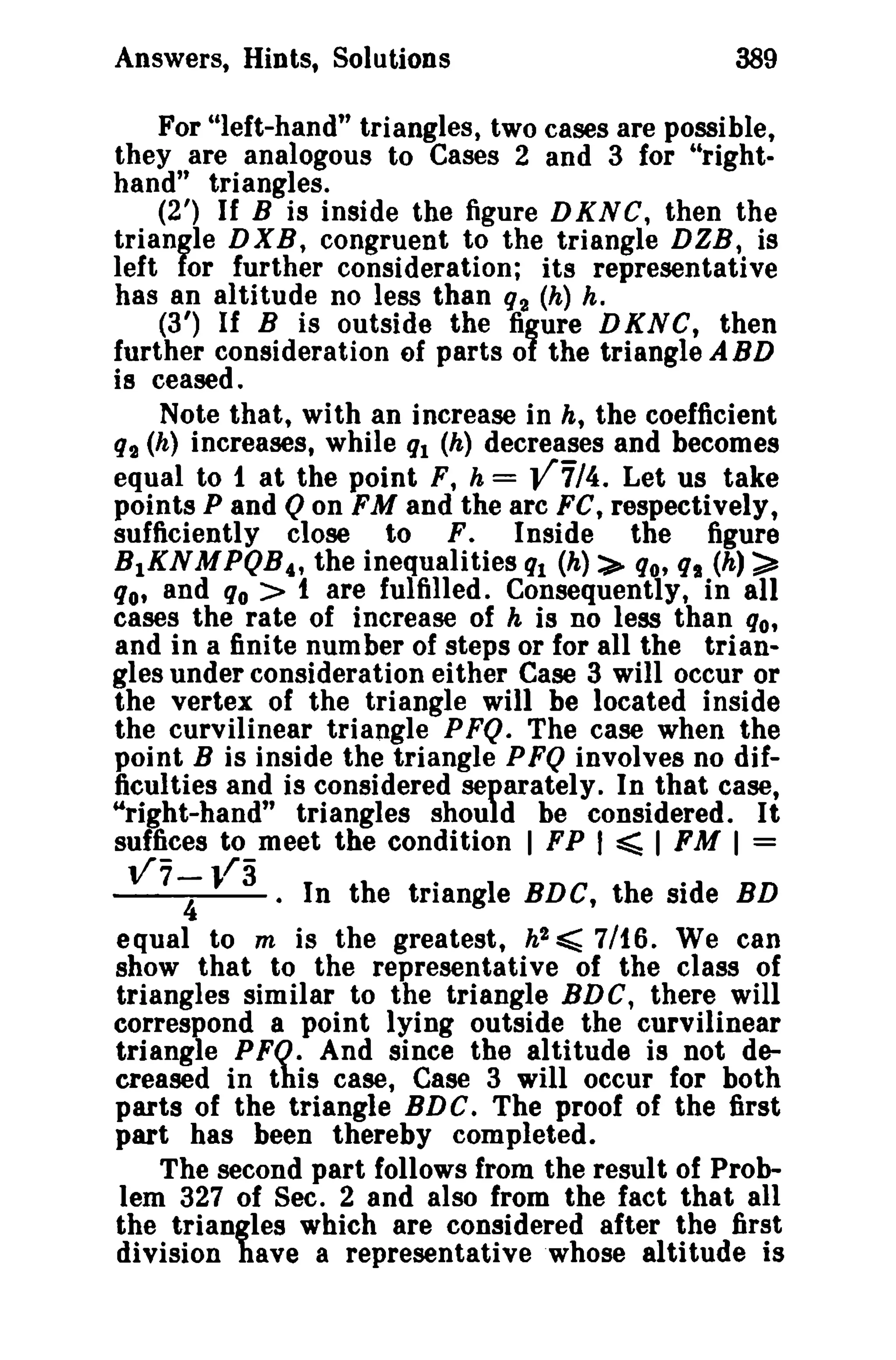

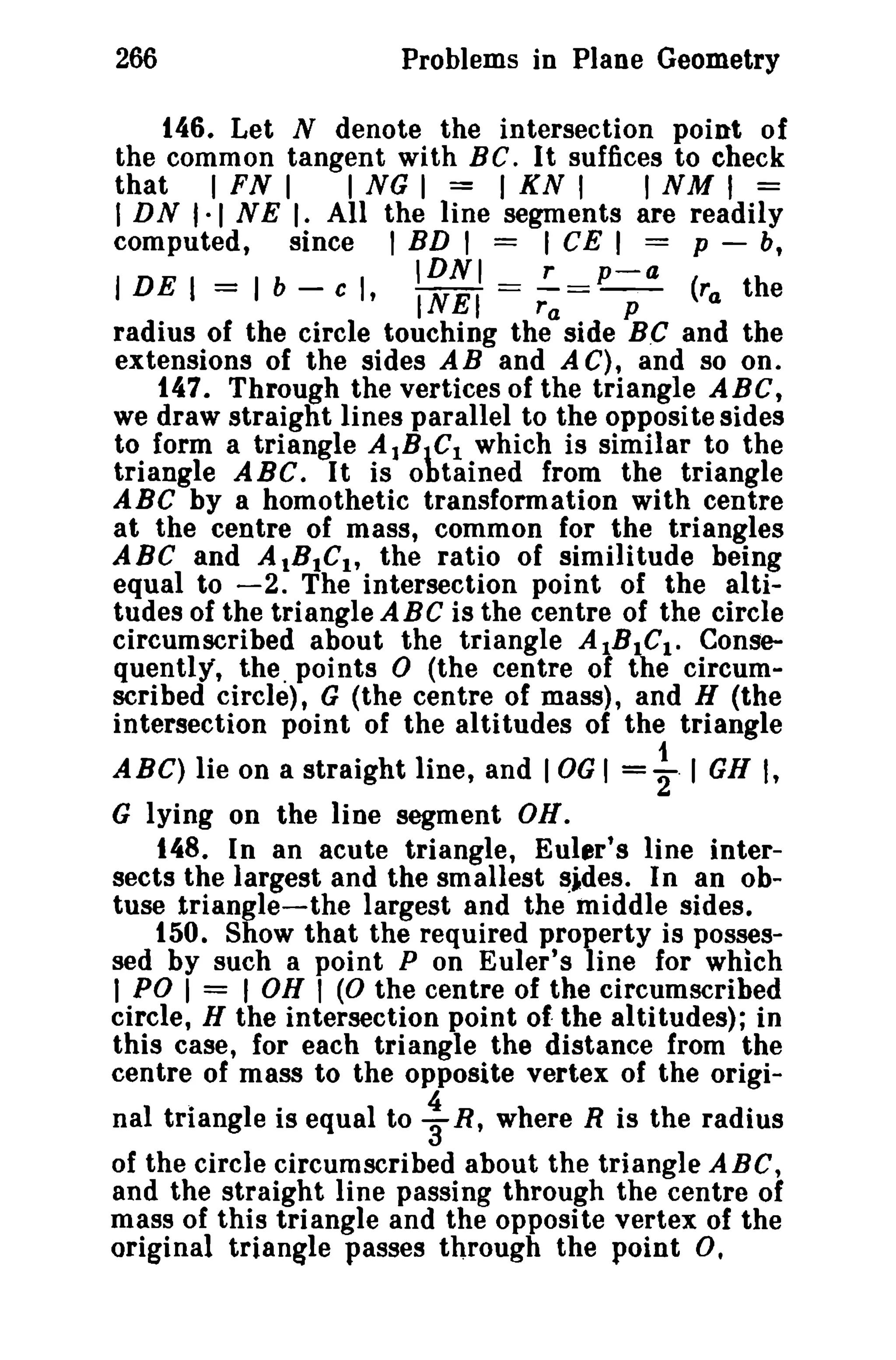

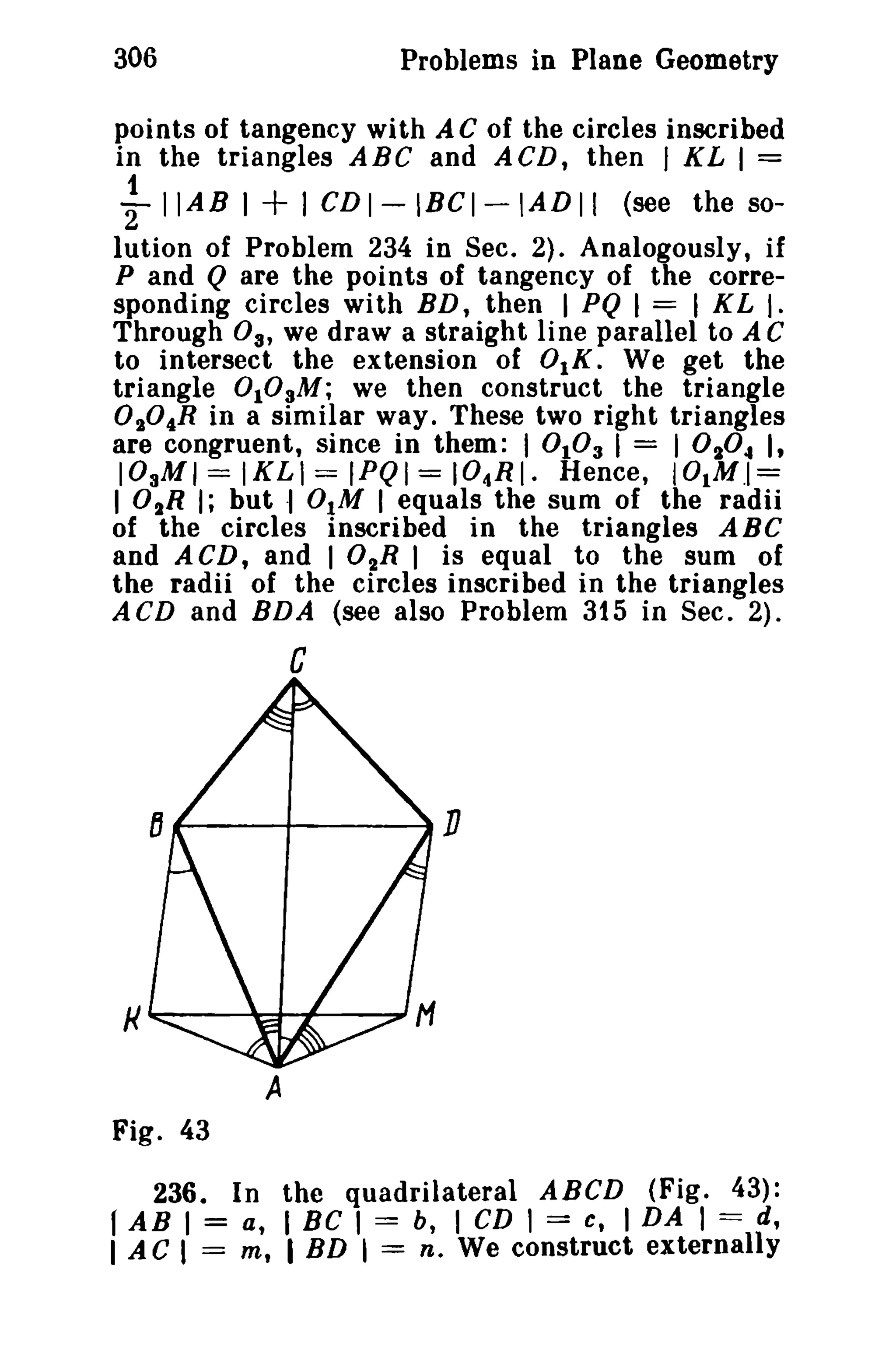

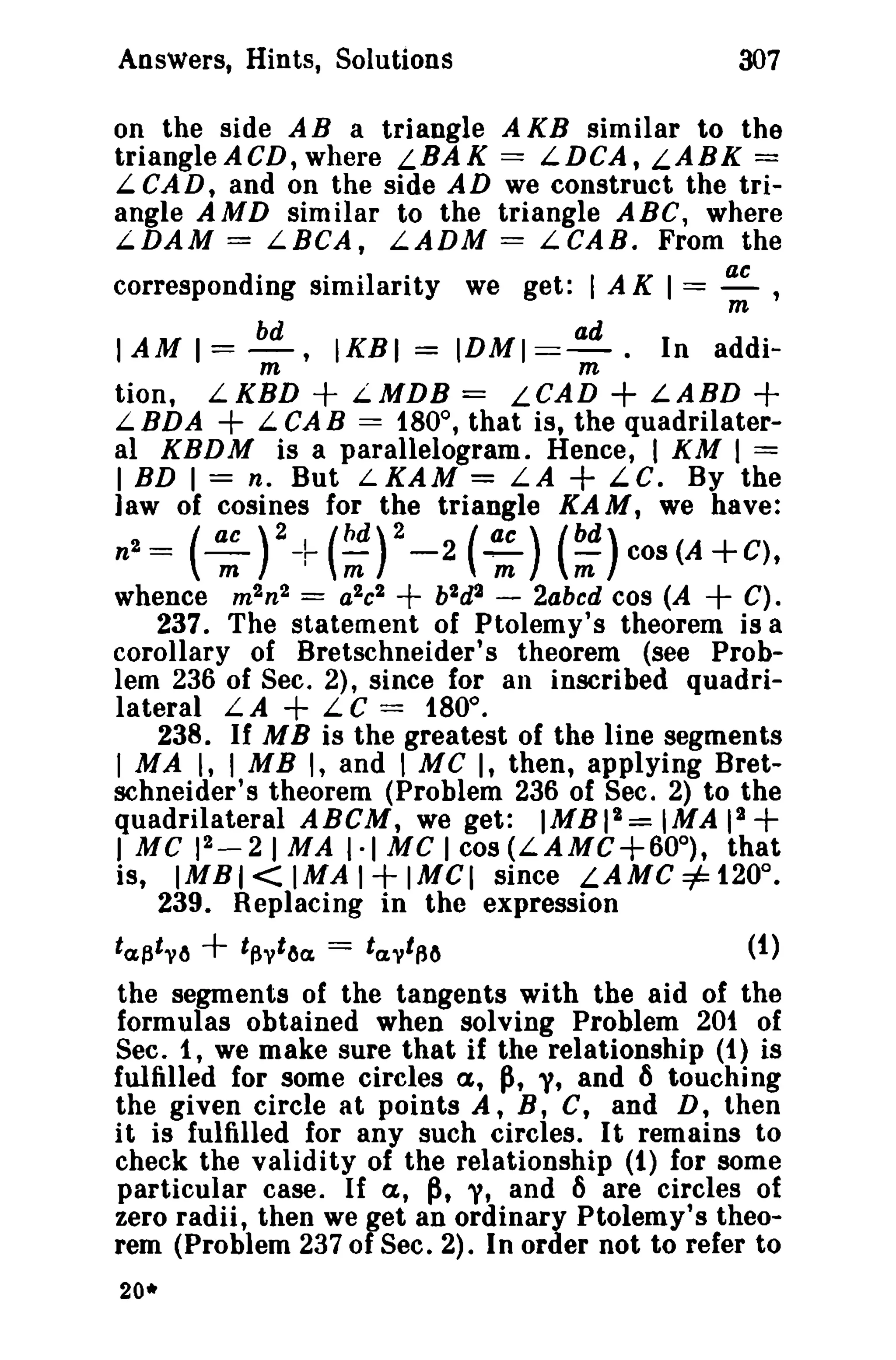

This document is a translation of a revised Russian book on geometry problems, designed for schoolchildren and teachers. It includes over 600 plane geometry problems, with varying levels of difficulty, and provides hints and detailed solutions for many problems. The book emphasizes the elegance of elementary techniques in geometry, encouraging critical thinking and understanding beyond standard exercises.

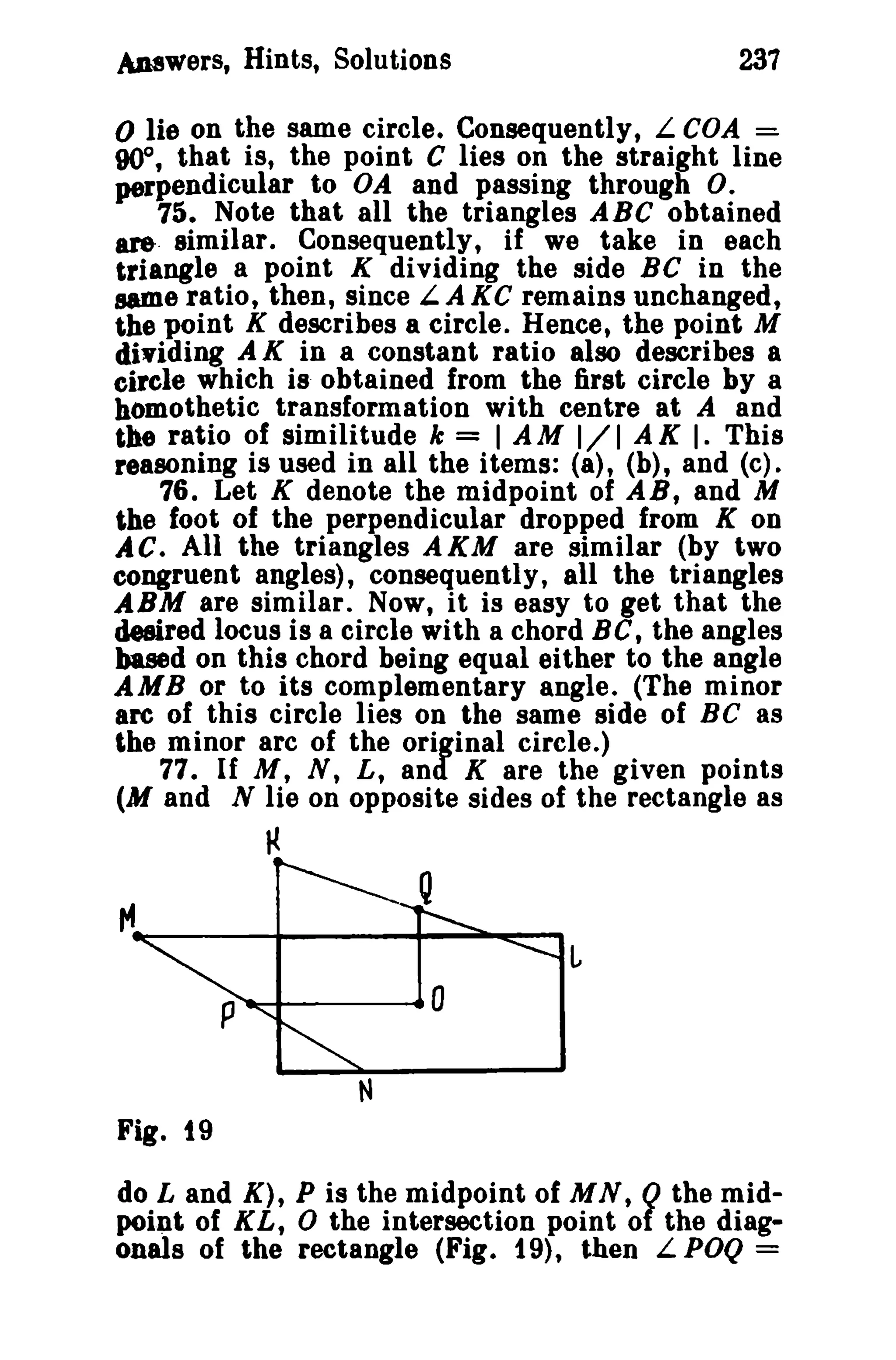

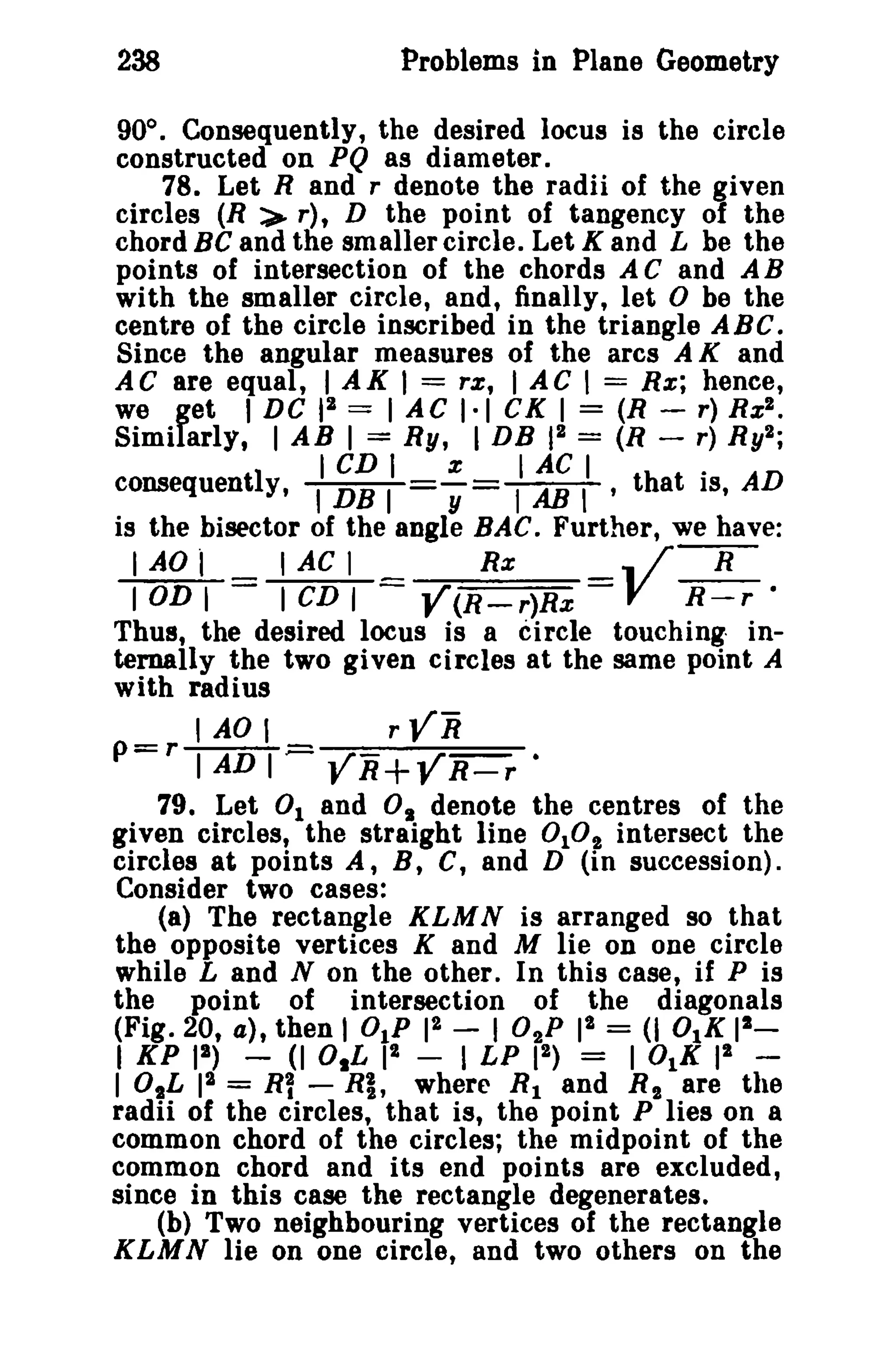

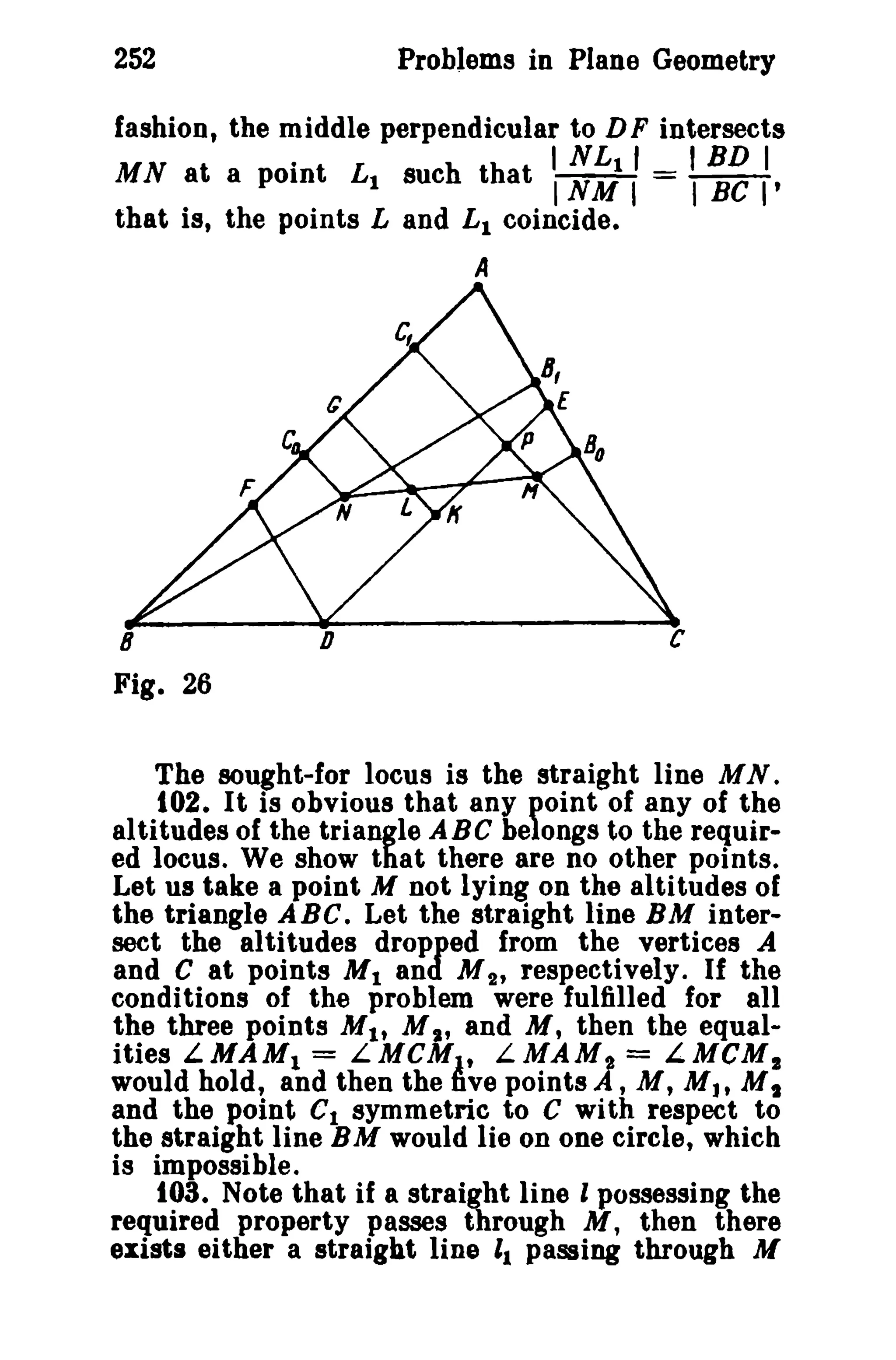

![Sec. f. Fundamental Facts 5t

where I AC I = a, IAB I, IAD I = PIAB I·

An arbitrary circle is described through A

and B, CM and DN being two tangents to

this circle (M and N are points on the circle

lying on opposite sides of the line AB).

In what ratio is the line segment AB divided

by the line MN?

236. In a circumscribed quadrilateral

ABeD, each line segment from A to the

points of tangency is equal to a, and each

line segment from C to the points of tangency

is b. What is the ratio in which the

diagonal AC is divided by the diagonal

BD?

237. A point K lies on the base AD of the

trapezoid ABeD. such that IAK I =

A IAD I. Find the ratio IAM I : I MD I,

where M is the point of intersection of the

base AD and the line passing through the

intersection points of the lines AB and CD

and the lines BK and AC.

Setting A = tin (n = 1, 2, 3, .], di-vide

a given line segment into n equal parts

using a straight edge only given a straight

line parallel to this segment.

238. In a right triangle ABC with the

hypotenuse AB equal to c, a circle is constructed

on the altitude CD as diameter.

Two tangents to this circle passing through

the points A and B touch the circle at points

M and N, respectively, and, when extended,

intersect at a point K. Find I MK I.

239. Taken on the sides AB, Be and CA

4*](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-140921124347-phpapp02/75/SHARIGUIN_problems_in_plane_geometry_-54-2048.jpg)

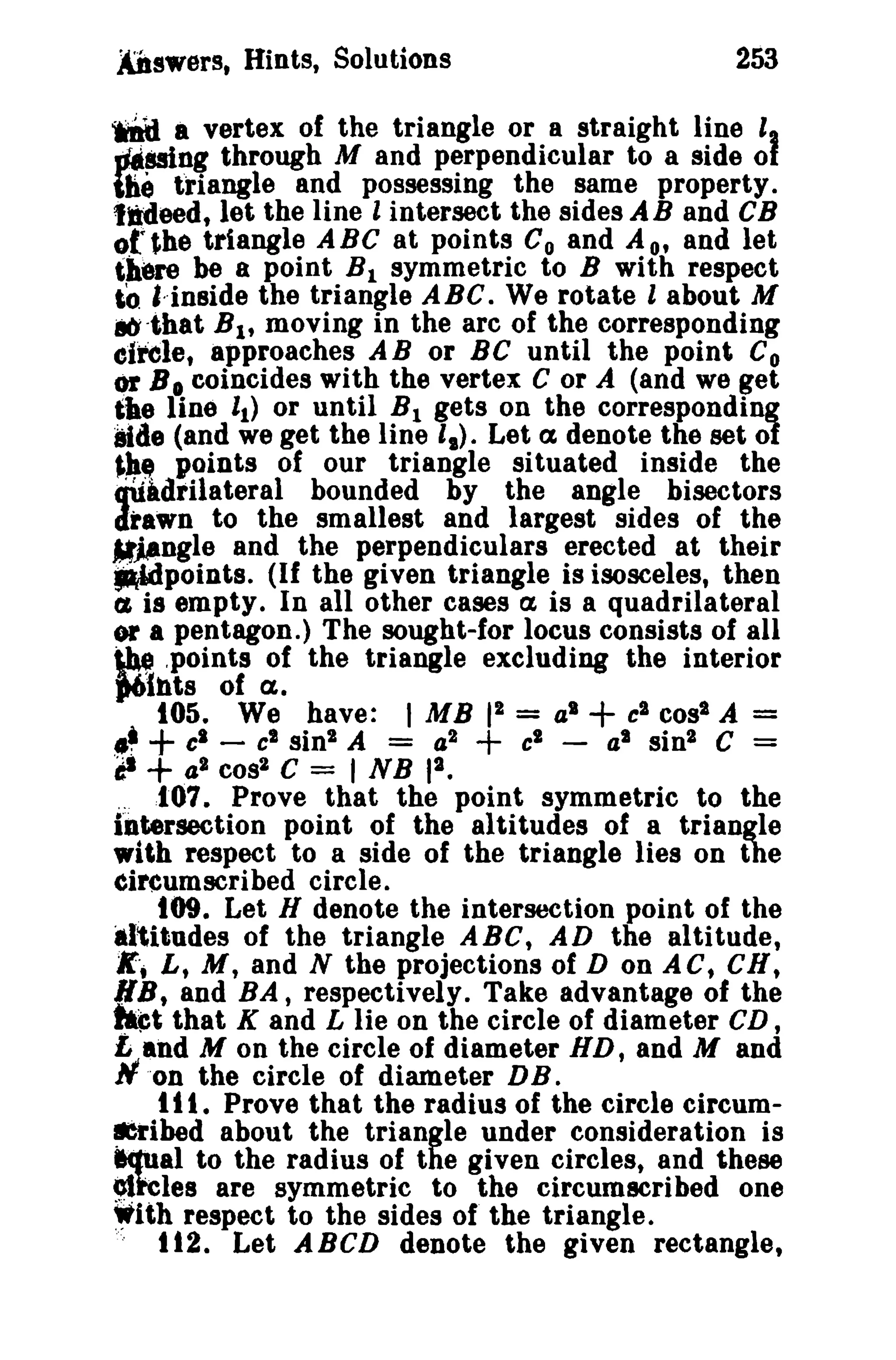

![164 Problems in Plane Geometry

tt5. a2(V2- i). 116. tJ cos (a.+~) a sin (a.+~)

. cos (2a.+1') , COB(2a + 6> •

a.

1 2 cos 3'+3

117. T a (b-a cos a.) sinS a. 118. a..

6cosT+1

2 Y8. (8 1+81) 119• ---...~;:;;===;::;;--

V4S!-SI

120. 4 cos]-V(Rt-R1) (R. Sinll.~+Rlcost]) .

{

sinl!. COSI a.+1'

12t. 1~. 122. ~I + 2 IX 2 •

al cost - 2

123. Val+bl-ab, Val+bl+ab. t25. 15°, 75°.

R Vi ../- ~r-

126. -8-. 127. 2 , 6. 128. f 2.

129. !(2 Y3+3). 130. 2RI. sinS a sin ~

3 SiD «(I+1') •

13t. 3 va ~J3 -1). 132. 1.1 133. If 4/4 <

R < a/2 t there is only one solution: al / (t 6R).

If 0 < R ~ 4/4 or R ~ 2, we have two solutions:

a'/(16 R) and a'/(8 R).

n RI_rl

134. T and arccos RI+rl • 135. 30°.

136. aY7/4. 137. R(3-2V2)/3.

.. lOt-cos ~ 39 ab tan a.

138. 4 V a-cos ~. 1 · Val tan' cz+(a-bl) •

(In the triangle ONP, KP and NM are altitudes,

therefore OA is an altitude.)

140. 2Rr/(R +r). 141. a/2.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-140921124347-phpapp02/75/SHARIGUIN_problems_in_plane_geometry_-167-2048.jpg)

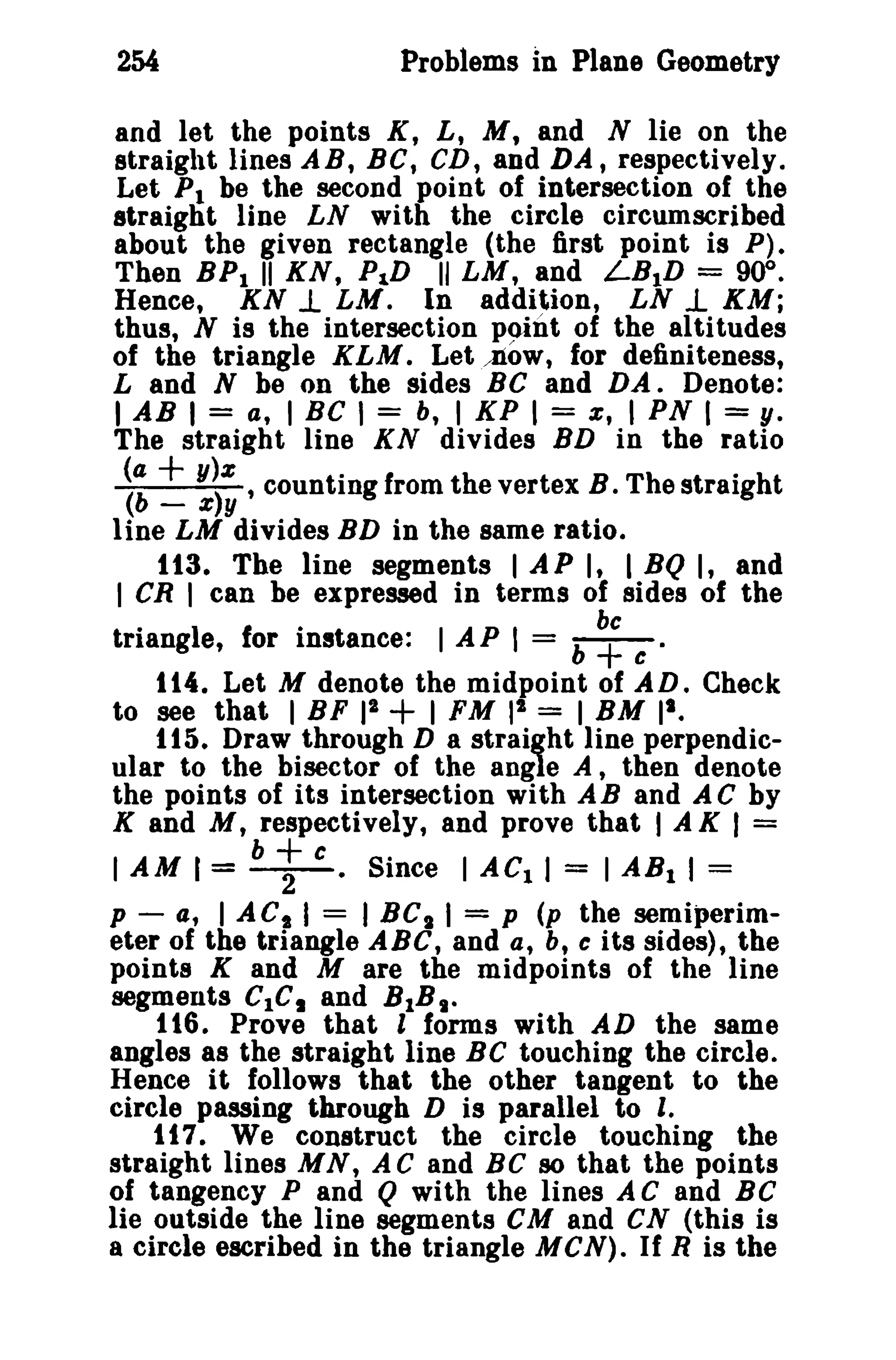

![Answers, Hints, Solutions 165

143. The error does not exceed 0.00005 of the

radius of the circle.

t". 113-56 V3. t45. 7.5. t46. 3 1~

11.7 231 11.Q ]/3+ Vt5 11.9 2 V3

•. 3' ~. 2 • ~. 3 •

~r- 16 (.,-) V5 150. 4 t' 3. 151. 9 4- v 7. 152. T'

t53. 2r2 sin 2 a. sin 2a.. tM. 2 -}.

5 t (3 V3) 155. 12n+Tarccos 1t-T ·

156. Vi'2(2- va). 157. ar/(a+2r).

1t 158. If a < '3' then the problem has two

solutions: R2 sin a. ( 1 ± sin ~ ) ; if ~ ~ a.< 31,

the only one: R2 sin a. ( 1+sin ~ ) •

159. From ; (3 V2-4) to ;. 160. From

I al-bl I 2abc

a'+bl to 1. 161. ab+bc+ca'

(Through an arbitrary point inside the triangle,

we draw three straight lines parallel to its sides.

Let the first line cut off the triangle which is sim ilar

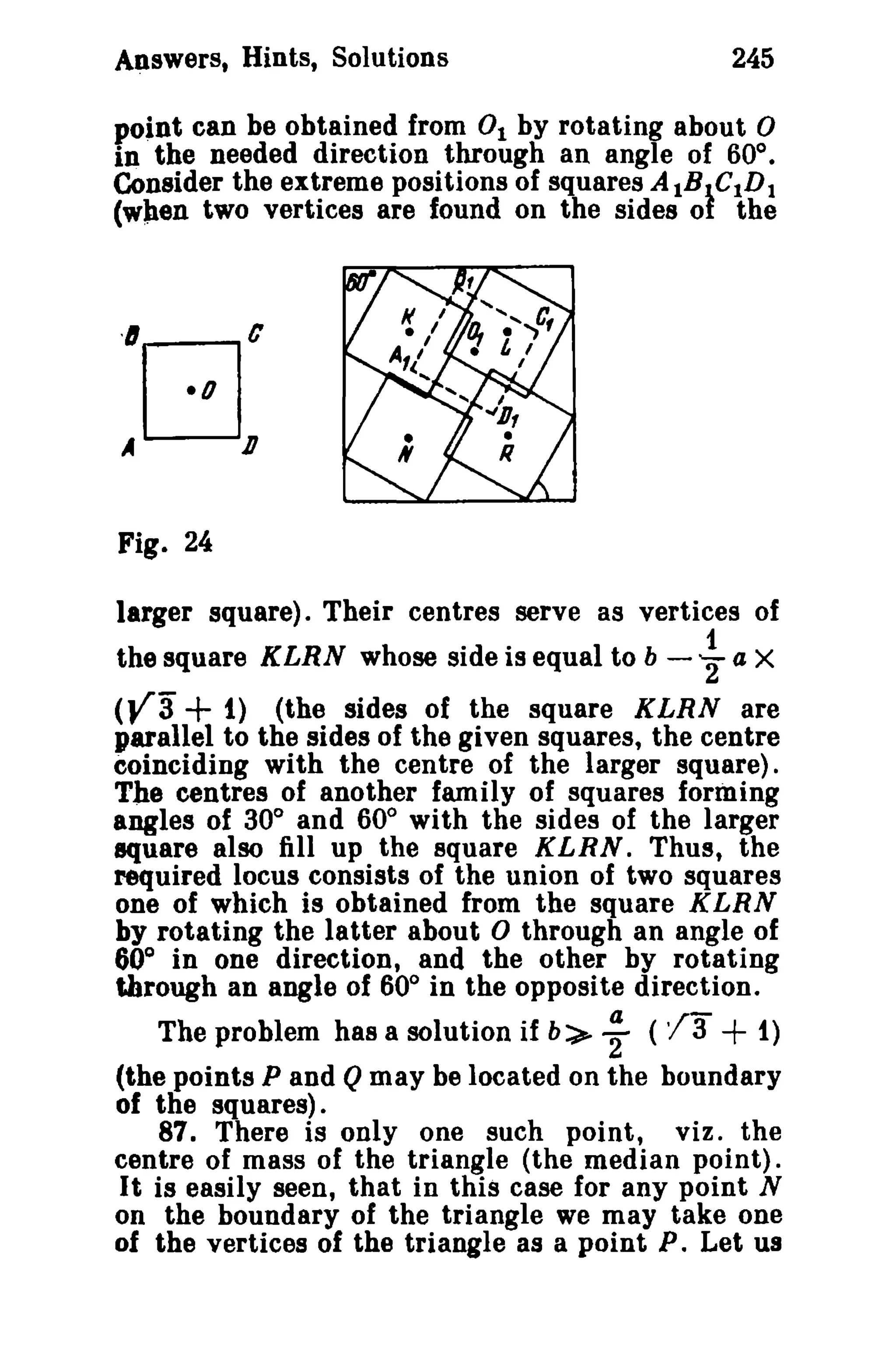

to the original one with the ratio of similitude

equal to A, the second line, with the ratio equal to

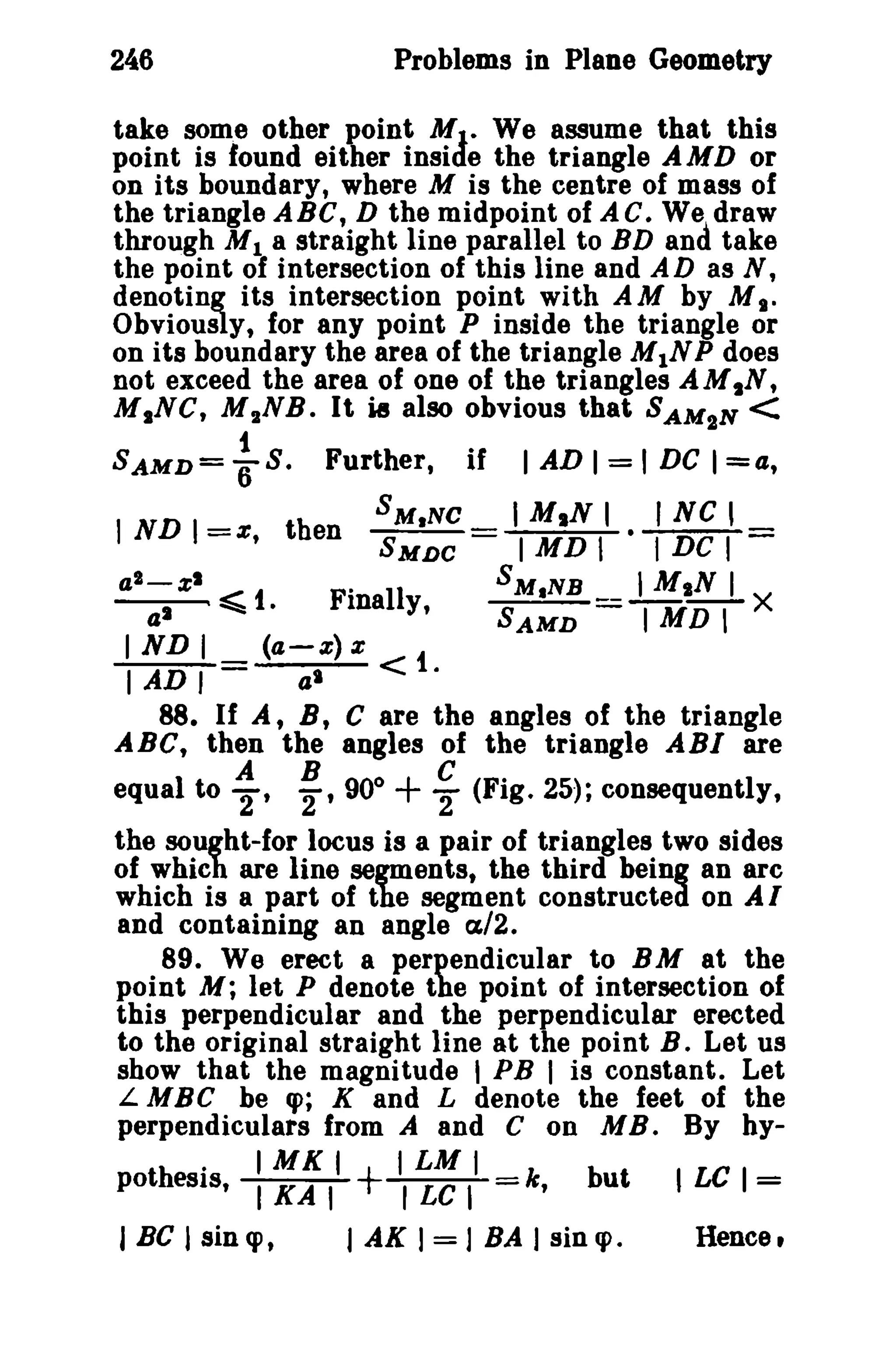

fit and the third-with y. Prove that A+ JJ. +

y = 2.)

Rr

f62. .R+r •

163: Take on the line BA a point Al such that

I AlB I = I Ale I. The points A, A. D and C](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-140921124347-phpapp02/75/SHARIGUIN_problems_in_plane_geometry_-168-2048.jpg)

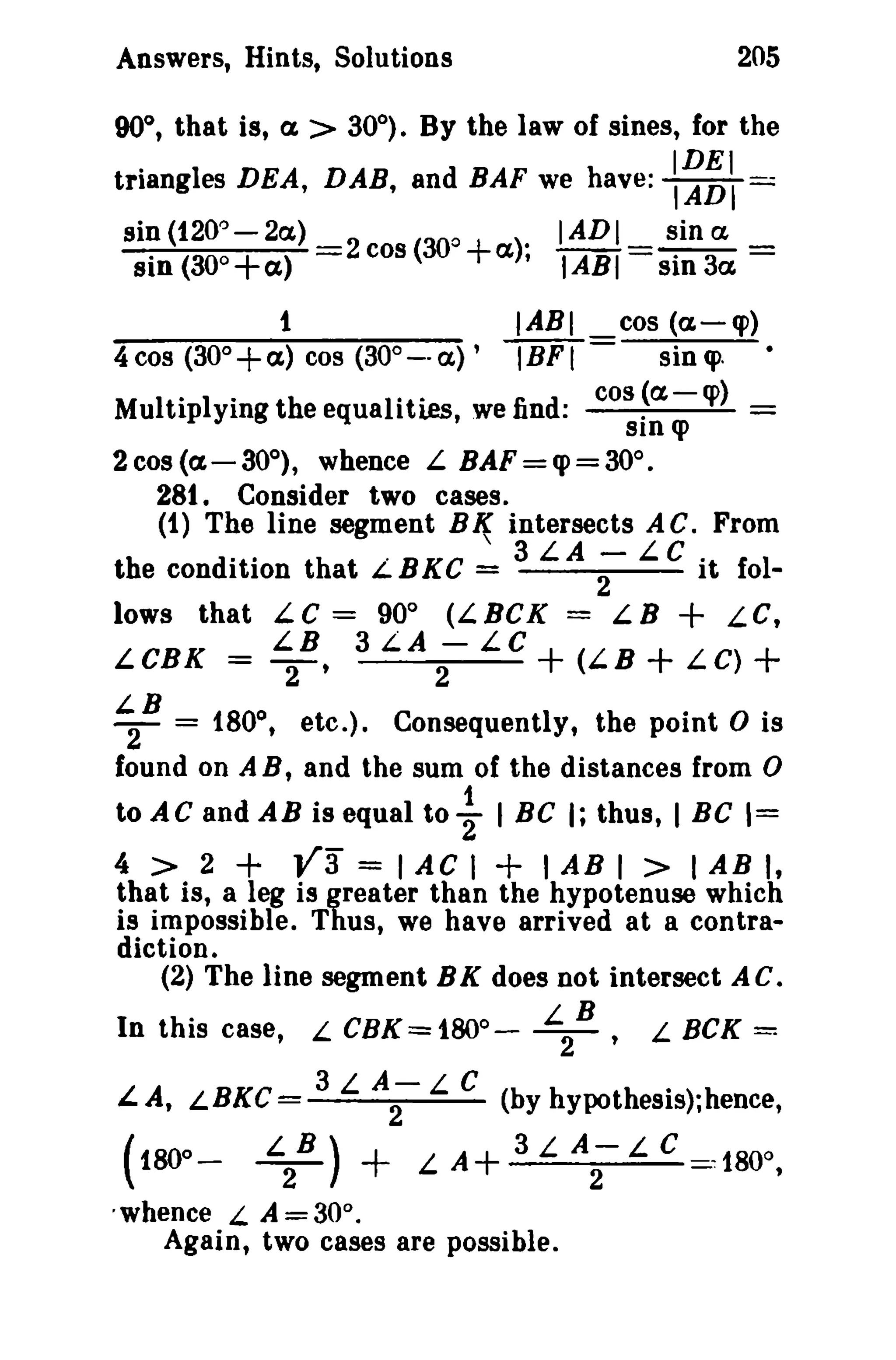

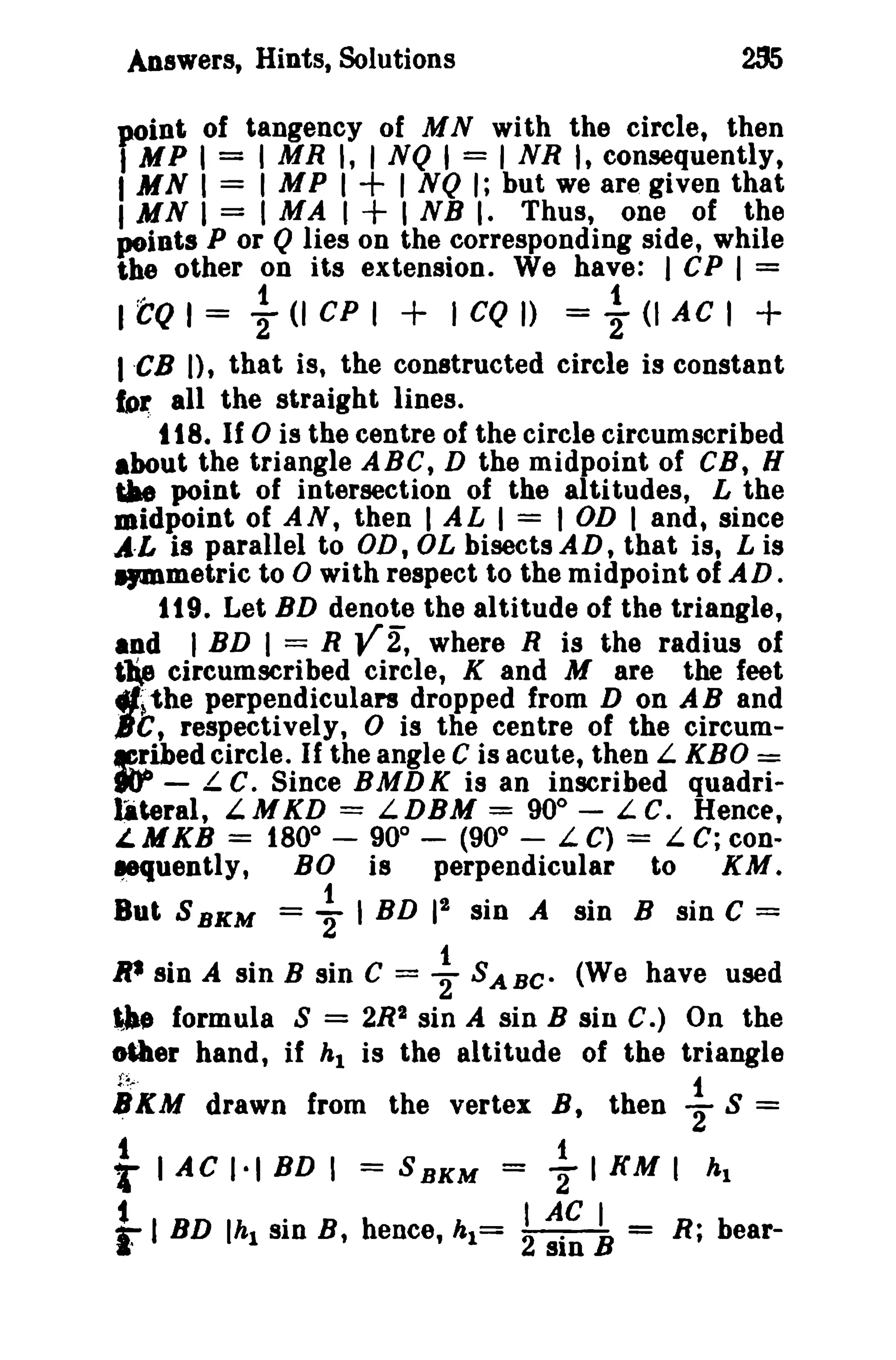

![Answers, Hints, Solutions {G9

a + e be . -2- , a + e (a, b, and c the sides of ~ABC),

which is similar to the triangle ABC. Consequently,

-b+a : a + c be a = -2- b = -+:c, so a + e == a cae

bV'2. Since a =1= c, at least one of the two

inequalities b =1= a, b =1= c is true. Let b -=1= c, then

b + e = ,. V2, b = a, and we get a triangle

with sides a, 4, a (V2 - I), possessing this

property. Thus, there are two classes of triangles

satisfying the conditions of the problem: regular

triangles and triangles similar to that with sides

i, 1, V2 - t.

188. If a is the angle between the sides a and b,

then we have: a + b sin a ~ b+a. sin a, (a-b)X

(sin a; - 1) :>- 1, sin a> t. Hence, ex, = 90°.

Amwer: Va2 + v.

189. Prove that of all the quadrilaterals circumscribed

about the given circle, square has the

least area. (For instance, we may take advantage

of the inequality tan ex, + tan p:>- 2 tan (ex, + P)/2]

where a; and pare acute angles.) On the other hand,

t

SABCD ~ 2(1 MA 1·1 MB I + 1MB 1·1 Me I +

I MC I" MD 1+' MD r I MA I) :s;;~ (IMAI2+

I MB II) +i- (I MB 11+ I MC 11)+}<lMCII+

I MD II) + ~ <I MDI2 + I MA 12) = 1. Consequently,

A CBD is a square whose area is 1.

tOO. Let us denote: I BM I = z, I DM I = y,

I AM 1= t L.AMB = cp. Suppose that M lies

on the line segment BD. Writing the law of cosines

for the triangles AMB and AMD and eliminating

cos q>, we get: I' (z + y) + zy (z + U) = a2y +

cJIz. Analogously, we get the relationship zt (z+y)+](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-140921124347-phpapp02/75/SHARIGUIN_problems_in_plane_geometry_-172-2048.jpg)

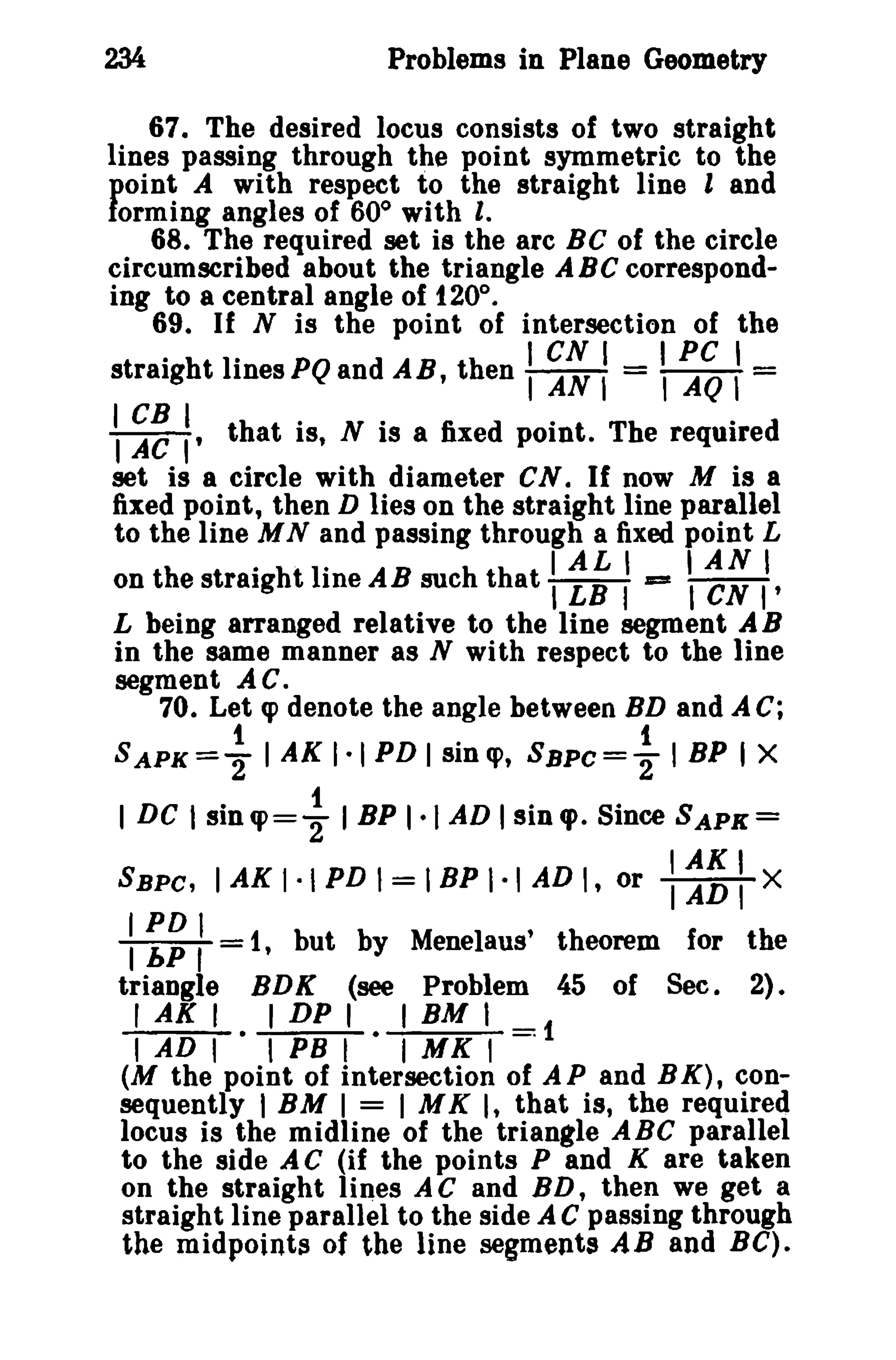

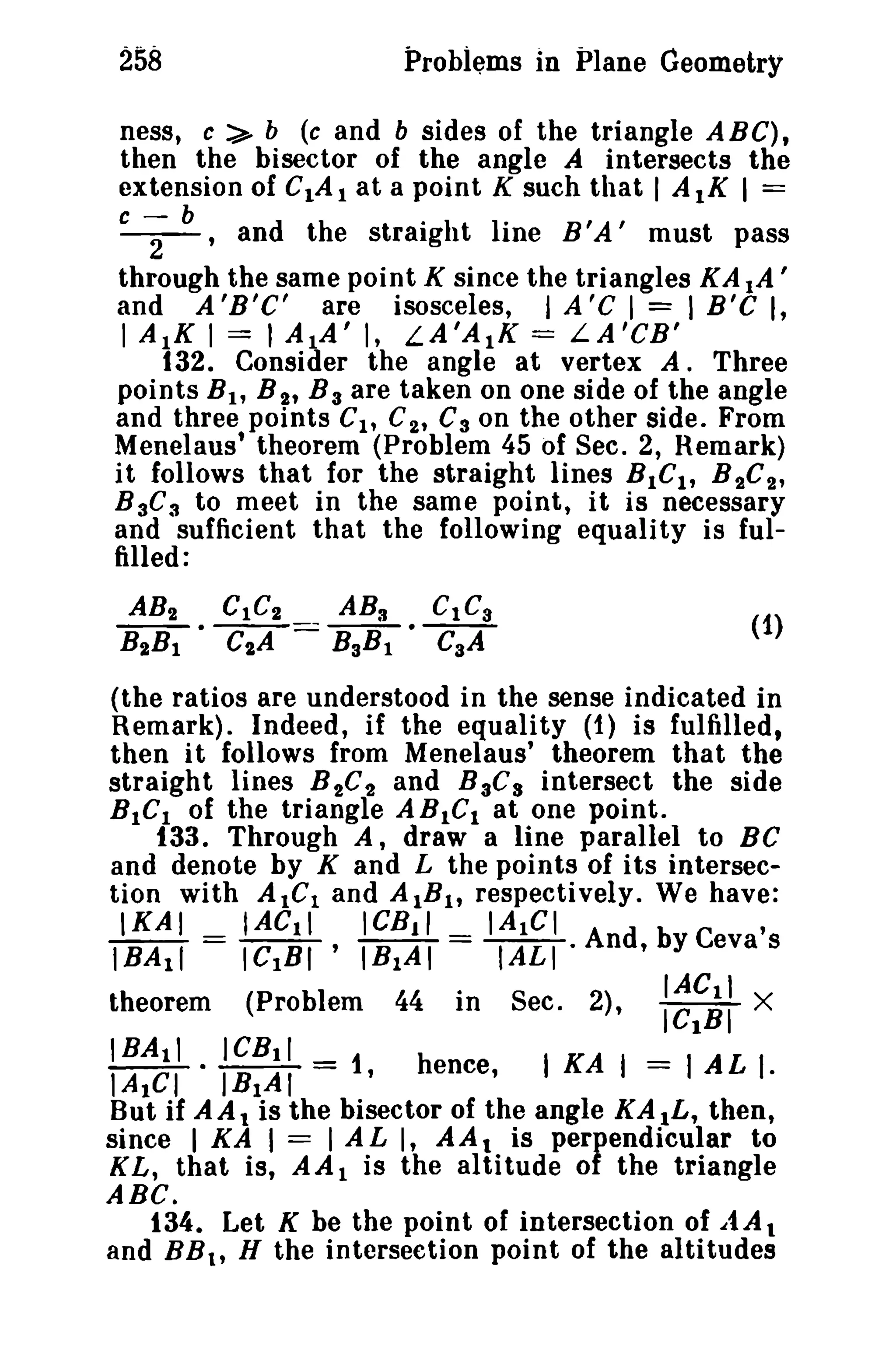

![Answers, Hints, Solutions 175

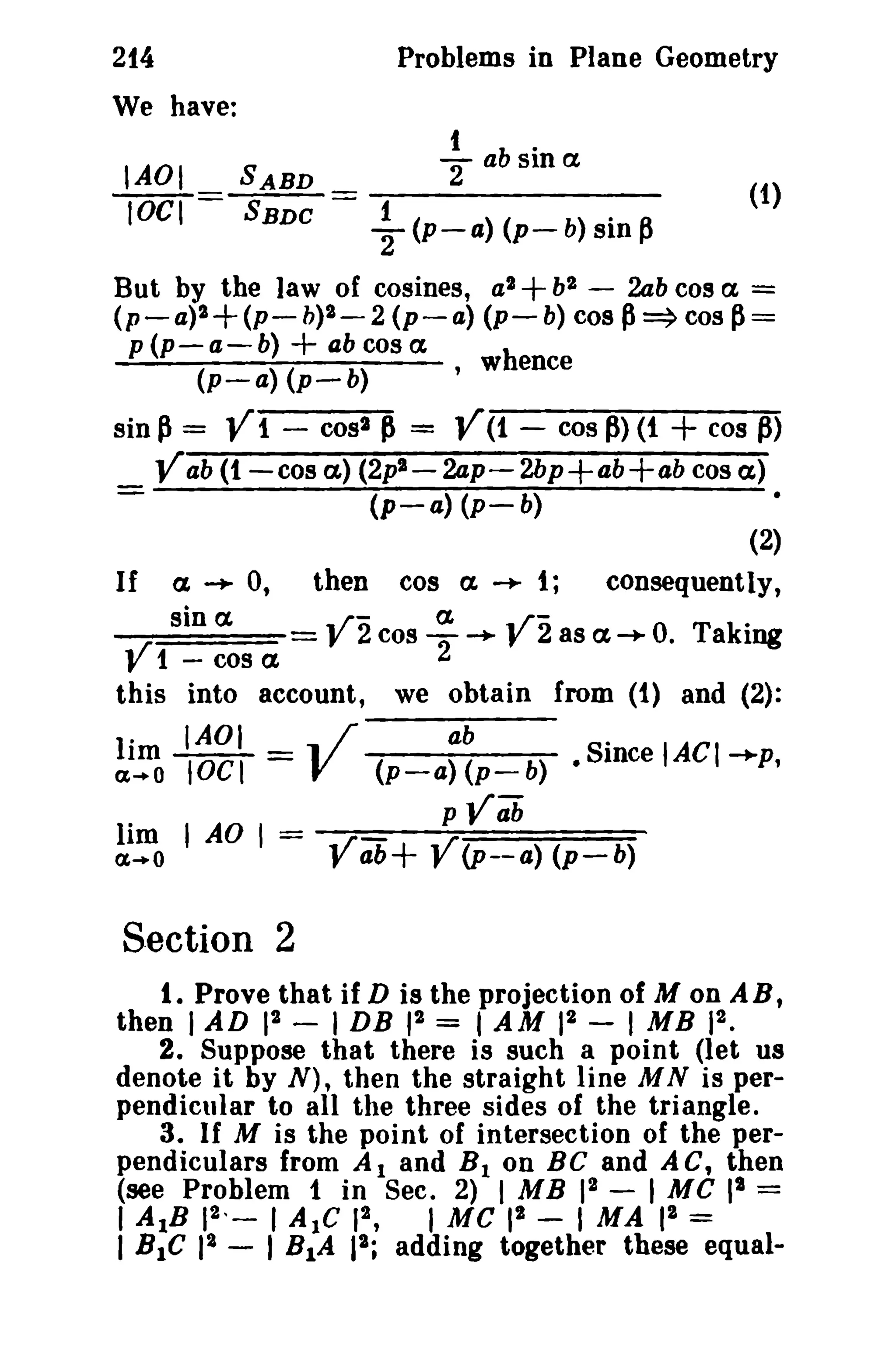

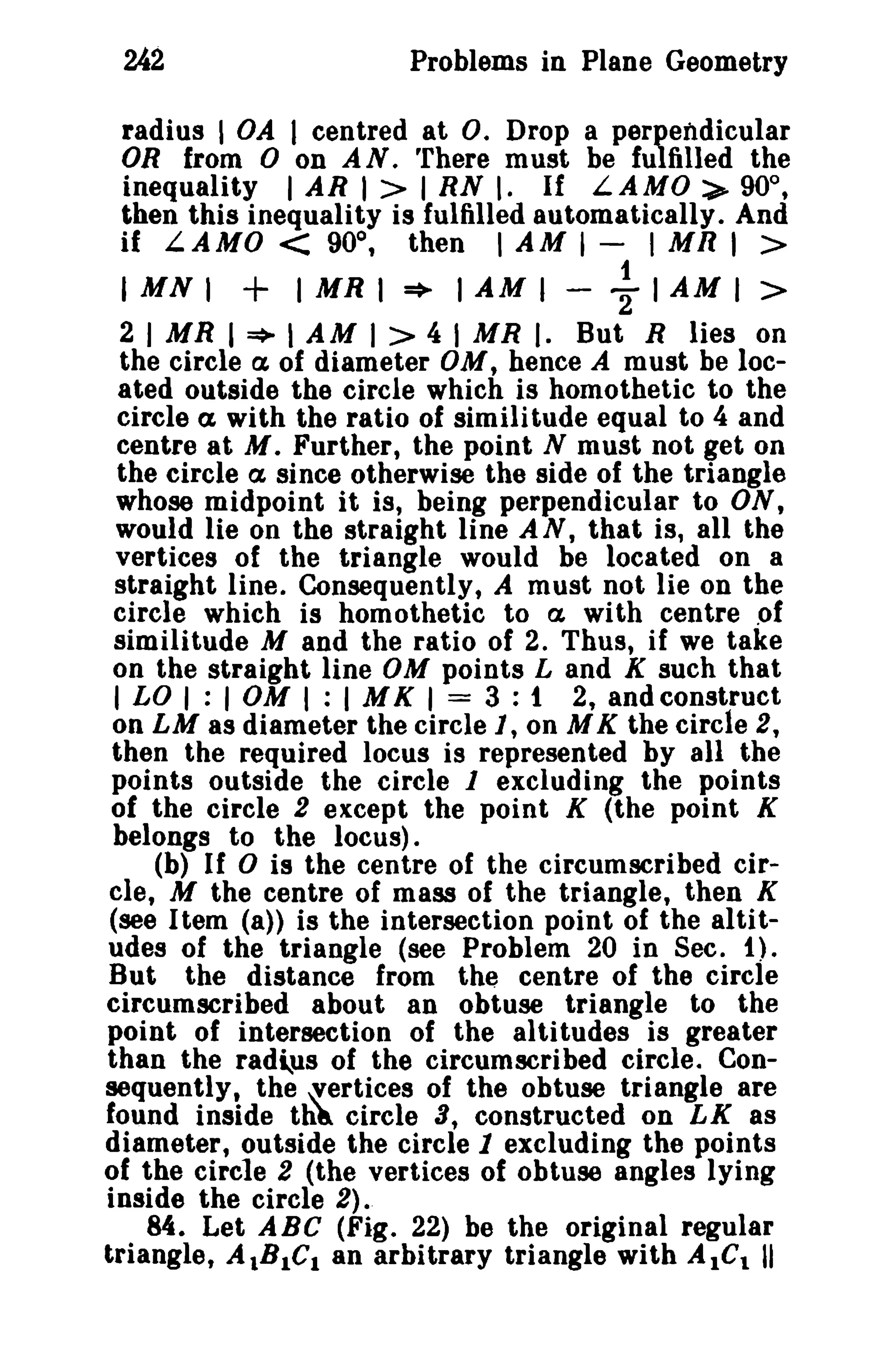

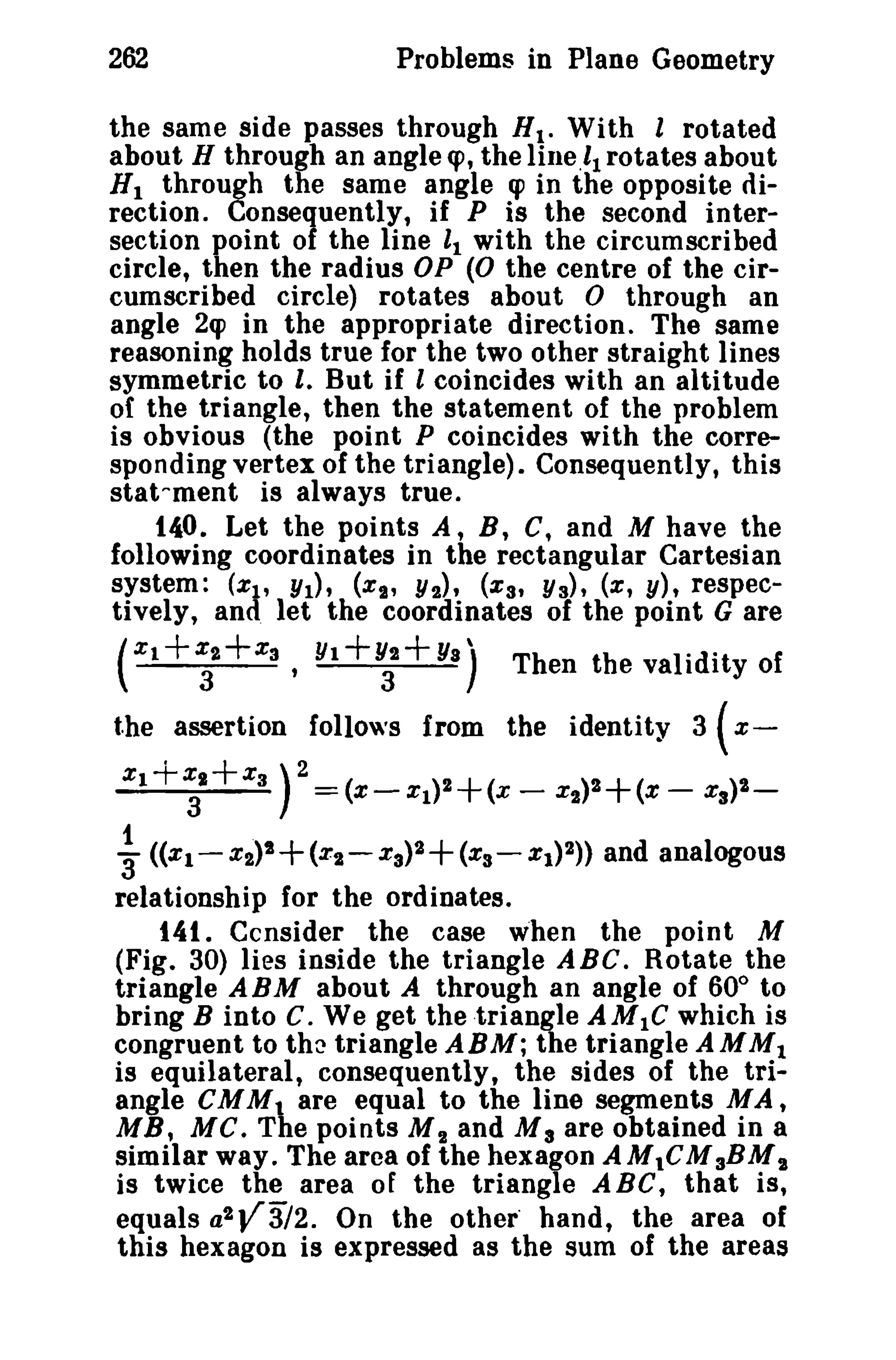

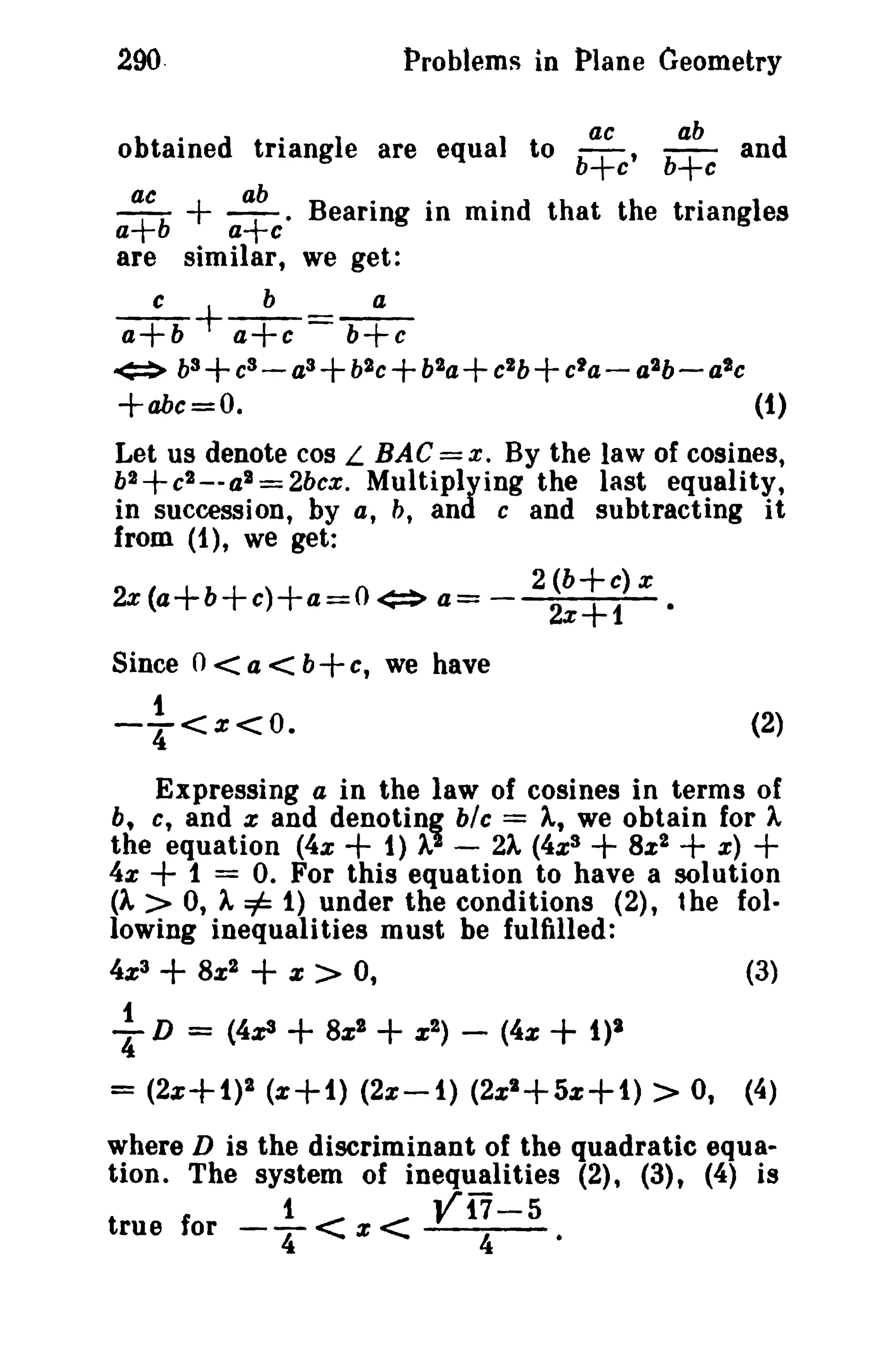

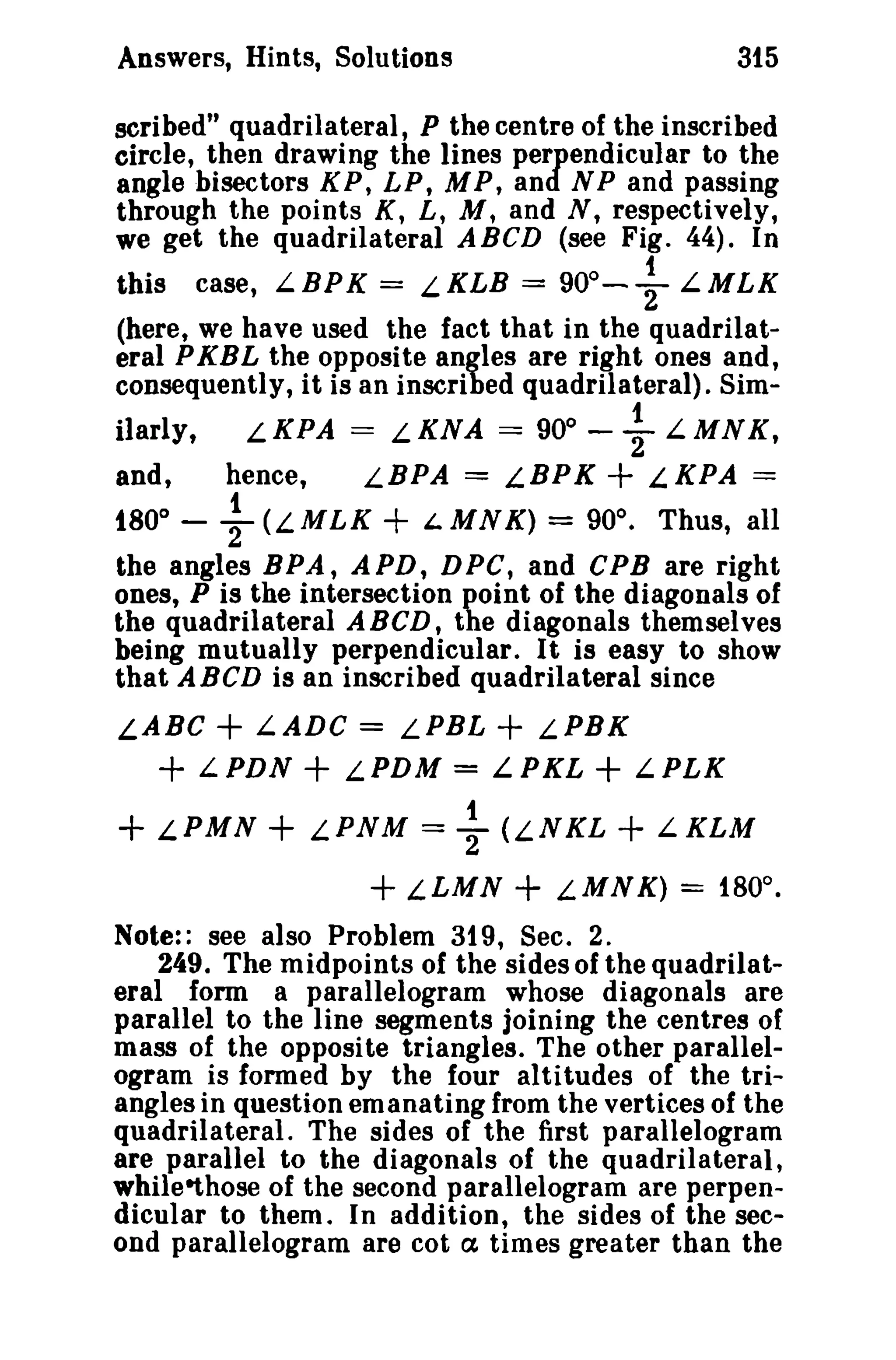

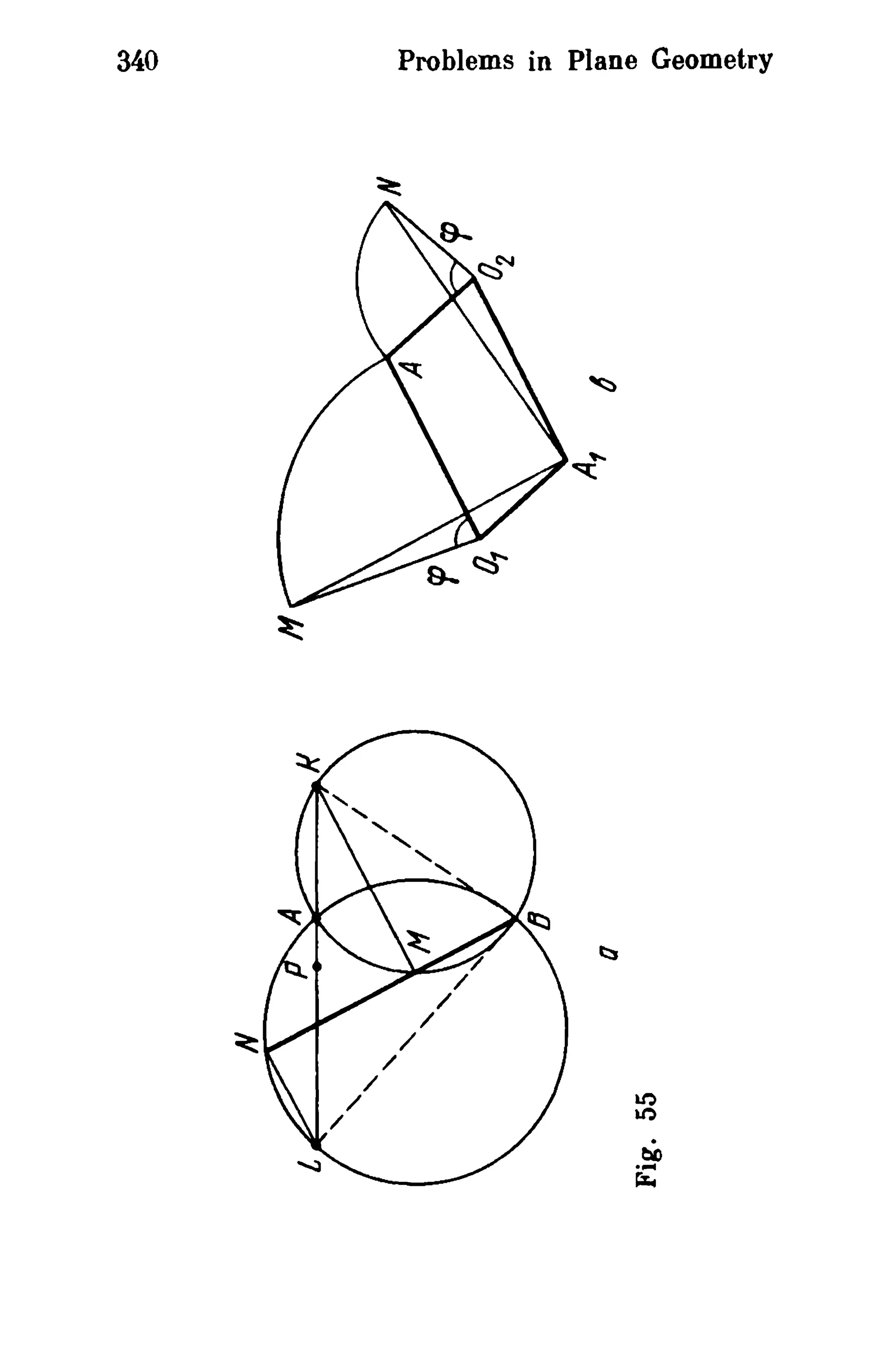

203. Let ABC denote the given triangle, 0, X,

H the centres of the circumscribed and inscribed

circles, and the intersection point of the altitudes

of the triangle ABC, respectively. Let us take

advantage of the following fact: in an .arbitrary

triangle the bisector of any of its angles makes

equal angles both with the radius of the circumscribed

circle and with the altitude emanating

from the same vertex (the proof is left to the reader).

Since the circle passing through 0, K, and H contains

at least one vertex of the triangle ABC (say,

the vertex A), it follows that 1OK 1= I KH I.

The point K is situated inside at least one of the

triangles OBB and OCH. Let it be the triangle

OBH. The angle B cannot be obtuse. In the triangles

OBK and HBK, we have: 1 OK I = I HK I,

KB is a common side, L DBK = L HB K. Hence,

6.0BK = b.HBK, since otherwise LBOK +

LBNK = 1800 which is impossible (K is inside

the triangle OBH). Consequently.] BH 1=1 BO 1=

R. The distance from 0 to AC equals 0.5 IBB 1=

O.5R (Problem 20 of Sec. 1), that is, LB = 600

(LB is acute), I AC 1= R V3. If now AI, B1,

and Clare the points of tangency of the sides BC,

CA, and AB to the inscribed circle, respectively,

'then 1BAI I = I BCI 1= r va, I C~l 1+IAC11=

I CBtl + t RtA I = lAC 1= R V3. The perimeter

of the ttiangle is equal to 2 va (R + r). It

is now easy to find i ts area.

Answer: va (R + r) r,

204. Let P be the projection of M on AB,

I API = a + e, Then I PB I = a - z, J M P I =

aV2

1/=Val-zl , IANI=(a+z) V .INBI=

a 2+y

24-(a+z) a Vi a Vi (4-Z+1/ Vi)

a V2+y = a V2+y](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-140921124347-phpapp02/75/SHARIGUIN_problems_in_plane_geometry_-178-2048.jpg)

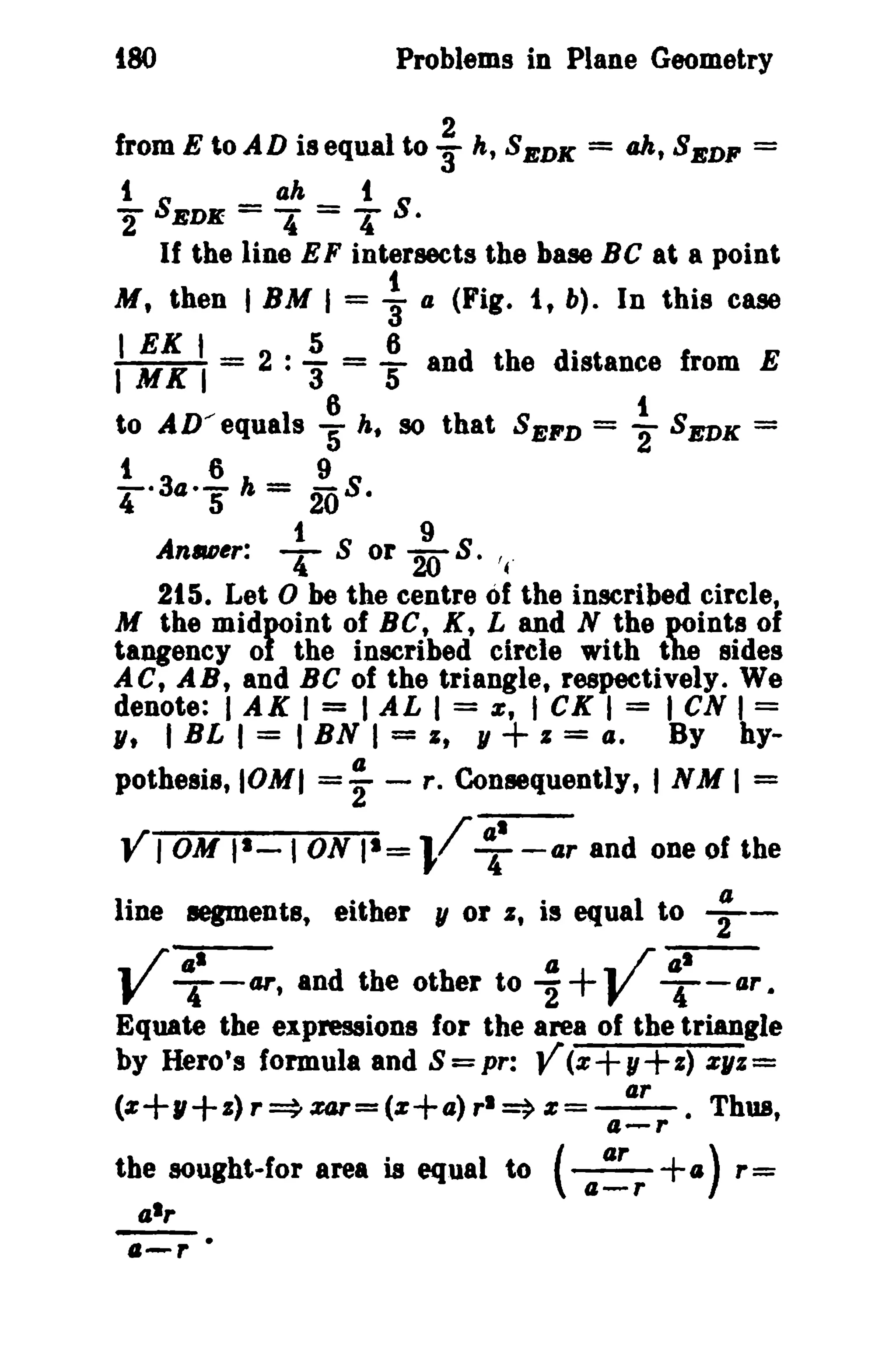

![178 Probiems in Plane Geometry

ION' % 83 8 183 I AM I . 8 1+ %

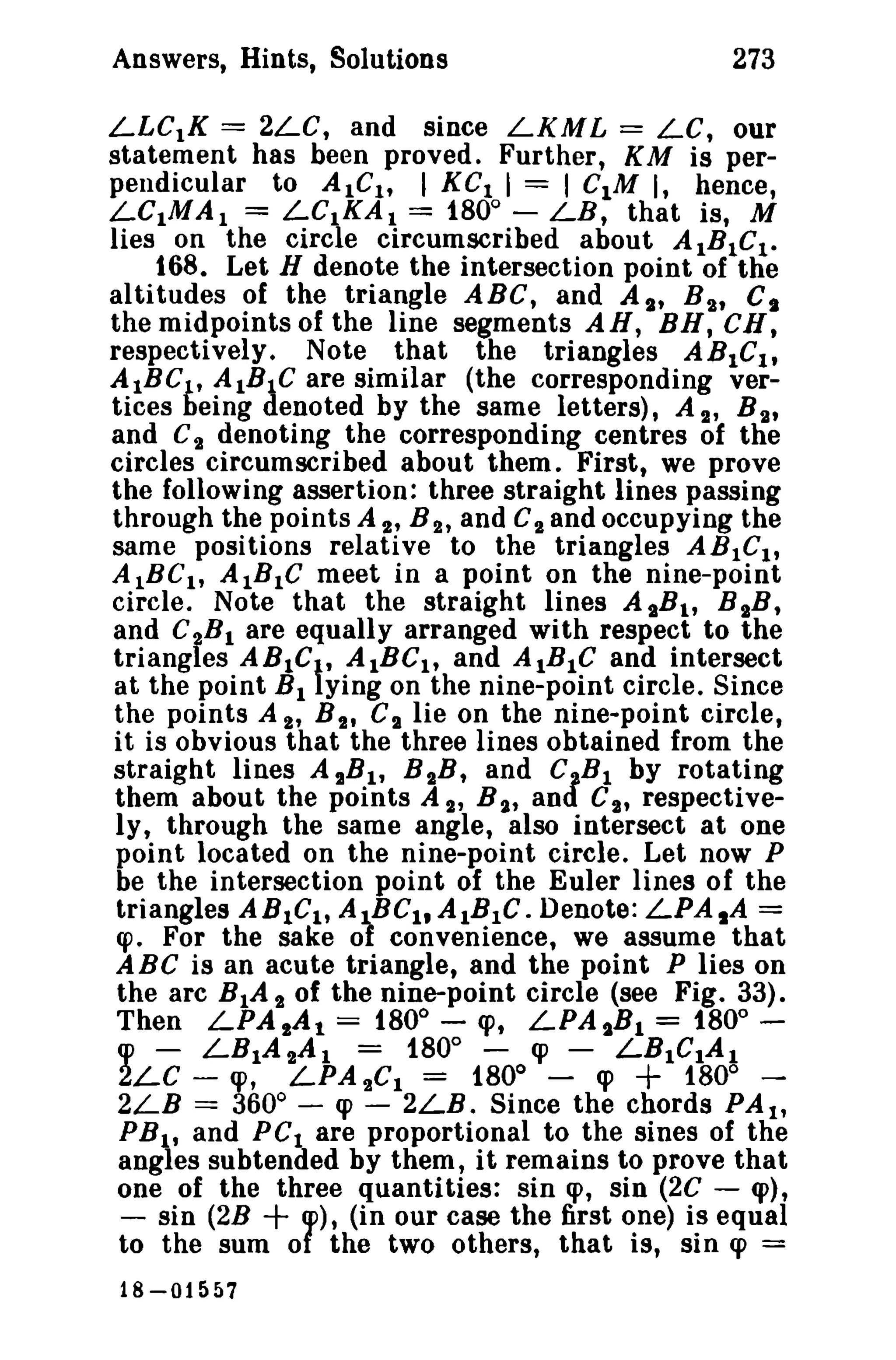

I VA I =S-;=::8;' %=-s;- , I MC , y =

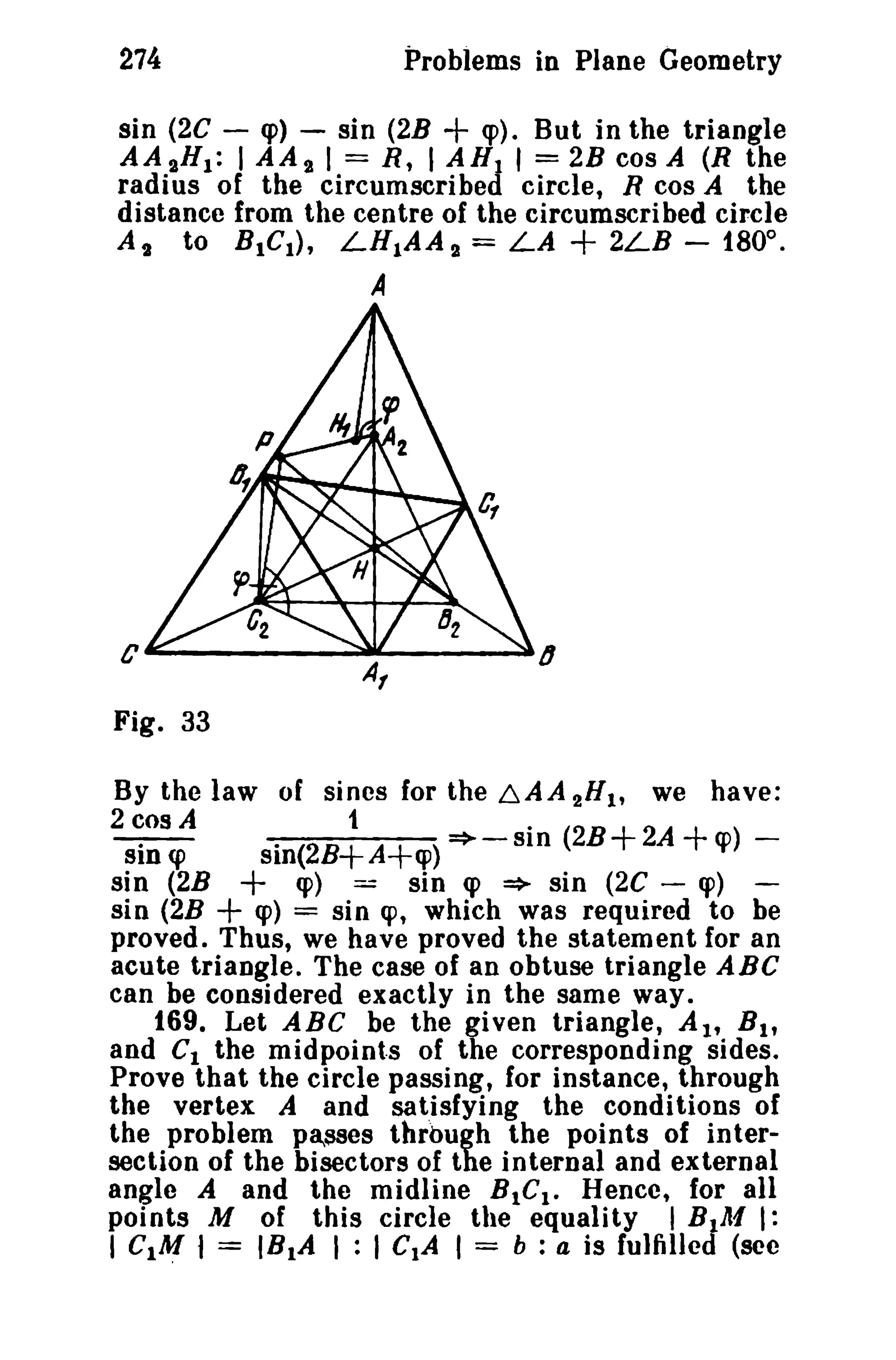

S8a1++z8+1y. The sought-for area is equaI t 0

8 183 (8 1+81) (83+82)

8 1 (81-8183)

21t . Let in the triangle ABC the angle C be

a right one, M the median point, 0 the centre

of the inscribed circle, r its radius, L B= a;

then I AB I = r (cot ~ +cot ( ~ -- ~ )) =

r vi . I cu I =-!. I AB I•

. a. ('" (1,) 3

sin T Sln T-T

ICOI=r IJt -2, 10M I=r, n L OeM = a. -4.

Writing the law of cosines for the triangle COM,

8 8%

we get 1=2+ ( --)2 ( y_) • where

9 2% - JI 2 3 2% - 2

(n) 4 V6-3 V2 z=cos T-a , whence %= 6 •

1t 4 V6-3 Y2

Answer: T ± arccos 6 •

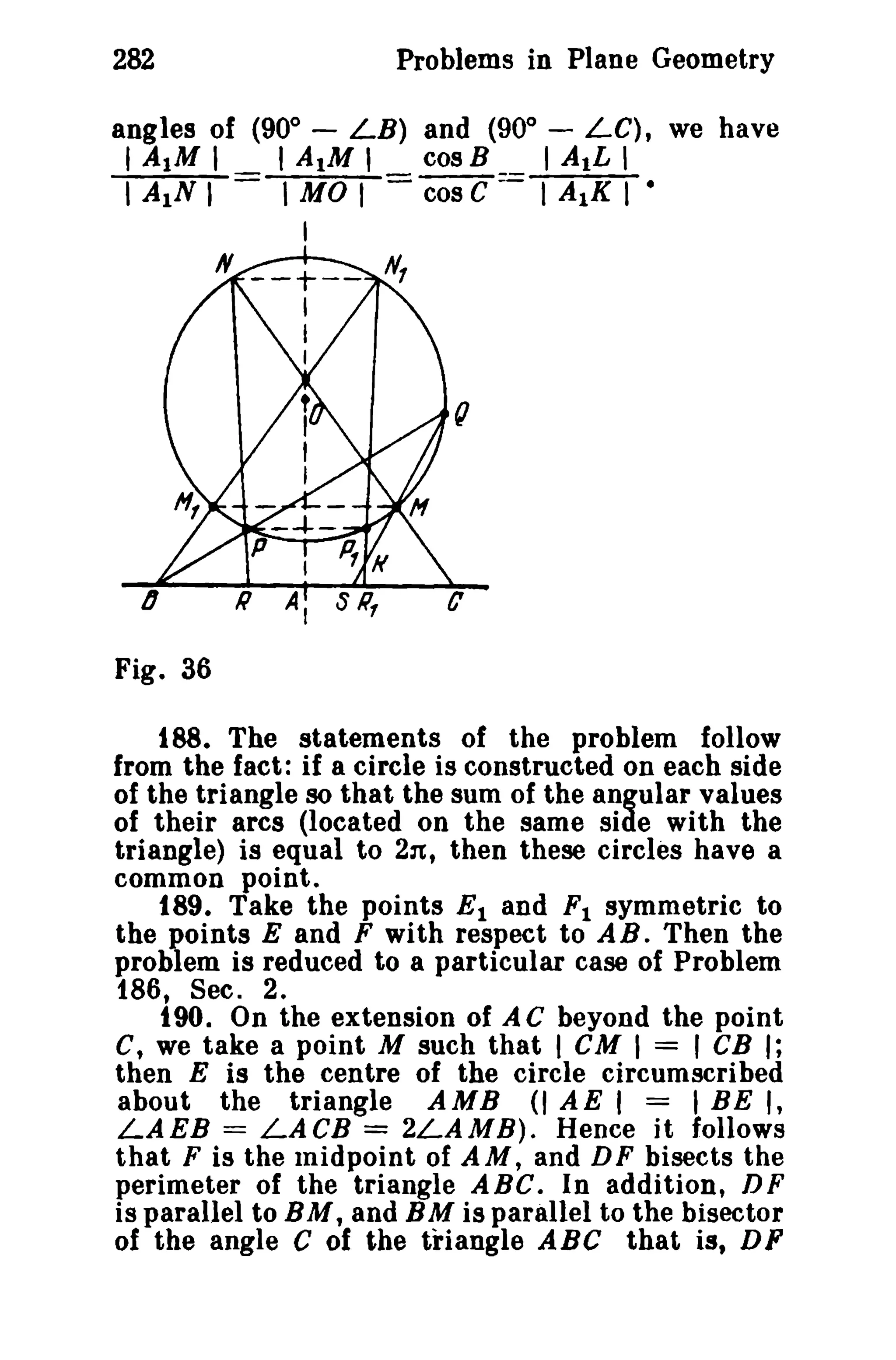

212. Let each segment of the median be equal

to 4. We denote by :z the smallest of the line

segments into which the side corresponding to the

median is divided by the point of tangency. Now,

the sides of the triangle can be expressed in terms

of a and a; The sides enclosing the median are

a y2" + z, 3a y2" + z, the third side is

2a y2" + 2%. Using the formula for the length of

a median (see Problem 1t, Sec. 1), we get 9a2 =

1 ~r- ~r- "4 [2 (4 y 2 + x)2 + 2 (3a r 2 + x)2 -

(2a Y2 + 2%)2], whence :z = a V2i4.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-140921124347-phpapp02/75/SHARIGUIN_problems_in_plane_geometry_-181-2048.jpg)

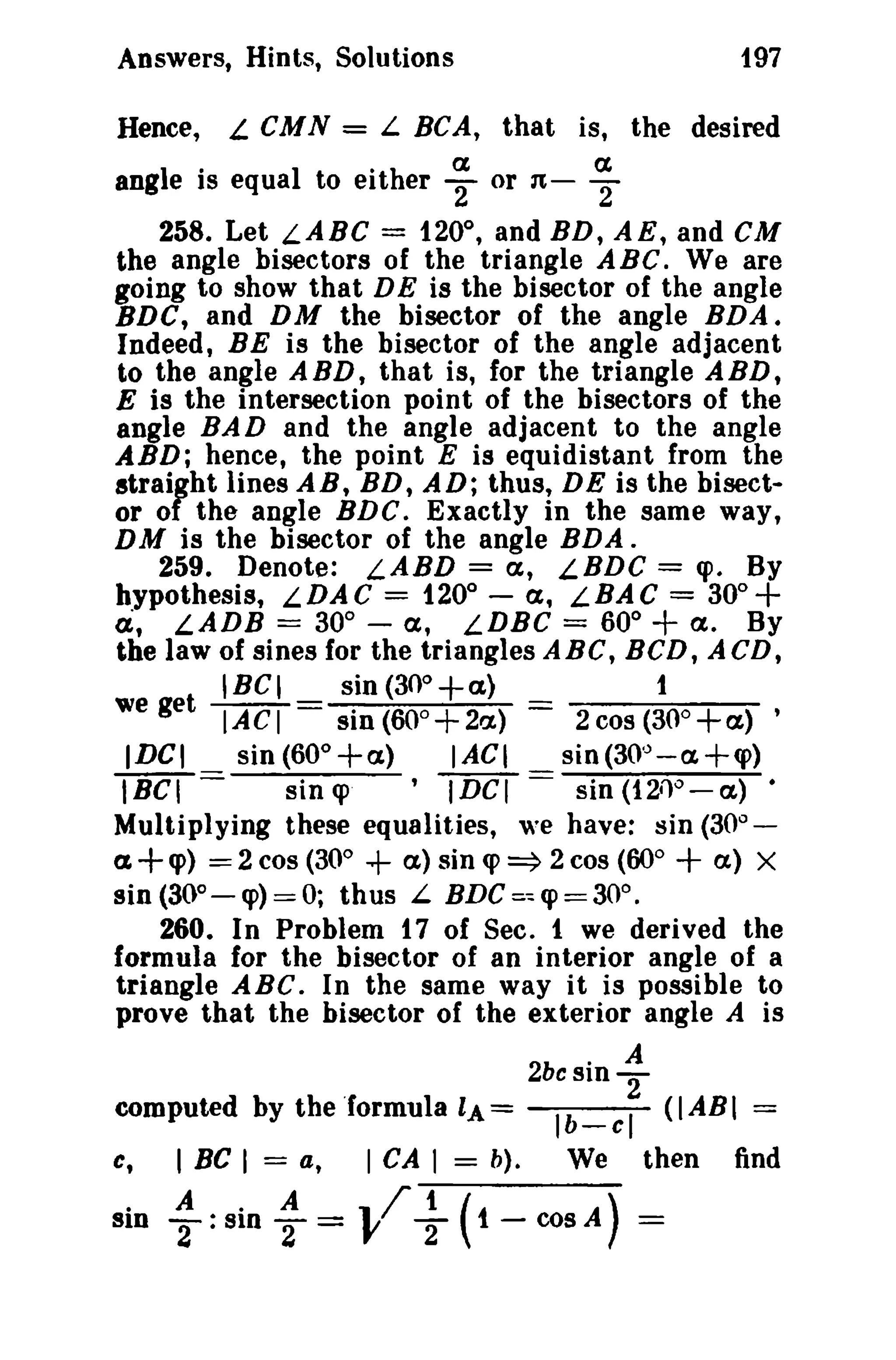

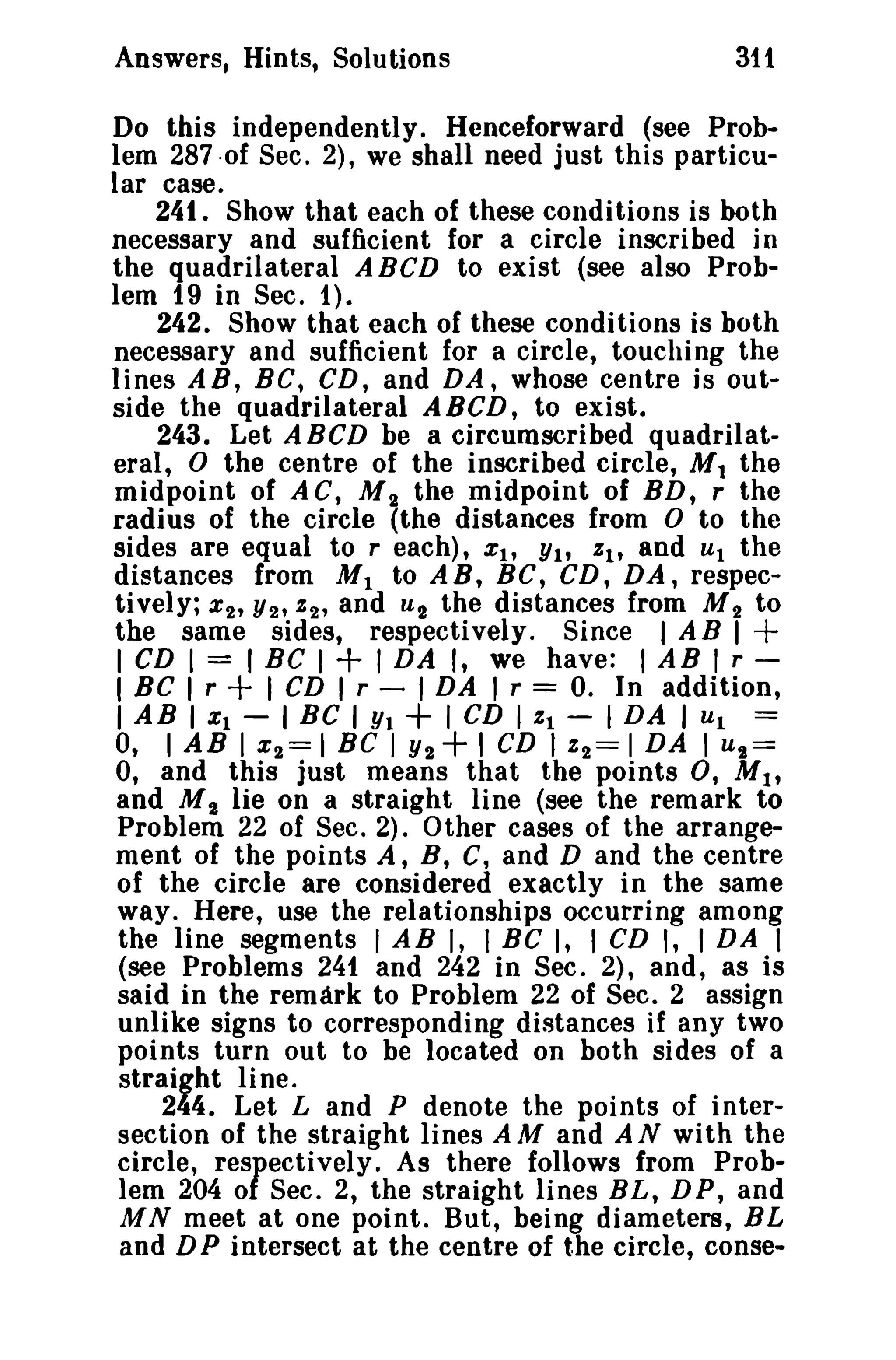

![196 Problems in Plane Geometry

LKMB = 180° - LKMC; if the point K lies

on the extension of NM, then LeOK = LCMK).

Thus, LOKC = LOMC = 90°.

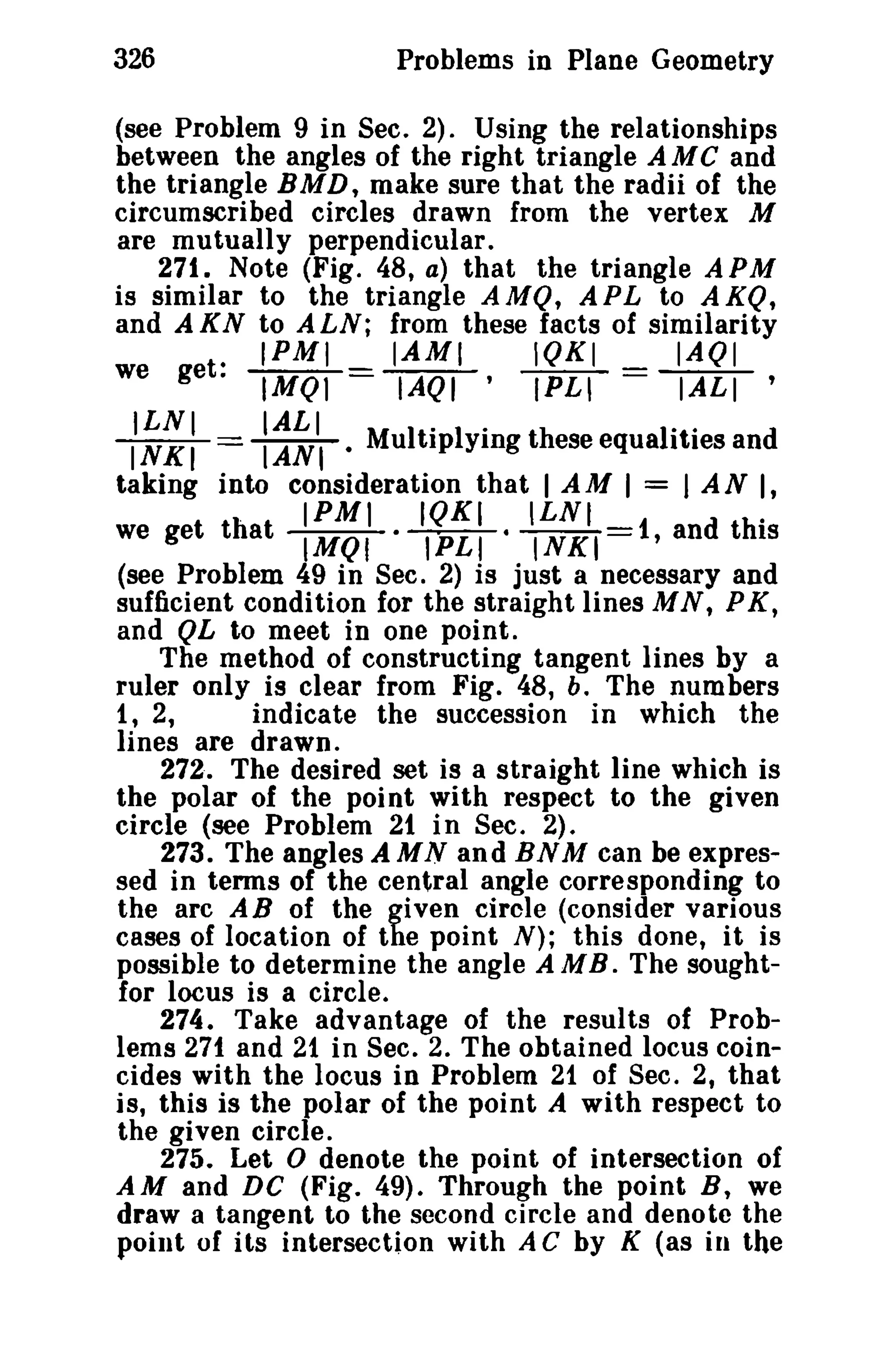

256. If P lies on the arc AR, Q on the arc AC,

then, denoting the angle PAB by (J), and the angle

QA C by '1', we get two relationships:

{

sin2 (C - cp) == sin q> sin (B + C - cp),

sin2 (B - 11') = sin", sin (B + C - 'l').

Writing out toe difference of these equalities and

transforming it, we get: sin (B + C - q> - '1') X

sin (B - C) + (cp - 'l')]=sin (B + C - cp-",)X

sin (cp - '1'), whence (since 0 < B + C - «p ;>

< n) B - C + cp - "I' = :t - (cp - '1') and we

get the answer.

n-a

Answer: -2-

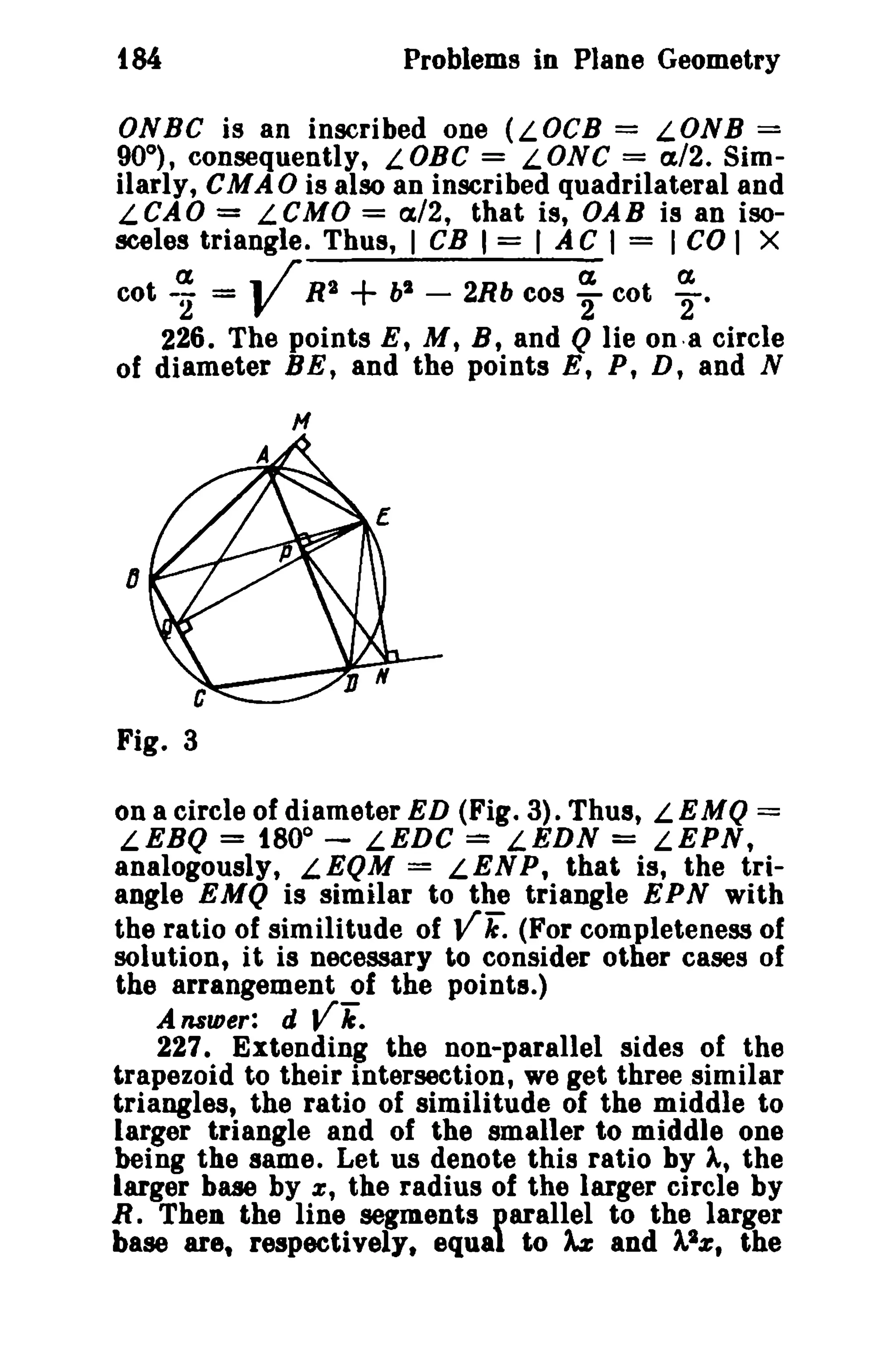

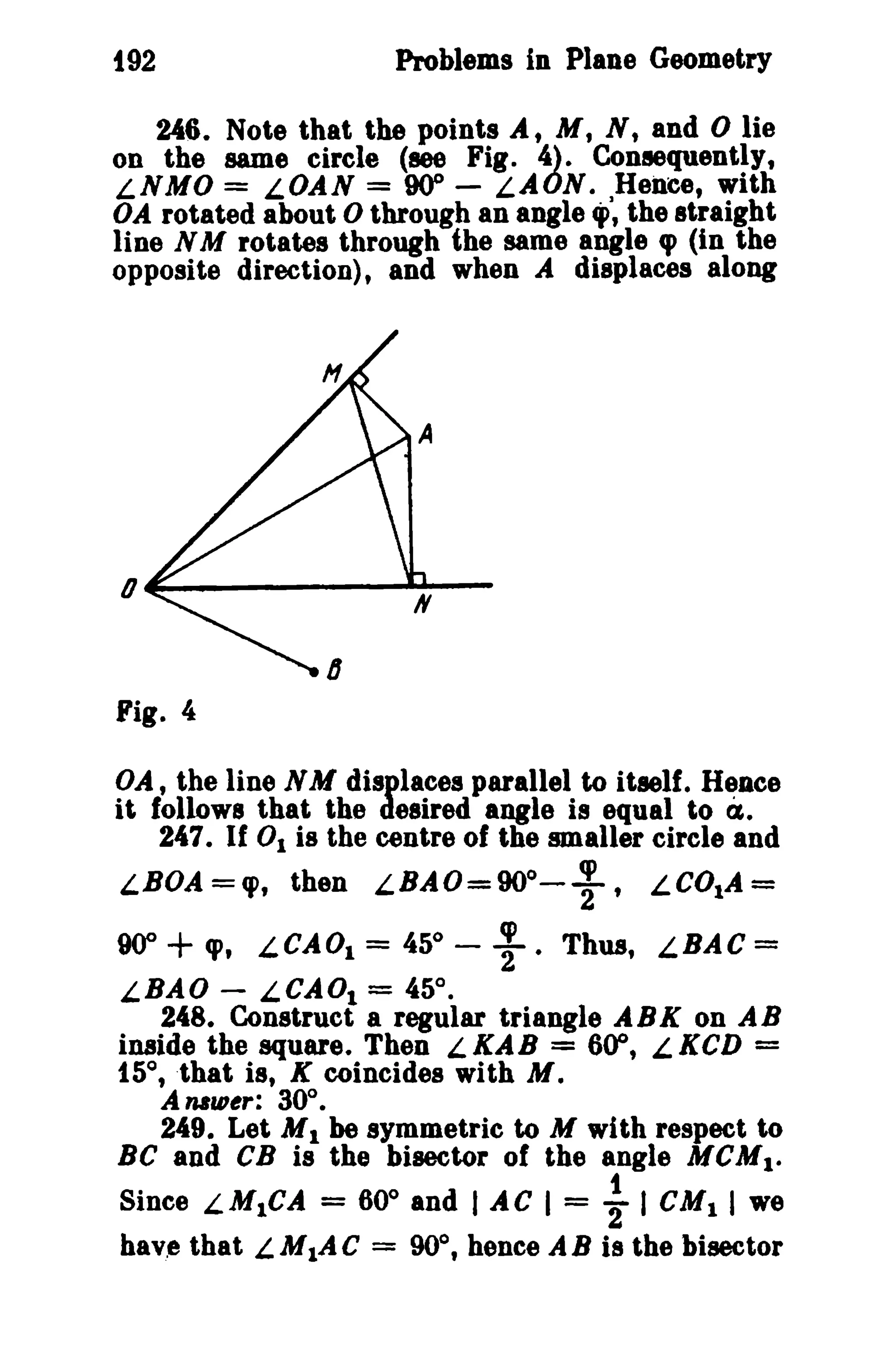

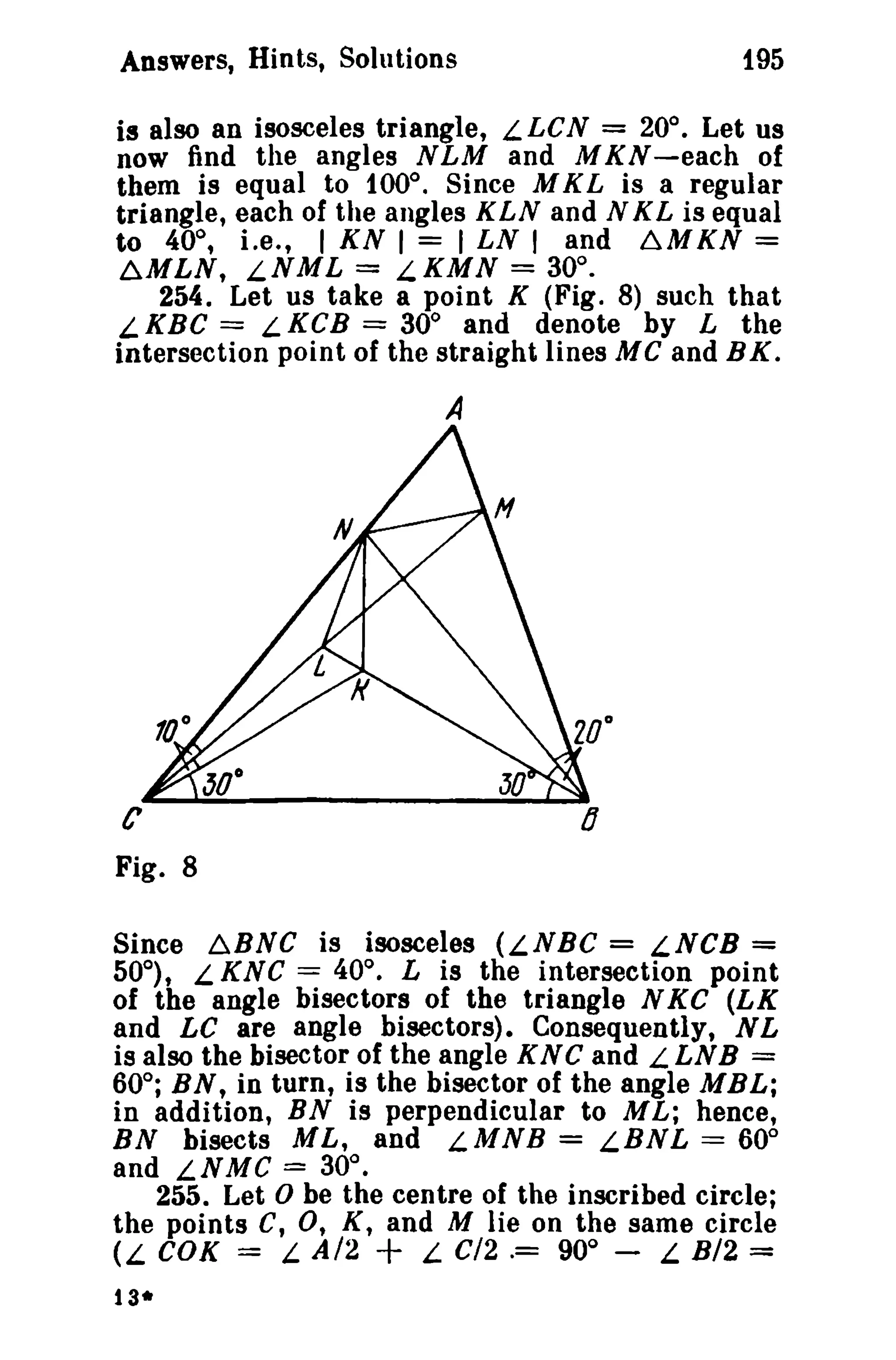

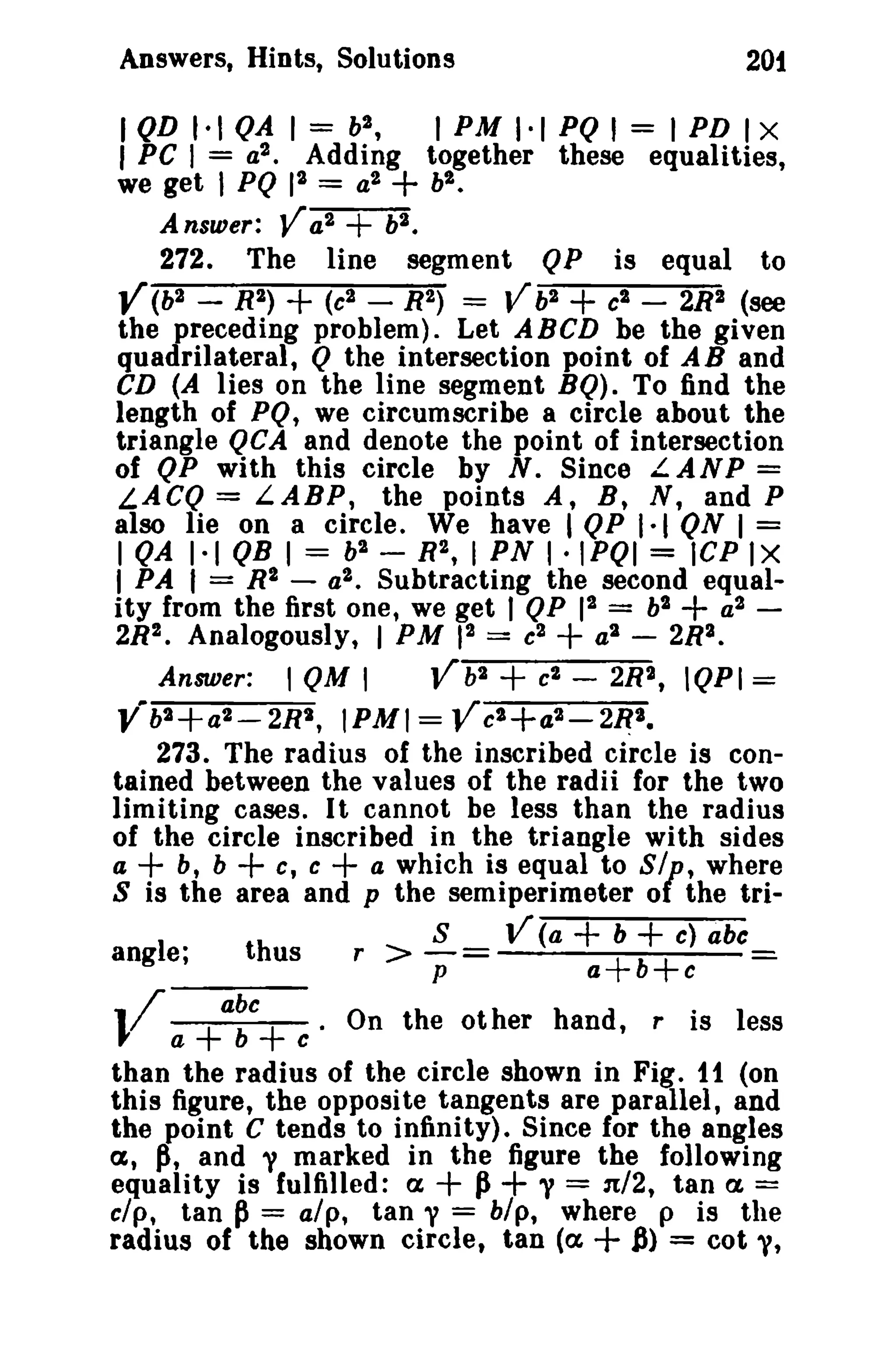

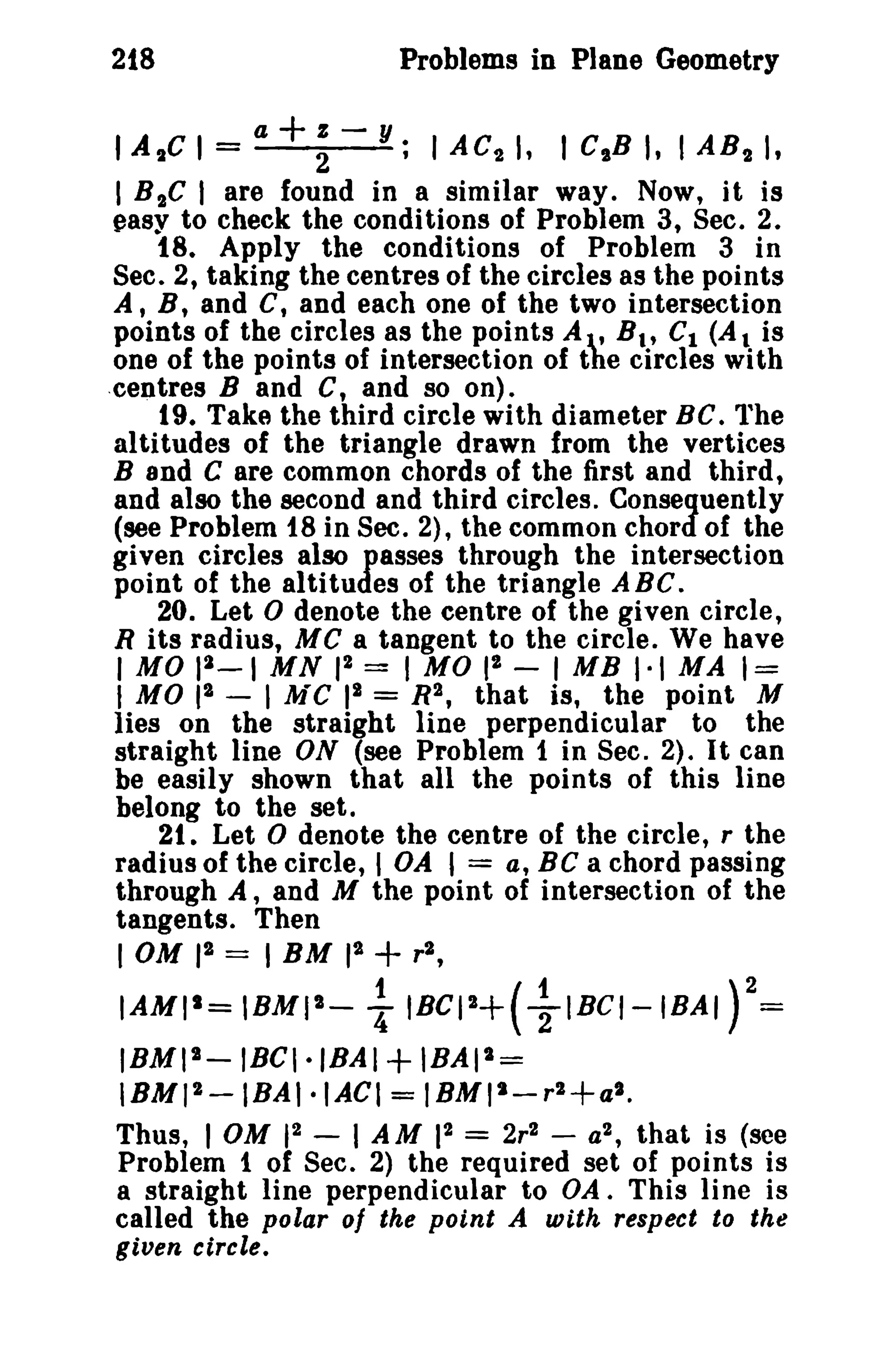

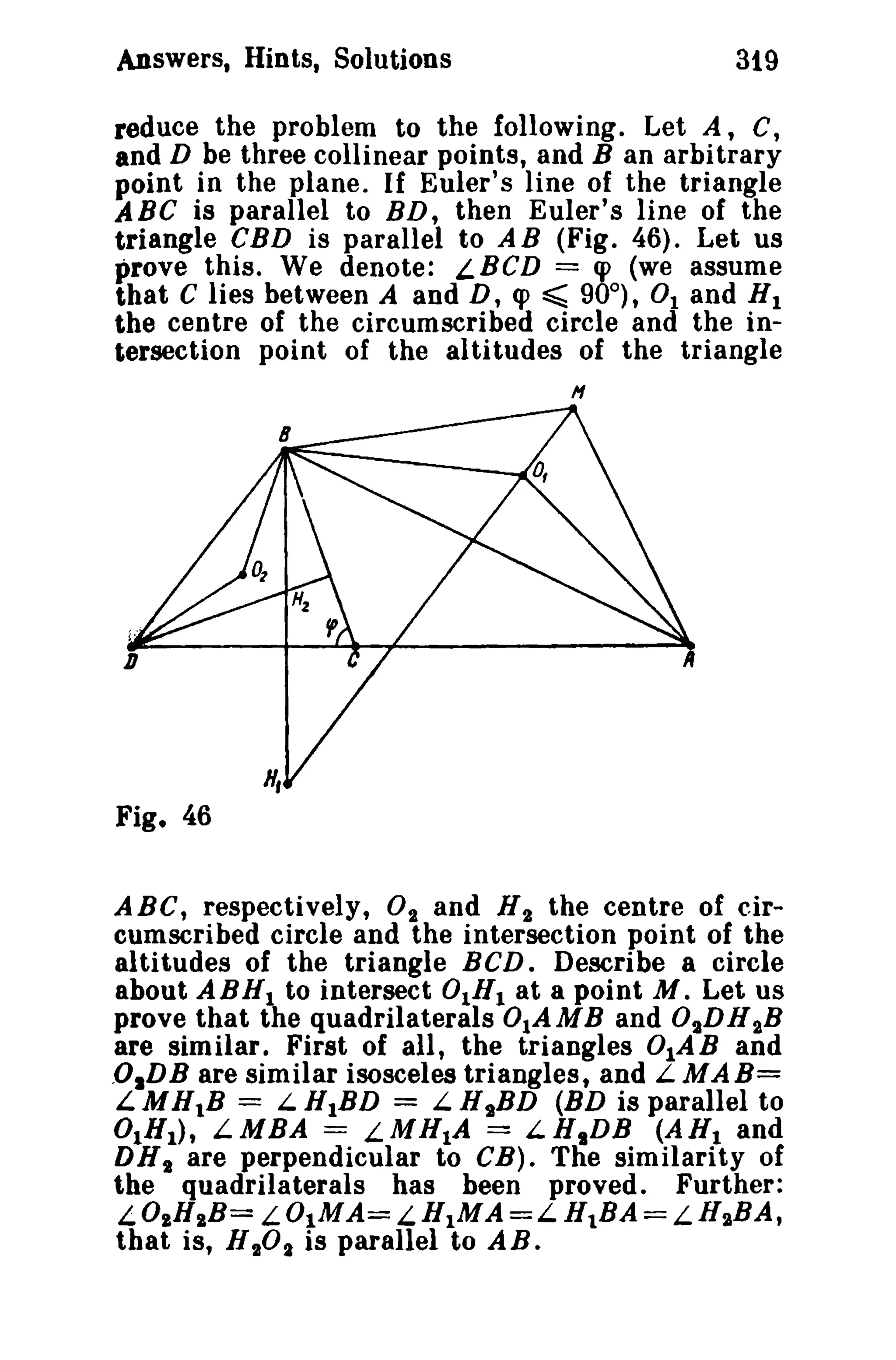

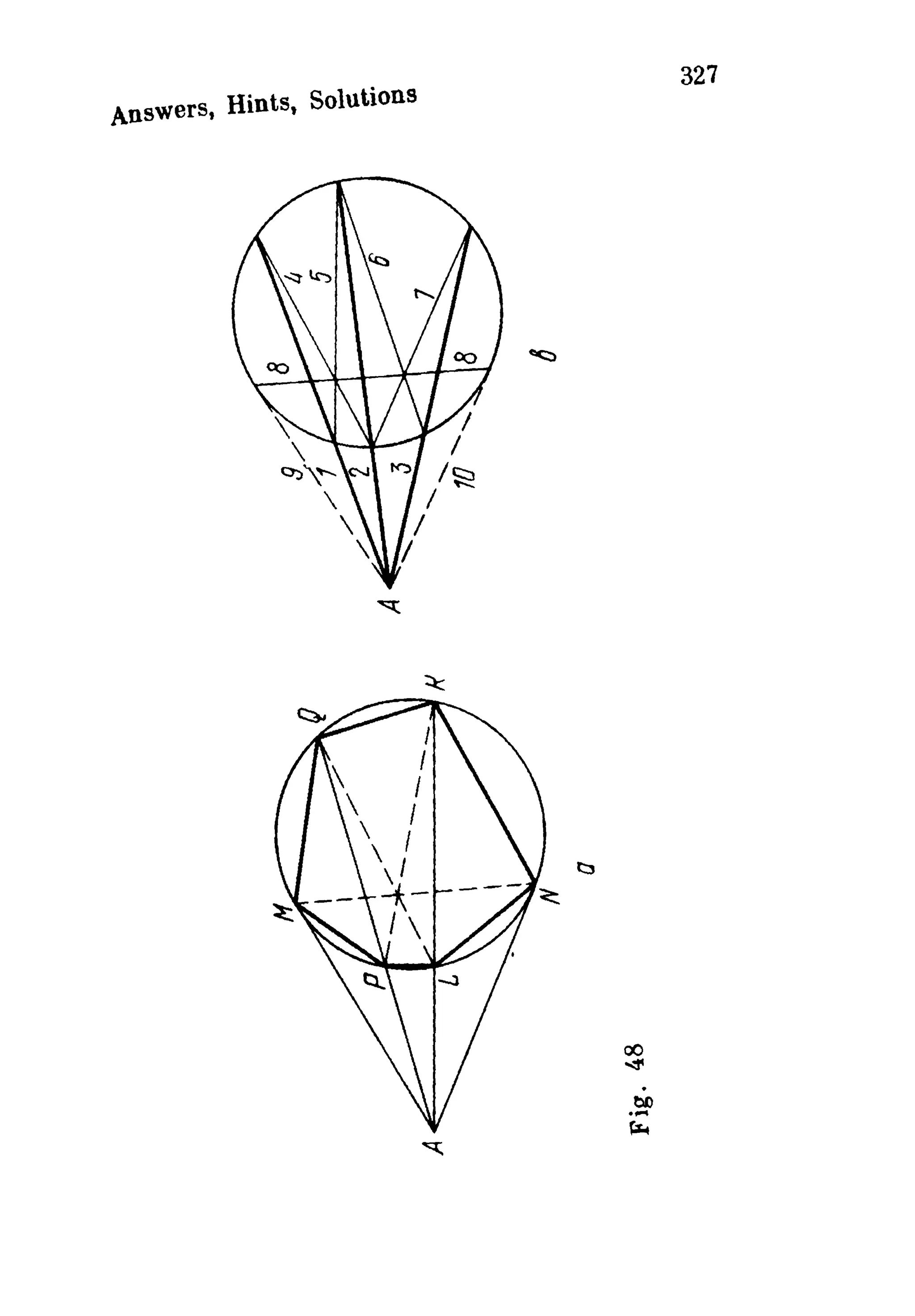

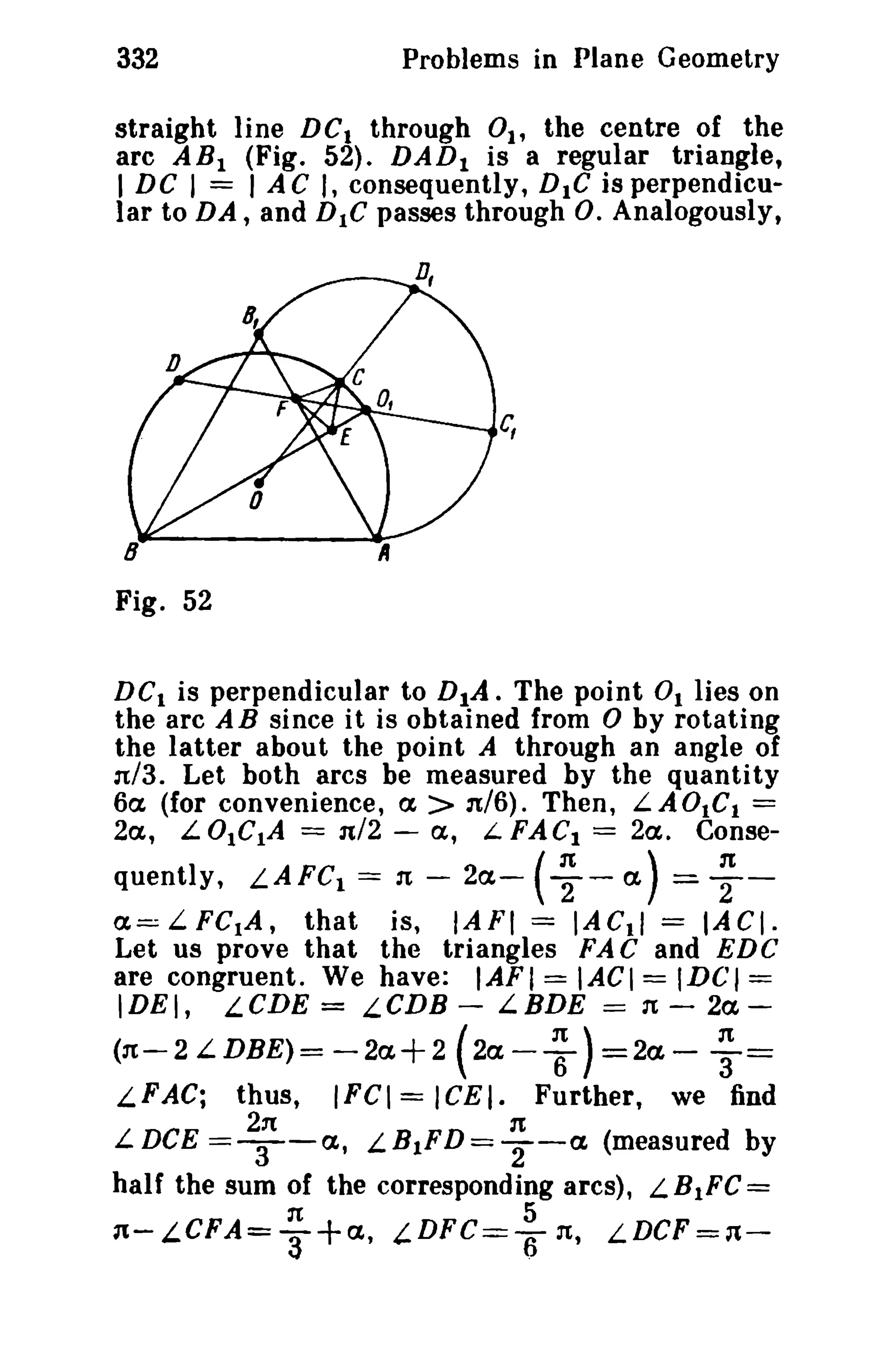

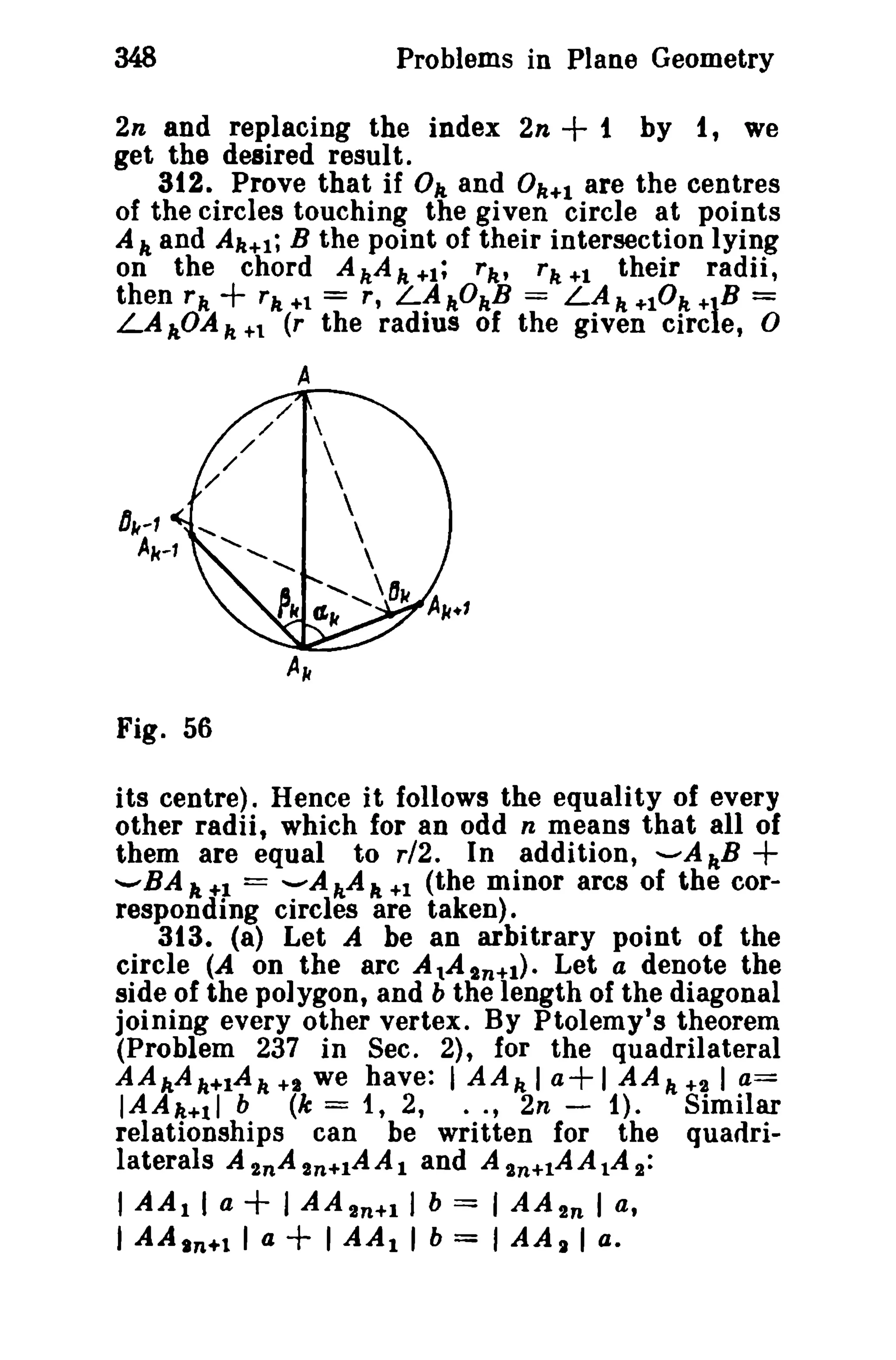

257. Let us prove that the triangle eMN is

similar to the triangle CAB (Fi'g. 9). We have:

CF------+--+-~--_14

LMCN = LeBA. Since the quadrilateral CBDM

· . ibed h ICMI sin L CBM

is an insert one, we ave ICBI sin L CMB=

sin L CDM sin L DBA IADI ICNI

sin L CDB = sin L ADB =~=lAIiI·](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-140921124347-phpapp02/75/SHARIGUIN_problems_in_plane_geometry_-199-2048.jpg)

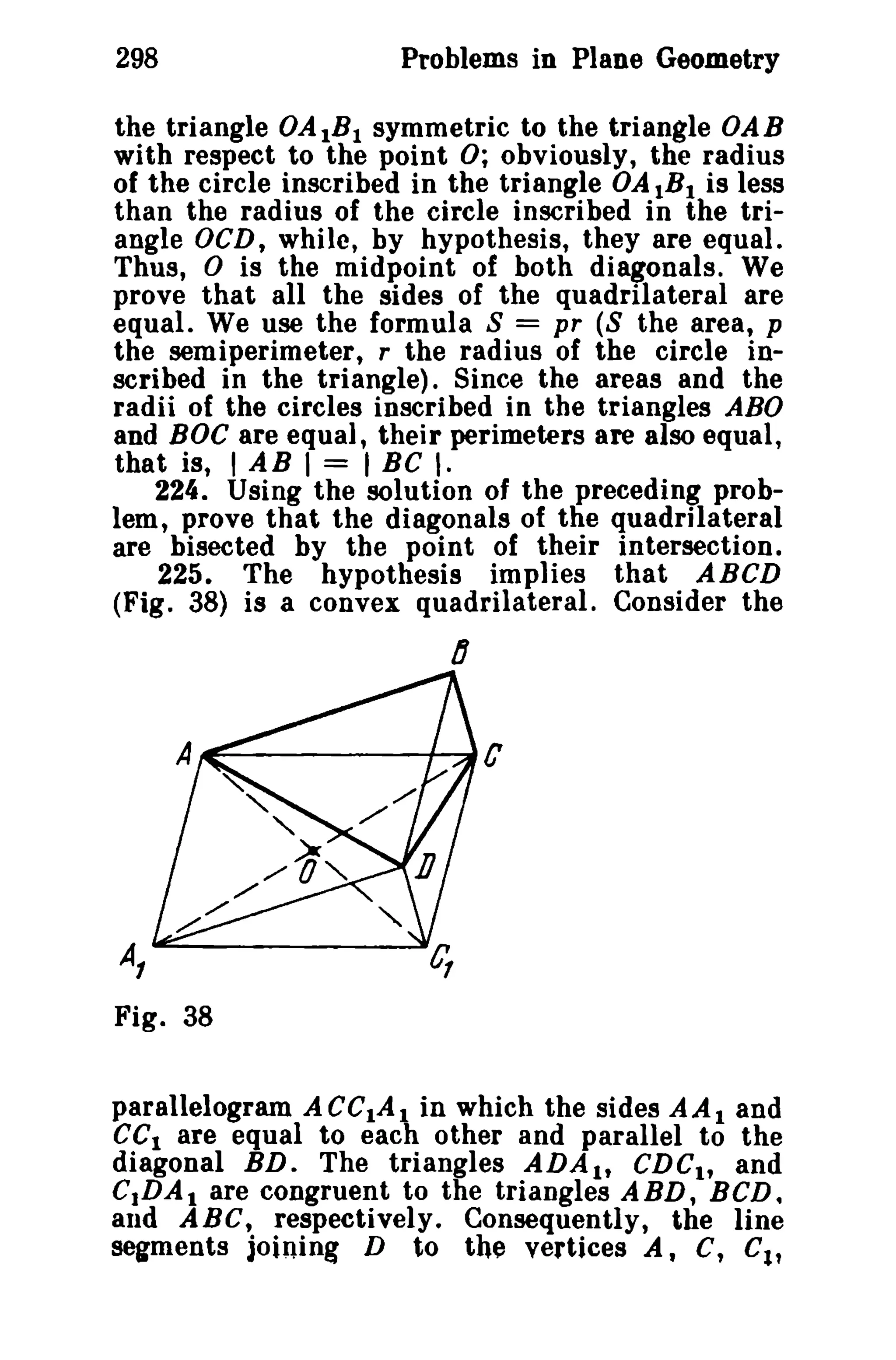

![294 Problems in Plane Geometry

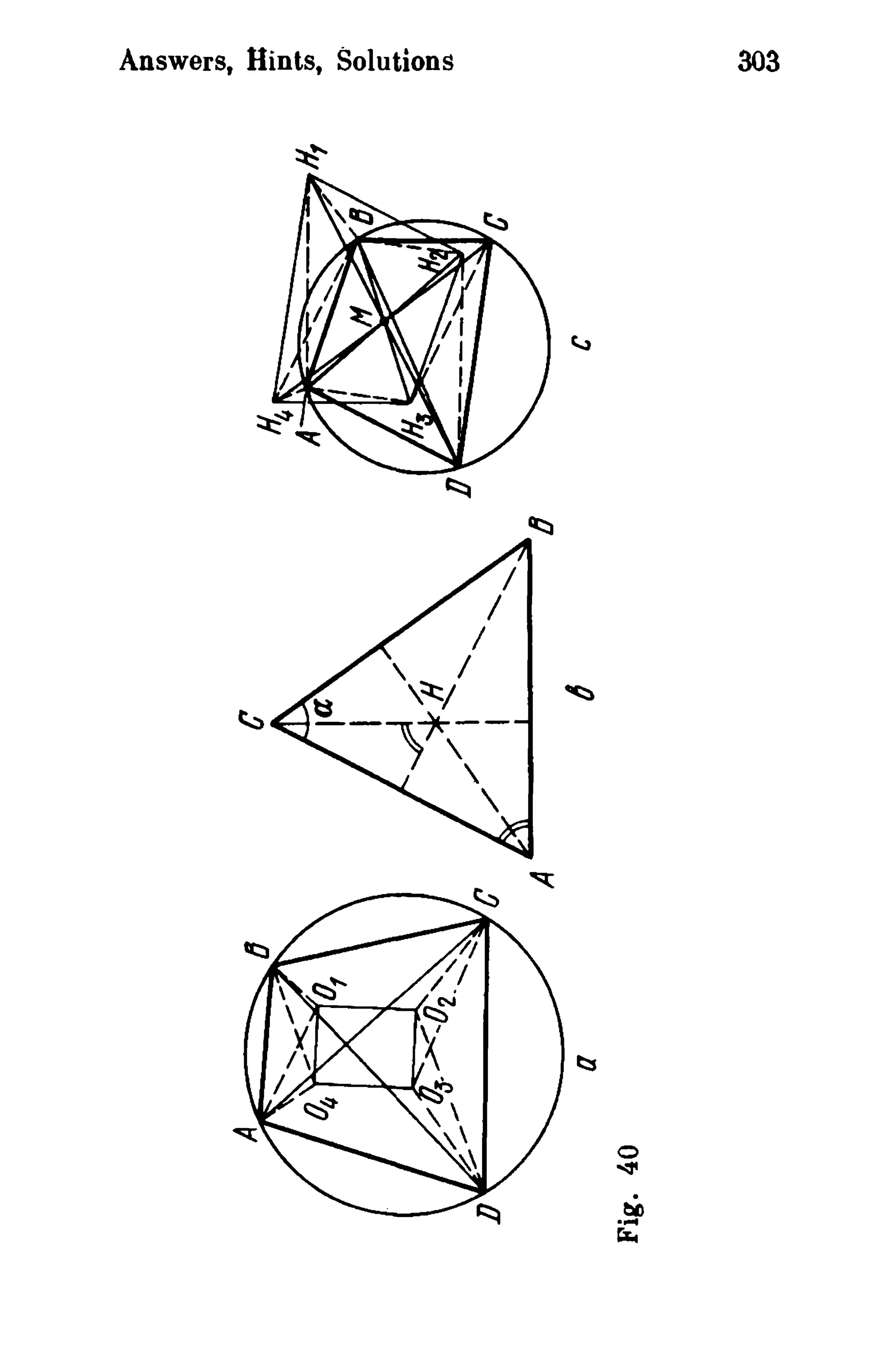

209. Notation: ABC is the given triangle, M

the point situated at a distance d from the centre

of the circle circumscribed about the triangle ABC,

A I' B l' and C1 the feet of the perpendiculars dropped

from M on BC, CA, and AB; At. B 2 , C2 the

intersection points of AM, BM, CM with the

circle circumscribed about the triangle ABC, respectively,

a, b, and c the sides of the triangle

ABC, ai- bh Cl and at, bi , C2 the sides of the triangles

AlBICt and A~BiC2' respectively; S, Sit

and 8,. the areas of those triangles, respectively.

We have:

al=IAMI sinA=IAMI 2~' (1)

The sides bl and CI are found in a similar way.

From the similarity of the triangles B and

2MC2 BMC, we get:

at IBIMI

ICMI

(2)

a Analogous ratios are obtained for ~2 and :2

The triangles AlBIC] and AtB2C,. are similar (see

Problem 207 of Sec. 2); in addition,

8 2 al b2c? (3)

s=libC

Bearing all this in mind, we have:

(~) 3 ==~. S~ = aibtc~ • a~b~c~

S 81 83 alb~cl a3b3c3

=(_1_)3 IAMIIIBMI'ICMI2 a2b2cl

4R2 a3b3c3 •a2b2c2

= ( 4~2 )3 IAMI 2 1BMI21CMI2

X IB2M I IC2MI IAIMI (_1_IRI_d21)3

ICMI IAMI IBMI 4R2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-140921124347-phpapp02/75/SHARIGUIN_problems_in_plane_geometry_-297-2048.jpg)

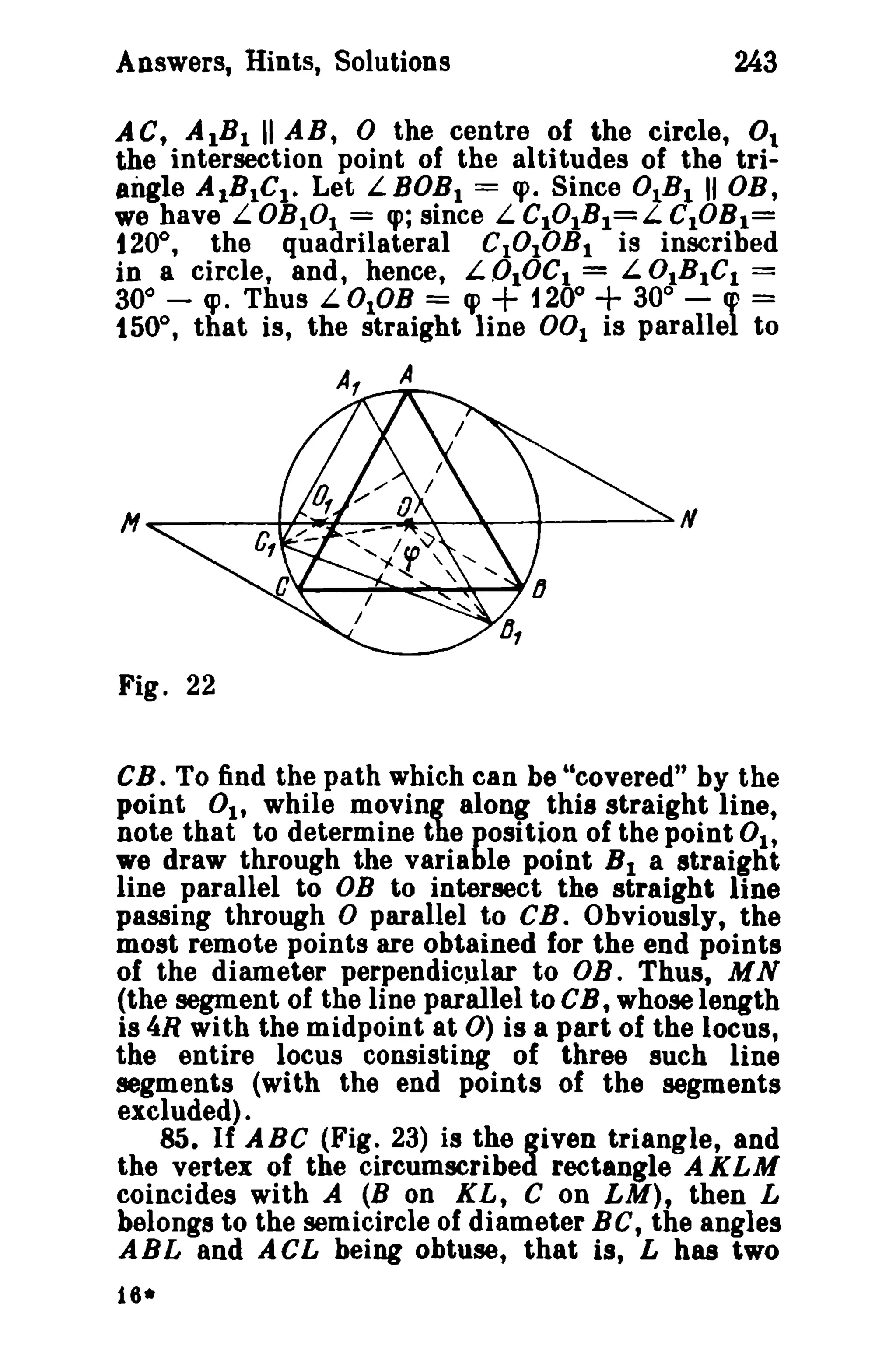

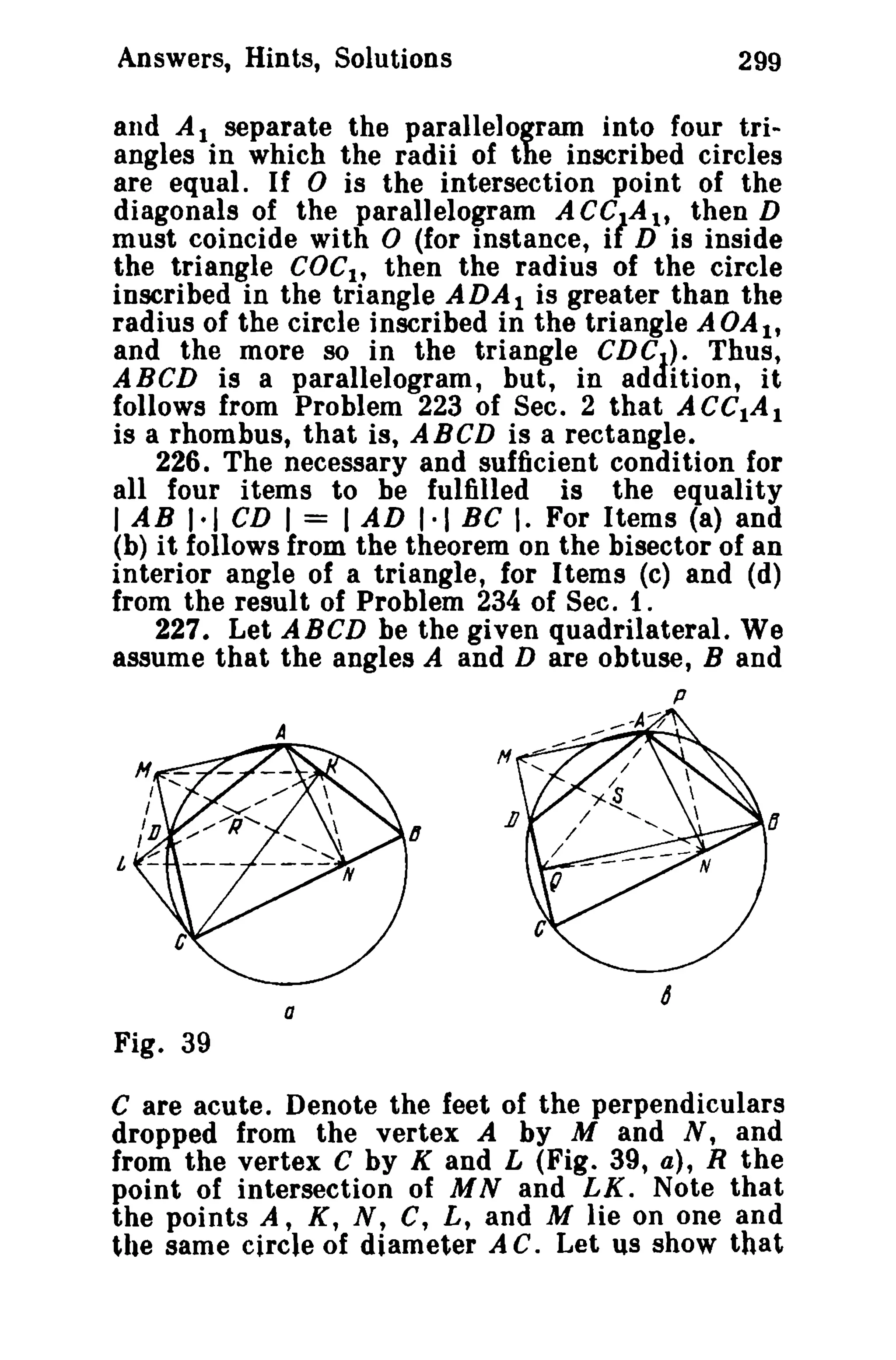

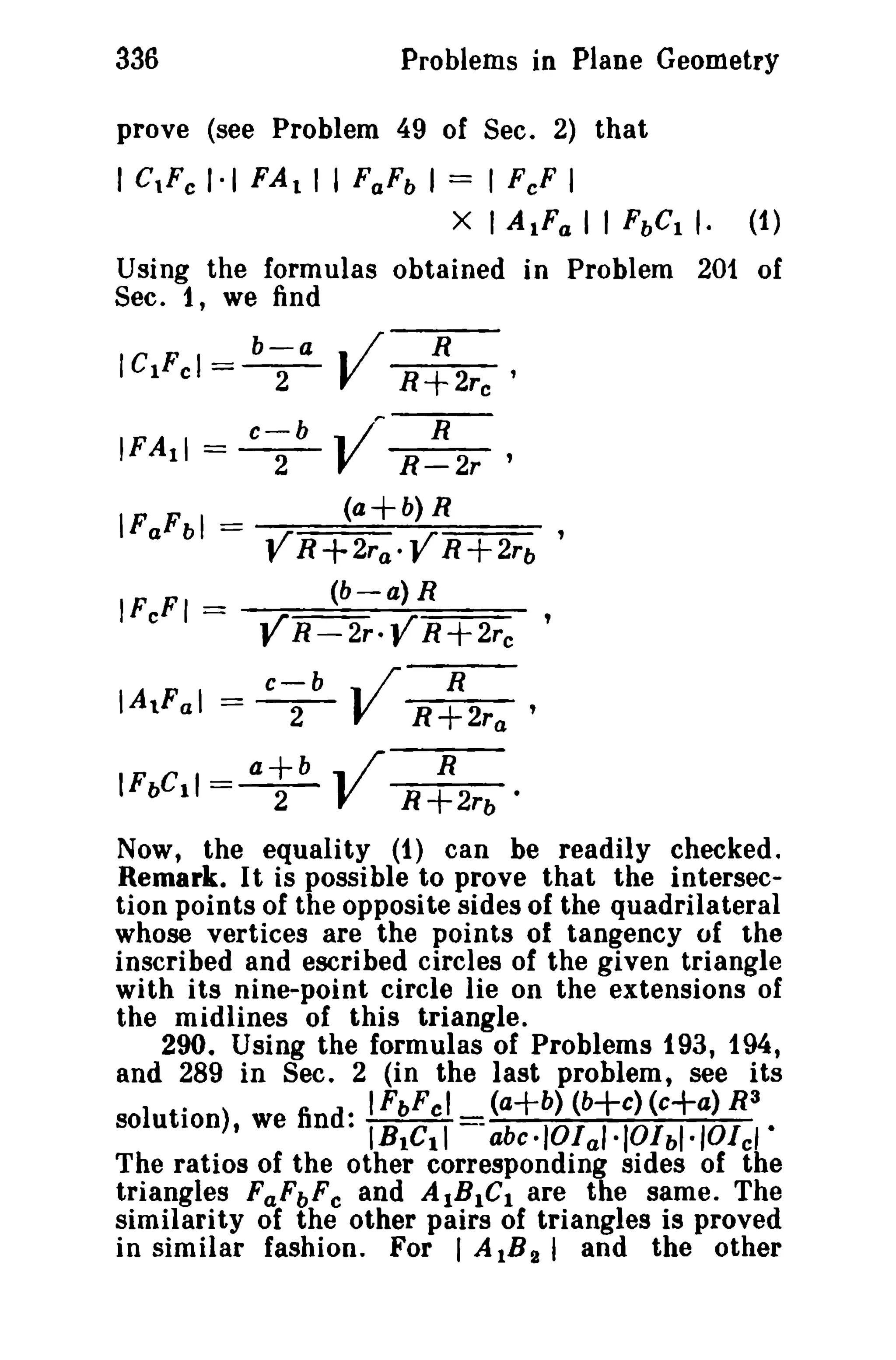

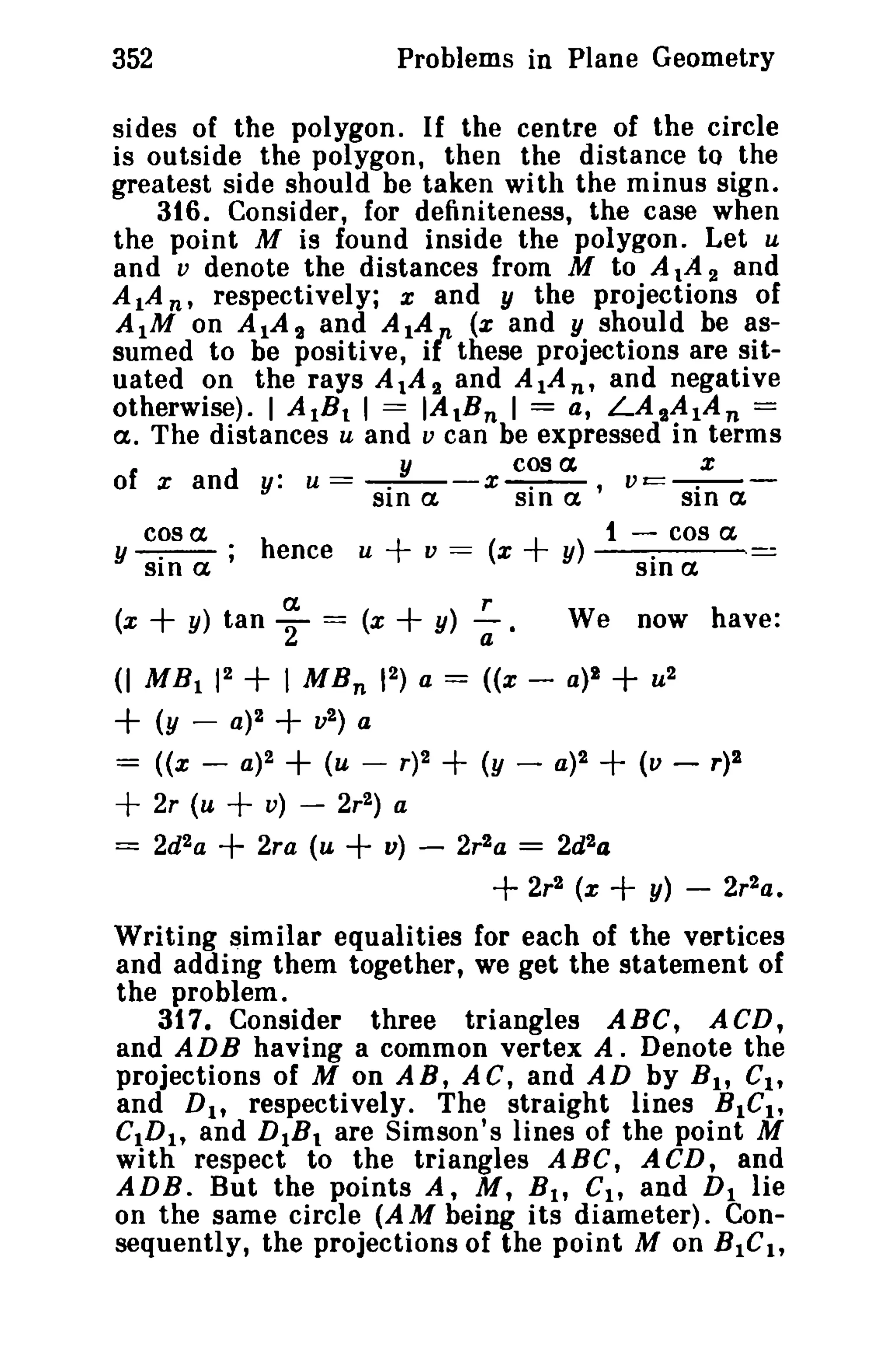

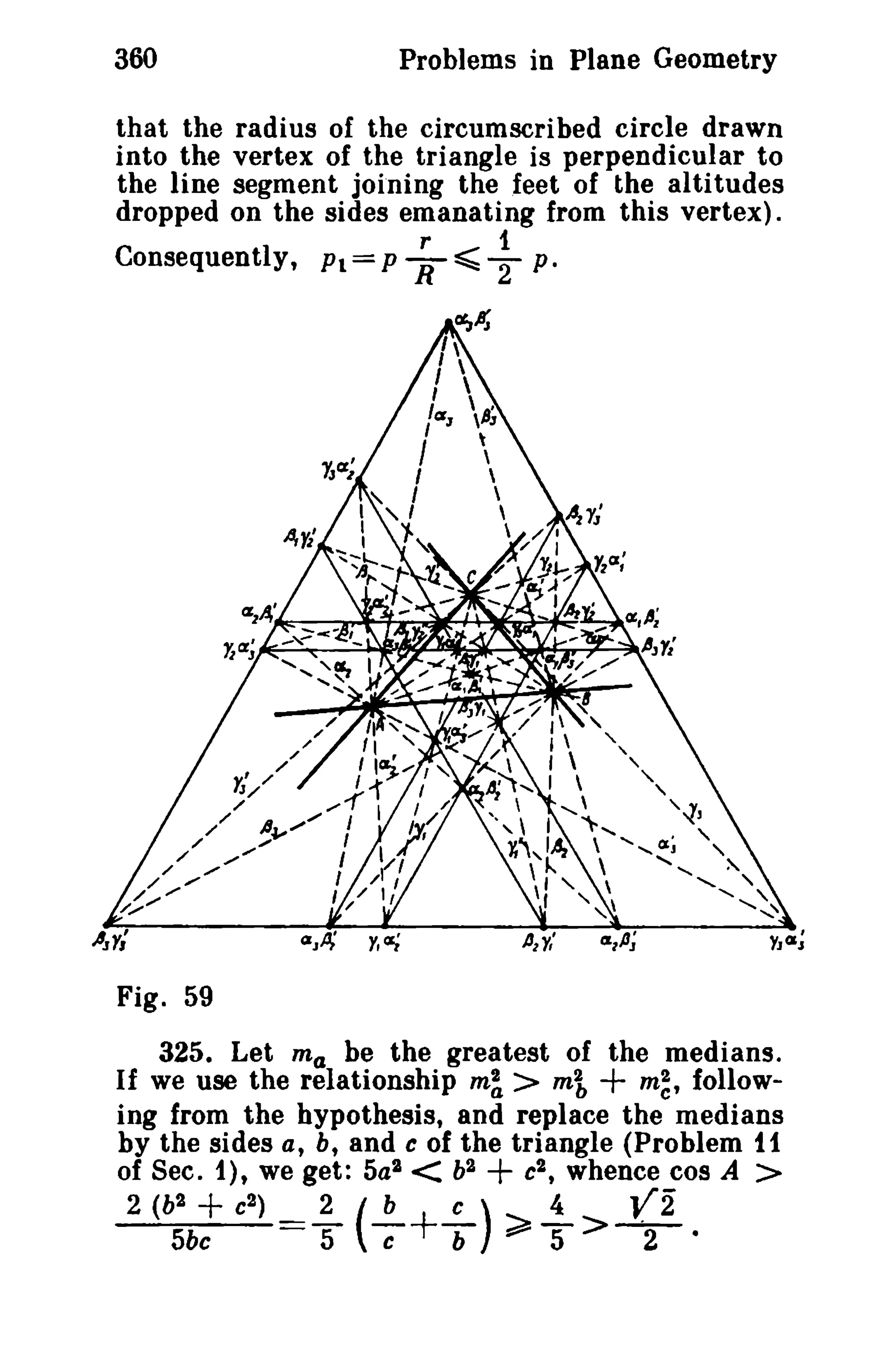

![Answers, Hints, Solutions 367

ball. This number is equal to [ : ] +1 if : is

not a whole number ([xl the integral part of the

number z}; if ~ is a whole number, then it is a

equal to the maximal number of reflections.

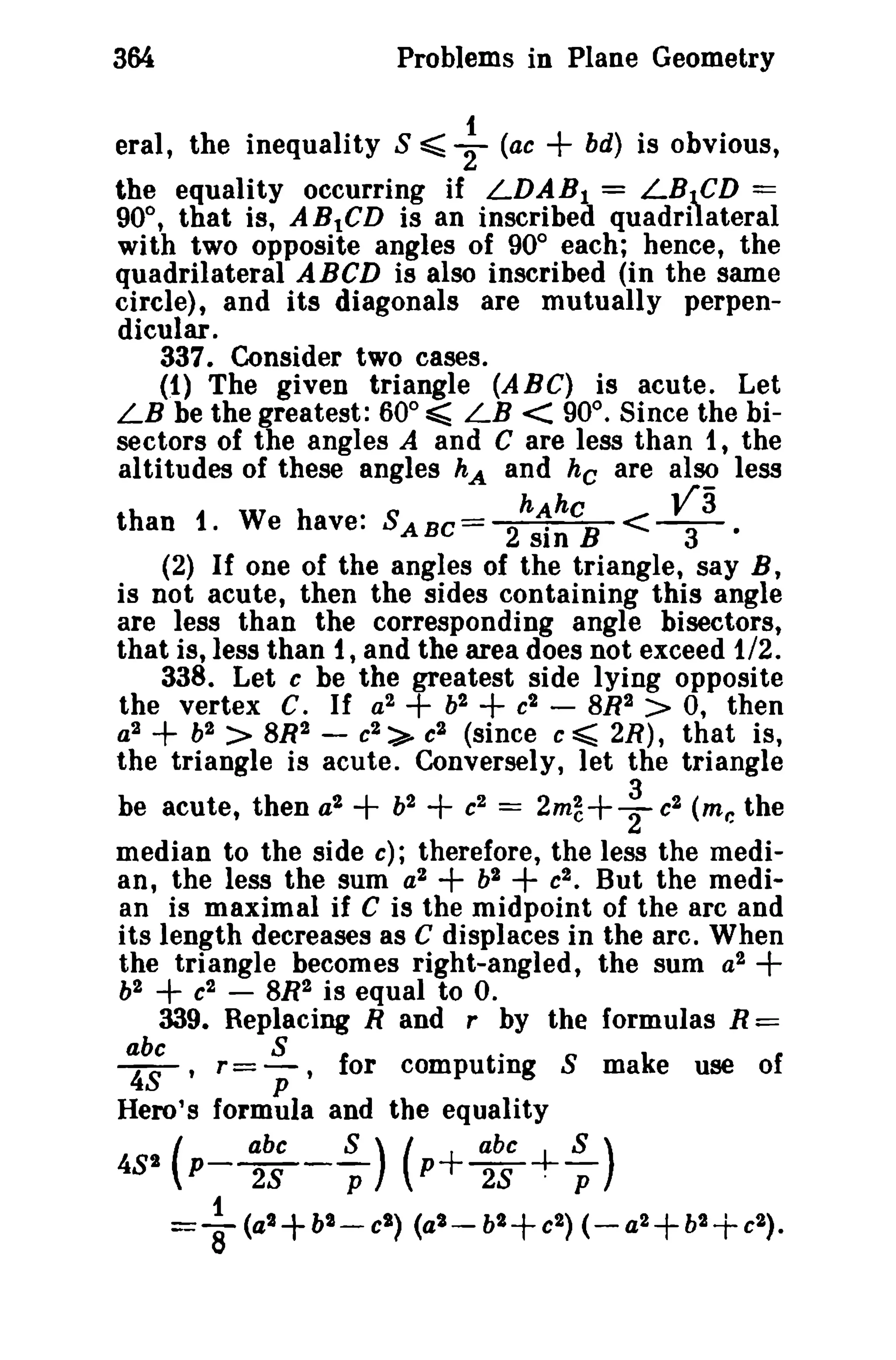

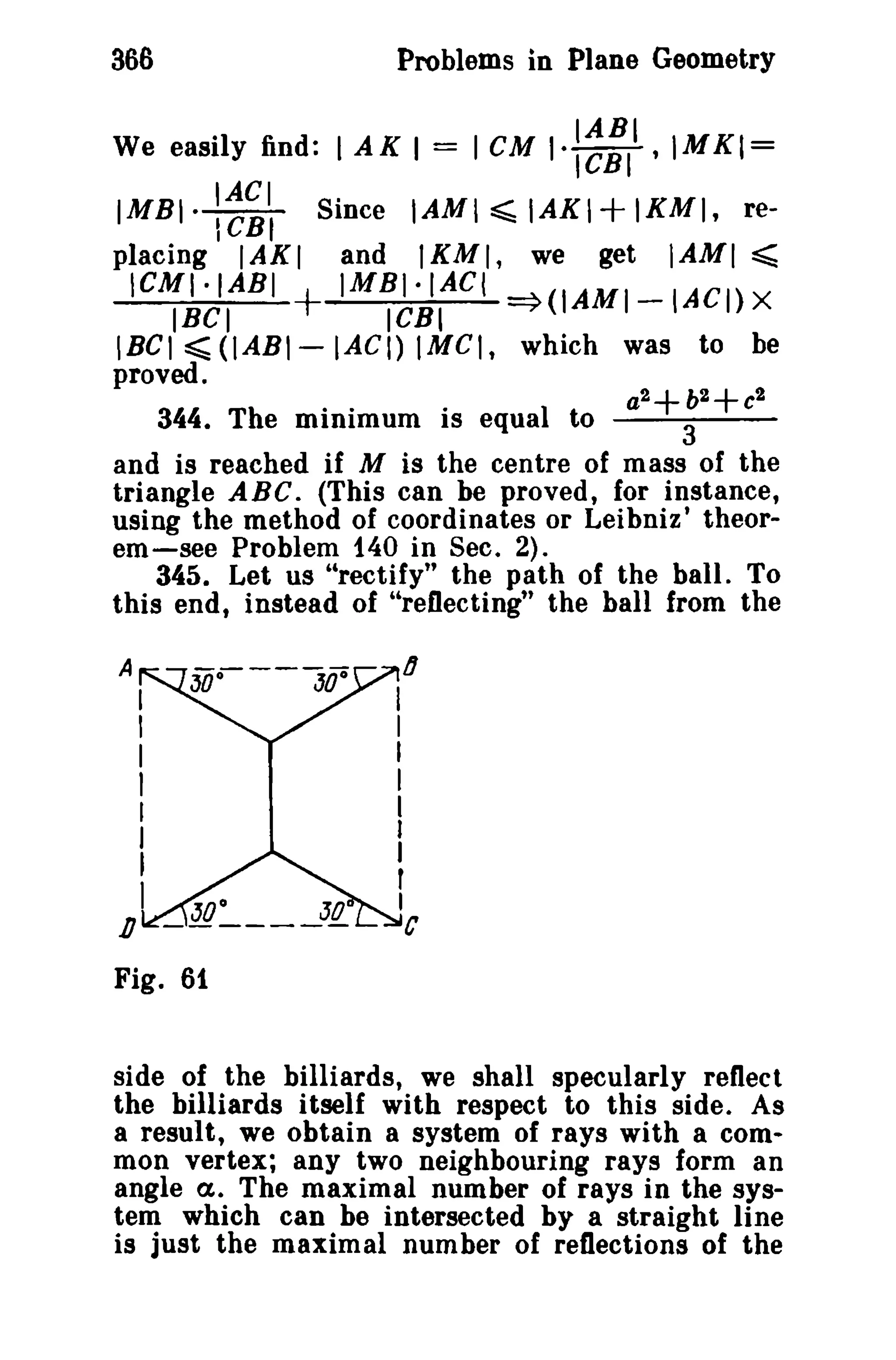

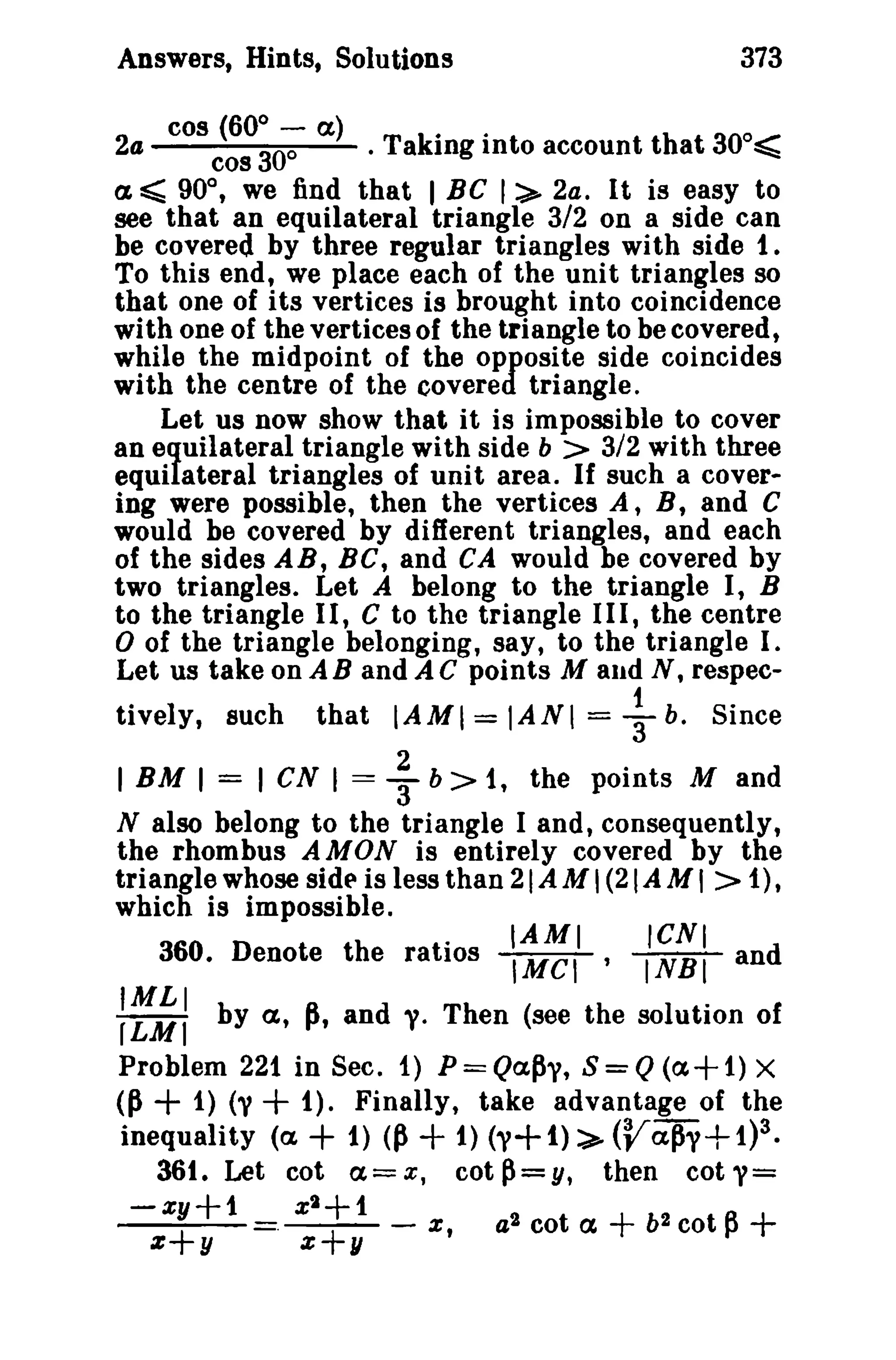

346. If the roads are constructed as is shown in

Fig. 61 (A, B, C and D denote the villages, and

the roads are shown by continuous lines), then

their total length is 2+ 2 Y3< 5.5. It is possible

to show that the indicated arrangement of the roads

realizes the minimum of their total length.

347. If one of the sides of the triangle through

A forms an angle q> with the straight line perpendicular

to the given parallel straight lines, then

the other side forms an angle of 1800

- q> - ex;

on having found these sides, we get that the area

of th e trriiangIe'IS equaI to 2 ab sin (a + ) cos q> cos cp ex

tal- sin ex This expression is

cos a + ~s (a + 2q»

minimal if ctl + 2q> = 1800

•

a.

Answer: $'ftiln = ab cot '"2.

IABI

348. We have: SACBD= IMOI SOCD =

2 (k+1) SOCD. Consequently, SABCD is the greatest

if the area of the triangle OeD is the greatest.

But OCD is an isosceles triangle with lateral side

equal to R, hence, its area is maximal when the

sine of the angle at the vertex 0 reaches its maximum.

Let us denote this angle by q>. Obviously

q> ~ q> < n, where «Po corresponds' to the case

wten AB and CD are mutually perpendicular.

Consequently, if CPo ~ n/2, then the maximal area

of the triangle OCD corresponds to the value q>t =

n/2, and if <Po > n/2, then to the value fJ't = (J'o.

Answer: if s«; V2-1, then Smax=(k+1) R2;

if k ;» l/2-1, then Smax=2R2 Yk (k+2)/(k+1).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-140921124347-phpapp02/75/SHARIGUIN_problems_in_plane_geometry_-370-2048.jpg)

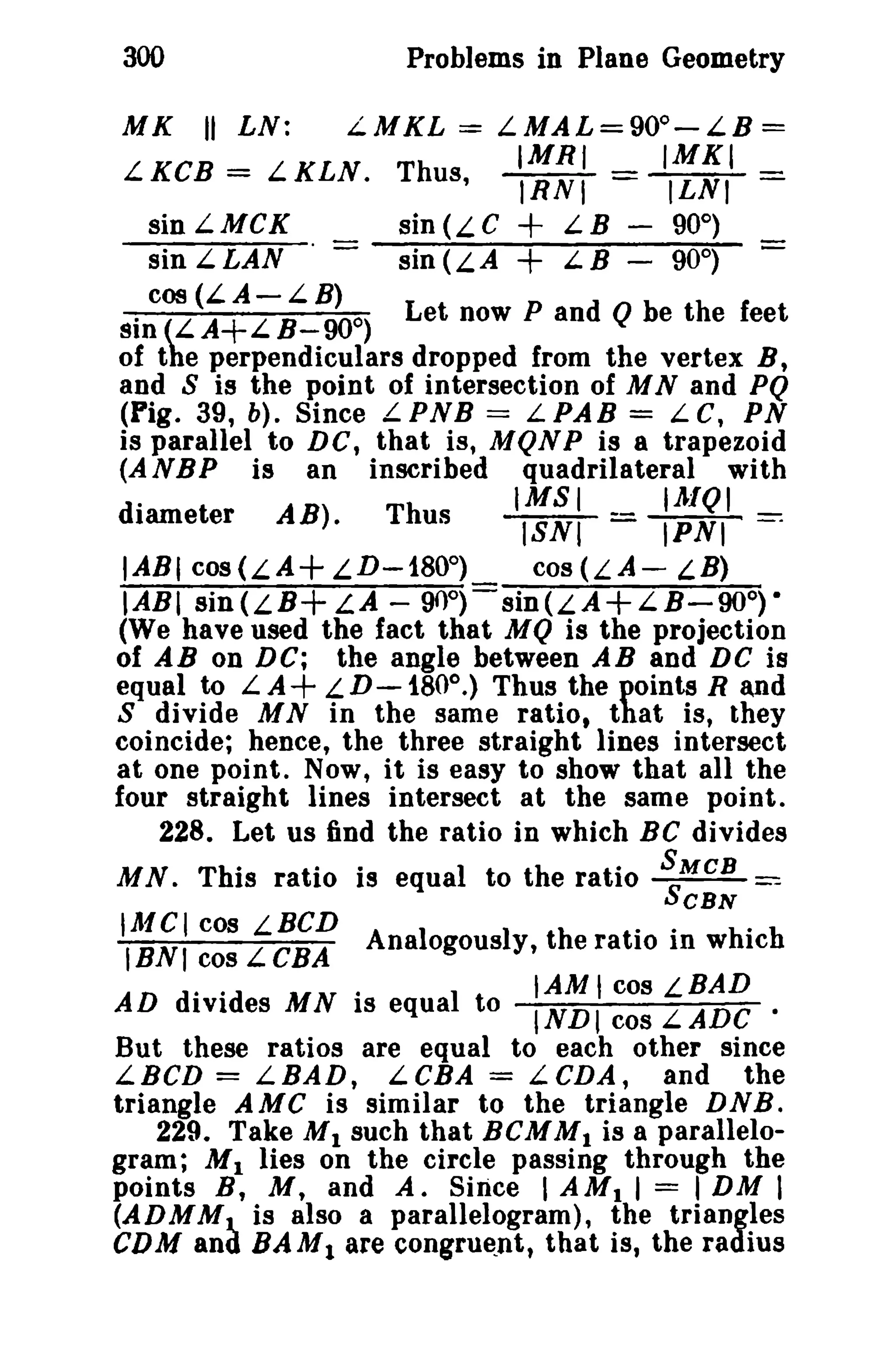

![382 Problems in Plane Geometry

from the property of the angle bisector, see Problem

9 in Sec. 1):

~ -+- -+

IA·a + IB·b + IC-e = O. (1)

In addition, I IB I < c, I tc I < b. These inequalities

follow from the fact that the angles AlB

and AIC are obtuse. Let us take a point Al sufficiently

close to the point A so that the inequalities

are fulfilled as before: I ItB I < c, I le I <

bt where II is the centre of the circle inscribed in

the triangle A tBC. The sides of the triangle A IBC

are equal to at bl , CI. The same as for the triangle

ABC, we write the equality

-+- ~ ~

I 1At·a+ItB.b1+/tC.cl =0.

Subtract (1) from (2):

(2)

--+- -. --+- -. ~ --+-

a (I lAt - I A)+ IIB·b t - I B·b+ / lC·Ct-1C.c= O.

(3)

Note that

-.. --+- -+- --+I

1A1-IA=/1/+AAt ,

-.. -+ --+- -+

I IB.bl- IB·b-/tB (b1-b)+I.I·b,

(4)

(5)

--.... -+ ~ --+

I Ie·CI- IC ·c+ I Ie (CI- c)+11/ -c, (6)

Replacing in (3) the corresponding differences

by the formulas (4), (5), (6), we get

--+- -+--+

I II (a+ b+c)+AA1 -a+liB (bl - b)

--+

+/tC (Cl- c)=O.

-+ -+

Since 1/1BI <c, IItCI <b, Ibl-hl < IAIAI,

~ 1

ICl - cl < IAIAI, we have: I/t/l a+b+c X

--+ -+ -+

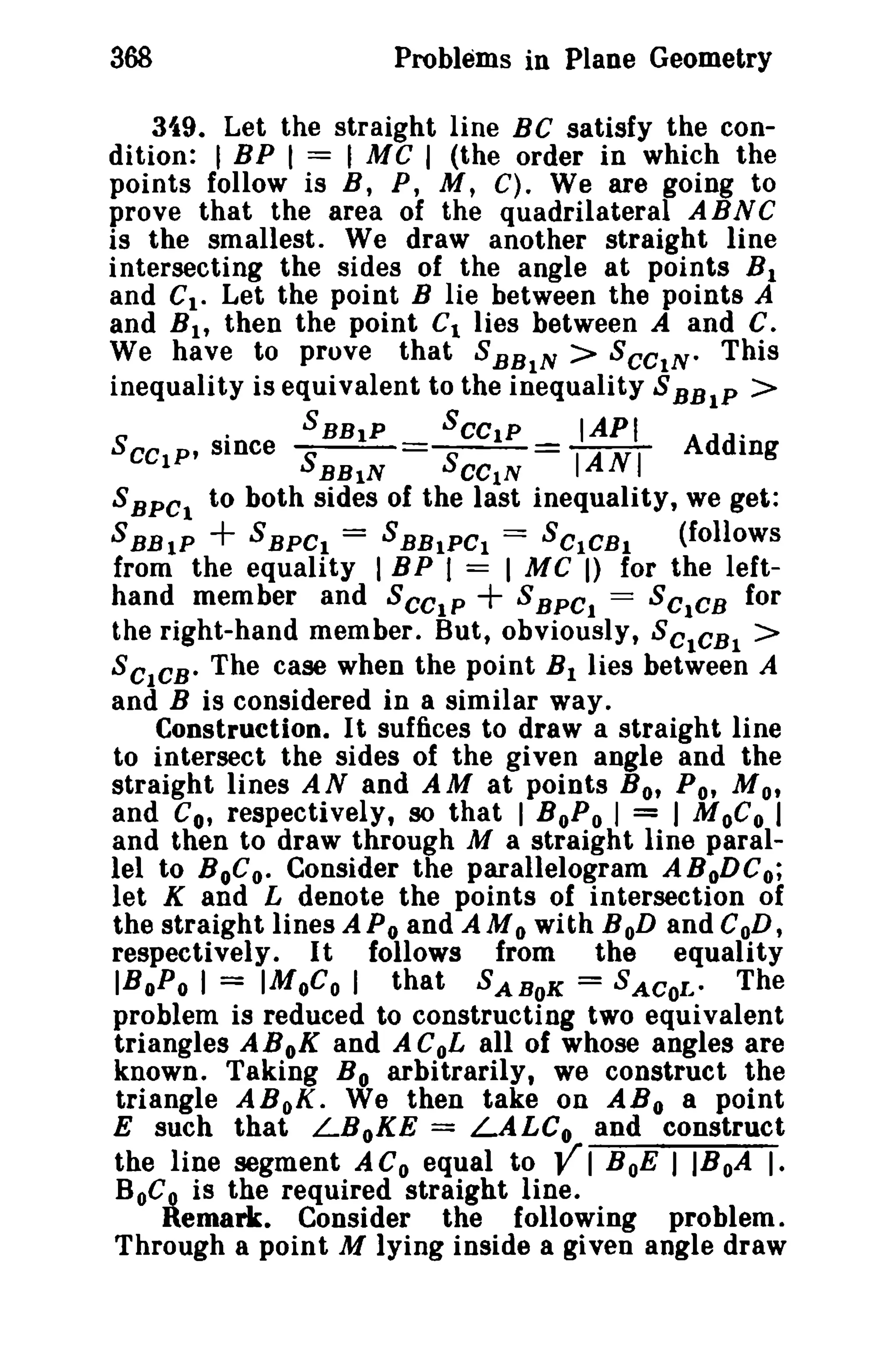

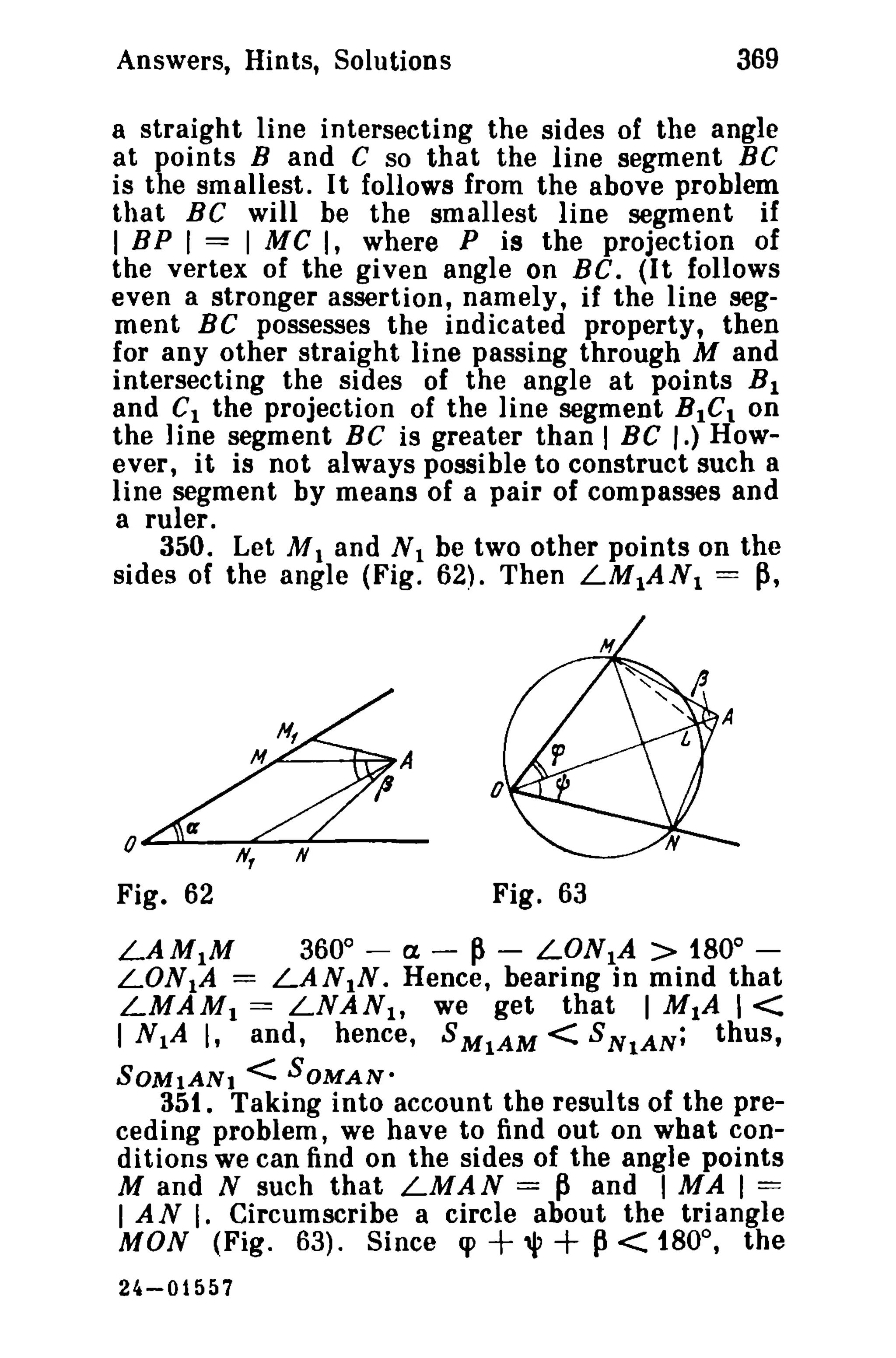

fAAt·a + I 1B(bl - b) + I1C(Cl - e)] < IAAtl X](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/i-140921124347-phpapp02/75/SHARIGUIN_problems_in_plane_geometry_-385-2048.jpg)