The document outlines a project plan for constructing a custom home for the Simpsons, featuring a 2,900-square-foot layout with 3 baths and 4 bedrooms, all within a $550,000 budget and a 7-month timeline. It details project scope, objectives, deliverables, milestones, and technical requirements to ensure successful completion while preventing scope creep. Key project management strategies emphasize balancing time, cost, and quality to meet customer satisfaction.

![Controller of the Universe, 2007

found tools and wire, 285 x 405 x 455 cm

Spotlight

100 Harvard Business Review January–February 2011

SPOTLIGHT ON BUSINESS MODEL INNOVATION

1568 JanFeb11 Casadesus-Masanell.indd 1001568 JanFeb11

Casadesus-Masanell.indd 100 12/3/10 3:52:19 PM12/3/10

3:52:19 PM

Joan E. Ricart ([email protected]

edu) is the Carl Schroder

Professor of Strategic Man-

agement and Economics

at IESE Business School in

Barcelona.

Ramon Casadesus-

Masanell ([email protected]

gmail.com) is an associate

professor at Harvard Busi-

ness School in Boston.

How to Design

A Winning

Business Model

Smart companies’ business models generate

cycles that, over time, make them operate

more eff ectively. by Ramon Casadesus-Masanell

and Joan E. Ricart](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadhousebuildingprojectplan-230125022624-d4343c3d/85/Running-head-HOUSE-BUILDING-PROJECT-PLAN-docx-7-320.jpg)

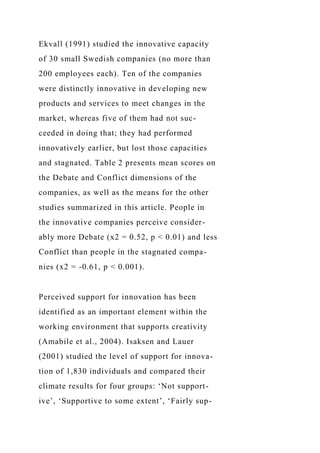

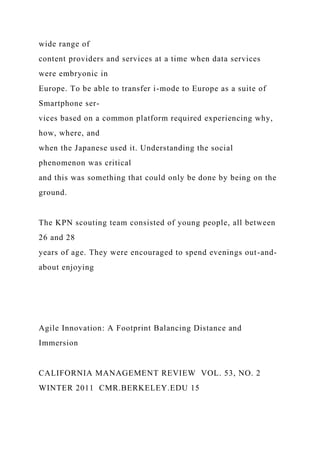

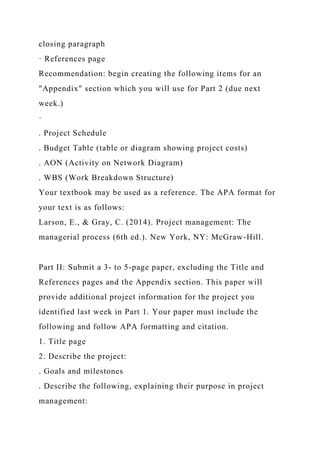

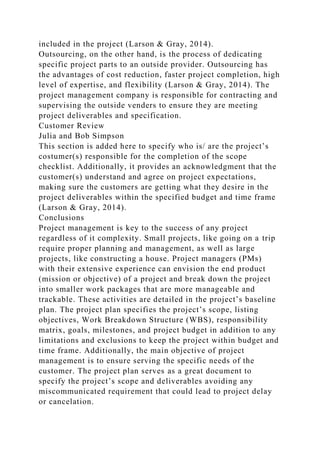

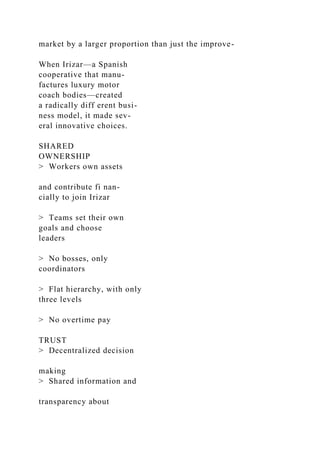

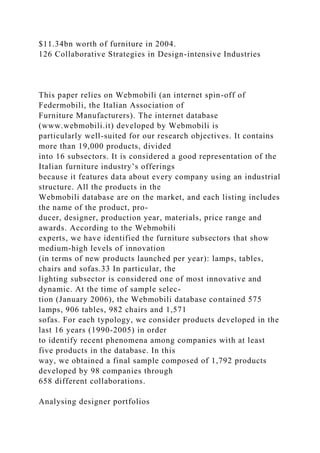

![Table 2. Designer portfolios - t test: Innovators vs. Imitators

Innovators Imitators T df

N 21 77

Osmosis 90.5% 76.6% �2.528* 69.328

Balanced Breadth 0.457 0.313 �2.973** 46.119

Foreign Backgrounda 45.7% 16.0% �4.847*** 89.000

Educational Background 0.716 0.432 �6.059*** 59.291

Industry Brokering 61.9% 51.1% �1.857 59.030

Subsector Brokering 2.234 1.736 �2.115* 96.000

*p < 0,05; **p < 0,01; ***p < 0,001.

a Including 70 imitators; 7 companies also have divisions

outside of Italy.

Long Range Planning, vol 43 2010 129

Figure 2. Osmosis e Innovators vs Imitators [radius is

proportional to the number of companies]

average number of external designers belonging to innovators’

portfolios is impressively higher than

that of the imitators’ portfolios (11.9 vs 4.4). For example,

innovators such as Artemide, Driade,

FontanaArte, Magis and Moroso collaborate with more than 15

freelance designers. Also, consid-

ering the ratio between the number of external designers and

number of products, innovators’

values are significantly higher than imitators’ metrics. As

mentioned in the Appendix, we have con-

sidered the contribution of the Gini dispersion index in the

definition of Balanced Breadth. This is

used to verify whether a company prefers to develop the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadhousebuildingprojectplan-230125022624-d4343c3d/85/Running-head-HOUSE-BUILDING-PROJECT-PLAN-docx-48-320.jpg)

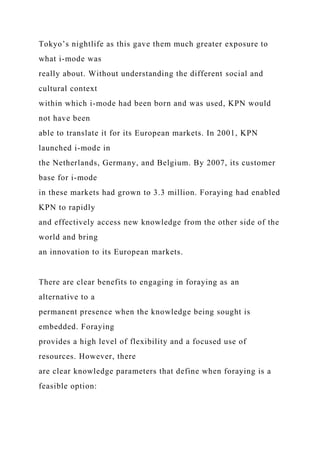

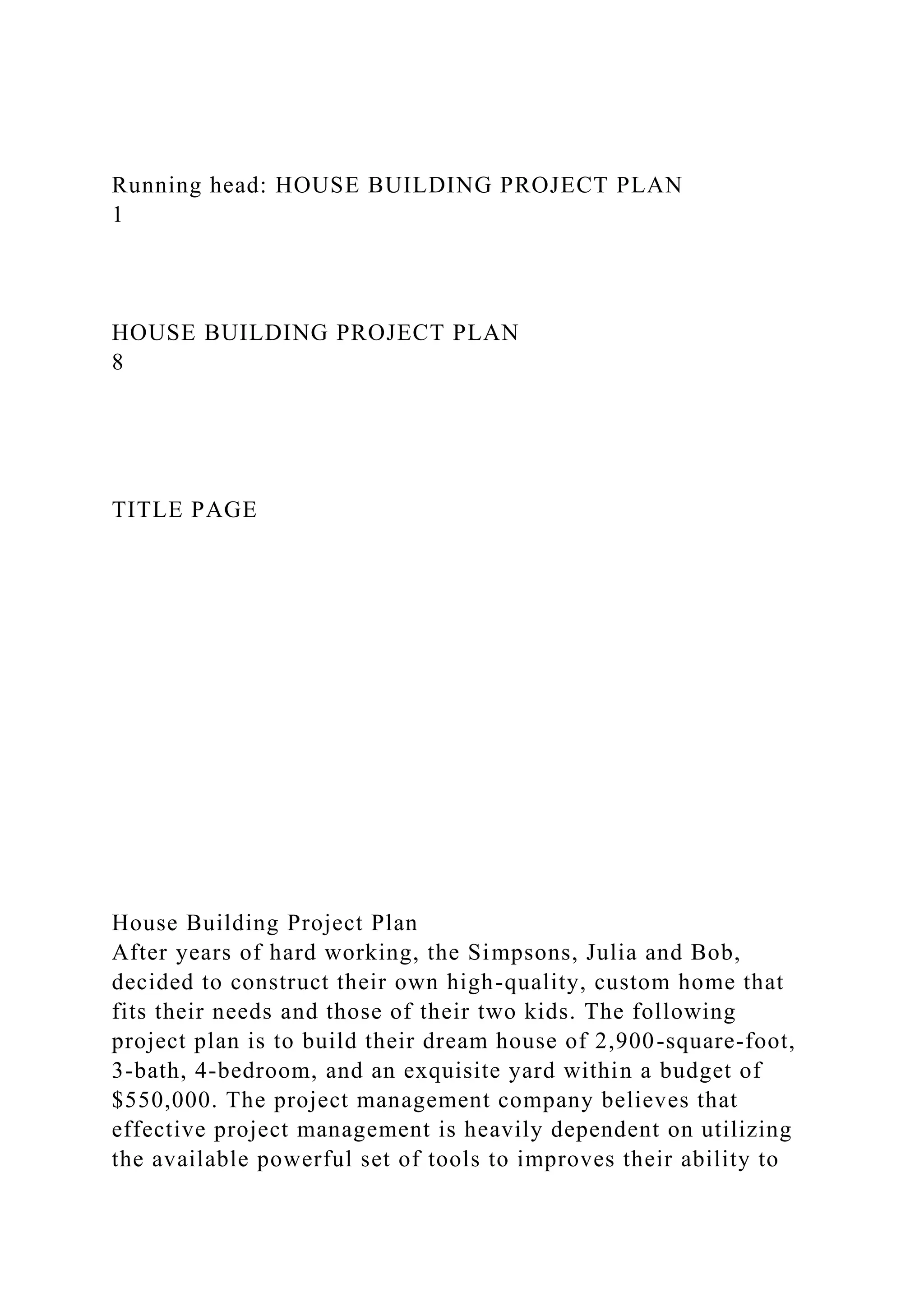

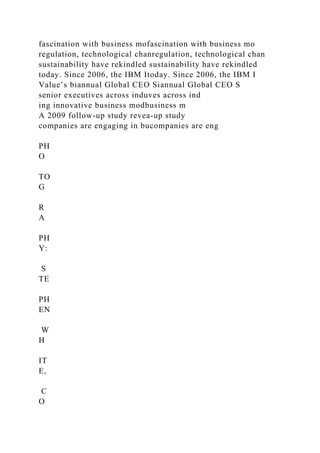

![majority of its product portfolio in col-

laboration with a few designers or to engage with a broad range

of creative resources. Table 2 shows

that innovators’ Balanced Breadth is significantly higher than

that of imitators (0.457 vs 0.313).

Besides Osmosis and Balanced Breadth, the relationship

between knowledge diversity of creative

collaborators and company innovation is analysed in terms of

Foreign Background, Educational

Background, Subsector Brokering and Industry Brokering (see

Table 2). Innovators tend to develop

about half of their product portfolio in collaboration with

foreign designers (45.7 per cent), while

imitators show significantly lower values (16 per cent) for the

Foreign Background metric. The

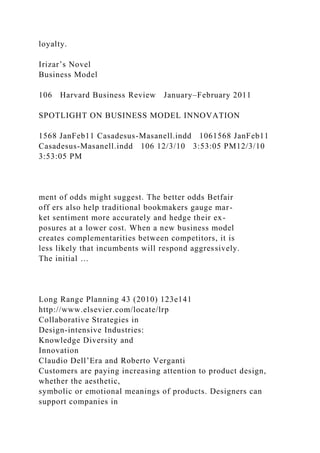

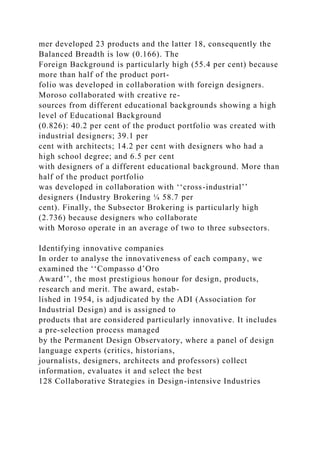

empirical results show a curvilinear relationship between

innovation and the percentage of products

developed in collaboration with foreign designers. The bubble

plot for Foreign Background in

Figure 3 shows an inverted U-shaped curve: 42.6 per cent of

innovators belong to the central set

Figure 3. Foreign Background e Innovators vs Imitators [radius

is proportional to the number of

companies]

130 Collaborative Strategies in Design-intensive Industries

(40-60 per cent). Knowledge exchange driven by creative

resources from different countries allows

innovators to access new semantic contexts and to propose

innovations in product sign and mean-

ing. Innovators collaborate with designers from 5.3 different

nations, whereas imitators have a cor-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadhousebuildingprojectplan-230125022624-d4343c3d/85/Running-head-HOUSE-BUILDING-PROJECT-PLAN-docx-49-320.jpg)

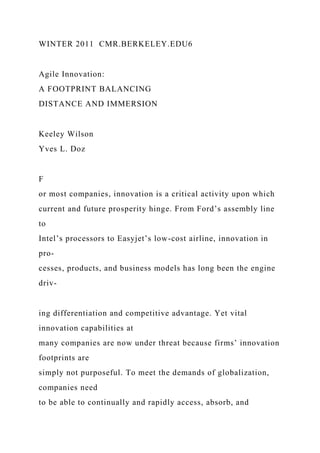

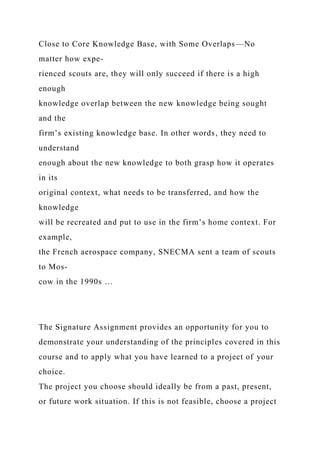

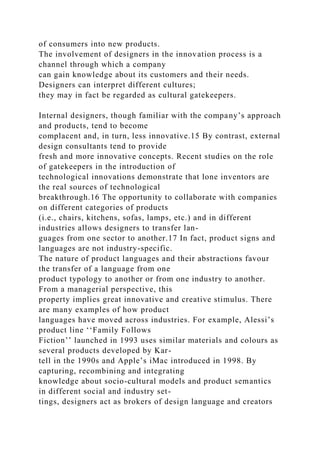

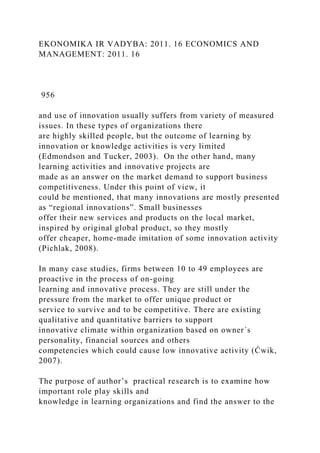

![statistically significant. Figure 5 shows a bubble

plot obtained by grouping the companies into five sets

according to their Industry Brokering values:

(0-20 per cent), (20-40), (40-60), (60-80) and (80-100).

Similarly to Foreign Background also

Industry Brokering shows an inverted U-shaped: innovators are

concentrated in a central set d 47.6

per cent of innovators belongs to the (60-80) group. Few

innovative companies, such as Driade,

Flos and FontanaArte develop more than 80 per cent of their

products in collaboration with

designers who operate across several industries. At the same

time, other innovators, such as B&B

Italia, Foscarini and Luceplan, show values lower than 40 per

cent. Future research could

explore this further by analysing whether specific industries can

significantly …

ISSN 1822-6515 ISSN 1822-6515

EKONOMIKA IR VADYBA: 2011. 16 ECONOMICS AND

MANAGEMENT: 2011. 16

954

COMPETENCIES AND INNOVATION WITHIN LEARNING

ORGANIZATION

Jarmila Šebestová1, Žaneta Rylková2

1Silesian University, Karvina, Czech Republic,

[email protected]

2Silesian University, Karvina, Czech Republic,

[email protected]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadhousebuildingprojectplan-230125022624-d4343c3d/85/Running-head-HOUSE-BUILDING-PROJECT-PLAN-docx-51-320.jpg)

![aimed at adding value to the knowledge

acquired and communicated throughout the firm. As such,

organizational learning processes encompass the

acceptance and the assimilation of knowledge. We can say that

organizational learning is the process that

should lead to the building of firm´s competencies and that a

valuable learning experience will lead to firm-

specific, distinctive competencies.

Organizational learning is a strategic process and a learning

organization is the output of this process

that will allow the development of new or regenerated core

competencies and products. Many studies of

learning organizations have attempted to diagnose the

characteristics of learning organization. Although

different authors stress different elements, the characteristics of

the learning organization incorporated in this

study have been proposed important features: open

communications, risk taking, support and recognition for

mailto:[email protected]

ISSN 1822-6515 ISSN 1822-6515

EKONOMIKA IR VADYBA: 2011. 16 ECONOMICS AND

MANAGEMENT: 2011. 16

955

learning, resources to perform the job, teams, rewards for

learning, training and learning environment,

knowledge management.

Innovation and Learning](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadhousebuildingprojectplan-230125022624-d4343c3d/85/Running-head-HOUSE-BUILDING-PROJECT-PLAN-docx-54-320.jpg)

![Their economical and business importance predestines

developmental tendency and performance growth in

economics of states and companies. In management of

innovation there is purposeful to understand under

innovation a creative human activity, which developed positive

change in structure of entrepreneurial

subjects and which has results in required and expected positive

effect.

Conclusion

The challenge facing managers today is to make the effort

needed to learn some of the new skills and

techniques, and to put in processes that engage their workforce

in programmes of continuous capability

development. Learning should be integrated into the doing, as

part and parcel of everyday work. It should

also be energising, stimulating and fun. Getting the best out of

everybody, including yourself to meet the

challenges ahead. In today´s conditions of uncertainty and rapid

change, many organizations need to reassess

focus and direction quickly, rethink how people work together

and learn for innovation.

References

1. Burke, W. W., Litwin, G. H.: A causal model of

organizational performance and change. “Journal of

Management”,1992, vol.18, pp. 523–545.

2. Ćwik, K.: Elastyczność i innowacyjność a zachowania

strategiczne przedsiębiorstw, „Zarządzanie” No. 5 Prace

Naukowe Akademii Ekonomicznej We Wrocławiu Wydawnictwo

Akademii Ekonomicznej im. Oskara Langego

we Wrocławiu Wrocław 2007 [in Polish].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadhousebuildingprojectplan-230125022624-d4343c3d/85/Running-head-HOUSE-BUILDING-PROJECT-PLAN-docx-67-320.jpg)

![3. Damanpour, F.: Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis

of effects of determinants and moderators. “Academy

of Management Journal”, 1991 vol.34, pp.555–590.

4. Edmondson, A. C., Tucker, A. L.: Why hospitals don't learn

from failures: organizational and psychological

dynamics that inhibit system change. “California Management

Review”, 2003 Vol. 45, No. 2. p. 55-72.

5. Henderson R. M., Clark K.C.: Architectural Innovation: the

Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and

the Failure of Established Frims. [in:] Administrative Science

Quarterly, 35.

6. Hurley, R. F., Hult G. T.: Innovation, Market Orientation,

and Organizational Learning: an Integration and

Empirical Examination. [in:] Journal of Marketing, 62.

7. Ilangovan, A., Scroggins, W.A. Rozell, E.J. Managerial

Perspectives on Emotional Intelligence Differences

Between India and the United States: The Development of

Research Propositions. “International journal of

Management” 24/3 , 2007 541-549

8. Kimberly, J.,Cook, J. M. Organizational Measurement and

the Implementation of Innovations in Mental Health

Services. “Administration and Policy in Mental Health and

Mental Health Services Research” ,2008, vol. 35,

pp.11-20.

9. Lehman, W. E. K., Greener, J. M., Simpson, D. : Assessing

organizational readiness for change. “Journal of

Substance Abuse Treatment”, 2002, pp.197–209.

10. McDaniel, R.R., Driebe, D. J. : Complexity Science and

Health Care Management. [in:] John D. Blair, Myron D.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadhousebuildingprojectplan-230125022624-d4343c3d/85/Running-head-HOUSE-BUILDING-PROJECT-PLAN-docx-68-320.jpg)

![Fottler and Grant T. Savage, (Eds.) Advances in Health Care

Management, Stamford, CN: JAI Press, 2001, volume

2, pp. 11-36.

11. Pawliczek, A. : Podnikání ve výzkumu a vývoji, inovace a

start-up (spin-off). Distanční studijní opora ke kurzu v

projektu ESF CZ.04.1.03/3.215.1/0103. 87 s. Ostrava, 2006 [in

Czech].

12. Pedler M., Boydell T., Burgoyne P.: Towards the Learning

Company, [in:] Management Education and

Development, Vol.20, No.1, 1989.

13. Pichlak, M.: Finansowe aspekty innowacyjności

przedsiębiorstw w województwie śląskim. „Organizacja i

Zarządzanie”. Kwartalnik Naukowy nr. 2/2008. 5-16 [in Polish].

14. Senge P. M.: The Fifth Discipline: the Art of Organizational

Learning Systems. Currence Doubleday, 1990. ISBN

0-385-26095-4.

15. Serrat, O.: Dimensions of the Learning Organization, 2009

[in:]

http://www.adb.org/Documents/Information/Knowledge-

Solution

s/Dimensions-Learning-Organization.pdf.

16. Sharma, S.: Applied Multivariate Techniques. New York:

John Wiley & Sons, 1996.

17. Tichá I.: Učící se organizace, Alfa Publishing, 2005. ISBN](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadhousebuildingprojectplan-230125022624-d4343c3d/85/Running-head-HOUSE-BUILDING-PROJECT-PLAN-docx-69-320.jpg)

![80-86851-19-2. [in Czech].

18. Vlček R.: Hodnota pro zákazníka, Management Press, 2002.

ISBN 80-7261-068-6. [in Czech].

19. Zapletalová, Š. : The Influence of Globalization Process on

the Business Management of Entrepreneurial Subjects

in Central and Eastern Europe. “Current Issues of Business and

Law”, 2008. pp. 167-173.

Copyright of Economics & Management is the property of

Kaunas University of Technology, Faculty of

Economics & Management and its content may not be copied or

emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv

without the copyright holder's express written permission.

However, users may print, download, or email

articles for individual use.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadhousebuildingprojectplan-230125022624-d4343c3d/85/Running-head-HOUSE-BUILDING-PROJECT-PLAN-docx-70-320.jpg)