The document introduces concepts related to vector spaces including vectors, linear independence, and subspaces. It provides examples in R3 involving determining if sets of vectors are linearly dependent or independent, finding representations of vectors as linear combinations of other vectors, and solving homogeneous and nonhomogeneous systems of equations involving vector coefficients. Key concepts are illustrated through a series of problems involving vectors in R3.

![1 4 3

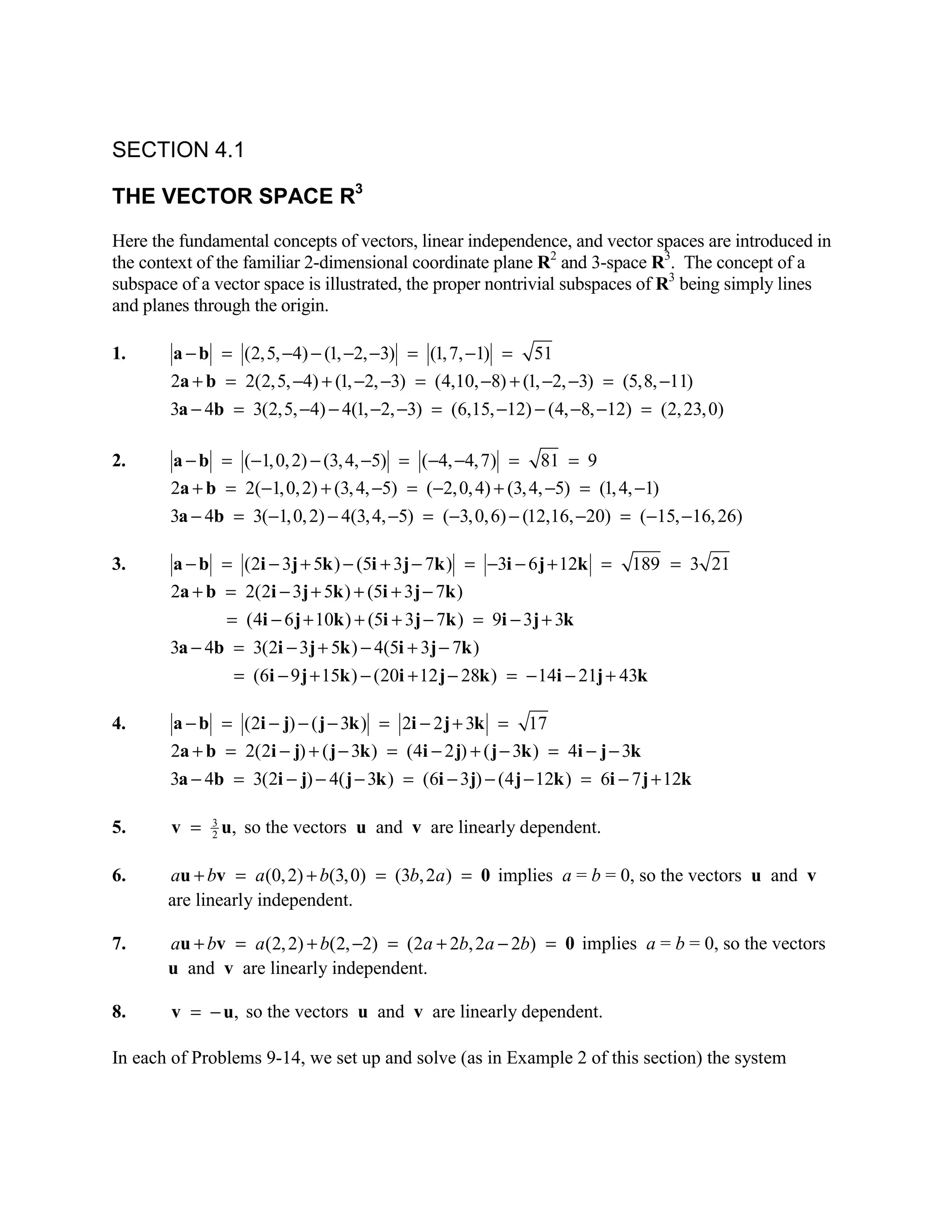

18. 1 3 −2 = 9 ≠ 0 so the three vectors are linearly independent.

0 1 −4

In Problems 19-24, we attempt to solve the homogeneous system Ax = 0 by reducing the

coefficient matrix A = [u v w ] to echelon form E. If we find that the system has only the

trivial solution a = b = c = 0, this means that the vectors u, v, and w are linearly independent.

Otherwise, a nontrivial solution x = [a b c ] ≠ 0 provides us with a nontrivial linear

T

combination au + bv + cw ≠ 0 that shows the three vectors are linearly dependent.

2 −3 0 1 0 −3

19. 0 1 −2 → 0 1 −2 = E

A =

1 −1 −1

0 0 0

The nontrivial solution a = 3, b = 2, c = 1 gives 3u + 2v + w = 0, so the three vectors

are linearly dependent.

5 2 4 1 0 2

20. 5 3 1 → 0 1 −3 = E

A =

4 1 5

0 0 0

The nontrivial solution a = –2, b = 3, c = 1 gives –2u + 3v + w = 0, so the three

vectors are linearly dependent.

1 −2 3 1 0 11

21. 1 −1 7 → 0 1 4 = E

A =

−2 6 2

0 0 0

The nontrivial solution a = 11, b = 4, c = –1 gives 11u + 4v – w = 0, so the three

vectors are linearly dependent.

1 5 0 1 0 0

22. 1 1 1 → 0 1 0 = E

A =

0 3 2

0 0 1

The system Ax = 0 has only the trivial solution a = b = c = 0, so the vectors u, v, and

w are linearly independent.

2 5 2 1 0 0

23. 0 4 −1 → 0 1 0 = E

A =

3 −2 1

0 0 1

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sect4-1-100319104237-phpapp01/85/Sect4-1-3-320.jpg)

![The system Ax = 0 has only the trivial solution a = b = c = 0, so the vectors u, v, and

w are linearly independent.

1 4 −3 1 0 0

24. 4 2 3 → 0 1 0 = E

A =

5 5 −1

0 0 1

The system Ax = 0 has only the trivial solution a = b = c = 0, so the vectors u, v, and

w are linearly independent.

In Problems 25-28, we solve the nonhomogeneous system Ax = t by reducing the augmented

coefficient matrix A = [u v w t ] to echelon form E. The solution vector

x = [a b c ] appears as the final column of E, and provides us with the desired linear

T

combination t = au + bv + cw.

1 3 1 2 1 0 0 2

25. −2 0 −1 −7 → 0 1 0 −1 = E

A =

2 1 2 9

0 0 1 3

Thus a = 2, b = –1, c = 3 so t = 2u – v + 3w.

5 1 5 5 1 0 0 1

26. 2 5 −3 30 → 0 1 0 5 = E

A =

−2 −3 4 −21

0 0 1 −1

Thus a = 1, b = 5, c = –1 so t = u + 5v – w.

1 −1 4 0 1 0 0 2

27. 4 −2 4 0 → 0 1 0 6 = E

A =

3 2 1 19

0 0 1 1

Thus a = 2, b = 6, c = 1 so t = 2u + 6v + w.

2 4 1 7 1 0 0 1

28. 5 1 1 7 → 0 1 0 1 = E

A =

3 −1 5 7

0 0 1 1

Thus a = 1, b = 1, c = 1 so t = u + v + w.

29. Given vectors (0, y , z ) and (0, v, w) in V, we see that their sum (0, y + v, z + w) and the

scalar multiple c(0, y, z ) = (0, cy, cz ) both have first component 0, and therefore are

elements of V.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sect4-1-100319104237-phpapp01/85/Sect4-1-4-320.jpg)