This document discusses various elements of sentence structure and grammar, including:

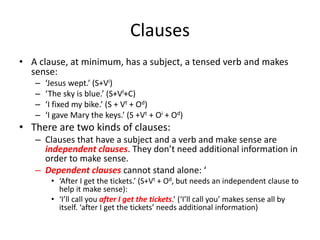

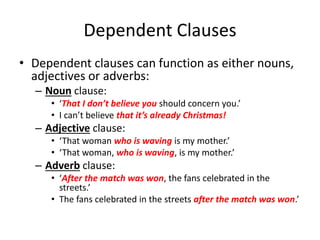

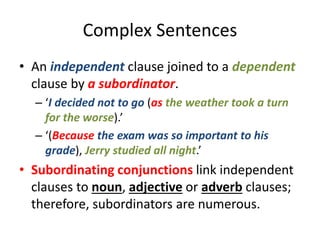

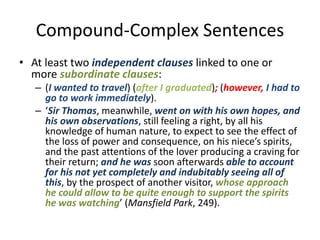

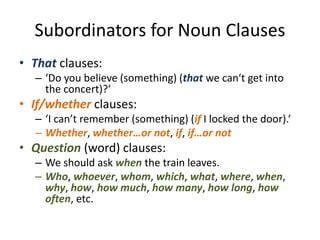

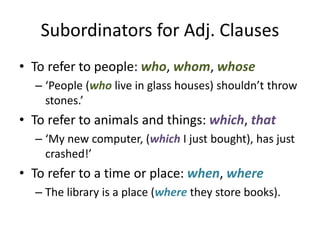

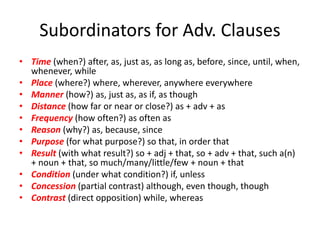

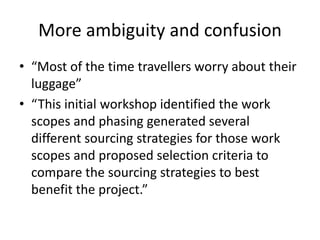

- Clauses can be either independent or dependent, with dependents functioning as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs.

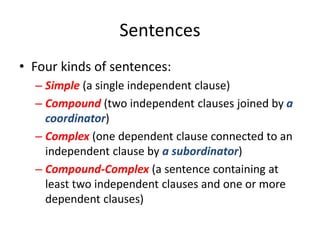

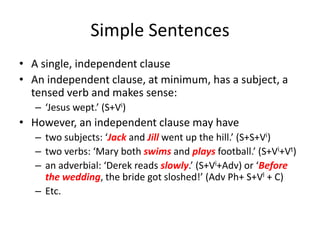

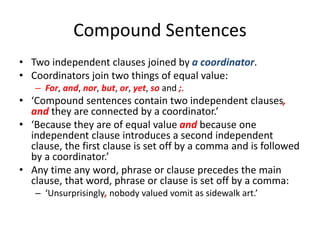

- There are four types of sentences - simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex.

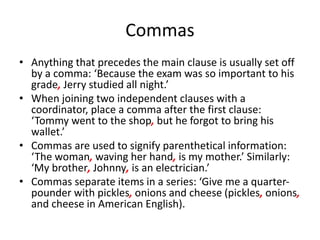

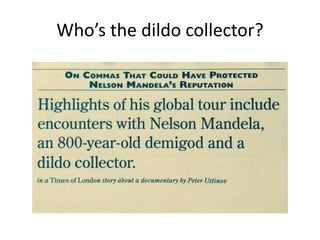

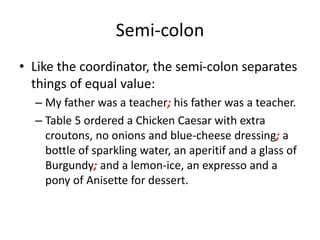

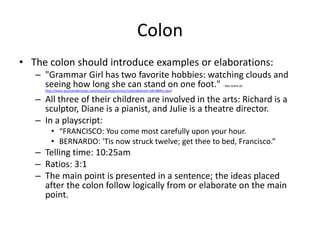

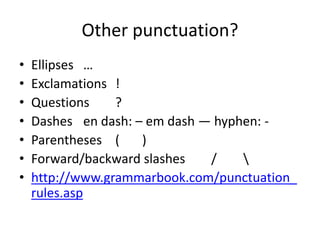

- Various punctuation is discussed like commas, semicolons, colons, ellipses, and dashes.

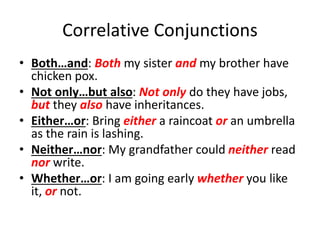

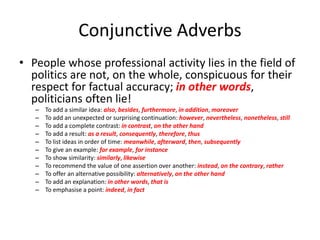

- Conjunctions like coordinators, subordinators, and correlative conjunctions are explained.