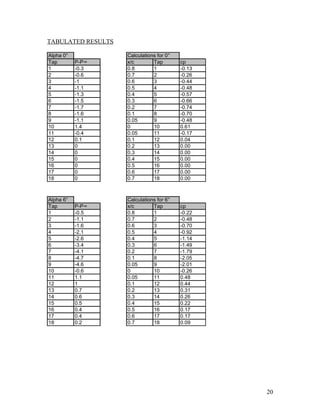

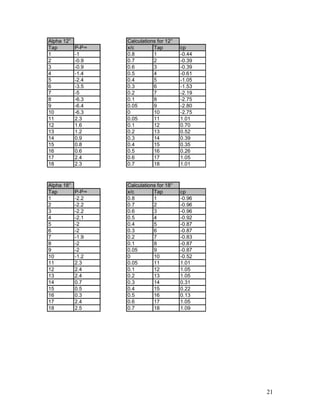

The document details a lab experiment conducted on an airfoil using a subsonic wind tunnel to measure pressure coefficients at various angles of attack. Data was collected under different conditions, yielding reliable results at 0° and 6° angles while 12° and 18° provided inaccurate readings due to possible experimental errors. The report includes theoretical background, methods, calculations, and a thorough analysis of the collected data.