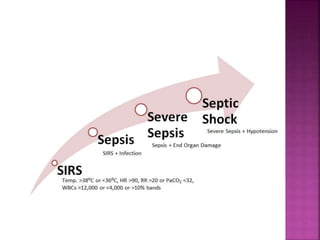

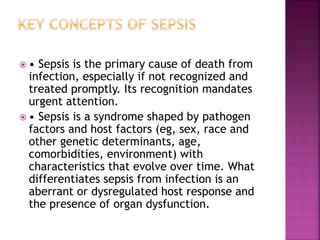

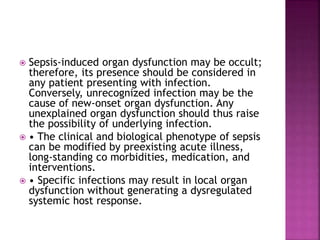

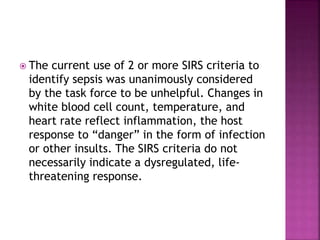

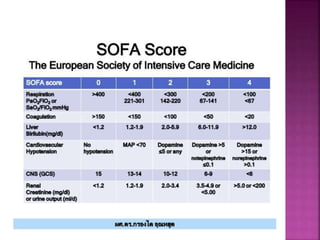

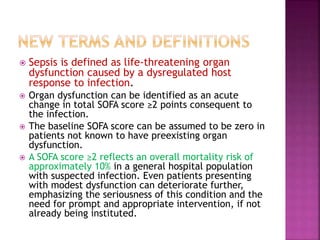

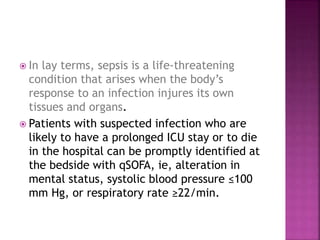

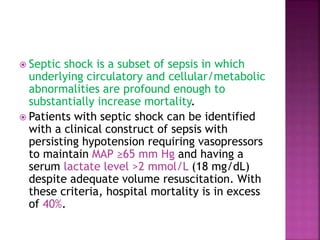

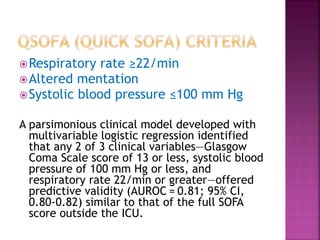

The document summarizes the key findings and conclusions from a task force that updated the definitions of sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). The task force convened experts who engaged in iterative discussions to address limitations of previous definitions. The new definitions define sepsis as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection, and septic shock as a subset of sepsis with profound circulatory and metabolic abnormalities. A quick bedside score (qSOFA) was also developed to help identify patients likely to face poor outcomes.