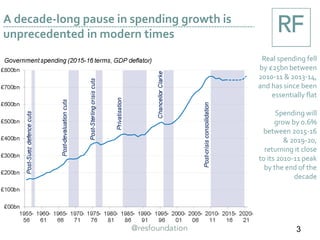

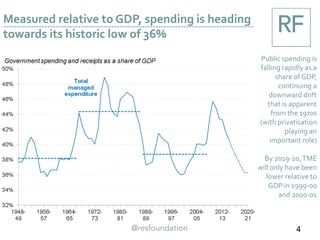

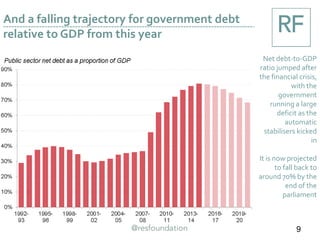

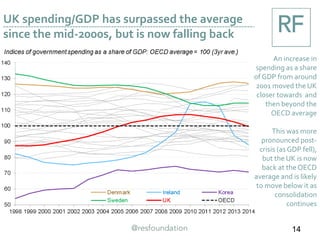

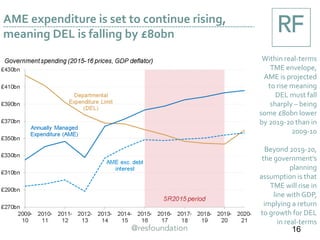

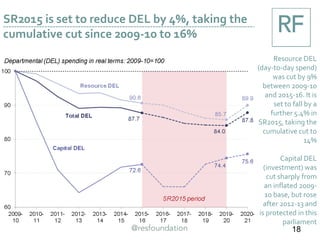

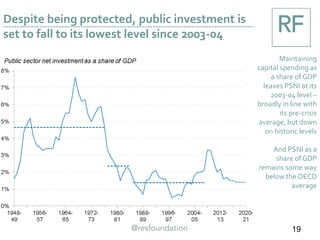

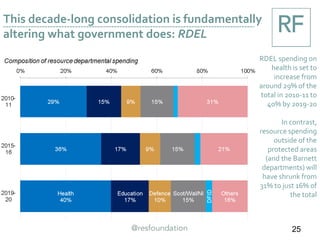

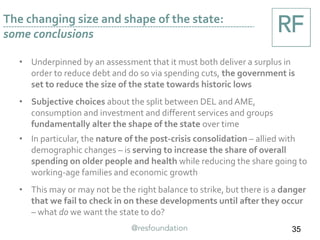

- Government spending has been essentially flat since 2010, growing by just 0.6% between 2015-16 and 2019-20, returning it close to 2010 levels. Public spending is falling as a share of GDP towards historic lows.

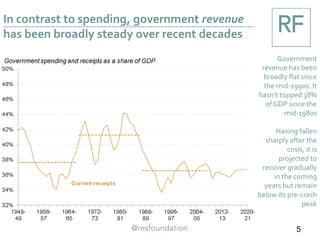

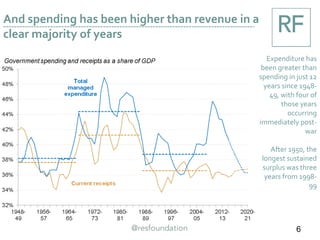

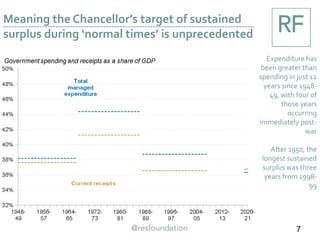

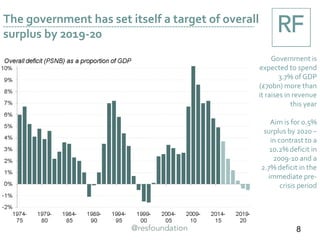

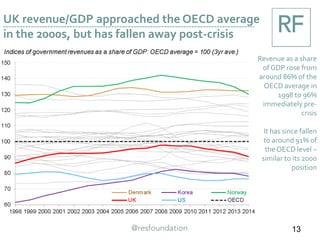

- In contrast, government revenue has remained broadly steady as a share of GDP over recent decades, hovering between 36-38%. The government aims to achieve a budget surplus of 0.5% by 2020 through spending cuts rather than tax increases.

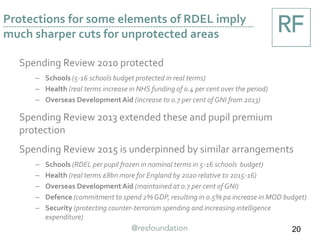

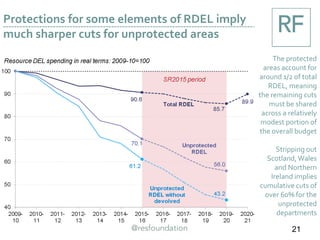

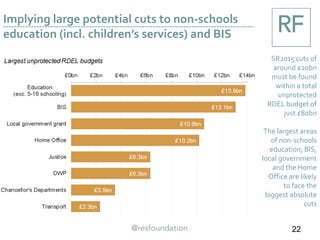

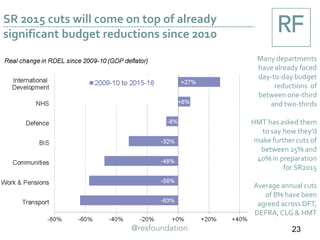

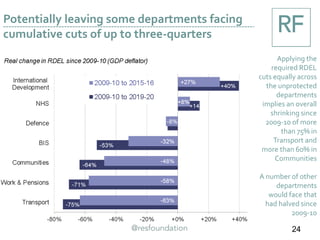

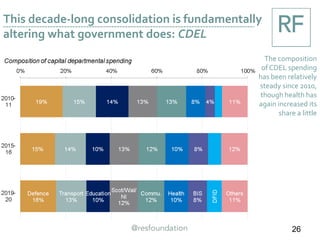

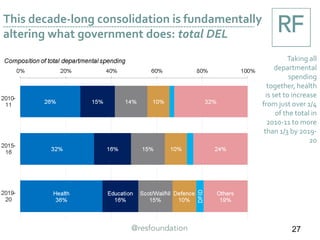

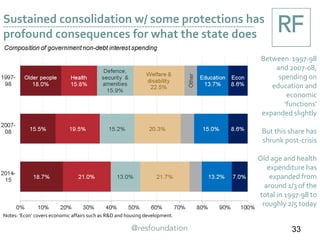

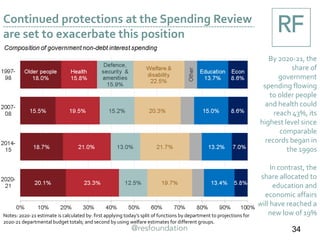

- Spending cuts have fallen disproportionately on "unprotected" departments beyond health, schools, overseas aid and defense, with potential cuts of over 60% for some departments since 2009-10. This is fundamentally altering what the government does