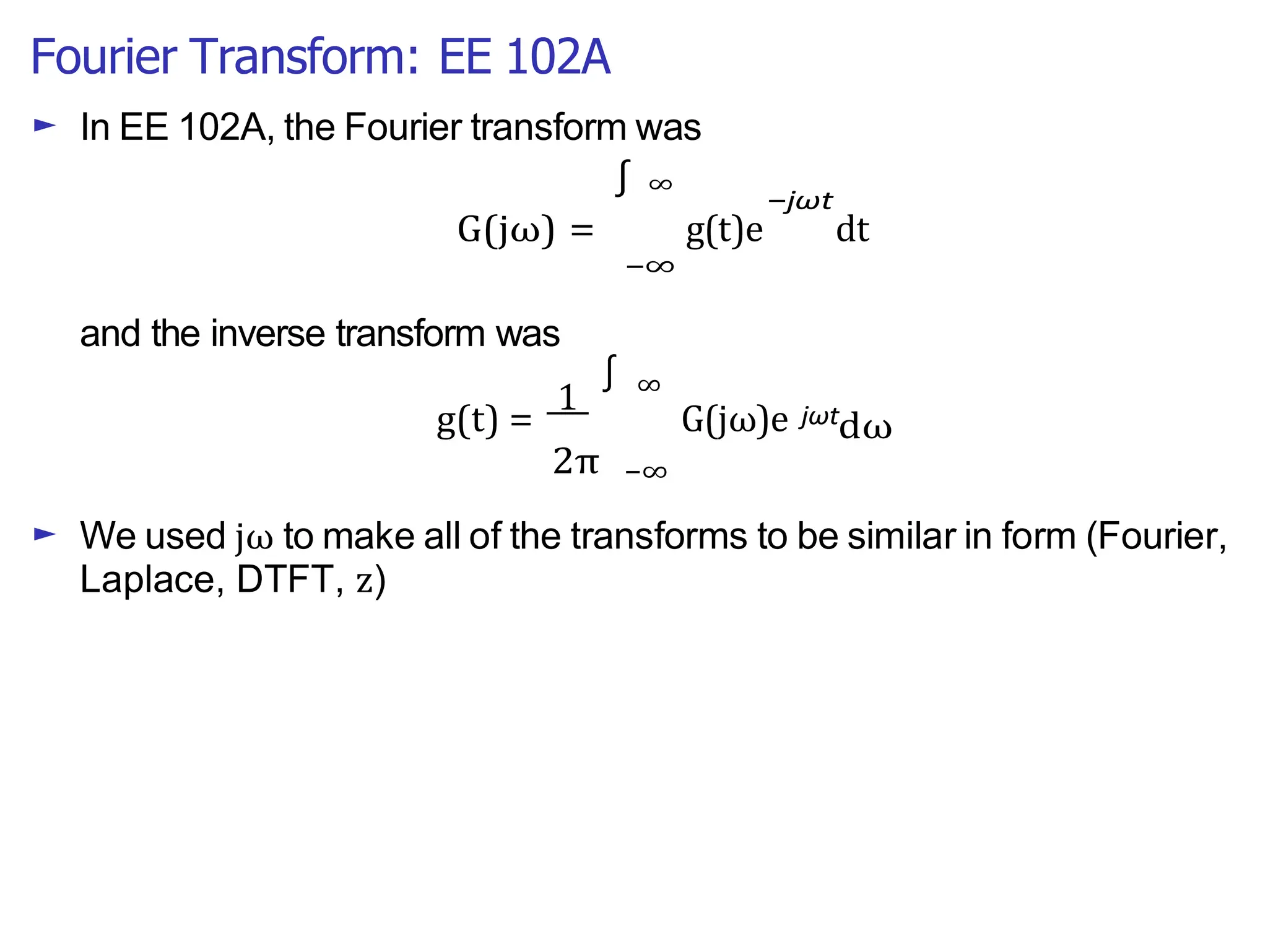

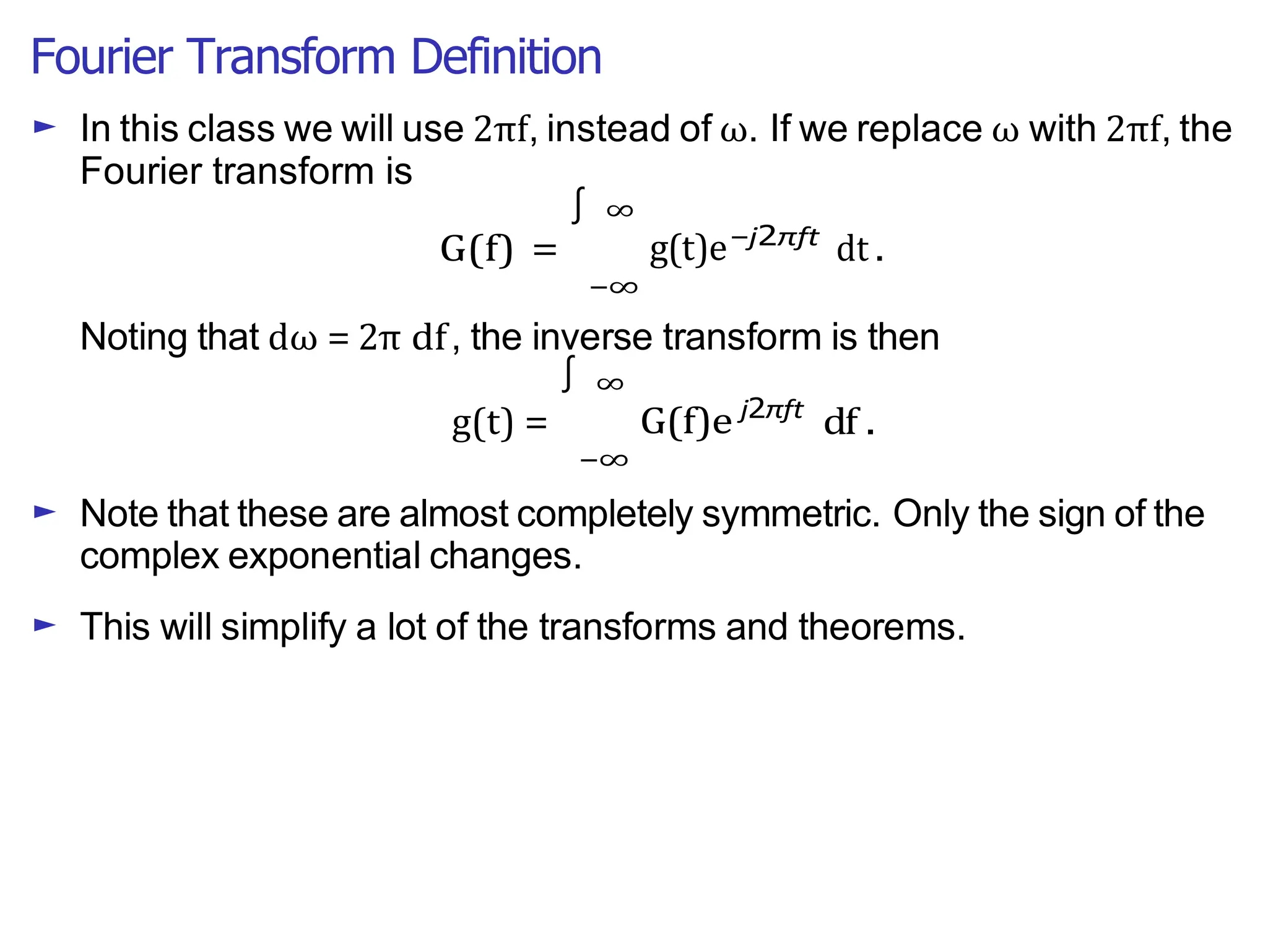

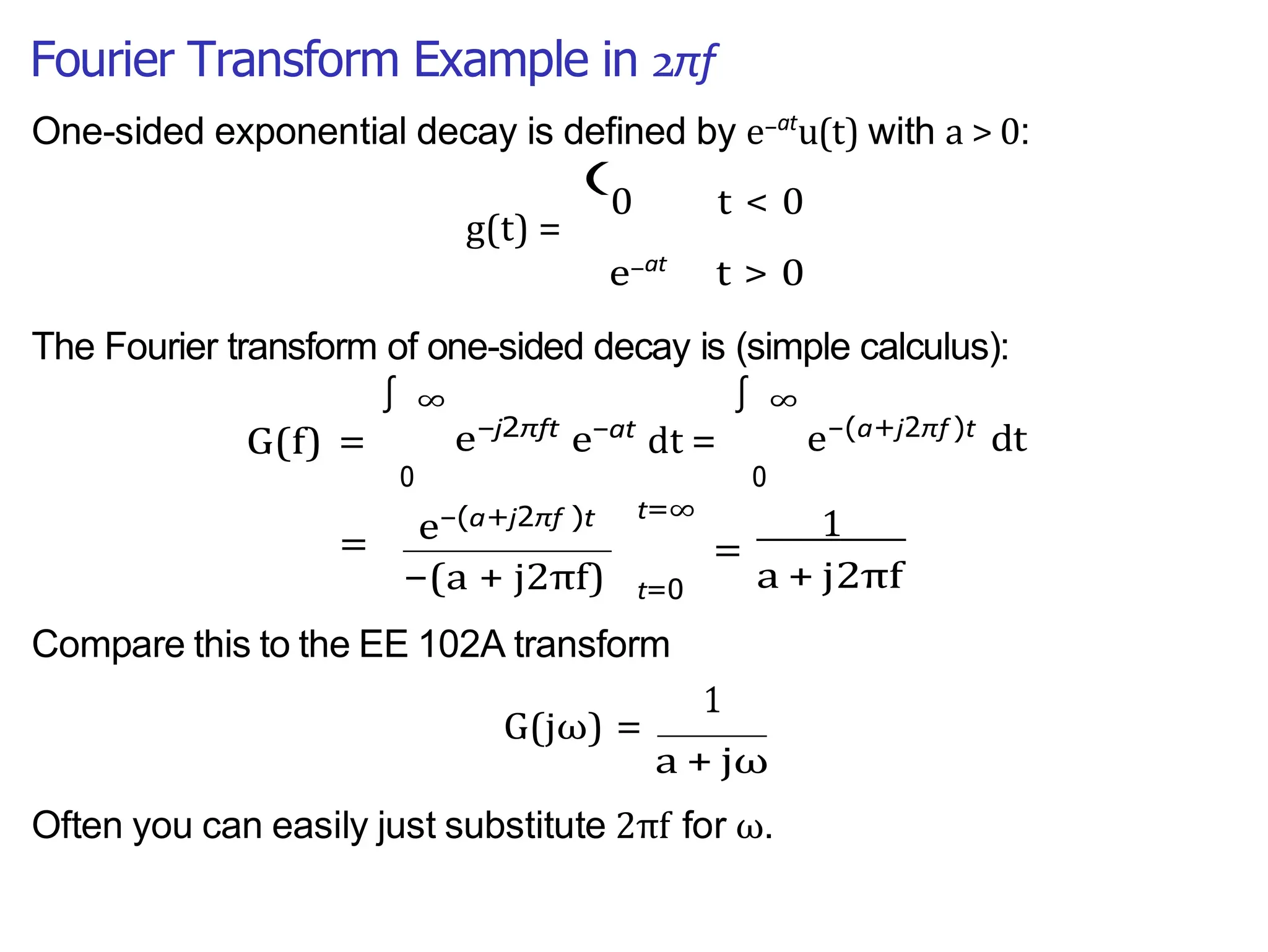

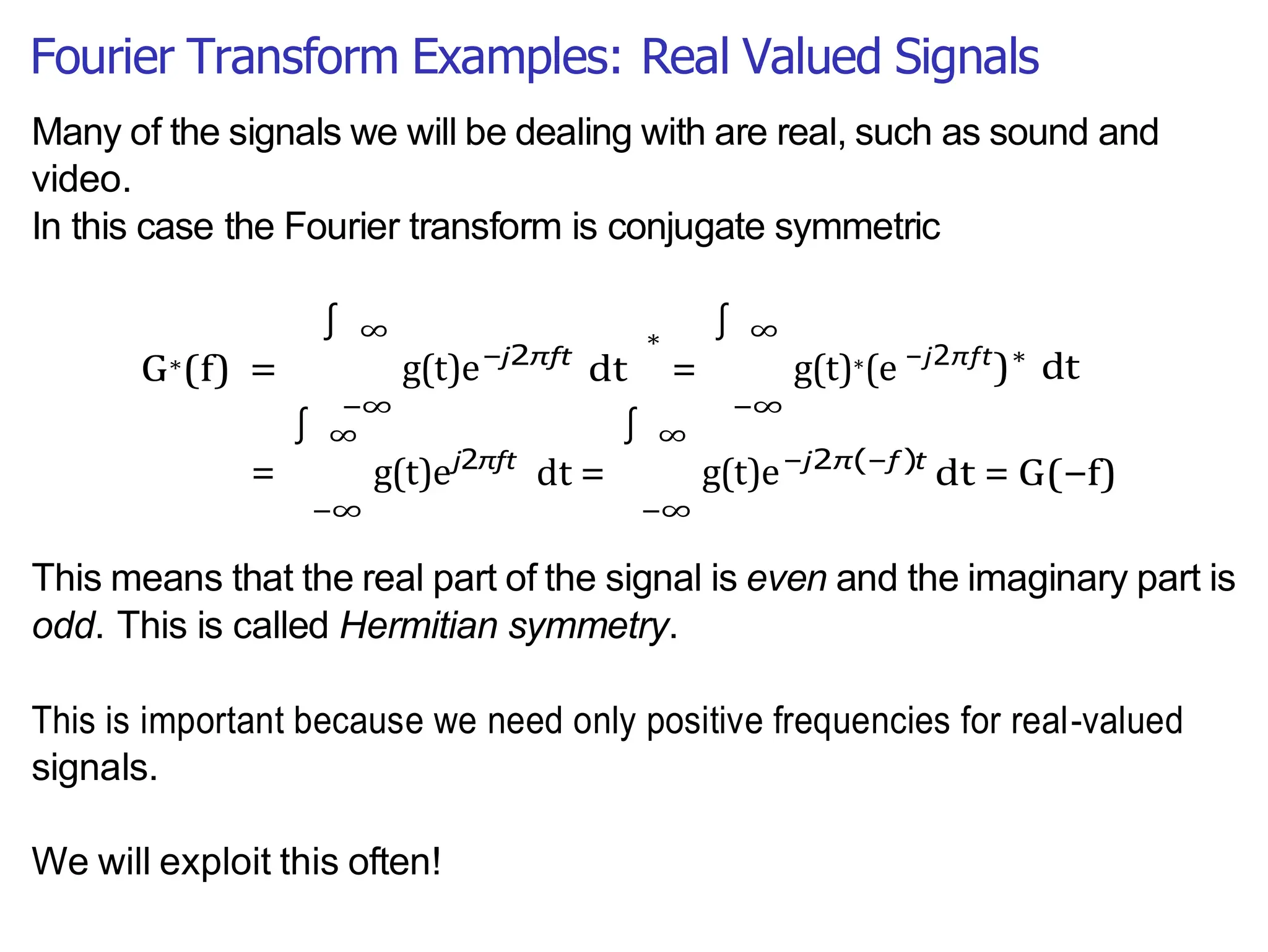

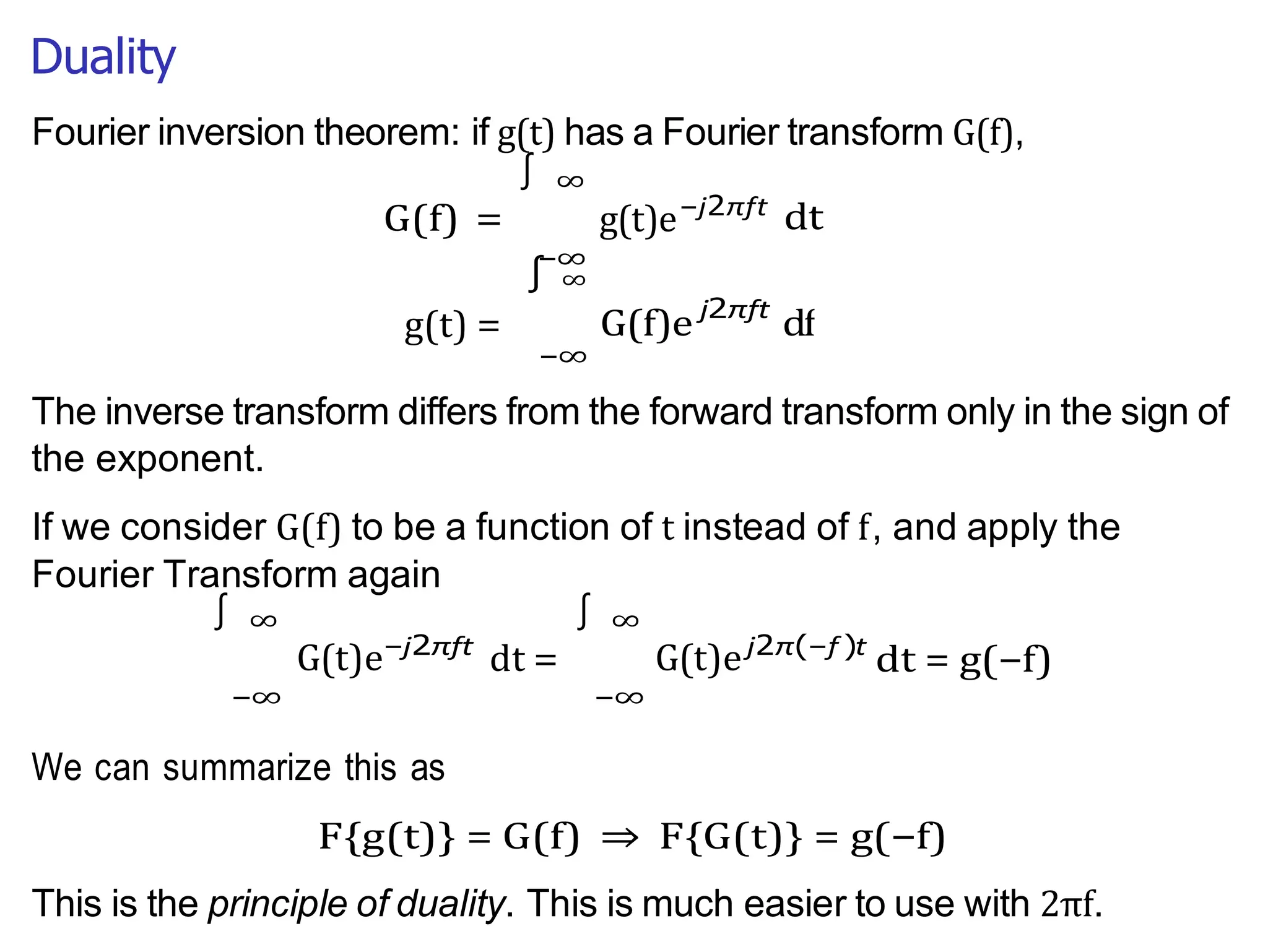

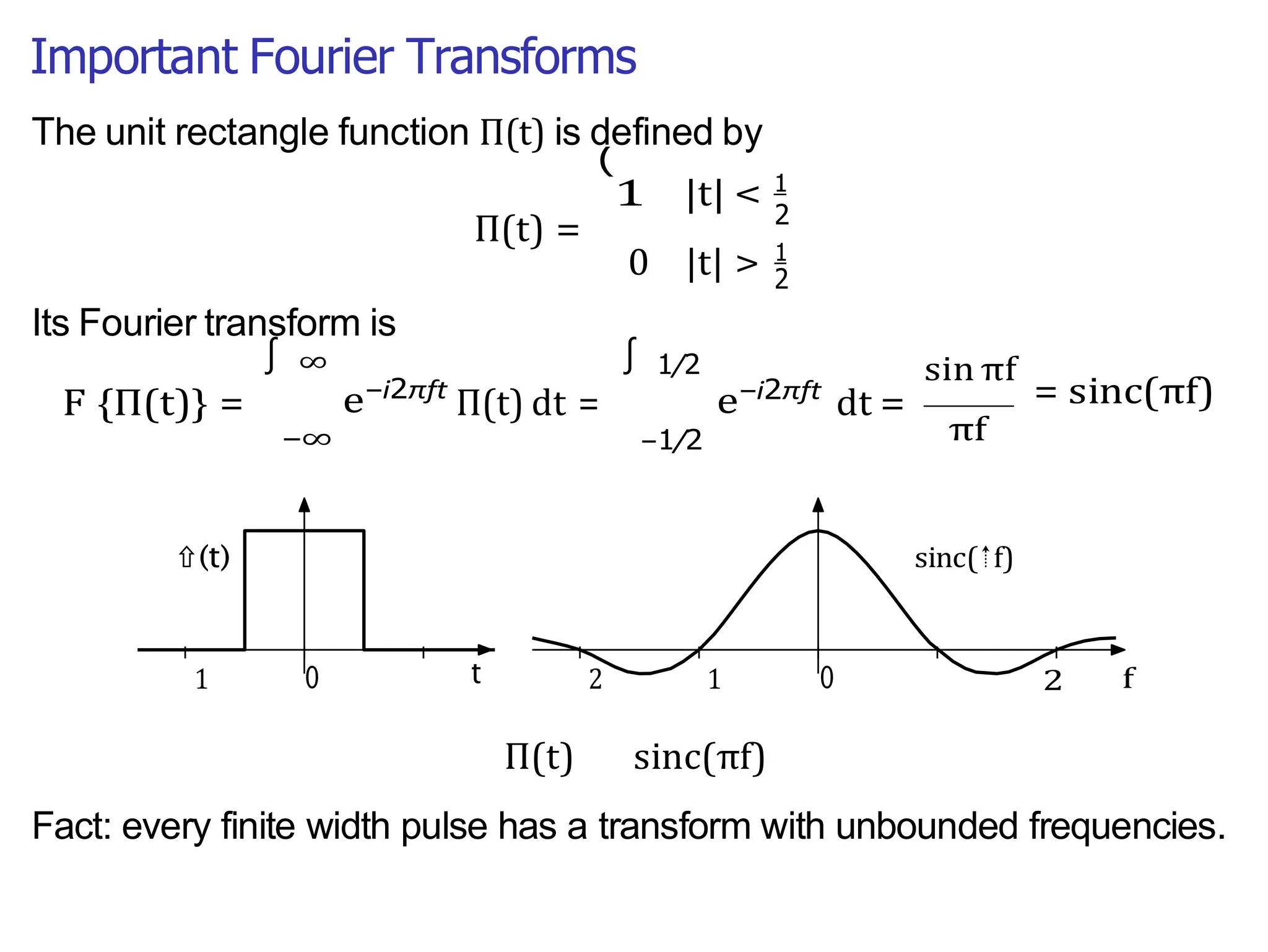

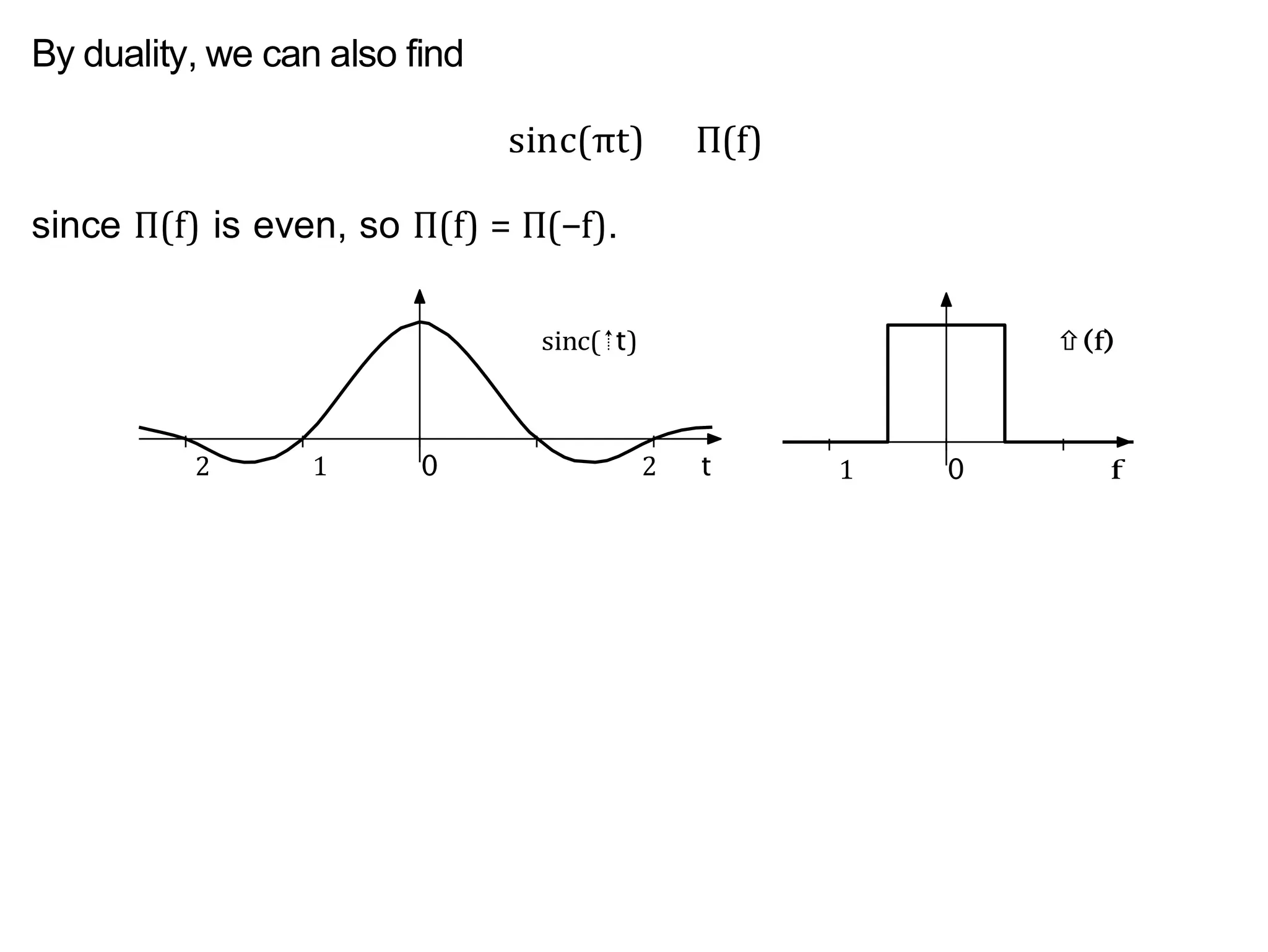

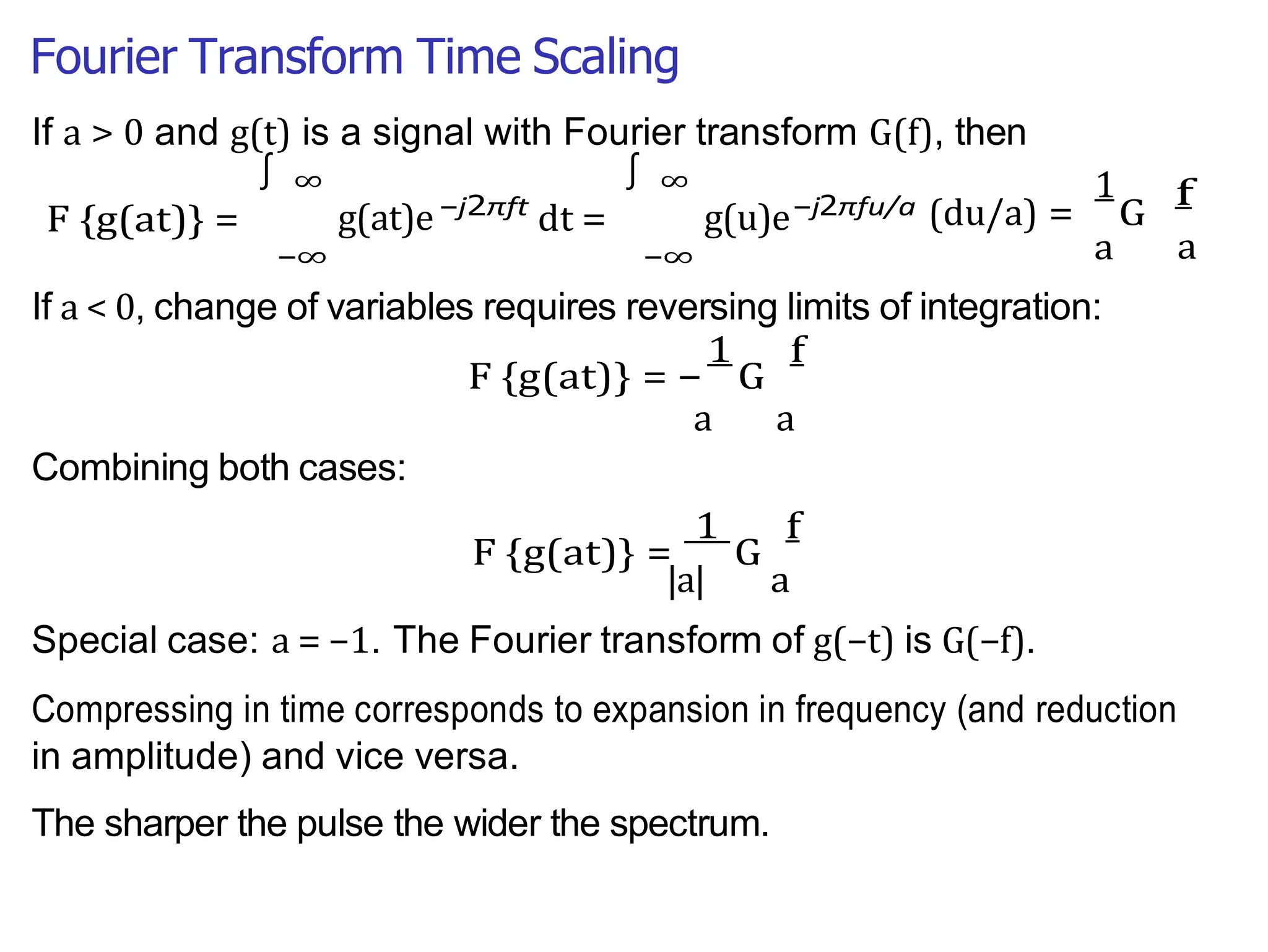

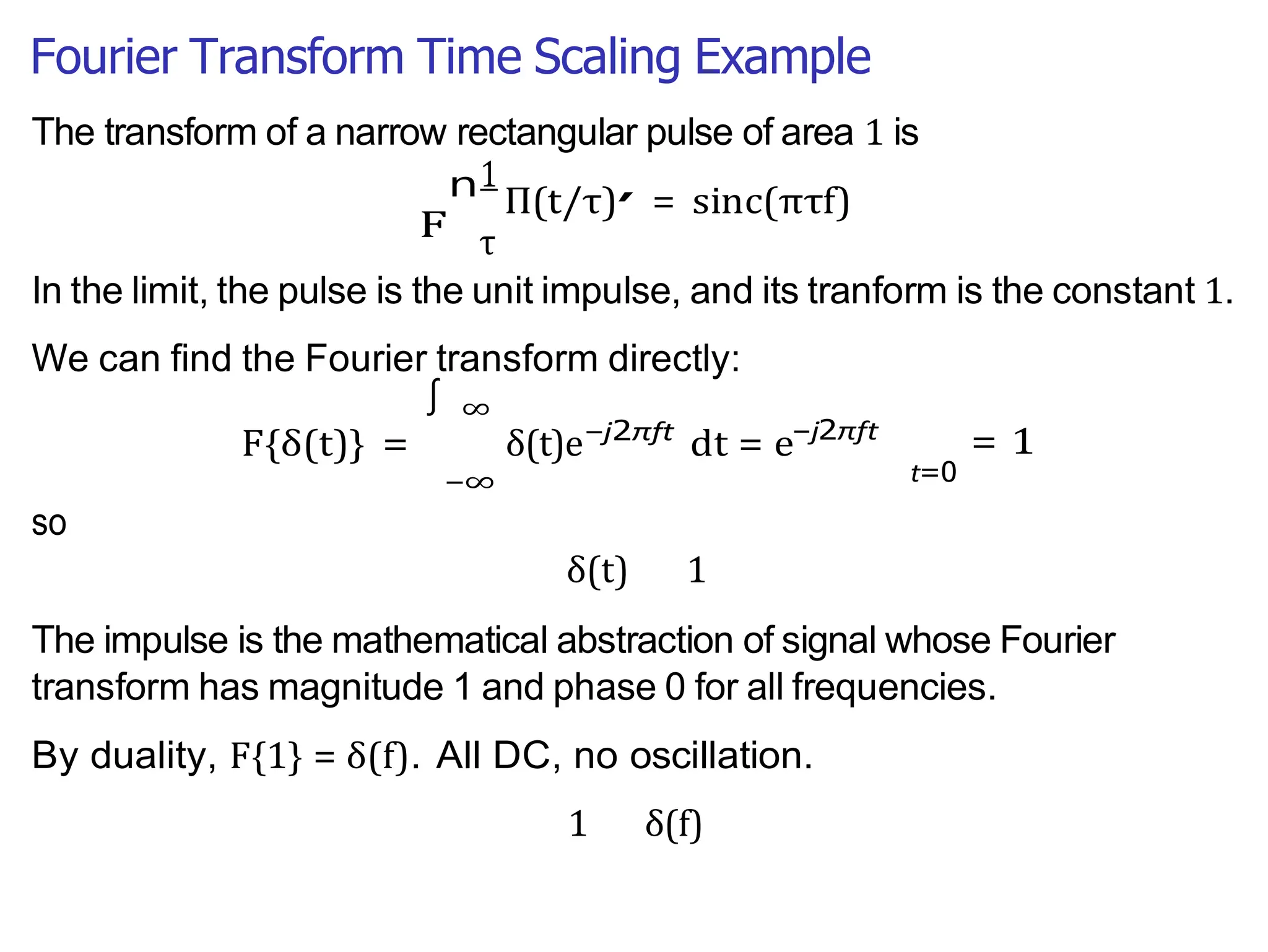

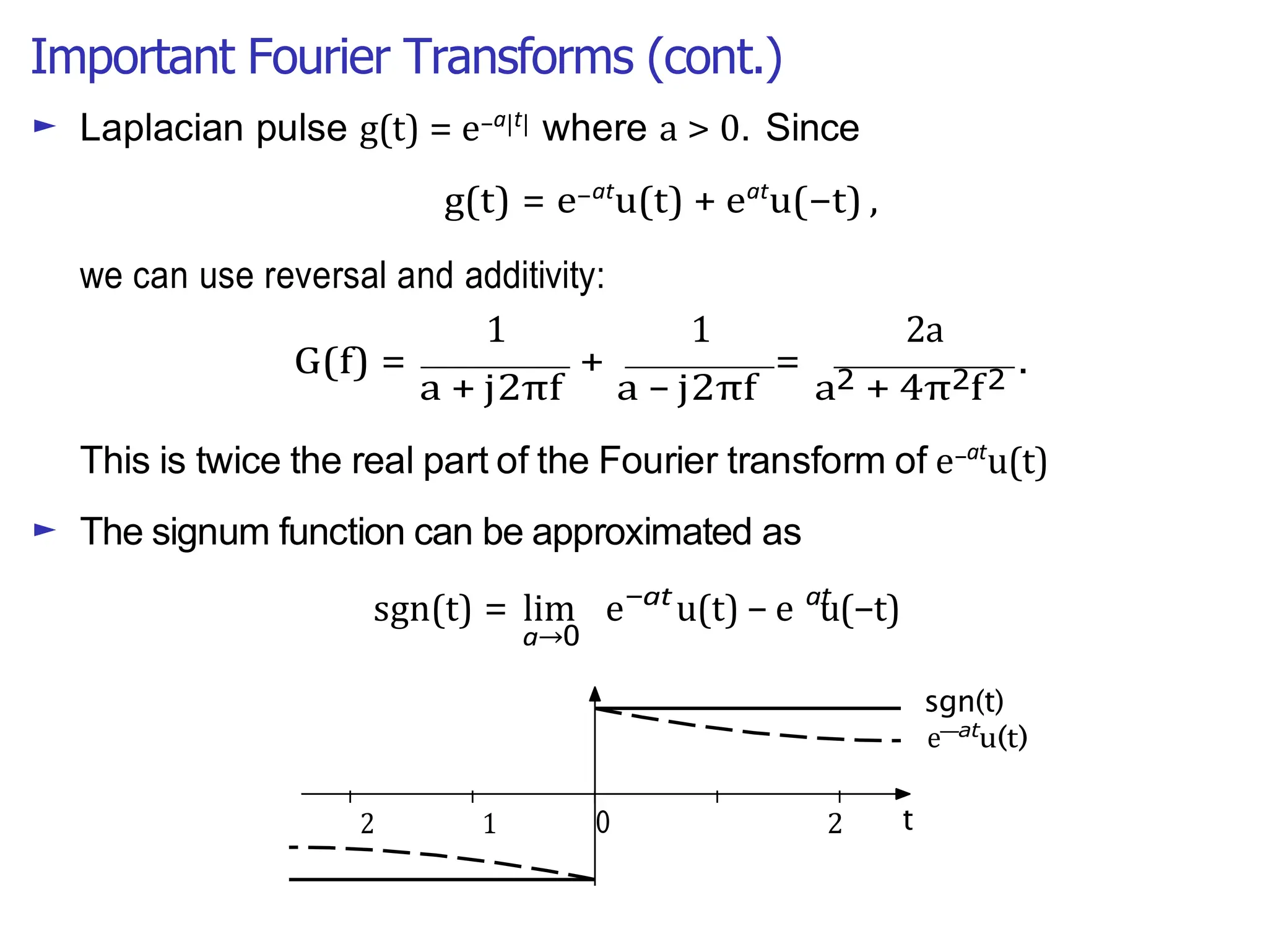

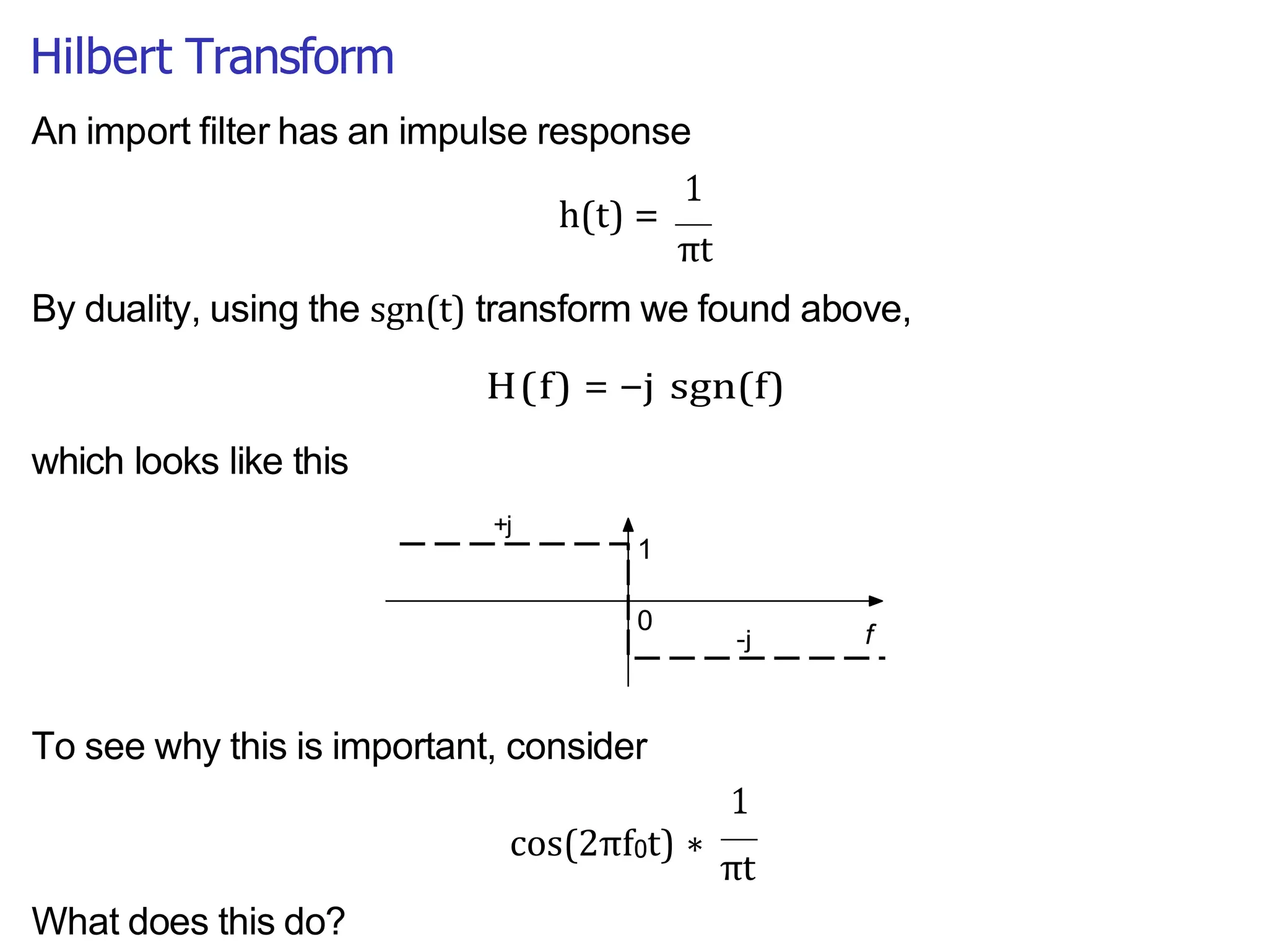

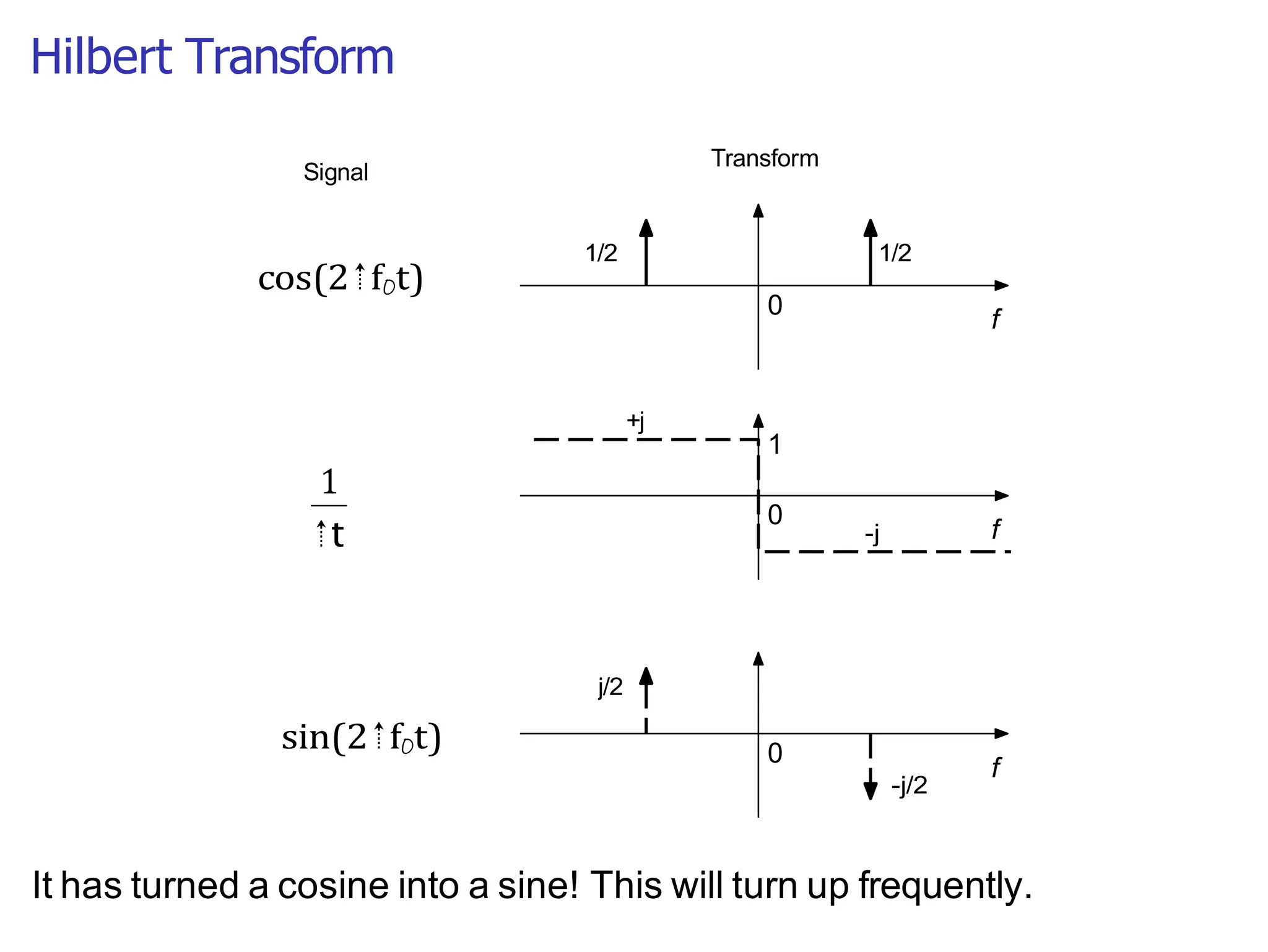

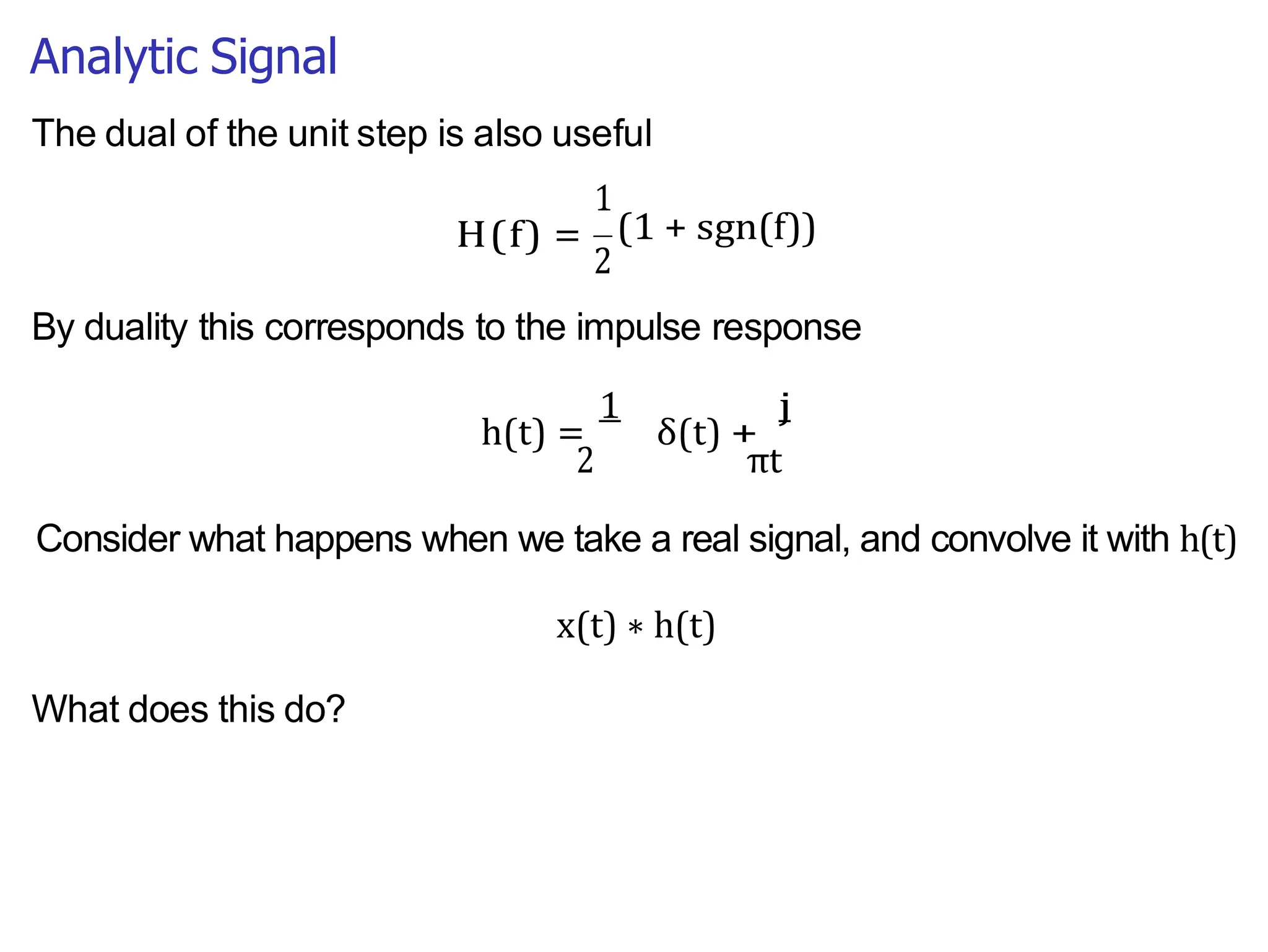

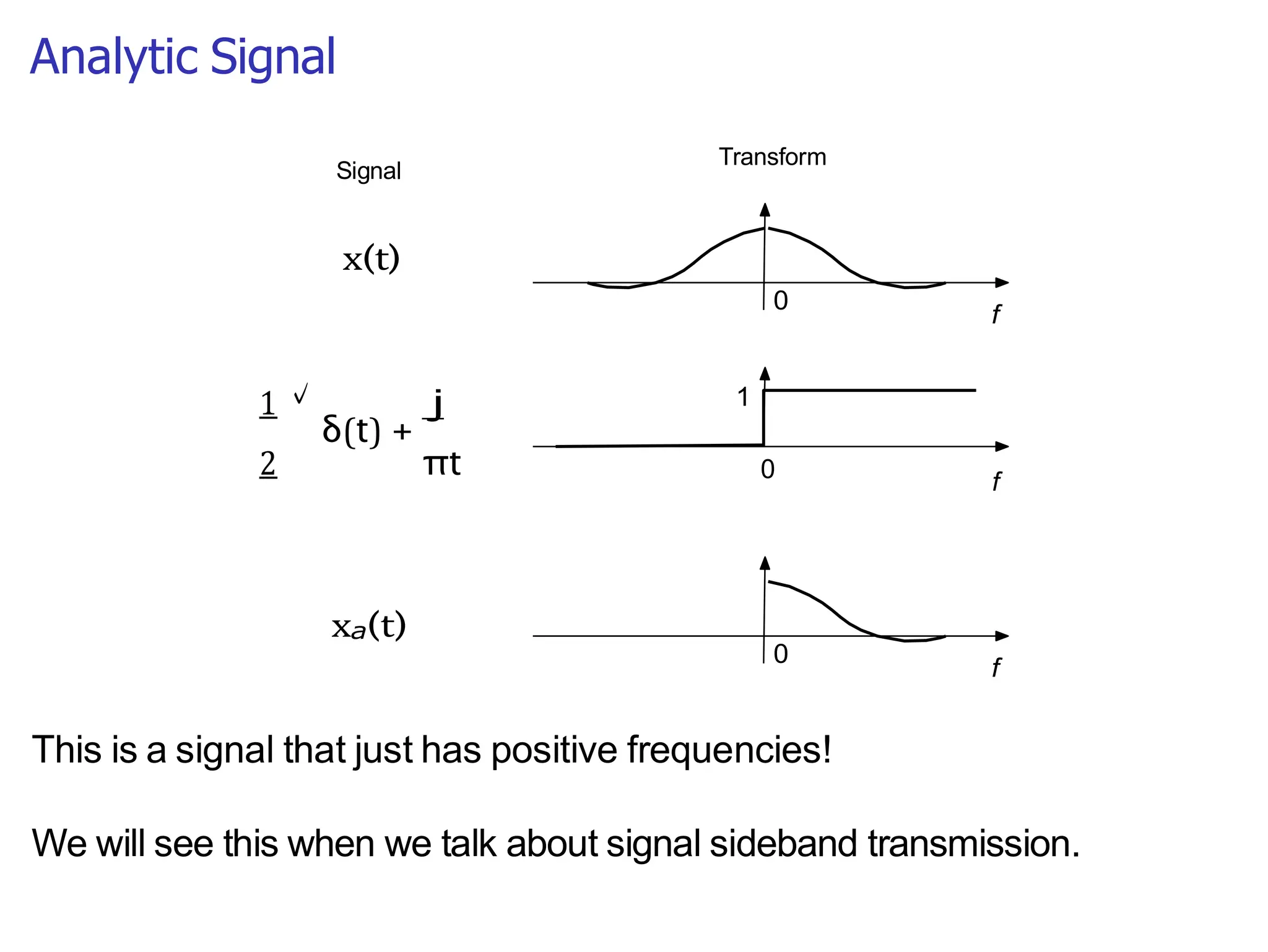

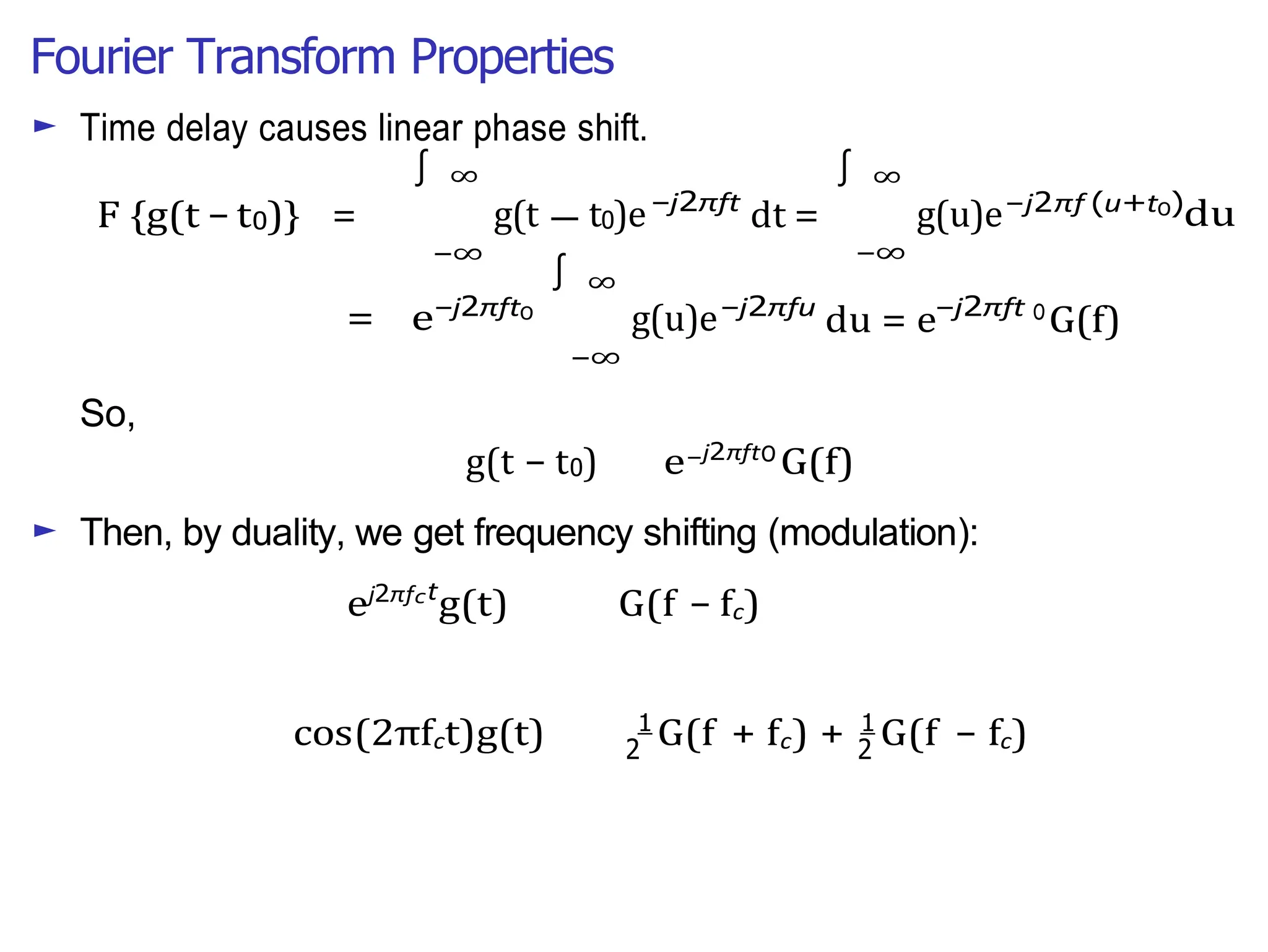

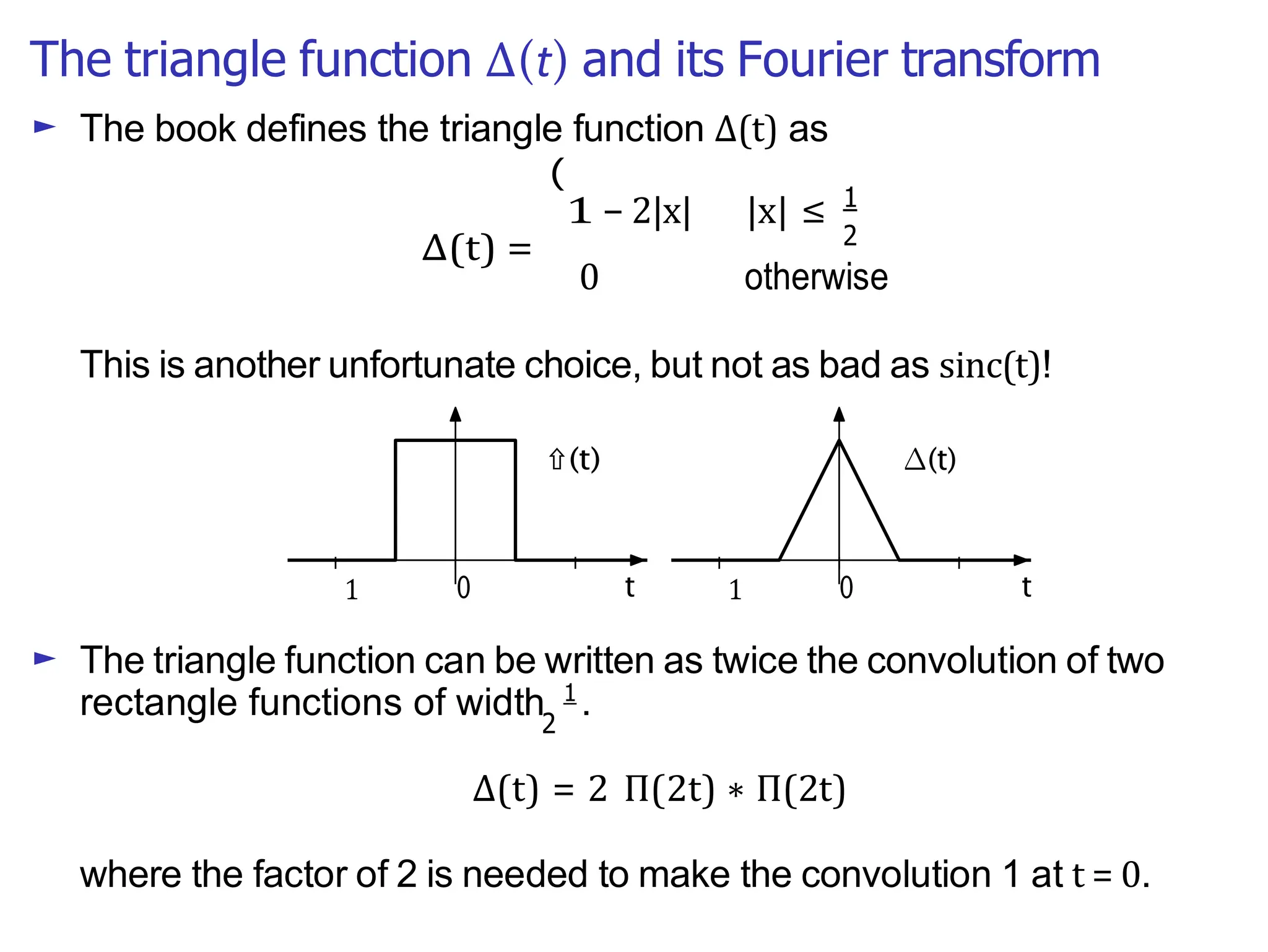

Lecture 4 covers the Fourier transform in the context of signals and systems, emphasizing its definition, properties, and applications. It distinguishes between frequency representations using 2πf instead of ω, and discusses important theorems and examples including the Hilbert transform and analytic signals. Additionally, it highlights modulation techniques and their relevance to communication channels.