This document critiques four research articles on note-taking methodologies, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses in understanding the effects of note-taking on learning. The evaluations reveal issues such as the impact of using laptops versus longhand notes on cognitive processing, the validity of measurement methods, and the importance of balancing internal and external validity in research. The critique suggests that future studies should consider varied note-taking methods and environments to enhance our understanding of the learning process.

![touts the benefits of the ability to review material (even

from notes taken by someone else). These two theories

are not incompatible; students who both take and review

524581PSSXXX10.1177/0956797614524581Mueller,

OppenheimerLonghand and Laptop Note Taking

research-article2014

Corresponding Author:

Pam A. Mueller, Princeton University, Psychology Department,

Princeton, NJ 08544

E-mail: [email protected]

The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard:

Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop

Note Taking

Pam A. Mueller1 and Daniel M. Oppenheimer2

1Princeton University and 2University of California, Los

Angeles

Abstract

Taking notes on laptops rather than in longhand is increasingly

common. Many researchers have suggested that laptop

note taking is less effective than longhand note taking for

learning. Prior studies have primarily focused on students’

capacity for multitasking and distraction when using laptops.

The present research suggests that even when laptops

are used solely to take notes, they may still be impairing

learning because their use results in shallower processing.

In three studies, we found that students who took notes on

laptops performed worse on conceptual questions than

students who took notes longhand. We show that whereas taking

more notes can be beneficial, laptop note takers’

tendency to transcribe lectures verbatim rather than processing

information and reframing it in their own words is

detrimental to learning.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-8-320.jpg)

![chunk of text in the lecture transcript, and reported

a percentage of matches for each. Using three-word

chunks (3-grams) as the measure, we found that laptop

notes contained an average of 14.6% verbatim overlap

with the lecture (SD = 7.3%), whereas longhand notes

averaged only 8.8% (SD = 4.8%), t(63) = −3.77, p < .001,

d = 0.94 (see Fig. 3); 2-grams and 1-grams also showed

significant differences in the same direction.

Overall, participants who took more notes performed

better, β = 0.34, p = .023, partial R2 = .08. However, those

whose notes had less verbatim overlap with the lecture

also performed better, β = −0.43, p = .005, partial R2 = .12.

We tested a model using word count and verbatim over-

lap as mediators of the relationship between note-taking

medium and performance using Preacher and Hayes’s

(2004) bootstrapping procedure. The indirect effect is

significant if its 95% confidence intervals do not include

zero. The full model with note-taking medium as the

independent variable and both word count and verbatim

overlap as mediators was a significant predictor of per-

formance, F(3, 61) = 4.25, p = .009, R2 = .17. In the full

model, the direct effect of note-taking medium remained

a marginally significant predictor, b = 0.54 (β = 0.27),

p = .07, partial R2 = .05; both indirect effects were signifi-

cant. Longhand note taking negatively predicted word

count, and word count positively predicted performance,

indirect effect = −0.57, 95% confidence interval (CI) =

[−1.03, −0.20]. Longhand note taking also negatively pre-

dicted verbatim overlap, and verbatim overlap negatively

predicted performance, indirect effect = 0.34, 95% CI =

[0.14, 0.71]. Normal theory tests provided identical

conclusions.7

–0.4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-14-320.jpg)

![59.6) than those who took laptop notes without receiving

an intervention (M = 260.9, SD = 118.5), t(97) = −5.51,

p < .001, d = 1.11 (see Fig. 2), as well as less than those

who took laptop notes after the verbal intervention (M =

229.02, SD = 84.8), t(98) = −4.94, p < .001, d = 1.00. Long-

hand participants also had significantly less verbatim

overlap (M = 6.9%, SD = 4.2%) than laptop-noninterven-

tion participants (M = 12.11%, SD = 5.0%), t(97) = −5.58,

p < .001, d = 1.12 (see Fig. 3), or laptop-intervention

participants (M = 12.07%, SD = 6.0%), t(98) = −4.96, p <

.001, d = 0.99. The instruction to not take verbatim notes

was completely ineffective at reducing verbatim content

(p = .97).

Comparing longhand and laptop-nonintervention note

taking, we found that for conceptual questions, partici-

pants taking more notes performed better, β = 0.27, p =

.02, partial R2 = .05, but those whose notes had less ver-

batim overlap also performed better, β = −0.30, p = .01,

partial R2 = .06, which replicates the findings of Study 1.

We tested a model using word count and verbatim over-

lap as mediators of the relationship between note-taking

medium and performance; it was a good fit, F(3, 95) =

5.23, p = .002, R2 = .14. Again, both indirect effects were

significant: Longhand note taking negatively predicted

word count, and word count positively predicted perfor-

mance, indirect effect = −0.34, 95% CI = [−0.56, −0.14].

Longhand note taking also negatively predicted verbatim

overlap, and verbatim overlap negatively predicted per-

formance, indirect effect = 0.19, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.49]. The

direct effect of note-taking medium remained significant,

b = 0.58 (β = 0.30), p = .01, partial R2 = .06, so there is

likely more at play than the two opposing mechanisms

we identified here. When laptop (with intervention) was

included as an intermediate condition, the pattern of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-22-320.jpg)

![effects remained the same, though the magnitude

decreased; indirect effect of word count = −0.18, 95%

CI = [−0.29, −0.08], indirect effect of verbatim overlap =

0.08, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.17].

The intervention did not improve memory perfor-

mance above that for the laptop-nonintervention condi-

tion, but it was also not statistically distinguishable from

memory in the longhand condition. However, the inter-

vention was completely ineffective at reducing verbatim

content, and the overall relationship between verbatim

content and negative performance held. Thus, whereas

the effect of the intervention on performance is ambigu-

ous, any potential impact is unrelated to the mechanisms

explored in this article.

Study 3

Whereas laptop users may not be encoding as much

information while taking notes as longhand writers are,

they record significantly more content. It is possible that

–0.4

–0.3

–0.2

–0.1

0

0.1

0.2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-23-320.jpg)

![ticipants (z-score Ms = −0.14, 0.04, −0.05), t(105) = 1.82,

p = .07, d = 0.4 (for raw means, see Table 2).

Content analysis of notes. Again, longhand note tak-

ers wrote significantly fewer words (M = 390.65, SD =

143.89) than those who typed (M = 548.73, SD = 252.68),

t(107) = 4.00, p < .001, d = 0.77 (see Fig. 2). As in the pre-

vious studies, there was a significant difference in verba-

tim overlap, with a mean of 11.6% overlap (SD = 5.7%) for

laptop note taking and only 4.2% (SD = 2.5%) for long-

hand, t(107) = 8.80, p < .001, d = 1.68 (see Fig. 3). There

were no significant differences in word count or verbatim

overlap between the study and no-study conditions.

The amount of notes taken positively predicted perfor-

mance for all participants, β = 0.35, p < .001, R2 = .12. The

extent of verbatim overlap did not significantly predict

performance for participants who did not study their

notes, β = 0.13. However, for participants who studied

their notes (and thus those who were most likely to be

affected by the contents), verbatim overlap negatively pre-

dicted overall performance, β = −0.27, p = .046, R2 = .07.

When looking at overall test performance, longhand note

taking negatively predicted word count, which positively

predicted performance, indirect effect = −0.15, 95% CI =

[−0.24, −0.08]. Longhand note taking also negatively pre-

dicted verbatim overlap, which negatively predicted per-

formance, indirect effect = 0.096, 95% CI = [0.004, 0.23].

However, a more nuanced story can be told; the indi-

rect effects differ for conceptual and factual questions.

For conceptual questions, there were significant indirect

effects on performance via both word count (−0.17, 95%

CI = [−0.29, −0.08]) and verbatim overlap (0.13, 95% CI =

[0.02, 0.15]). The indirect effect of word count for factual](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-29-320.jpg)

![questions was similar (−0.11, 95% CI = [−0.21, −0.06]), but

there was no significant indirect effect of verbatim overlap

(0.04, 95% CI = [−0.07, 0.16]). Indeed, for factual ques-

tions, there was no significant direct effect of overlap on

–0.3

–0.2

–0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

Combined Factual Conceptual

Pe

rf

or

m

an

ce

(z

s](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-30-320.jpg)

![verbal working memory (VWM); select, construct, and/or trans-

form important thematic units before the information in working

memory is forgotten; quickly transcribe (via writing or typing)

the

information held in working memory, again before the

information

is forgotten; and maintain the continuity of the lecture (which

also

1 Working memory is defined by most as storage and processing

(e.g.,

Baddeley, 2001). There are a least four different categories of

working

memory theories, and each proposes a different explanation for

individual

differences in working memory. See Miyake and Shah (1999)

and Peverly

(2006) as well as the General Discussion of this article.

Stephen T. Peverly, Vivek Ramaswamy, Cindy Brown, James

Sumowski, and Moona Alidoost, Teachers College, Columbia

University;

Joanna Garner, who is now at the Department of Applied

Psychology, The

Pennsylvania State University—Berks.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to

Stephen

T. Peverly, Teachers College, Columbia University, Box 120,

525 West

120th Street, New York, NY 10027. E-mail: [email protected]

Journal of Educational Psychology Copyright 2007 by the

American Psychological Association

2007, Vol. 99, No. 1, 167–180 0022-0663/07/$12.00 DOI:

10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.167](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-46-320.jpg)

![given the lack of consensus among researchers about what such

tasks actually measure (Daneman, 2001). Also, future research

should measure note takers’ selective attention, as Engle (2002)

argued that capacity is related to the “ability to control attention

[and avoid distraction] to maintain information in an active,

quickly retrievable state” (p. 20). It may be the ability to attend,

not

the capacity of VWM, that partially accounts for skill in taking

notes. Finally, the main idea task (pilot study) did not

contribute to

the skill of note taking. Logically, some variable must be

related to

the ability to identify and construct important information

during a

lecture. Future researchers may want to use a listening rather

than

a reading comprehension task. Although both measure the same

higher level cognitive processes (Kintsch, 1998), the former is

not

confounded by differences in word recognition speed.

Table 8

Study 1: Summary of the Structural Equation Model

Structural path Estimate SE CR

Comp. flu 3 notes .09 .15 0.95

Sem. flu 3 notes �.14 .09 �1.36

VWM 3 notes �.06 .51 �0.76

Let. flu 3 notes .29 .05 2.96**

Phon. flu 3 notes .09 .09 1.04

Notes 3 essay .51 .04 7.12****

Note. CR � critical ratio; Comp. � composition; flu � fluency;

Sem. �](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-96-320.jpg)

![a Indicates separate content areas.

Received July 15, 2005

Revision received June 29, 2006

Accepted July 6, 2006 �

180 PEVERLY ET AL.

Computers in Human Behavior 34 (2014) 148–156

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Computers in Human Behavior

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c

a t e / c o m p h u m b e h

Research Report

An experimental study of online chatting and notetaking

techniques

on college students’ cognitive learning from a lecture

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.019

0747-5632/� 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

⇑ Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 9012991212.

E-mail address: [email protected] (F.-Y.F. Wei).

Fang-Yi Flora Wei ⇑ , Y. Ken Wang, Warren Fass

University of Pittsburgh, 300 Campus Drive, Bradford, PA

16701, United States

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Available online 22 February 2014](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-114-320.jpg)

![era of multitasking can balance Internet use and classroom

partic-

ipation’’ (Young, 2006, p. A27), and they believe that

multitasking

http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1016/j.chb.2014.01

.019&domain=pdf

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.019

mailto:[email protected]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.019

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/07475632

http://www.elsevier.com/locate/comphumbeh

F.-Y.F. Wei et al. / Computers in Human Behavior 34 (2014)

148–156 149

online activities do not negatively influence their notetaking

behavior, nor retention of lecture material.

Because off-learning multitasking behavior potentially can

interrupt students’ sustained attention and weaken their

cognitive

learning during class (Wei, Wang, & Klausner, 2012), the main

con-

cern is whether off-learning multitasking behavior (see Lindroth

&

Bergquist, 2010), such as chatting online during classroom

note-

taking, can interfere with the learning task and jeopardize

students’ learning outcomes.

To address this important issue, this experimental study inves-

tigated whether computer-mediated notetaking influences stu-

dents’ cognitive learning with respect to two dimensions. First,

we compared the effect of no notetaking, handwritten

notetaking,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-118-320.jpg)

![conceptualisation of the process, that

this would lead to a more heterogeneous view of taking notes in

lectures and that there may

be a case for more integration of EAP into mainstream courses.

# 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd.

All rights reserved.

Keywords: Taking notes in lectures; Student views; Study

skills; EAP

System 29 (2001) 405–417

www.elsevier.com/locate/system

0346-251X/01/$ - see front matter # 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd.

All rights reserved.

PII: S0346-251X(01)00028-8

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +44-1786-466-130; fax: +44-

1786-463-398.

E-mail address: [email protected] (R. Badger).

1. Introduction

Students at tertiary institutions come from a variety of academic

backgrounds.

This means some students are less well prepared than others for

study in a university

setting and raises the question of the extent to which

universities should help stu-

dents with study skills, such as the focus of this paper, taking](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-167-320.jpg)

![students were admitted to undergraduate

programmes in the UK. We know of only one student who

dropped out after a semester.

Table 3

Units taken by subjecta

Cohort Subject areas taken

Traditional Education(6), Sociology(4), Philosophy(2),

Business(2), French

Access Arts and Human Sciences

International EAP (6), Education(4), description of English(3),

Japanese(2), Business (2), French(1),

a Students on undergraduate degree programmes take up to

three units per semester.

R. Badger / System 29 (2001) 405–417 409

To help with writing essays (traditional).

You need [notes] to get the points they want you to bring out in

exams or essays

(access).

It helps with exams (international).

One access student thought that notes were not useful in this

way.

I don’t really think they [notes] help you with exams or essays.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-176-320.jpg)

![For exams you

have books to read.

More general educational reasons (two responses)

Something that makes my brain think.

To educate myself.

This kind of reason was given only by two students, both

access.

Process (three responses)

You have to concentrate (traditional).

If you were sitting in a lecture and just listening to somebody

talking for an hour

you can easily drift off (traditional).

If the lecture is boring I take notes (access).

One international student, like some of Dunkel and Davy’s

(1989) subjects, put

forward a kind of negative process reason.

I have to concentrate on understanding what he [the lecturer]

says. I don’t have

time to take notes (international).

Again one traditional student said that she took notes out of fear

of forgetting.

I think if I took that element of fear out of it then I would

remember more.

4.3. During the lecture: the content of the notes

There was considerable variation, both between individual

students and groups of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-177-320.jpg)

![Information presented in slides or transparencies is unlikely to

be recorded in

students’ notebooks.

Our reading of this is that the use of the overhead projector and

PowerPoint is

consistentwith transmissionviewsof learningwhere

lecturesareprimarilymonologues.

All the students who said that they exclude their own opinions

cited the use of OHPs

orPowerPointasa signalof importance.Someexamplesof

studentcomments follow:

Everythingyouneedtowritedownisuponthescreenandbasicallyyou

copydown

exactly what’s there. Nothing from the words the lecturer is

saying (traditional).

In the [. . .] department everything is done on computer. I think

if it’s done that

way it feels as if you have to take notes (traditional).

I try to copy them [OHPs] down if they are hand written

(access).

Iwill copydownthingsontheOHPbecause it’san importantpoint

(international).

Again this is evidence of students seeing their role as recipients

of knowledge. What

is interesting here, though, is that some students seem to be

aware that the use of

techniques such as PowerPoint reinforce a transmission model

of learning. Whatever

is thought of this model of learning, it would appear that

students are responding

intelligently to a particular kind of context.

None of our subjects mentioned discourse markers at this stage

in the interview](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-180-320.jpg)

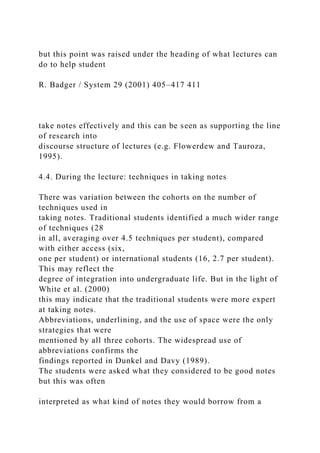

![4.7. Help

Traditional studentswere themost forthcomingaboutwhathelp

couldbeprovided

but varied widely in what they thought would make note-taking

in lectures easier.

The most significant factors were greater use of hand-outs (four

traditional students)

and,asnotedabove, indicating that something is important

(twotraditional students).

You can take the information [on handouts] away and read it in

your own time.

By the tone of their voice [lecturers] indicate what’s important.

But one student said:

The last time I got a handout I just binned it.

Other factors mentioned included some contradictory views on

movement:

Table 4

Techniques used in note taking

Ta Ib Ac Total

Abbreviations 3 5 1 9

Numbering 1 2 0 3

Asterixes 3 1 0 4

Underlining 4 2 1 7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-184-320.jpg)

![Visual aids were also cited:

I find it [PowerPoint] very useful (traditional).

Some lecturers . . . put something on the overhead and they

whip it off just as

you are about to write it down and that is one of the most

annoying things

(traditional).

This supports Habeshaw’s (1995) advice to lecturers to use

visual aids more often

and more effectively.

One student also mentioned the degree of interactivity.

I think that what would be helpful . . . almost make it an option

to be inter-

active. You know if I say something that you don’t understand,

then question

me (traditional).

This fits in well with Gibbs’ (1992) suggestions for structured

lectures which

include group discussion.

There was generally a rather negative response to the possibility

of a course in

note-taking from lectures with four traditional students saying

they would not have

attended such a course.

Iknowthereare learningstrategycoursesbutmyneedsaredifferent

(traditional).

I don’t think I would have gone to anything on it [note-taking]

(traditional).

I think if you’re older you’ve got the experience of what you](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadcriticalevaluationonnotetaking1criticalev-230123065034-baf7ae7d/85/Running-Head-Critical-Evaluation-on-Note-Taking1Critical-Ev-docx-186-320.jpg)