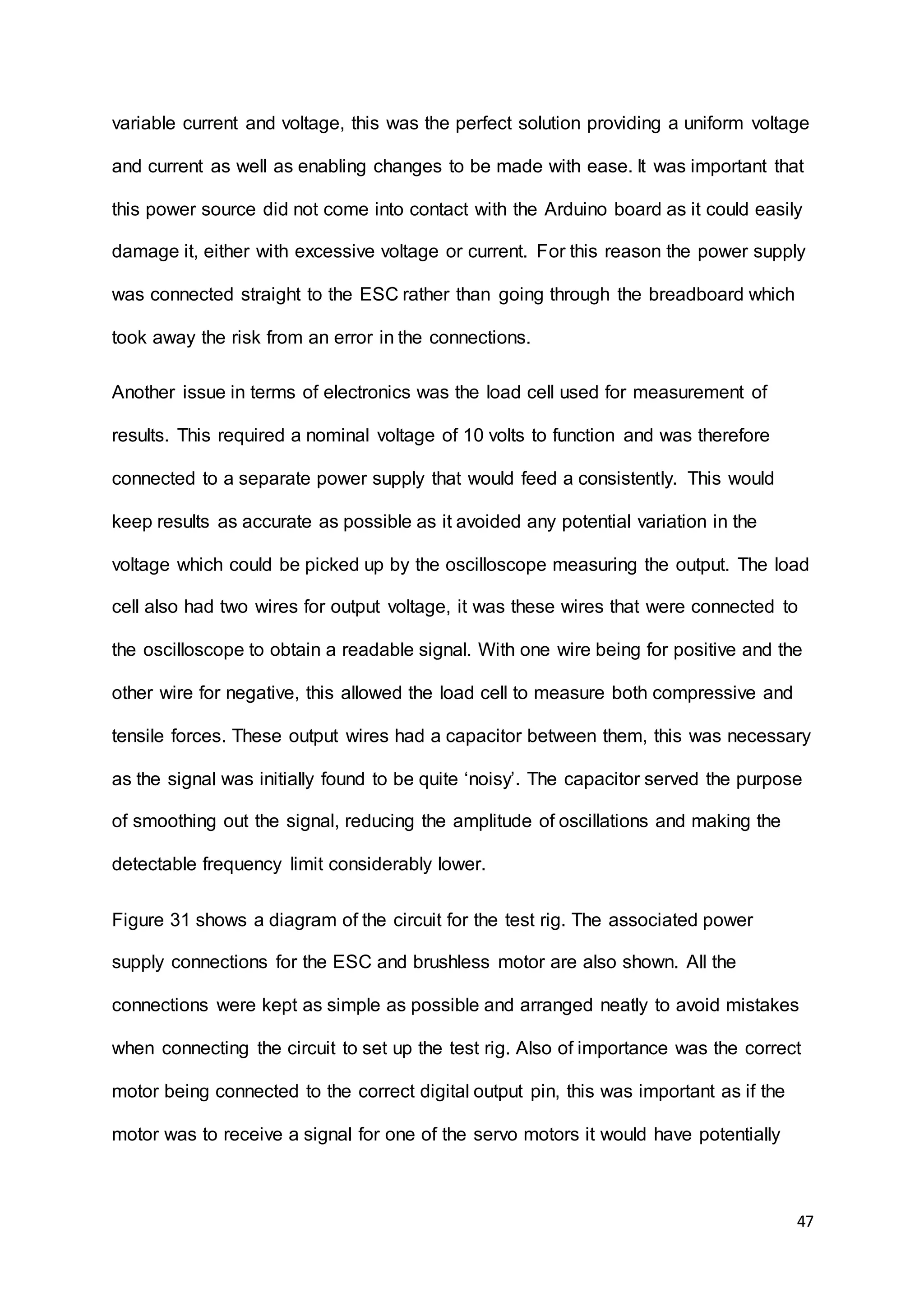

![65

7.2. ExperimentalResults

The results obtained from the load cell on the test rig were the product of a snapshot

taken from the oscilloscope screen. This meant that the results initially covered a

series of flap cycles and still contained some noise, even though capacitors had

been added to the circuit across the output leads to quieten the signal. An example

of a screen shot from the oscilloscope can be seen in Figure 46 with Figure 47 being

a plot of the force obtained after initial averaging and manipulation of the raw

numerical data. It would not be useful to analyse the results of multiple wing flaps as

some inconsistency could be found, it would also be hard to compare the large

amount of data generated over two cases. Because of this it was decided that the

best approach was that of Sane and Dickinson (2001) [2], where the average of

multiple wing strokes was taken to provide data for just a single wingbeat. This would

lead to any anomalies being lost into a data set for a single wing beat of averages.

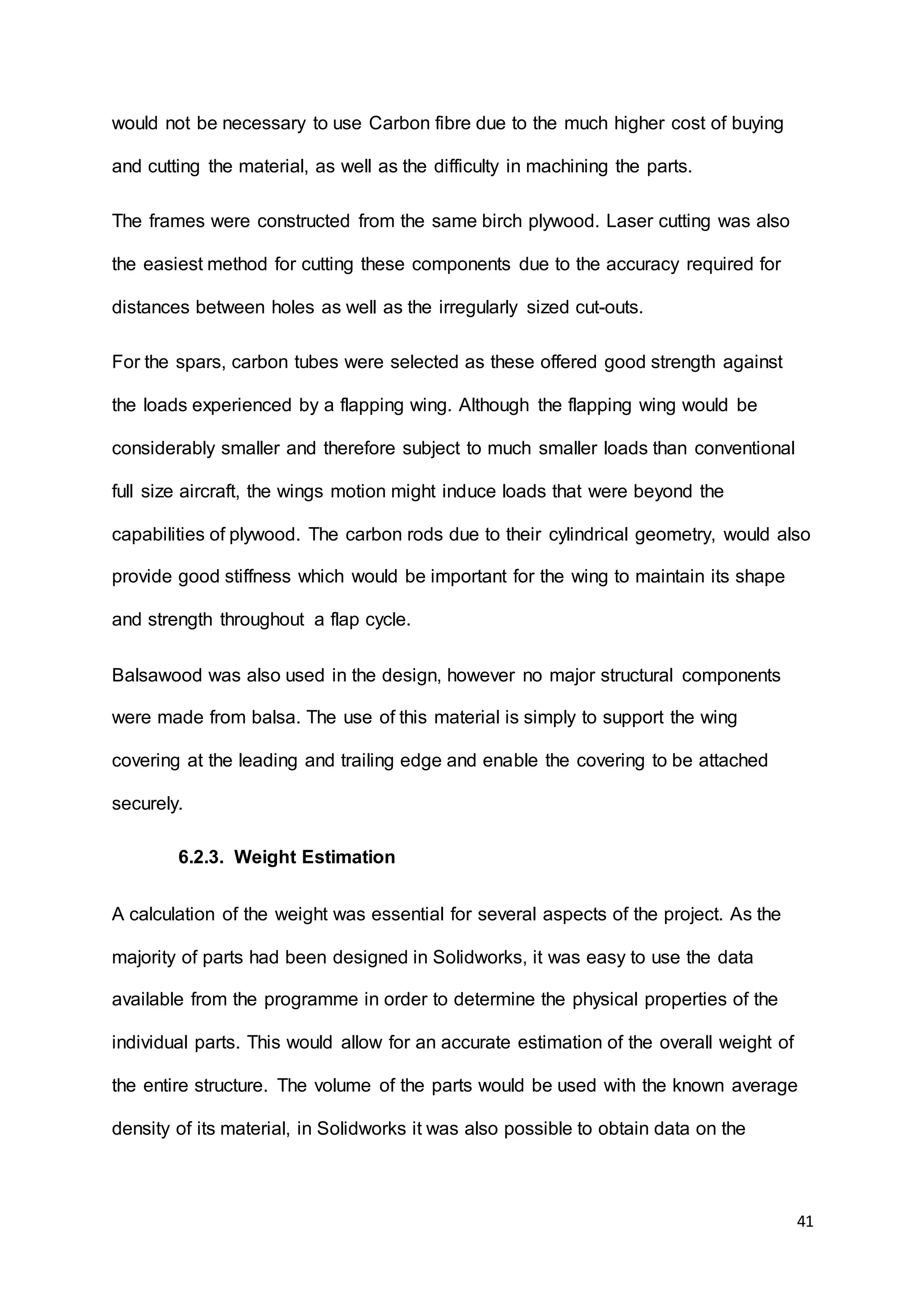

Time φ α CL

Force @1

m/s (N)

Force

@2 m/s

(N)

Force

3m/s

(N)

0 0 30 1.69 0.144918 0.57967 1.304258

0.0694 13.81 22.98 1.4623 0.125392 0.501569 1.12853

0.104 19.26 15 1.2976 0.111269 0.445077 1.001423

0.16 21.17 0 0.3493 0.029952 0.11981 0.269572

0.226 16.5 -19.28 -0.77 -0.06603 -0.26411 -0.59425

0.3125 0 -30 -0.834 -0.07152 -0.28606 -0.64364

0.43 -21.17 -10.26 -0.0014 -0.00012 -0.00048 -0.00108

0.469 -21.5 0 0.3483 0.029867 0.119467 0.268801

0.556 -13.82 23 1.4608 0.125264 0.501054 1.127372

0.59 -10.5 28.19 1.6763 0.143743 0.574971 1.293685

Figure 45: The tableof numericalvaluesshowing thepredicted forces forfigure10. Valuesof 1.3N at

peaklifting forcewould be good to obtain experimentally and show thatthedesign of thetest rig could

be feasible.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-65-2048.jpg)

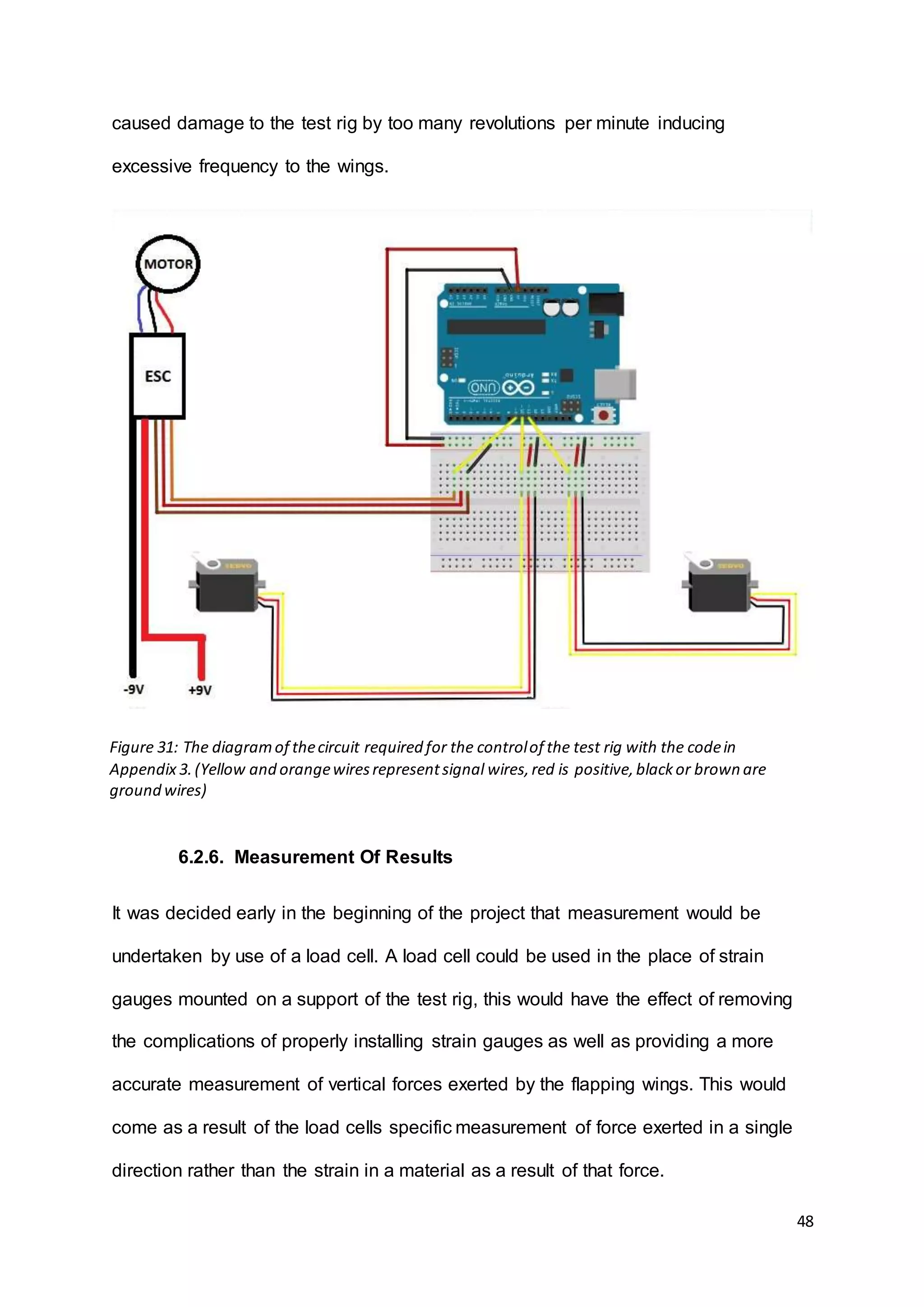

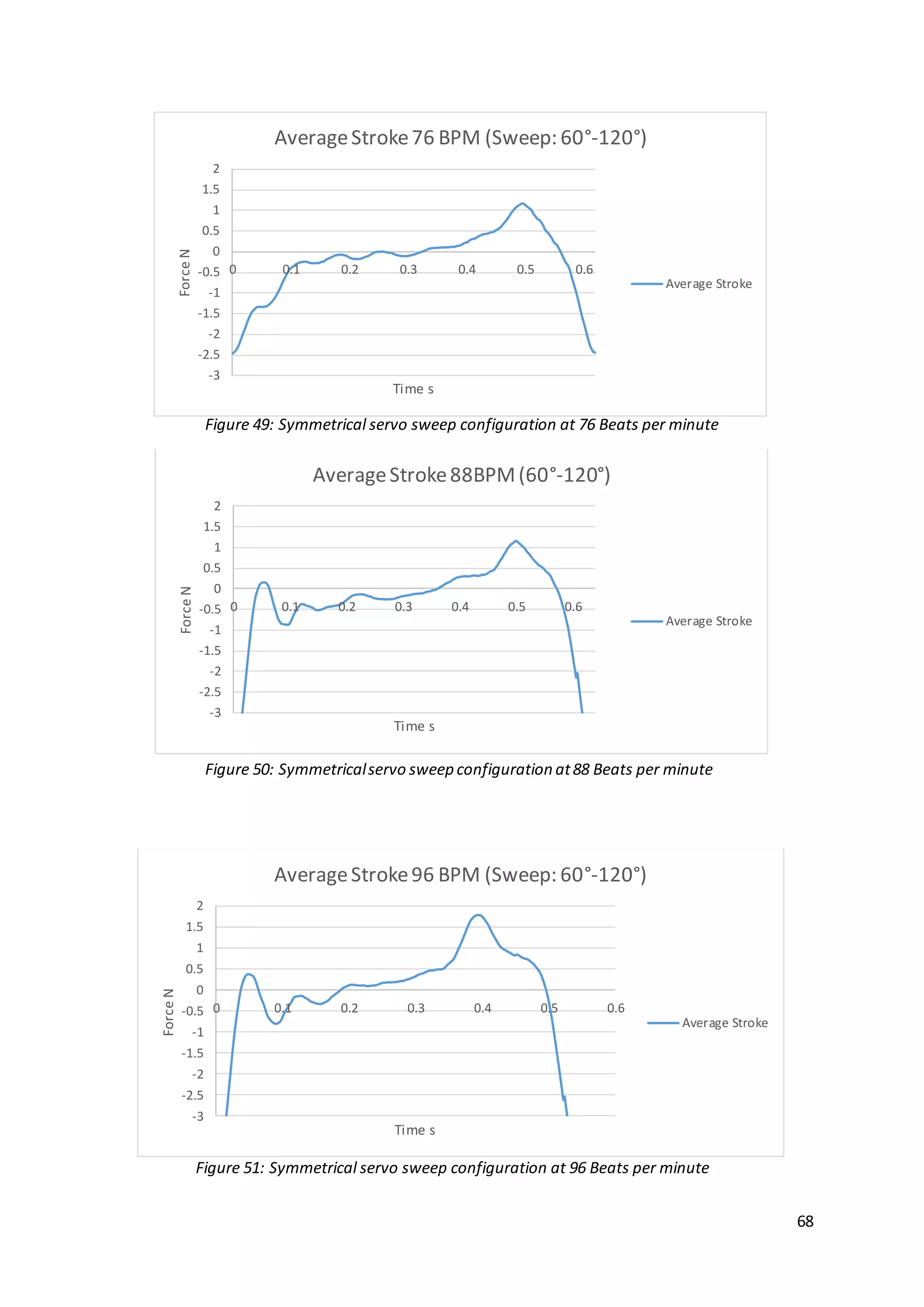

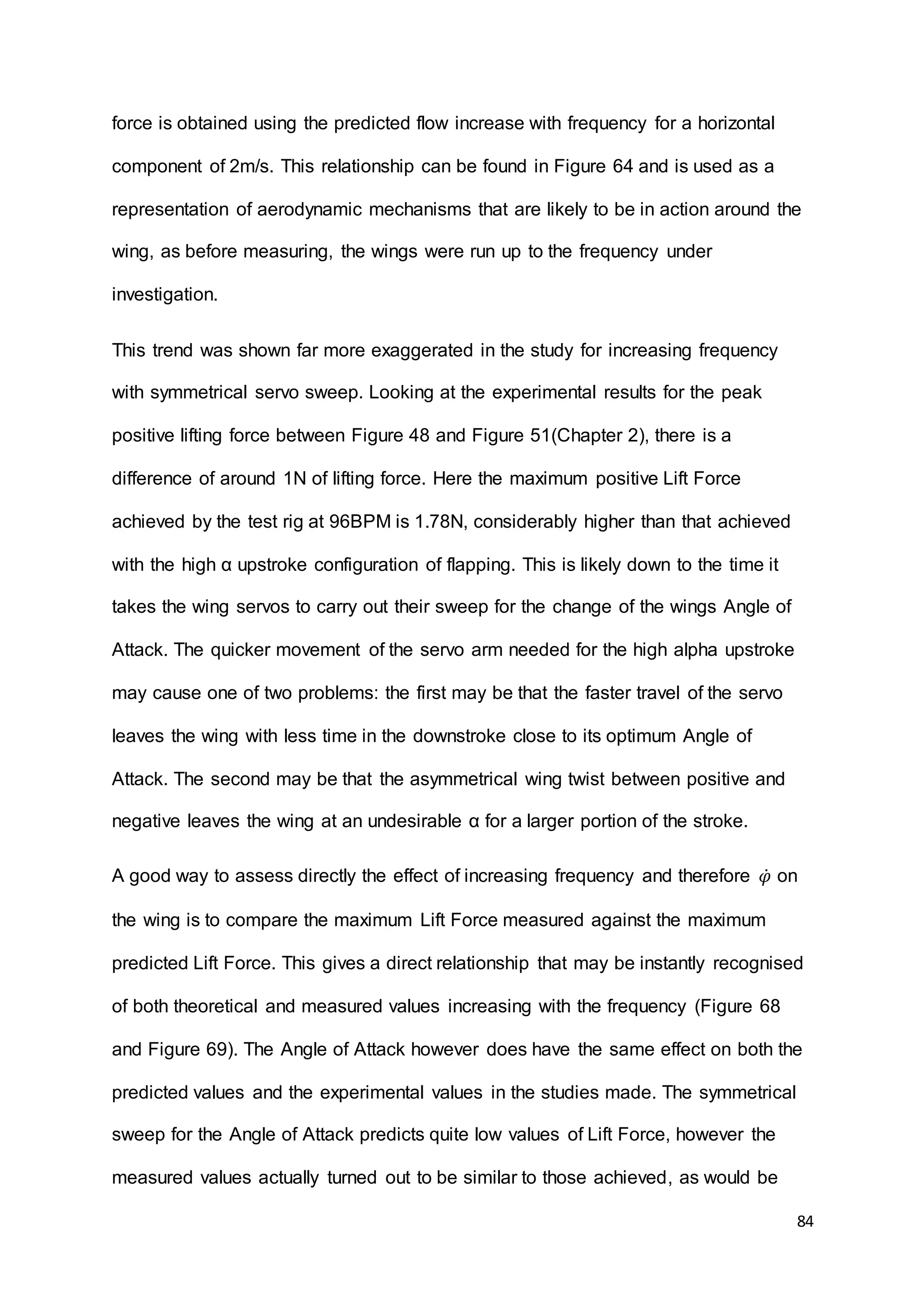

![69

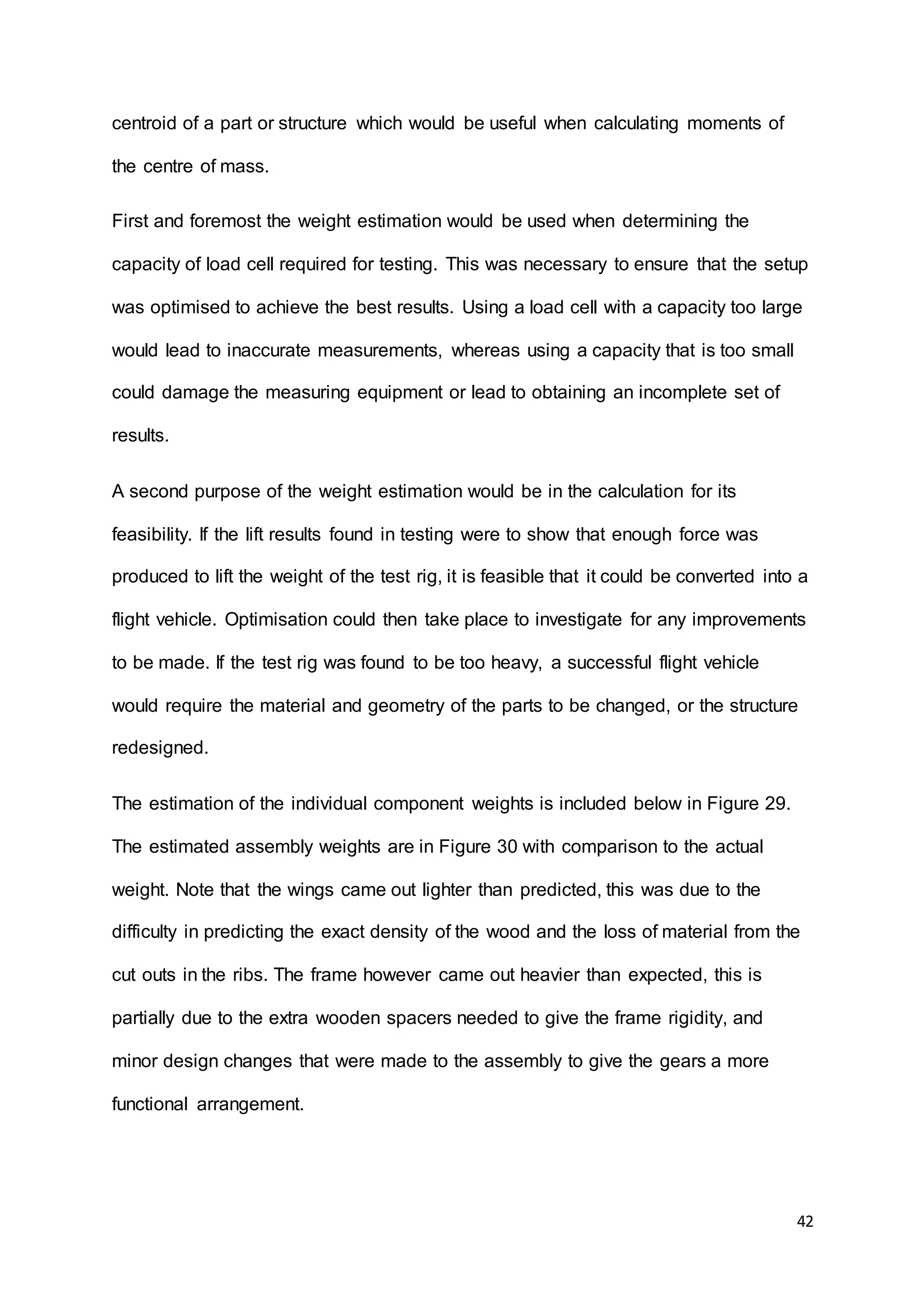

7.2.2. High Positive α Study With Increasing Frequency

The next study made was again into the increasing frequency of flapping, but with

the variation of a much higher Angle of Attack on the upstroke. As mentioned by

Anderson (2001), the rapid pitch up at the end of the stroke allows higher CL to be

achieved towards the end of the lift stroke [20]. The higher α in the upstroke should

also produce less negative force due to the reduced surface area perpendicular to

the velocity of the wings centre of mass. The results for this study are plotted in

Figures 52, 53, 54 and 55. All increments in the increase in frequency have been

kept the same as for the symmetrical servo sweep study.

-2

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8

ForceN

Time s

AverageStroke64 BPM (Sweep:60°-160°)

Average Stroke

-2

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6

ForceN

Time s

AverageStroke76 BPM (Sweep:60°-160°)

Average Stroke

Figure 52: The Force plot for the high positive α study at 64 beats per minute

Figure 53: The Force plot for the high positive α study at 76 beats per minute](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-69-2048.jpg)

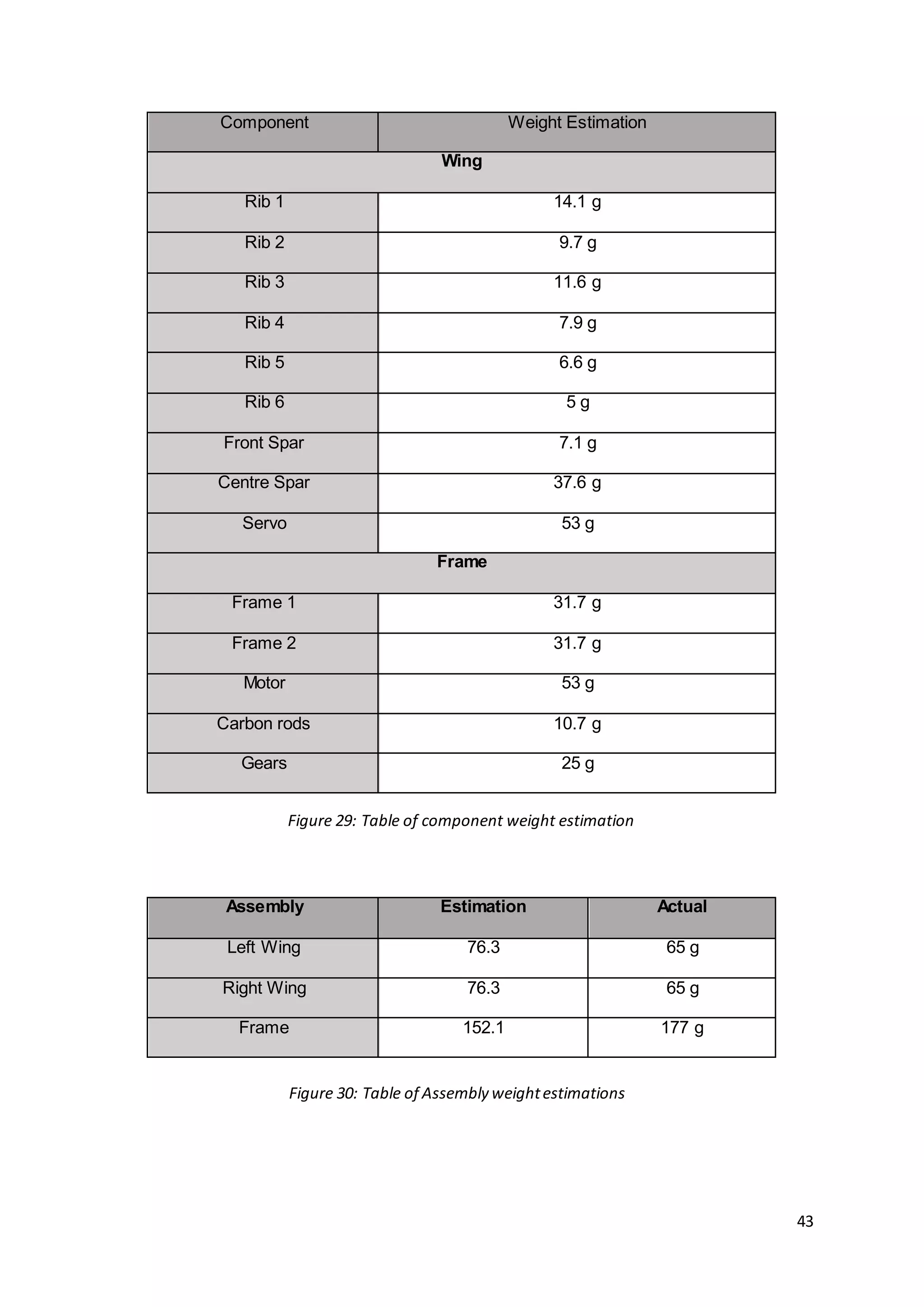

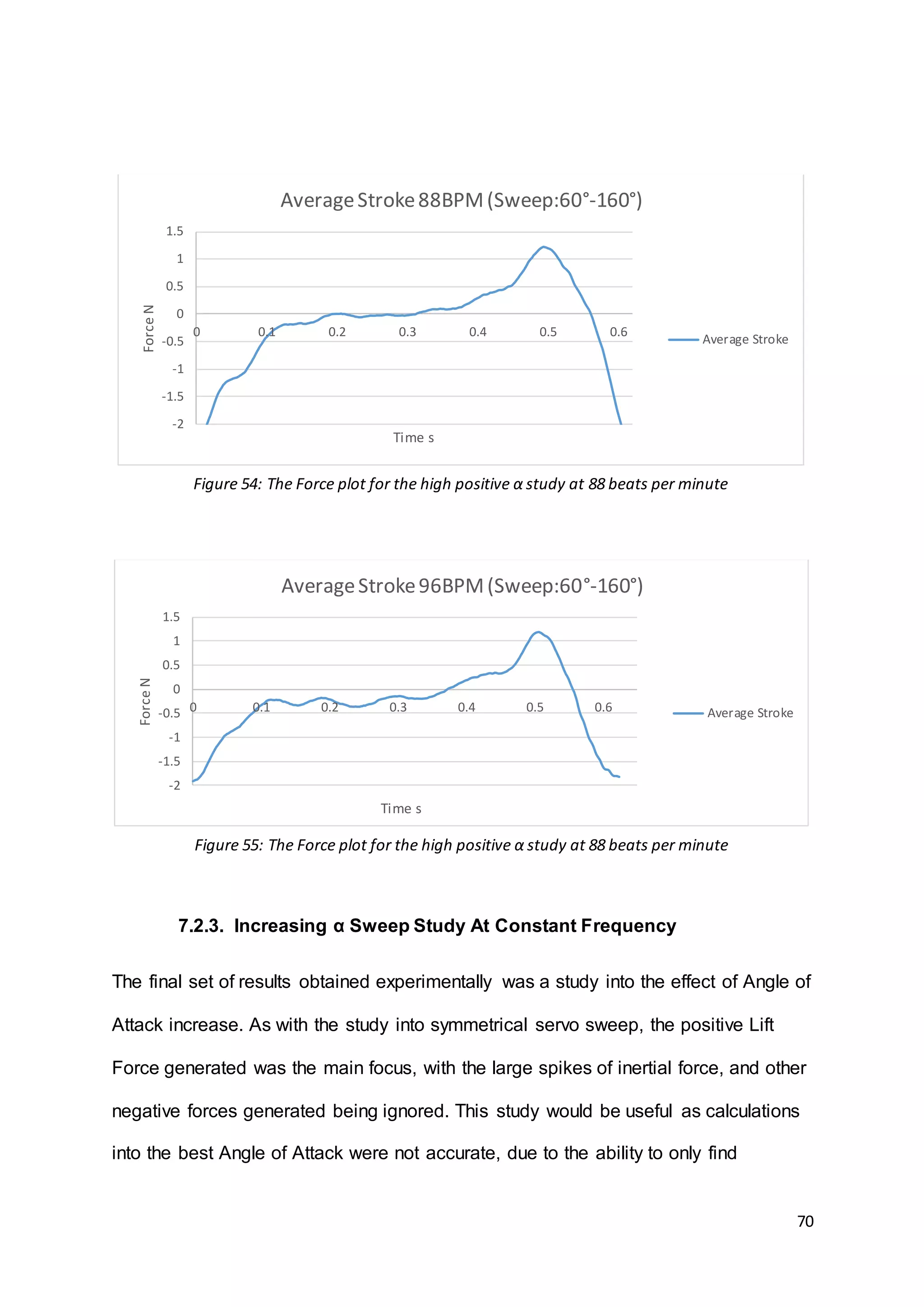

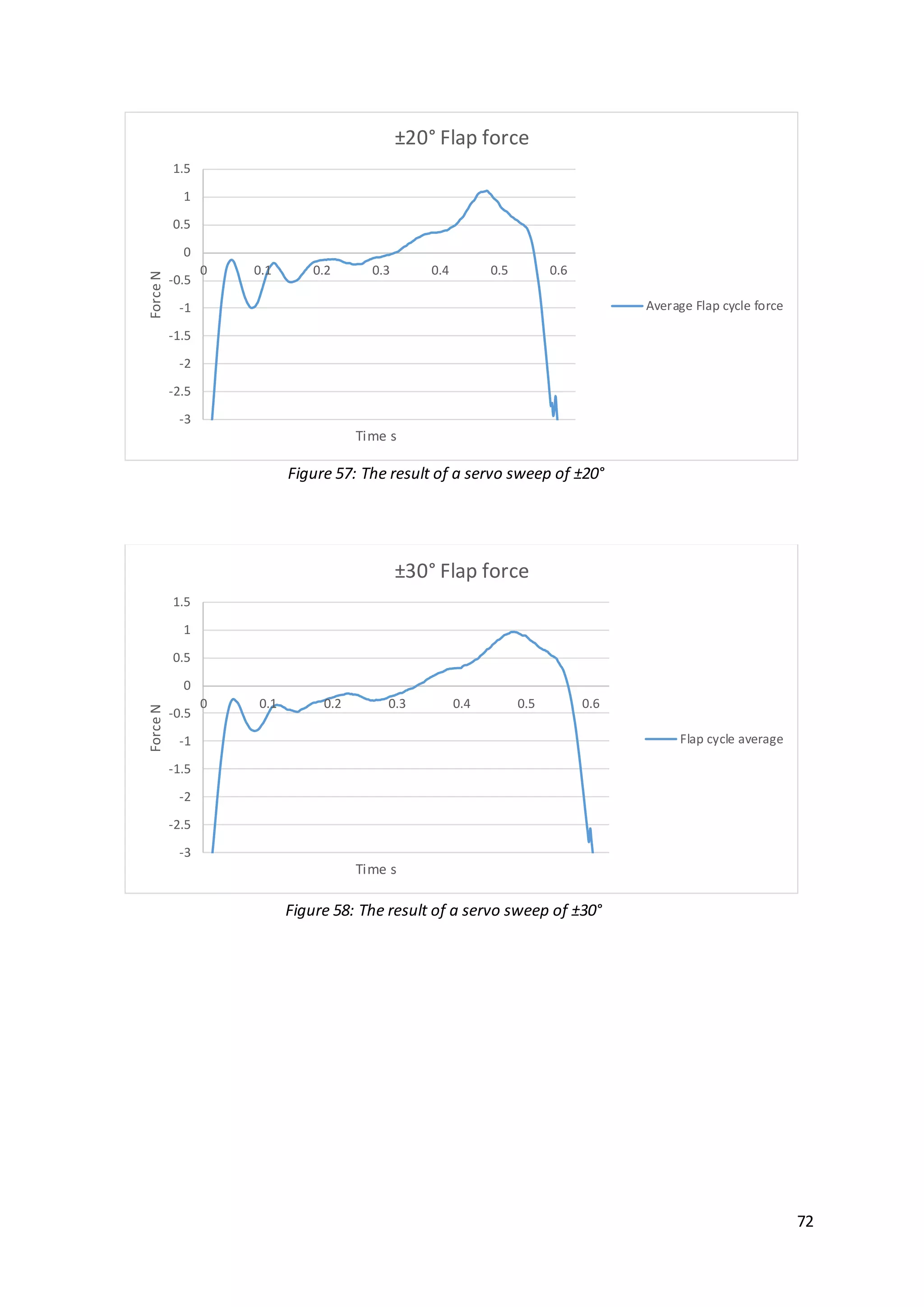

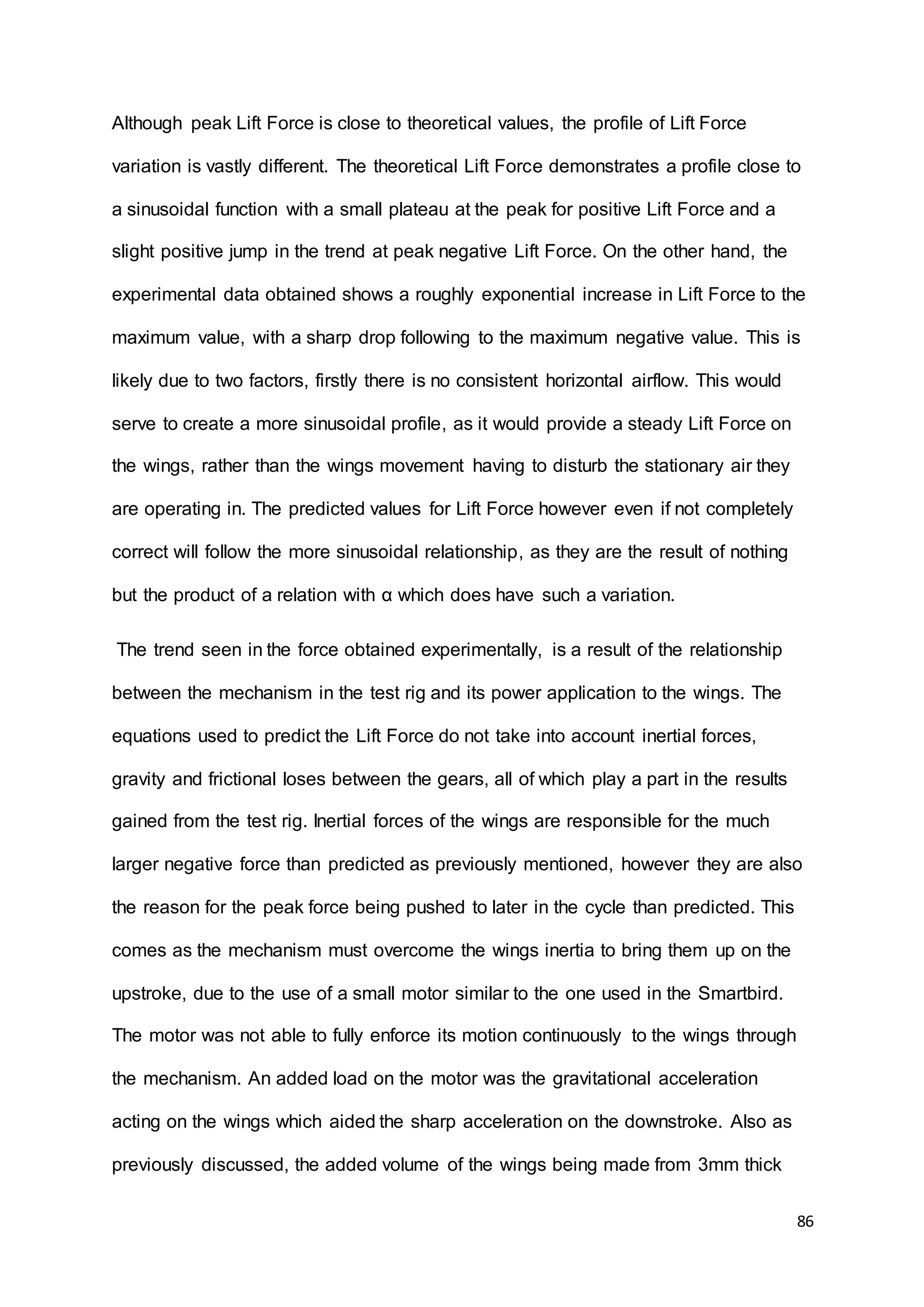

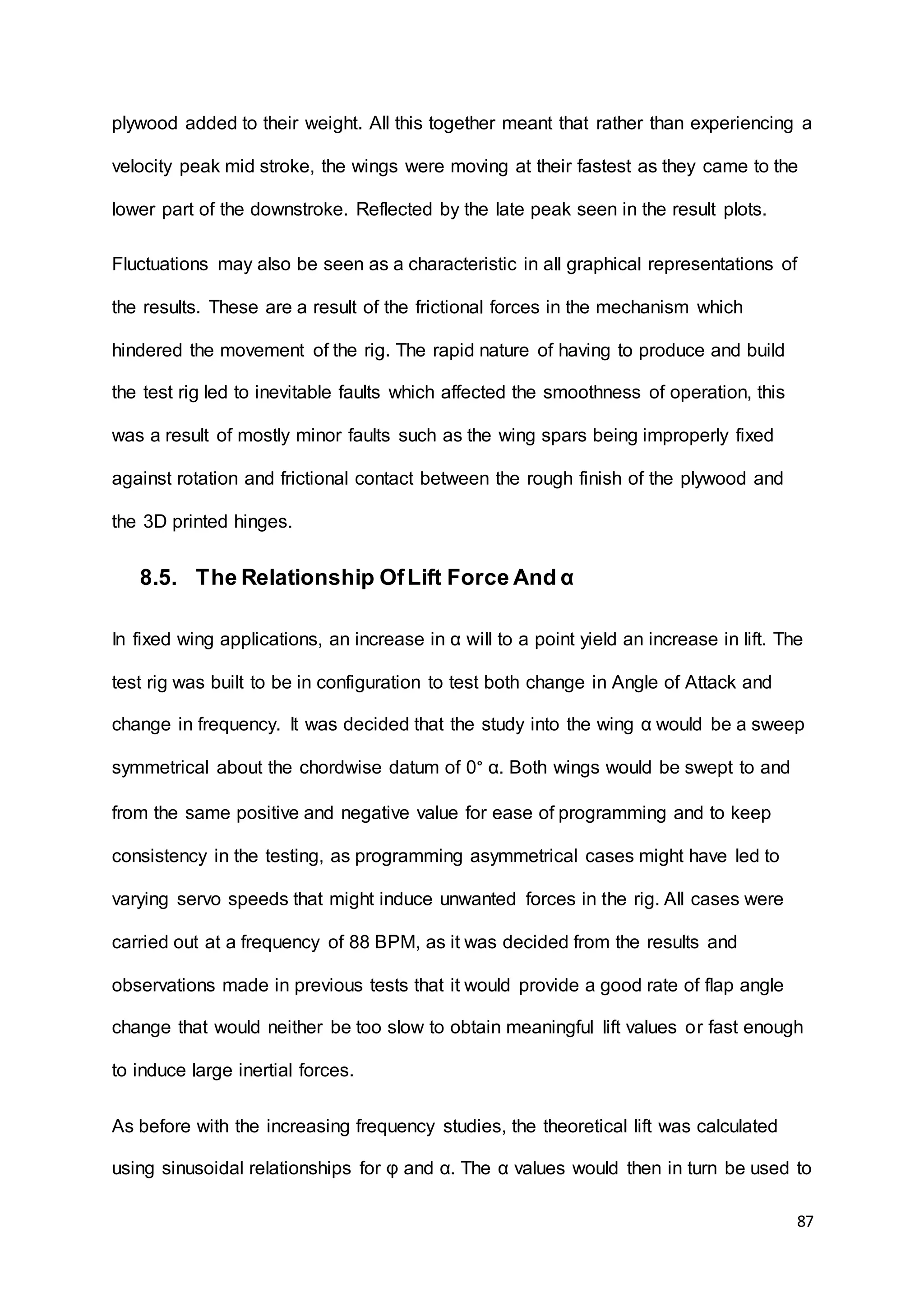

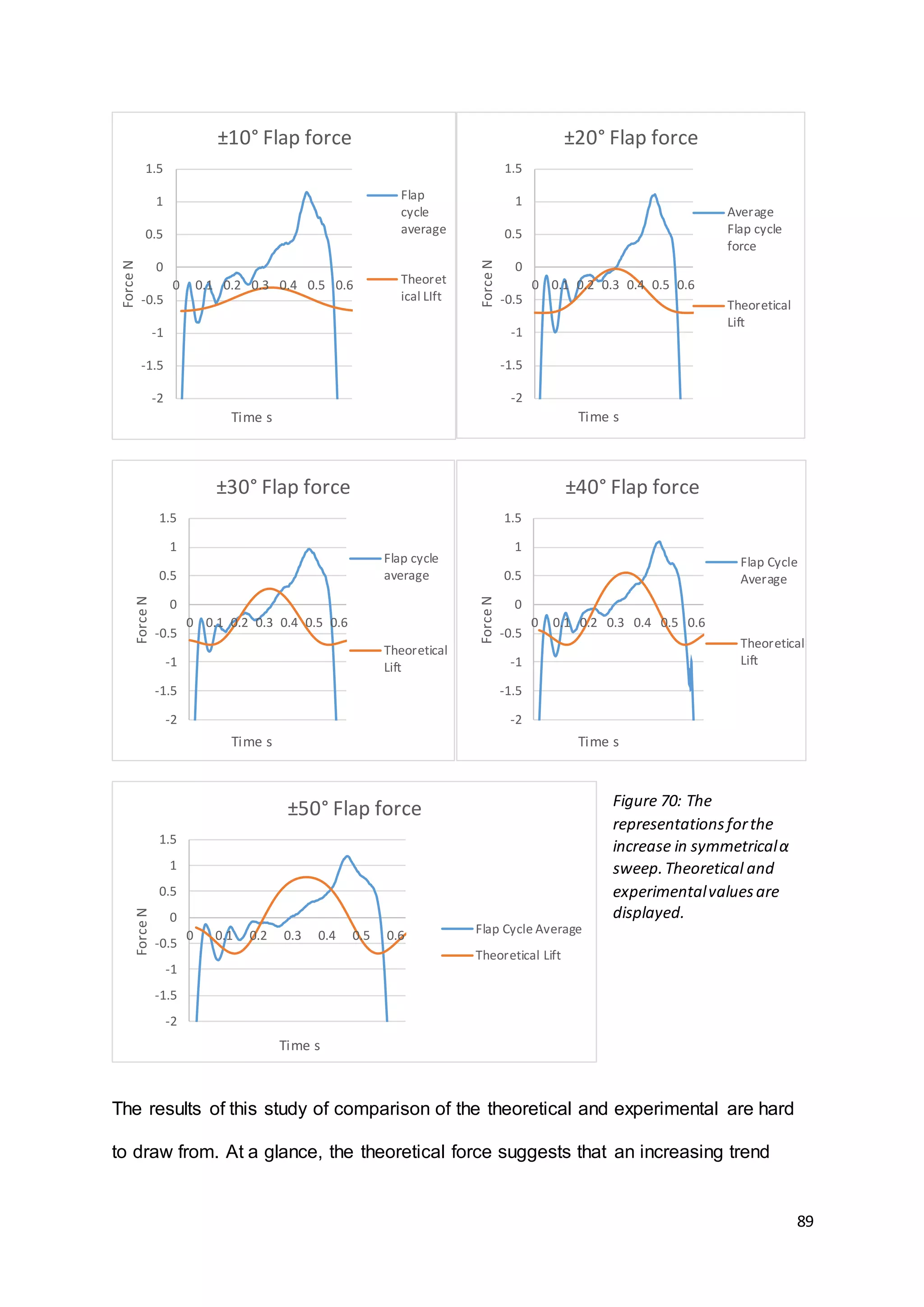

![71

solutions to a static wing in two dimensional flow. The case of flapping would present

a far more difficult problem and for the purposes of this project would be better

analysed experimentally. The symmetrical servo sweep analysed, ranged from ±10°

through to ±50° in increments of 10°. These results are shown in Figure 56 to 60.

The same procedure was used as for the previous results by applying Sane and

Dickinson’s method [2] of averaging all strokes measured into a single wing beat.

This would keep all results obtained consistent.

-3

-2.5

-2

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6

ForceN

Time s

±10° Flap force

Flap cycle average

Figure 56: The result of a servo sweep of ±10°](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-71-2048.jpg)

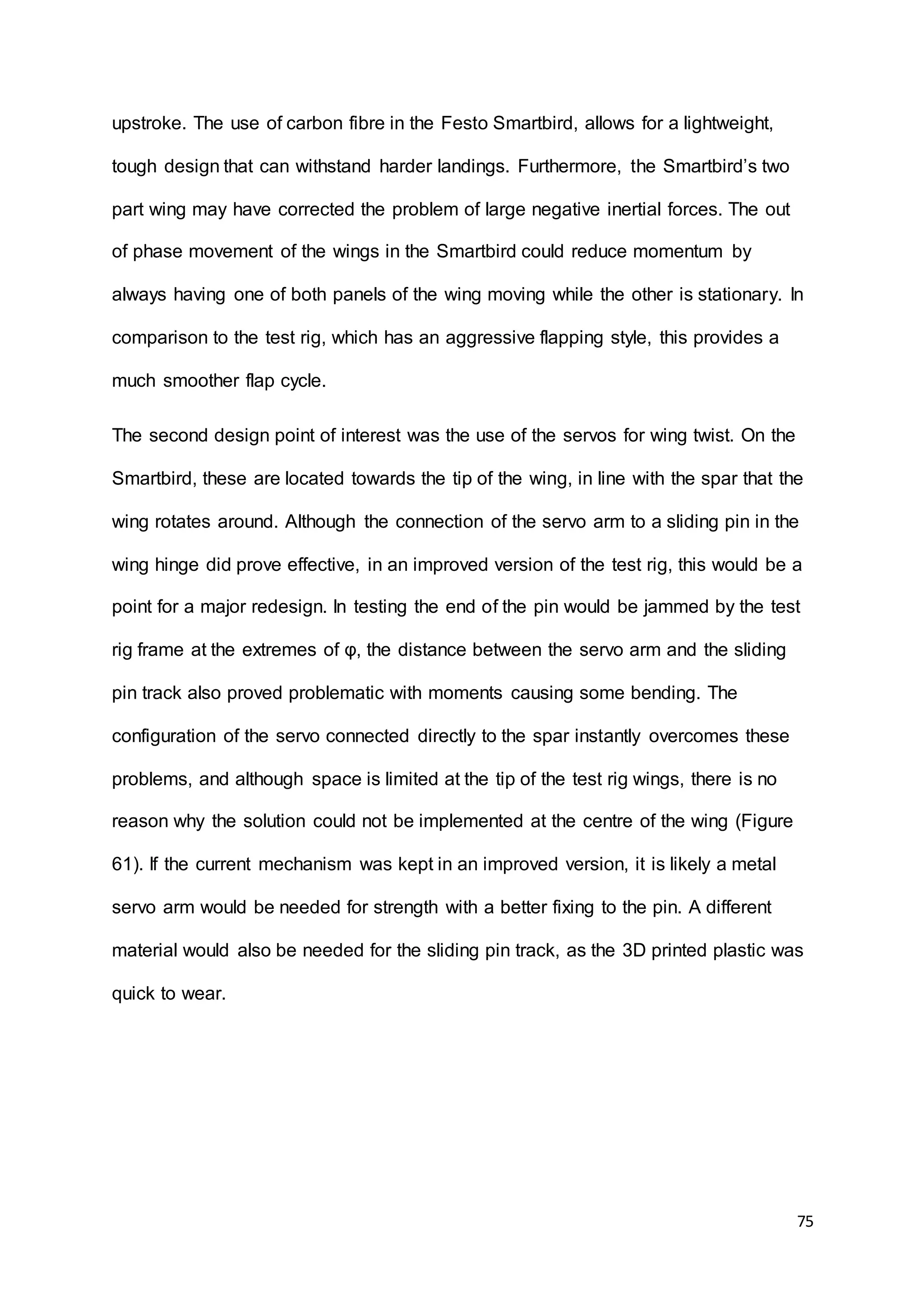

![74

8. Chapter 3: Analysis

The results for the numerical modelling and the experimental studies allowed a

comparison between the theoretical calculations and reality. Not only would these

comparisons provide answers, but the differences between the experimental results

and the theory proved to be just as revealing as the similarities as to the challenges

of flapping wing flight. As well as considerations that would need to be made or

addressed in the design of an MAV. These answers or new challenges would not

only come from the results but also from the design and operation of the test rig,

revealing design faults that may have already been addressed by the designers of

previous successful projects such as the Festo Smartbird[3].

8.1. The Design

The selection of wood as the predominant material was chosen because of the

speed in producing parts by laser cutting. However this added unnecessary weight to

the test rig. The 3mm and 5mm thick plywood used is the same as that used in

remote control model aeroplanes. However these thicknesses were more than

required as the structure proved plenty strong enough. As to the loads induced on

the wood, the design played well to the material strengths, adding to the case for the

potential of thinner wood. Alternatively, the ribs could have been made from much

lighter balsa wood due to the loads being quite low and the structure more than

adequate.

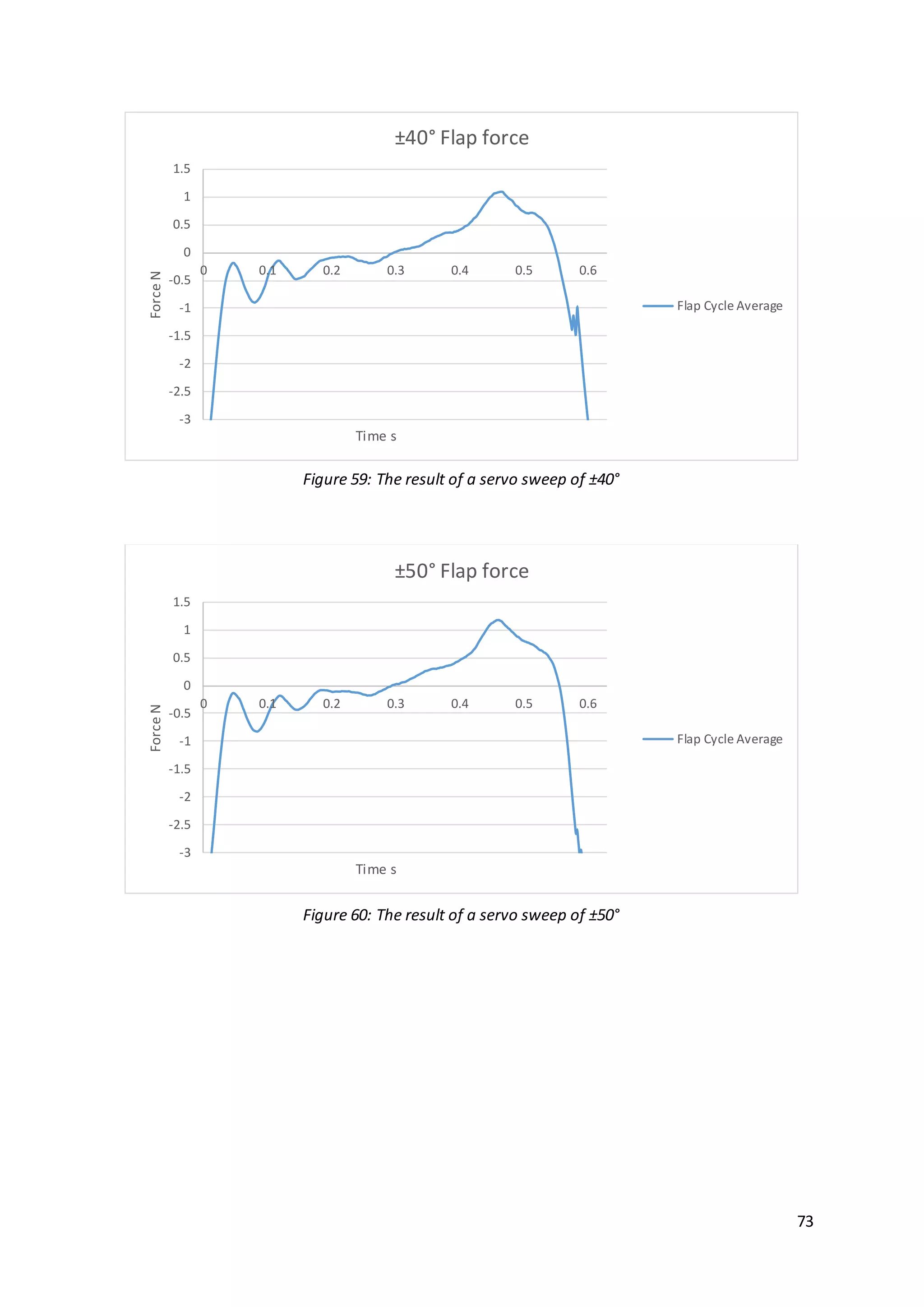

Looking at the results of experimental testing, the most noticeable characteristic is

the large peak of negative force. This is created by the large inertial forces produced

by the wings, as their momentum is rapidly damped at the end of each downstroke.

This is amplified by the motion of the mechanism quickly lifting the wings for the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-74-2048.jpg)

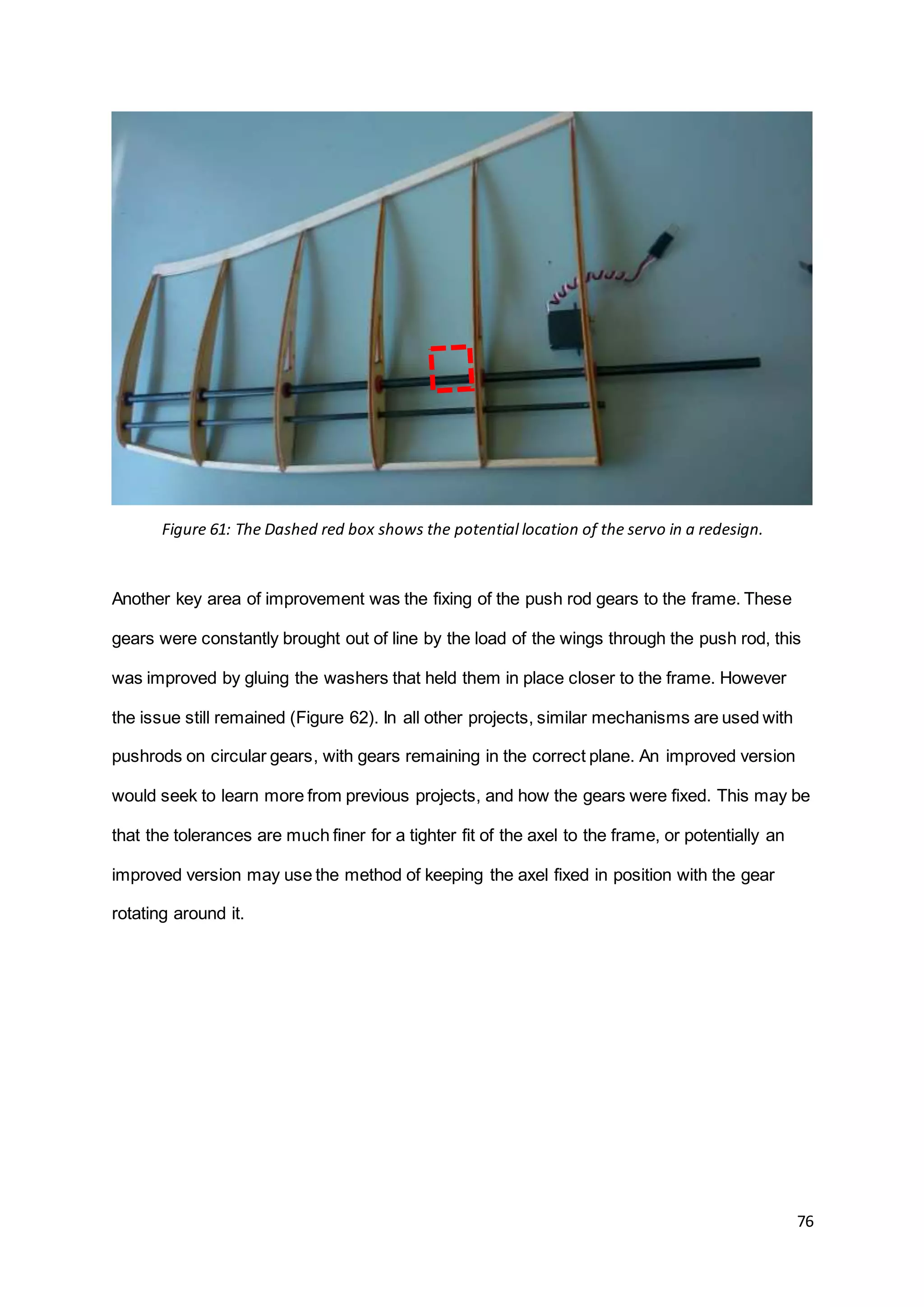

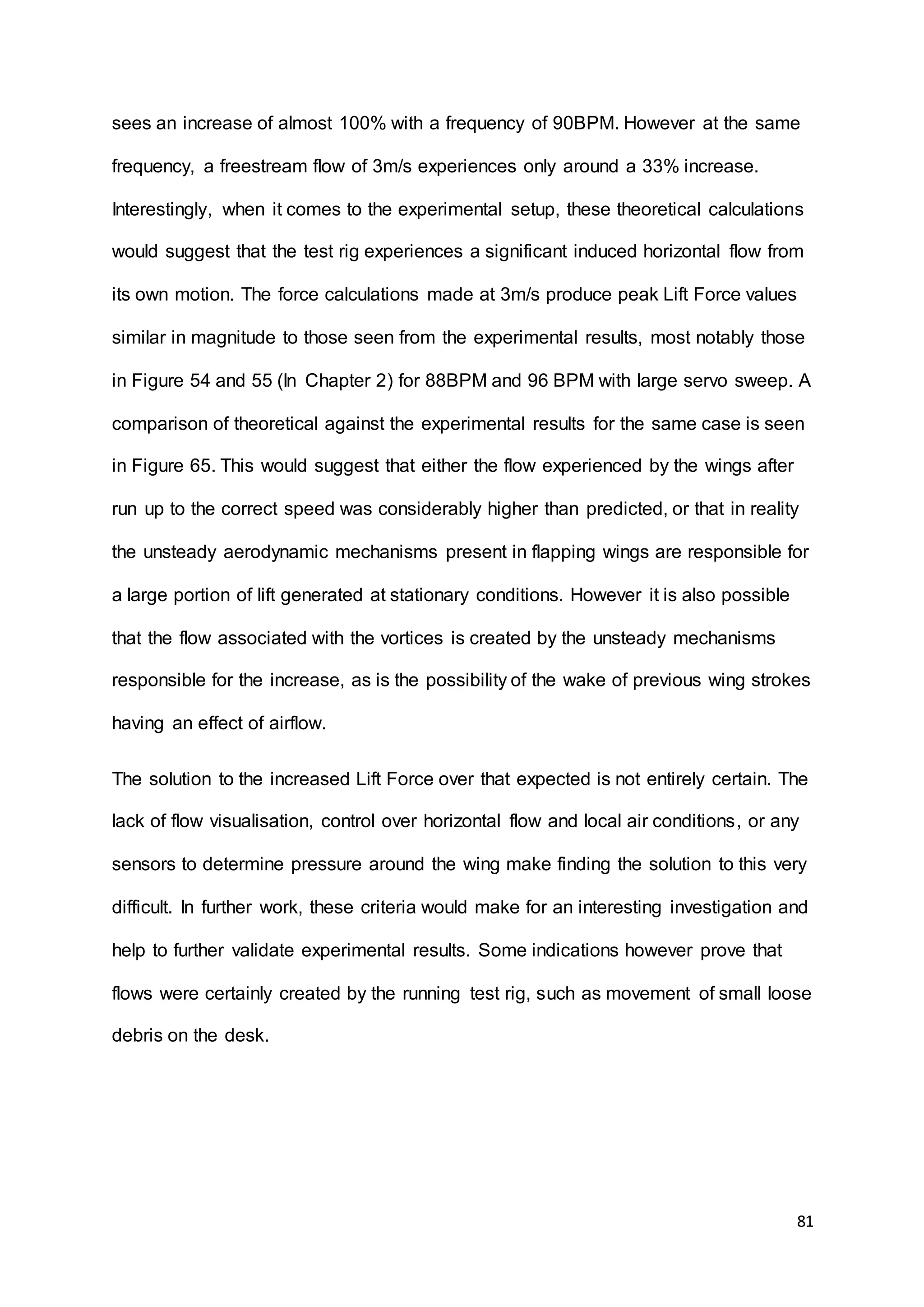

![78

With further work on the project, the addition of sensors would be the most practical

and useful modification. A sensor could easily be positioned on the frame to register

the movement of one of the gears or the wing spar. This could be used as a trigger

to activate a twist of the servo with regard to its current position. This addition would

alleviate the need for calibration and the correct starting position of the test rig,

allowing the parameters affecting beats per minute to be changed exclusively with

the speed of the motor.

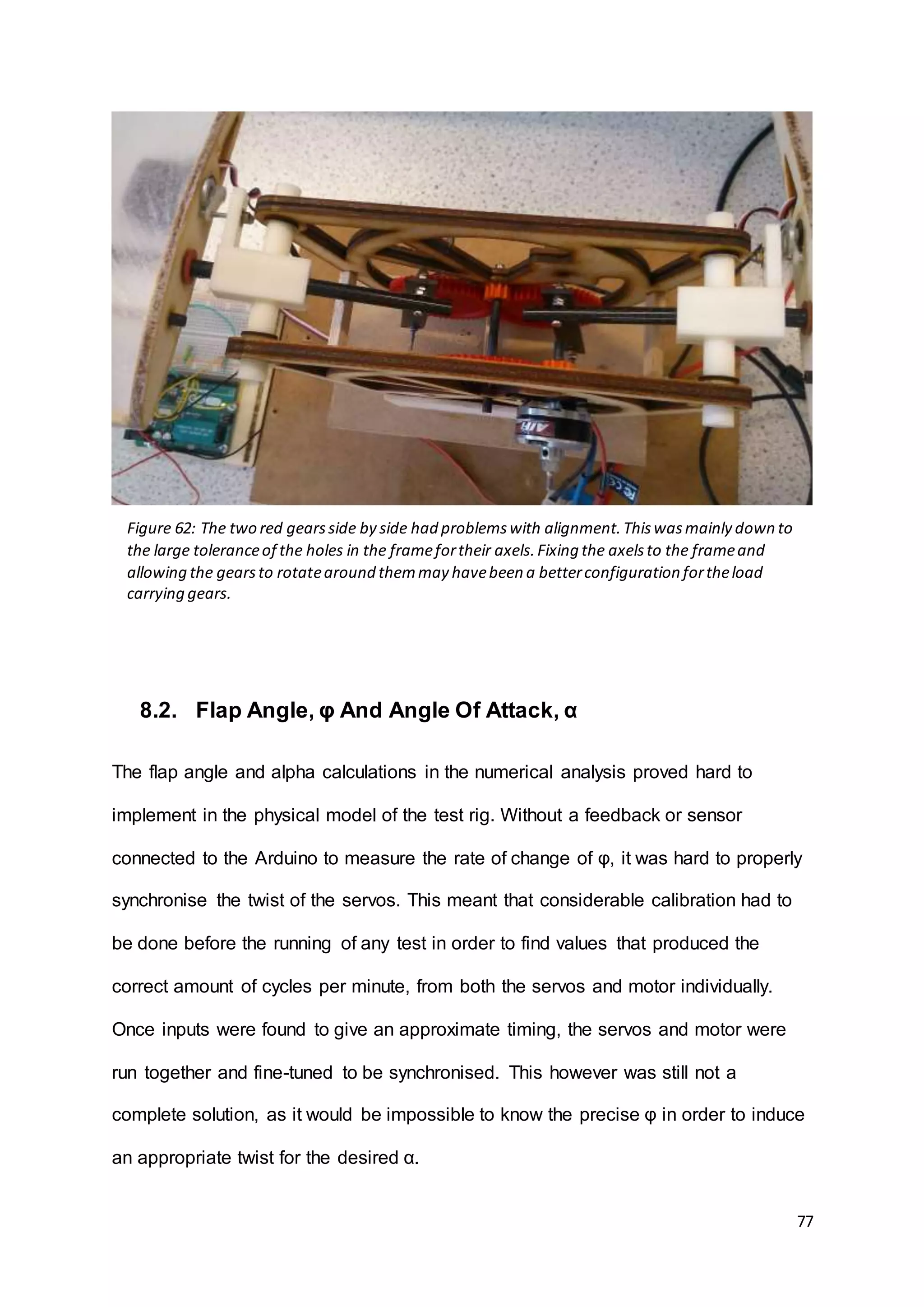

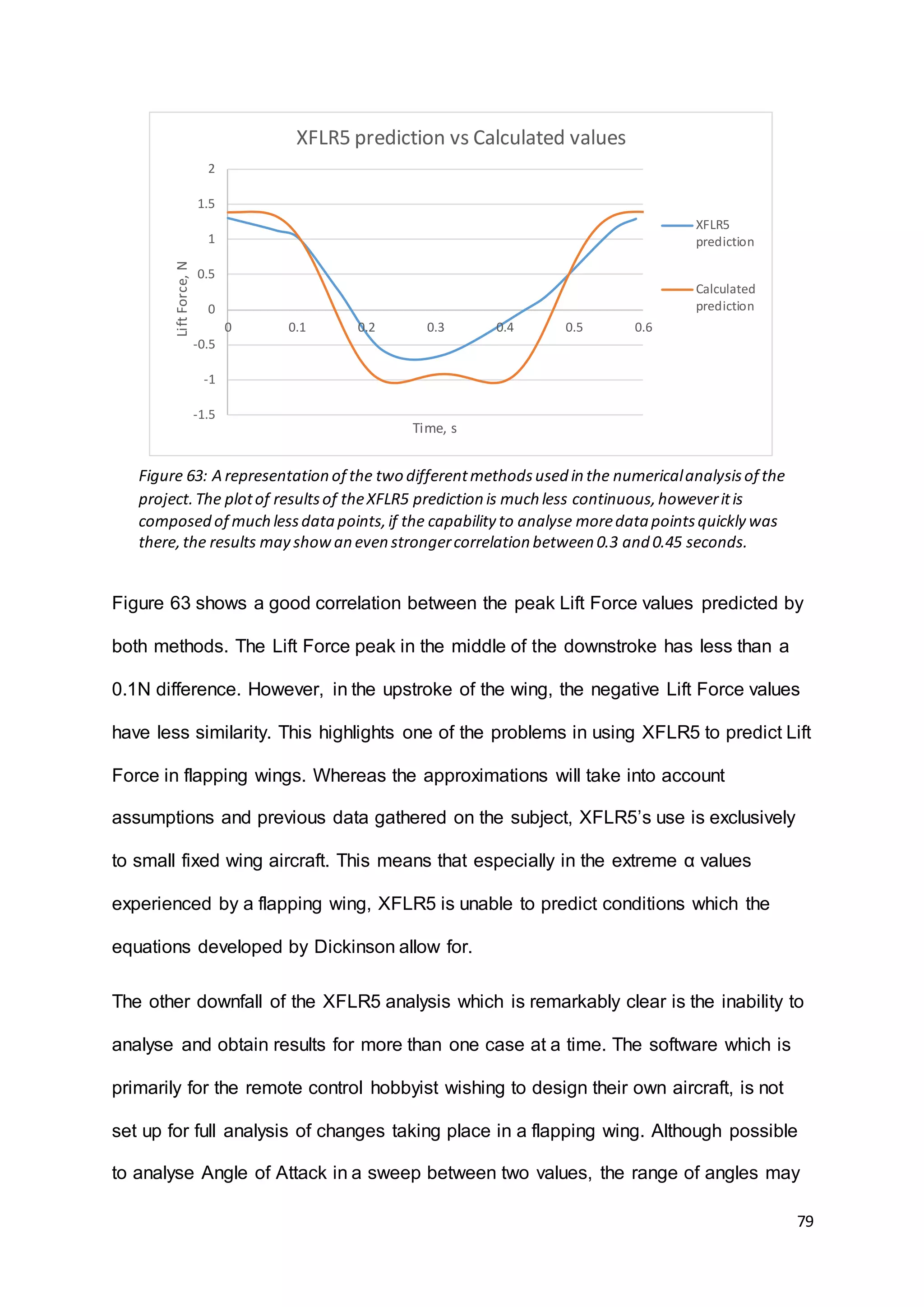

8.3. Comparisons Between The Lift Force Calculated And Lift

Force Determined Experimentally.

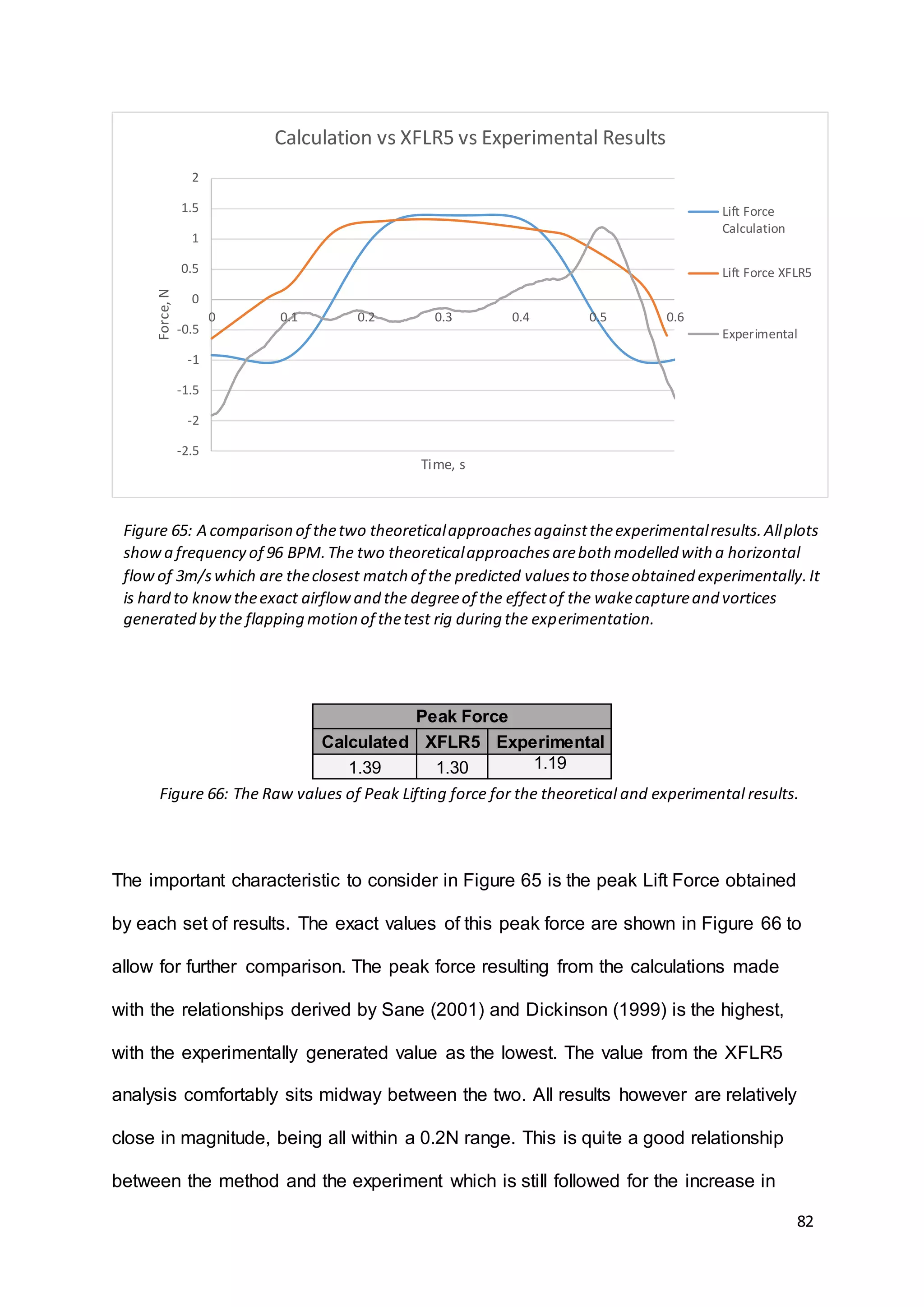

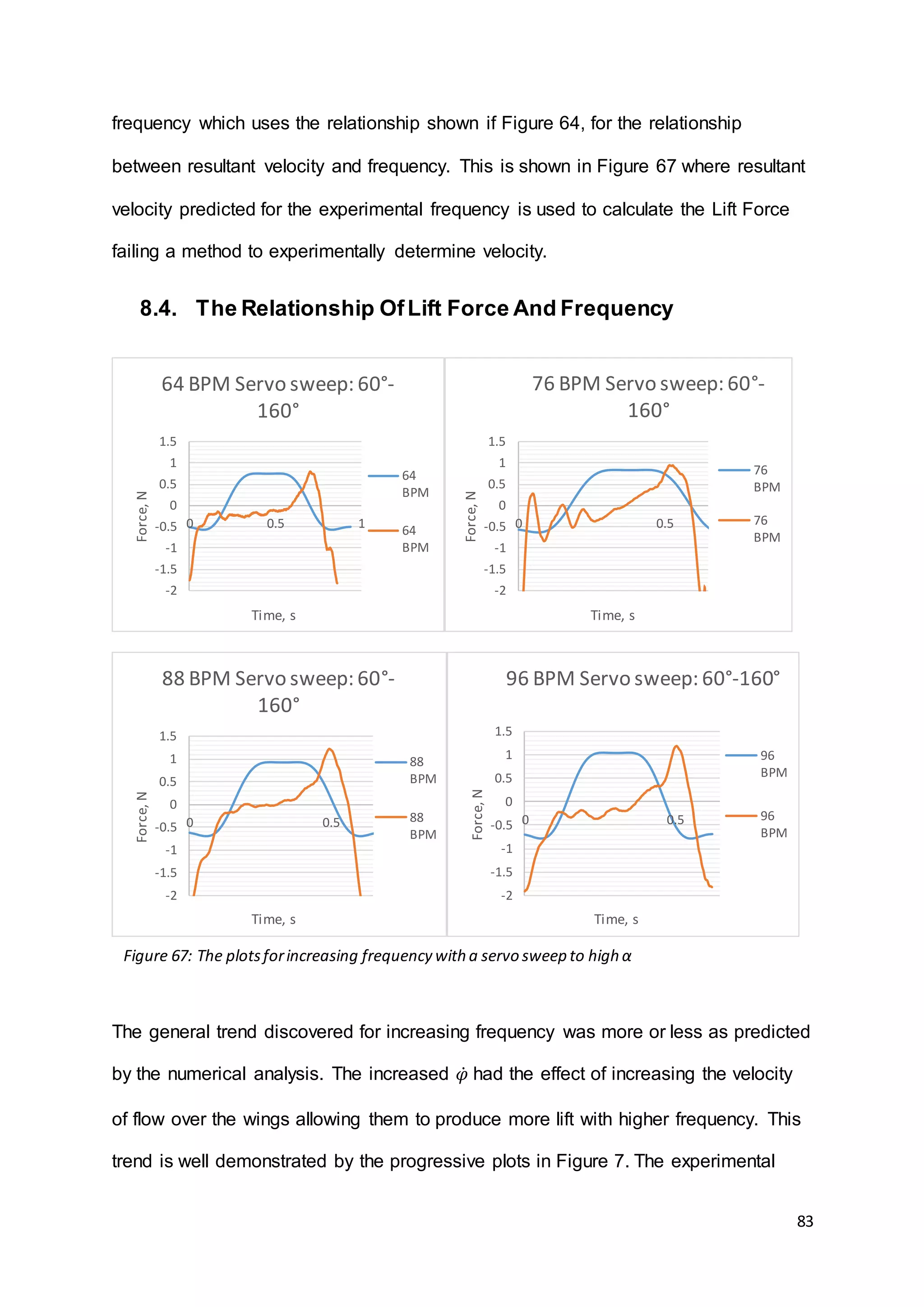

Due to the nature of the numerical analysis, it was possible to use two different

methods for calculating the Lift Force produced by the wings. One method would

apply the calculation of sinusoidal functions of φ and α as by Whitney and Wood

(2012) [22], to then apply equations for the approximation of CL and CD as by

Dickinson et al (1999) [23] to finally produce a force prediction from the lift equation.

The second method for theoretically determining the lift would again use calculation

of φ and α to then run an analysis on increments of the flap cycle in XFLR5 to find a

CL, this would then as before, be used in the lift equation. Both methods would have

their advantages and disadvantages but when comparing the two methods over a

single case with identical values of φ, α, 𝑉∞ and ρ, there is a strong correlation

between the results obtained. A comparison is shown in Figure 63 with a comparison

between the methods for a case of 96BPM, an Angle of Attack sweep of -30° to

+70°, and a freestream velocity of 3m/s.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-78-2048.jpg)

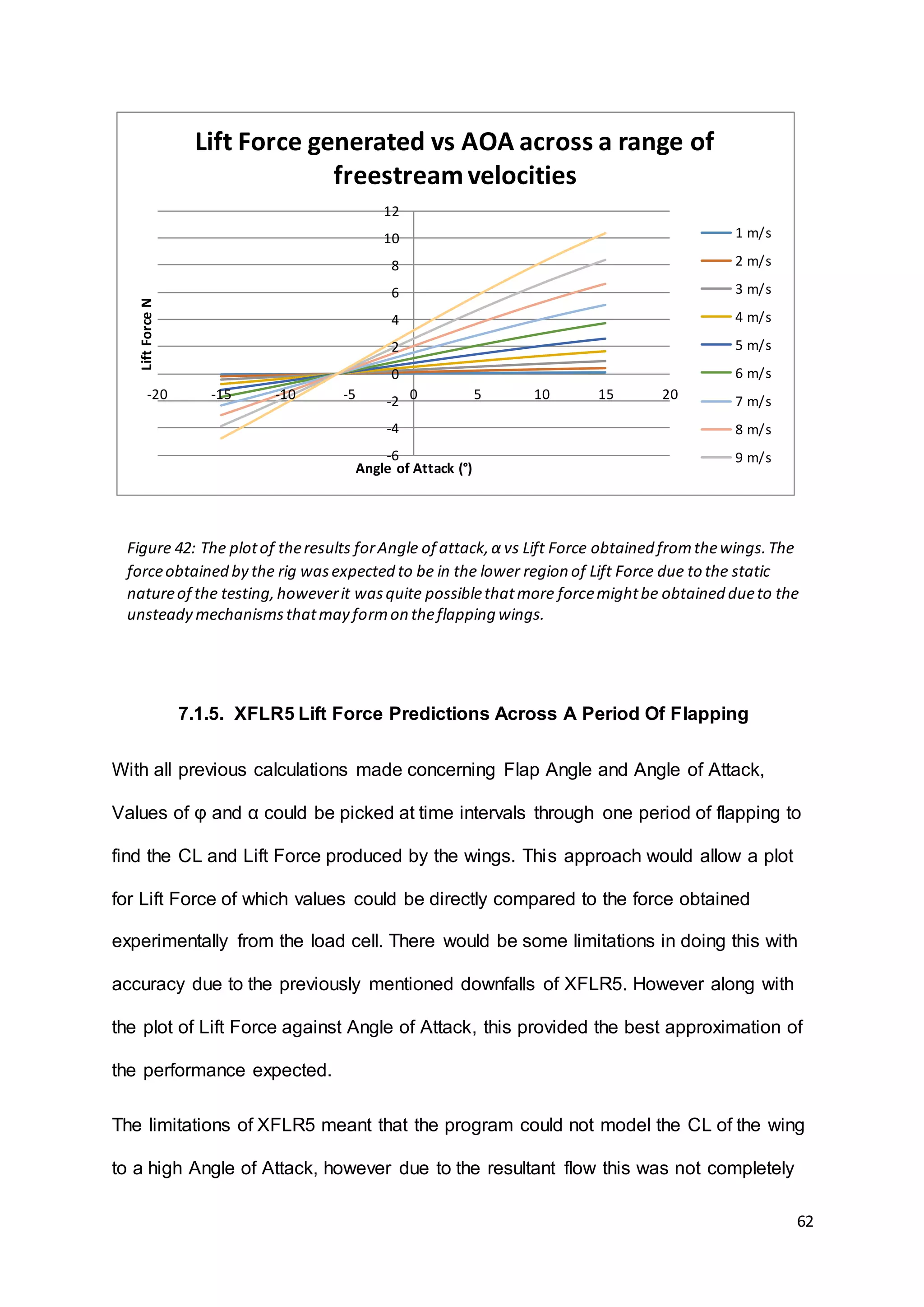

![80

only span across a maximum of 40° at a time. The software is also able to do the

same with freestream velocity. However in the example of a flapping wing vehicle,

the software cannot sweep through more than one set of parameters at a time, and

in the case of wing dihedral which is constantly changing in flapping flight, this must

be altered manually every time. To this end, the plot of the XFLR5 results is

composed of only 10 data points, with plots for the calculated values containing

some 37 data points. This becomes obvious when viewing them side by side, as the

plot for the XFLR5 values is far less continuous in profile due to a far less regular

spacing of values. This is not to say however, that an XFLR5 analysis with more data

points could provide a much more coherent analysis.

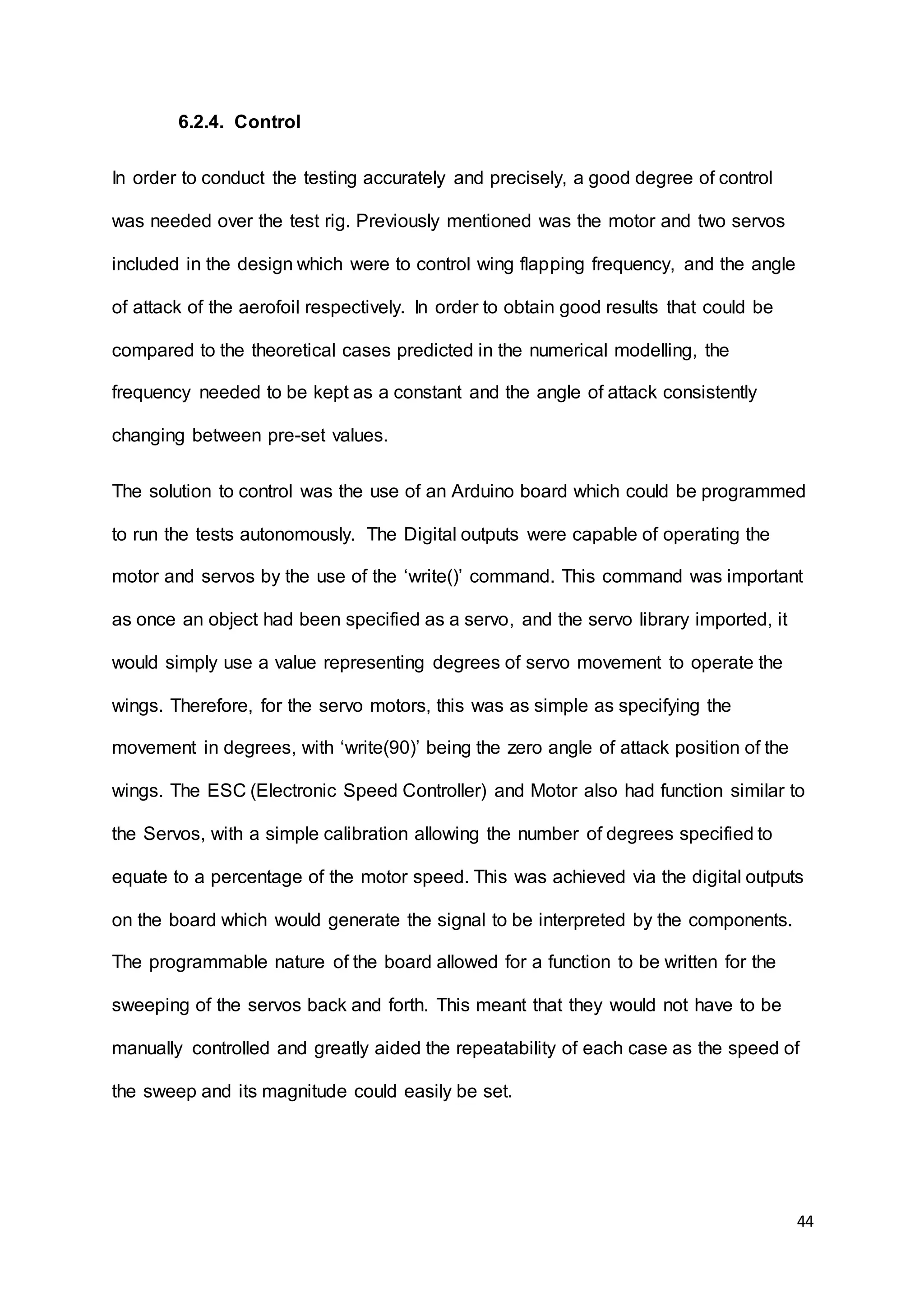

Figure 64 shows the predicted increase in the freestream flow over its value due to

the added component of the wings velocity in the downstroke. From the results of the

application of blade element theory, which treats the wing as a propeller blade

moving at a constant velocity perpendicular to an oncoming flow, it can be seen that

the increase becomes less with increasing horizontal airspeed. An airspeed of 1m/s

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

0 20 40 60 80 100

Velocity,m/s

Frequency BPM

Low Speed resultantvelocity induced by flapping

@ 1 m/s

@ 2 m/s

@ 3 m/s

Figure 64: The predictions for low velocity resultant flow over the wings using Blade element

theory [27].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-80-2048.jpg)

![88

find CL and then Lift Force which could be plotted alongside that obtained

experimentally for comparison. The Lift Force obtained from the load cell was

averaged over six wing beats in order to give an average set of values for a single

flap cycle. This approach to the theoretical calculations from the work of both

Whitney, J.P. (2012) [22] and Dickinson, M.H. (1999) [23] proved the most

straightforward way of processing the large amount of data generated in testing. This

coupled with the method of presenting experimental results by Sane, S.P. (2001) [2]

provided the best way of presenting both the predicted and actual values for a

specific combination of the frequency and amplitude of α applied to the test rig

wings.

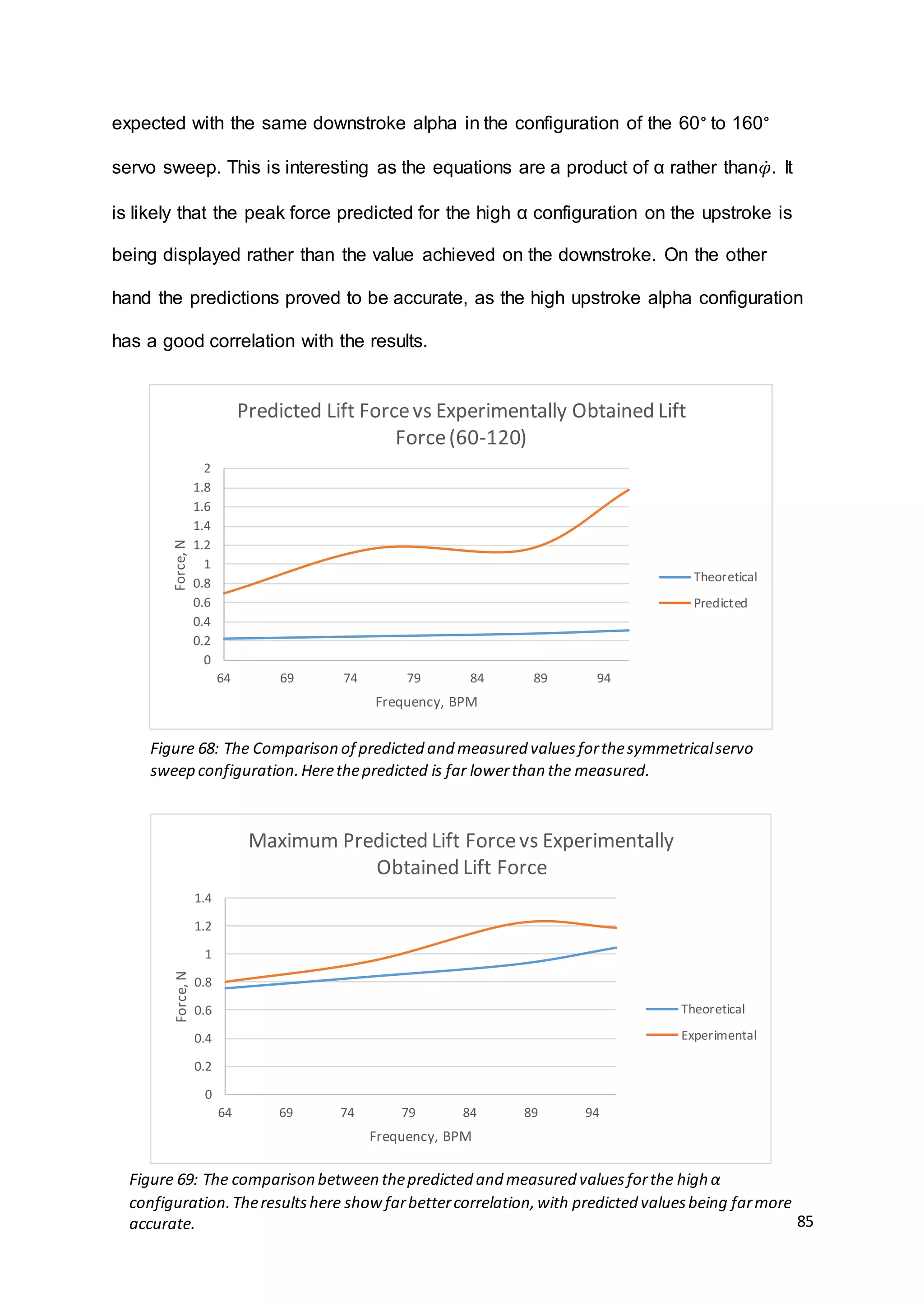

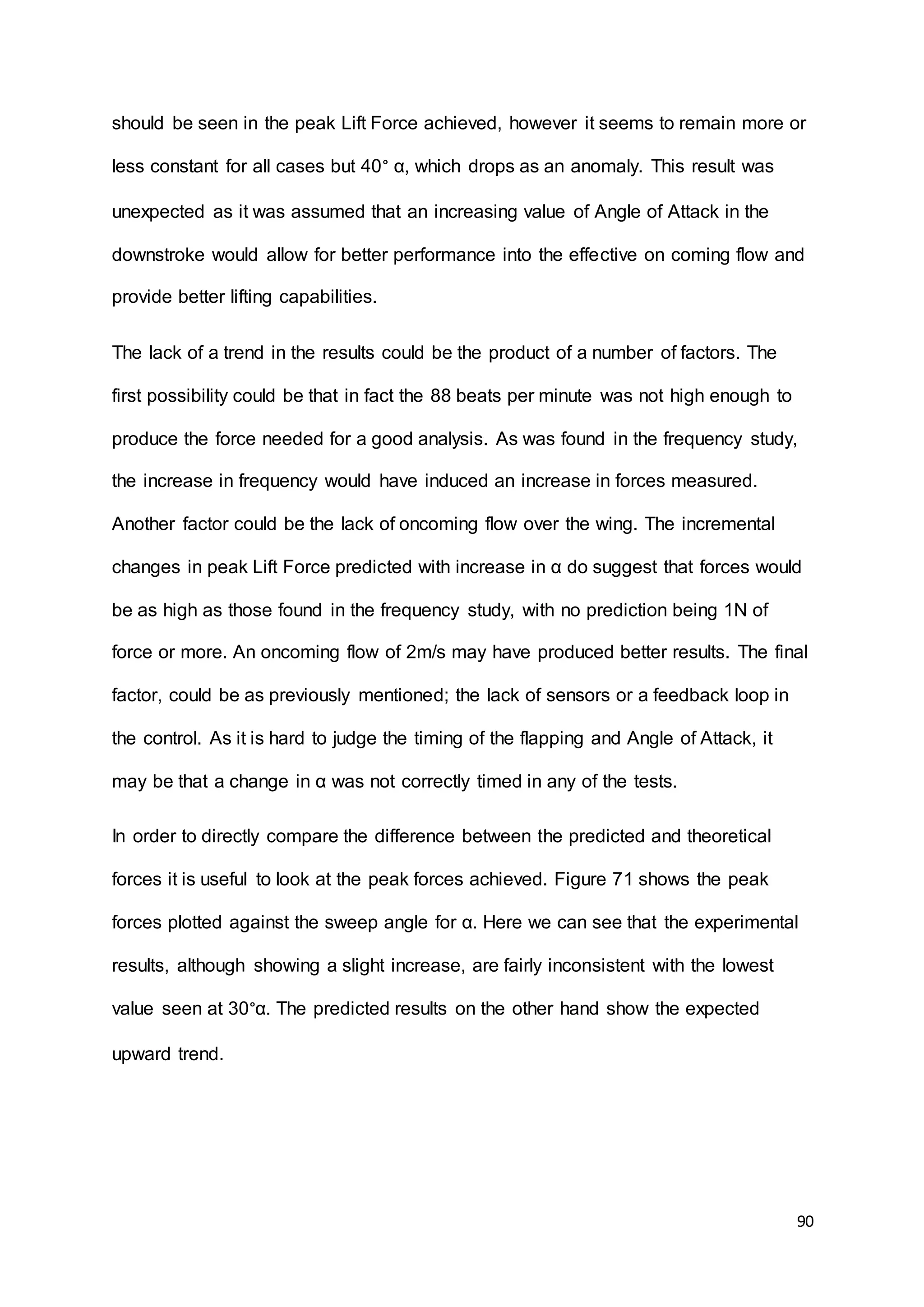

Figure 70 shows the plots of theoretical and experimental results for the testing of

increasing Angle of Attack. As much as possible, parameters were kept constant

across all testing with the same frequency, same conditions and the servos moving

the wings between positive and negative α at a uniform speed. Again as in previous

discussion over the theoretical results, the velocity applied in the equation for Lift

Force is not 0m/s which would be the true horizontal component of velocity on the

test rig wings. The freestream speed was again treated as 2m/s with the increase

induced by the wings flapping at 88 beats per minute. This allowed the aerodynamic

mechanisms and the motion of the wings to be accounted for in force calculations.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-88-2048.jpg)

![93

stroke with higher frequency. It goes without saying that with higher frequency, the

force generated is applied more regularly per minute than the lesser force at a lower

amount of beats per minute. In the design of a flapping wing air vehicle, possibly the

most essential factor in its success would be to match the frequency with the

characteristics of the wings to ensure enough lift for the required performance. Angle

of Attack of the wings in the stroke, although important to some degree is thought

would be more essential in generating thrust which was not a subject of this project.

In further work there are many more alterations and measurements that would be of

use to the development of flapping wing flight. However as a result of this project and

specifically the work done in testing the concept of the flapping wings, with internal

servos providing wing twist, the main additional investigation would be as follows:

Firstly the investigations carried out in the results of this project, would be carried out

in some form of airflow, or the test rig attached to a rotating arm of constant speed.

This would allow forces to be measured outside of the zero velocity condition and

would allow the exact parameters used in the theoretical calculations to be

controlled. A second study to be carried out would be into the propulsive force

generated by the wings and the effect of the Angle of Attack and frequency on the

thrust the wings generate. For work such as this, it may also be of interest to add

some form of flexible trailing edge towards the tip of the wing, which could enhance

the thrust created significantly. Lastly the alteration off the design to the two panelled

wing configuration of the Festo Smartbird [3] would allow for a comparison of inertial

forces. The two panelled wing by its nature should provide a better conservation of

momentum in the flapping wings, due to the panels flapping out of phase. Forces at

the end of the down stroke would likely be far less in amplitude, with the entire flap

cycle being much smoother without the rapid change in direction of the wings seen](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-93-2048.jpg)

![95

10. References

1. Andrew M. Mountcastle, Stacey A. Combes (2013) 'Wing flexibility enhances load-

lifting capacity in bumblebees', Proceedings B, 280(1759), pp. 1-2 [Online]. Available

at:http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/280/1759/20130531 (Accessed:

15/09/2015)

2. Sane, S.P.,Dickinson, M.H. (2001) 'The Control Of Flight Force By A Flapping Wing:

Lift And Drag Production', The Journal Of Experimental Biology, 204(JEB3400), pp.

2607-2626.

3. Festo (2011) Smartbird- Inspired by nature. [Online]. Available

at:http://www.festo.com/PDF_Flip/corp/smartbird_en/index.htm#/58/ (Accessed: 3rd

June 2015).

4. Festo (2013) BionicOpter - Inspired by Dragonfly Flight, Available

at:http://www.festo.com/net/SupportPortal/Files/248133/Festo_BionicOpter_en.pdf(A

ccessed: 3rd June 2015).

5. Festo (2015) eMotionButterflies - Ultralight flying objects with collective

behaviour,Available

at:http://www.festo.com/net/SupportPortal/Files/367913/Festo_eMotionButterflies_en.

pdf(Accessed: 3rd June 2015).

6. Lauri Poldre (2011) An interview with the engineer behind the man-made

SmartBird.,Available at: http://blog.grabcad.com/blog/2011/06/14/festo-

smartbird/ (Accessed: 4th June 2015).

7. Image Available from: http://www.festo.com/cms/en_corp/13165.htm

8. Nico Nijenhuis (2014) Clear Flight Solutions, Available

at:http://clearflightsolutions.com/ (Accessed: 4th June 2015).

9. Colin Jeffrey (2014) Robotic raptors look and fly like the real thing, Available

at:http://www.gizmag.com/flying-robot-raptor-birds-deter-nuisance-

flocks/33563/(Accessed: 4th June 2015).

10. Kyle Vanhemert (2014) Realistic Robo-Hawks Designed to Fly Around and Terrorize

Real Birds, Available at: http://www.wired.com/2014/08/realistic-robo-hawks-

designed-to-fly-around-and-terrorize-real-birds/ (Accessed: 4th June 2015).

11. Withers, P. C. An aerodynamic analysis of birds wings as fixed aerofoils. J. Exp.

Biol., 1981, 90, 143–162

12. Liu, T. , Kuykendoll, K. , Rhew, R., and Jones, S. Avian wing geometry and

kinematics. AIAA J., 2006, 44, 954–963.

13. BROWN, R.E., FEDDE, M.R. (1993) 'Airflow Sensors in the avian wing', Journal of

Experimental Biology, 179(66506), pp. 13-30.

14. Carruthers A.C.∗, Walker S.M., Thomas A.L.R., Taylor G.K. (2009) 'Aerodynamics of

aerofoil sections measured on a free-flying bird', Part G: J. Aerospace

Engineering,224(AERO737), pp. 855-864.

15. Bilo, D. Flugbiophysik von Kleinvögeln. I. Kinematik und Aerodynamik des

Flügelabschlages beim Haussperling (Passer domesticus L.). Z. vergl. Physiol.,

1971, 71, 382–454

16. Brill, C., Mayer-Kunz, D. P., and Nachtigall,W.Wing pro- file data of a free-gliding

bird. Naturwissenschaften, 1989, 76, 39–40.

17. Heather Howard (2014) Falconsong Studios, Available

at:http://www.falconsongstudios.com/?page_id=844 (Accessed: 9th June 2015).

18. Andrew A. Biewener (2011) 'Muscle function in avian flight: achieving power and

control', Integration of muscle function for producing and controlling

movement,366(1570), pp. 3-15 [Online]. Available

at:http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/366/1570/1496 (Accessed: 9th June

2015).

19. Image available from: http://www.birdsnways.com/wisdom/ww19eii.htm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-95-2048.jpg)

![99

12. Appendix: Dissertation Proposal: Bio-inspired

Flying Machines

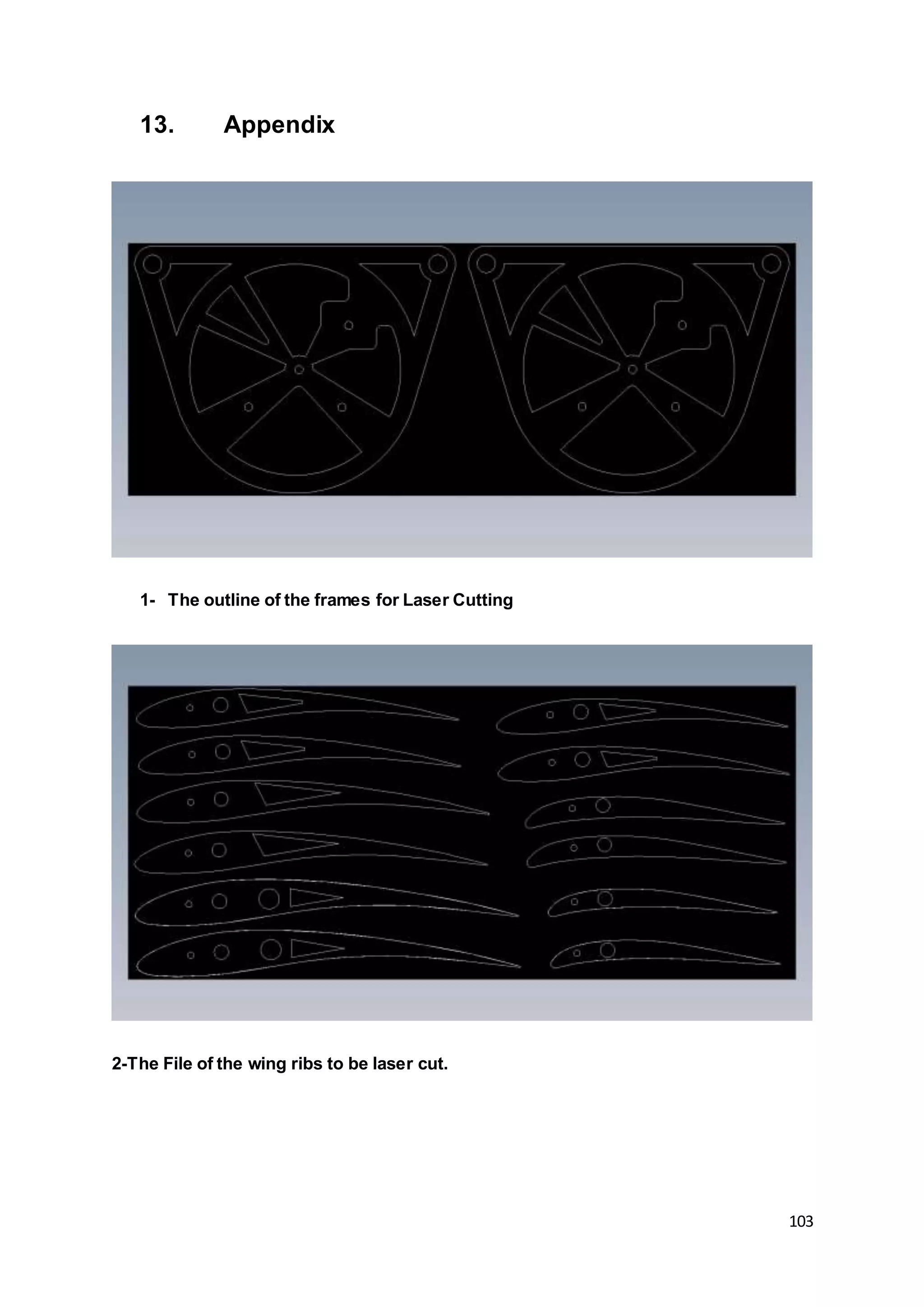

1. Introduction and Background to the Project

There is currently a fast increasing interest in bird and insect flight and how this

could be interpreted into a mechanical flying machine, more specifically in the form

of a UAV (unmanned air vehicle). Potential for such vehicles has been identified in a

number of sectors, most notably in the military market. With development of stealth

technology and radar being in a constant battle of development, a new form of

stealth is being considered, in the form of ‘bird or insect like’ vehicles. These would

be small and disguised to look as their counterparts in the natural world making them

very hard to detect visually and by radar. Lessons have already been learn for the

current generation of small UAV’s as birds and insects have naturally evolved to

operate in similar Reynolds number regimes [1].

Many attempts have been made to achieve flapping wing flight as it has been a

dream of man-kind for century’s to fly like a bird resulting in many ornithopter

attempts and to this day models are still being produced for hobbyists, some

powered by elastic bands, others powered by electric motors. However perhaps

the most significant step forward in bird like flight is the FESTO Smartbird, based

on a gull (Figure 1). This uses flapping with a servo to actively twist the wing

based on sensor readings for torsion of the wing, load on the motor and motor

position. Other vehicles have also been produced drawing inspiration from other

areas such as hummingbirds, dragonflies and other insects, however most of

these are much smaller and the end result is not as convincingly real.

Nonetheless, some of these have also provided major leaps forward in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8e899637-7cdd-4647-87b4-d35770687fda-160727153421/75/Dissertation-Final-Version-99-2048.jpg)