The document explores the postwar period and neocolonialism in the Philippines, detailing the nation's political, economic, and military conditions and its dependence on the United States despite gaining independence in 1946. It emphasizes the influence of the U.S. on Philippine governance, the rise of the Huk rebellion, and CIA reports reflecting concerns about the resistance movement and government instability. The lesson incorporates primary sources to analyze the complexities of Philippine-American relations and the implications for democracy and sovereignty during the Cold War era.

![who constitute the Filipino ruling clique" and "resulting from a lack of civil

spirit, from knowledge of economic power, and from confidence in the past

apathy of the disorganized and uneducated mass of the people."

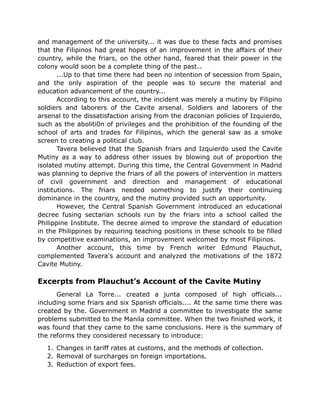

In terms of the Philippine economy at that period, the CIA described

the Philippines as "almost self-sufficient in food [which] favors long-range

stability." However, they also mentioned how "long-standing inequalities in

the nation 's agrarian system... have been exploited by the Communist and

have not only facilitated the development of the Huk movement in Luzon

but are producing unrest elsewhere in the archipelago." The CIA also

mentioned the critical problem of the "nation's rapidly deteriorating financial

position." The Philippine government dealt with this problem by increasing

taxes and tightening import control. These measures resulted in price

increases in imported goods. The government also encountered difficulties

in the conduct of foreign trade, which further led to "increased popular

doubt as to the country's economic future, which led to aggravated political

instability."

Aside from the corruption and inefficiency of the government, which

the CIA saw as a result of "political immaturity and inadequate education,"

the law enforcement institutions of the Philippine Constabulary and the

Philippine Armed Forces were also seen to not possess any "capability for

maintaining law and order or even for preventing destructive raids by the

Huks." The Huks, which was the central concern of the United States, was

an organization that: ought the Japanese in the preceding war period and

became an anti-government group during the postwar years. In this 1950

document, the CIA estimated that "although Huk activity is presently

confined in the island of Luzon, it is expanding and growing the 1950

estimate of the CIA on Huk membership was pegged at 15,000 with the

prospect of further increase. The CIA believed that the Huks were equipped

with weapons that were sufficient and appropriate for their guerrilla

operations. These weapons were acquired through theft, purchase, and

seizure from government forces, the guerrillas were also sustained with the

food and clothing "willingly contributed by sympathetic peasants and

villagers." At times, the Huks also resort to force or intimidation in acquiring

these essential supplies.

The CIA assessed that the Huks were of high morals as evident on the "very

few Huks [who] have taken advantage of past Government amnesty offers."

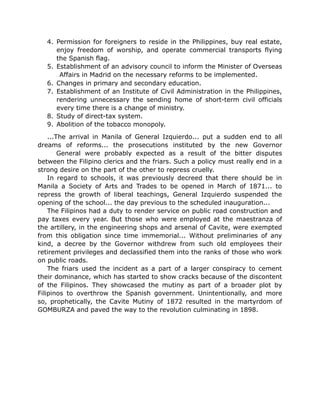

On the other hand, the CIA's appraisal Of the Philippine Armed Forces and

Constabulary was pessimistic. While the government forces were "well-

equipped in comparison with their opponents" with U.S.-sourced materials,

the combat efficiency of both the Army and the Constabulary lacked](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rphchapter2-lesson9chapter3-lesson10-12-240827044758-79a47c70/85/RPH_-CHAPTER-2-lesson-9_CHAPTER-3-LESSON-10-12-docx-4-320.jpg)

![coordination and suffered from the failure in relieving small units in the

field. While the deteriorating political stability of the period had little to no

effect on the loyalty of the uniformed personnel, their morale was generally

low. The CIA concluded that more intensive." the "[u]nit leadership is not of

high quality, and an aggressive spirit is lacking in all ranks. The

ineffectiveness of government forces is in part attributable to difficult terrain

and local sympathy for the Huks."

Analysis of the CIA Memorandum

It is essential to have contextual knowledge of the 1950 period to

appreciate the report summarized on the previous pages. As mentioned, the

period that immediately followed World War Il was dictated by the Cold War.

In this period, the two strongest and most powerful nation-states in the

world were vying for world supremacy and were engaging in a diplomatic

contest. Both the United States and the USSR were suspecting each other of

an agenda to dominate the world.

Both countries engaged in a race of accumulation of arms, territories,

and wealth to secure their place in the current world order. The fundamental

difference between them would be their respective state ideologies. On the

one hand, the United States was committed to liberal democracy and a

liberal capitalist political economy. These ideas, after all, launched the

relatively young nation to world greatness in a matter of decades. On the

other hand, the USSR was as committed to their socialist and communist

ideology and the intent to export the glorious Russian Communist

Revolution of 1917 across the world.

In this scenario, the United States, erstwhile colonial master and ally

of the nascent Philippine Republic, was positioning in the Pacific. The

Philippines, as its territory since 1899, was an essential stronghold as the

Chinese Communist Party's revolution succeeded in 1949. The United States

wanted to contain communism in the Pacific and Southeast Asia. That was

why the presence of a growing communist army, the Huks, was a U.S.

concern.

This concern was apparent in this August 1950 memo. The report,

while presenting a general picture of the Philippines, was centrally

concerned with the current situation of the Huk rebellion in the country. For

example, in characterizing the political situation in the country, the report

ultimately tied back on the effects of instability and the increasing

discontent of the people against the government to the communist

movement. They were apprehensive about how the decline in the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rphchapter2-lesson9chapter3-lesson10-12-240827044758-79a47c70/85/RPH_-CHAPTER-2-lesson-9_CHAPTER-3-LESSON-10-12-docx-5-320.jpg)

![Leon O. Ty's "It's Up to You Now" and the Magsaysay Myth

Mainstream Philippine history textbooks always paint Ramon

Magsaysay as the People's President. His humble beginnings and

educational background were placed in stark contrast to his predecessors'.

Indeed, the presidents before him were all lawyers who came from the old,

landed elite families and were prominent figures in Philippine politics for

many generations of the American period. Magsaysay, however, did not

enjoy the same advantages. He was not a lawyer, did not come from the

national elite, was former employee of a bus company in his province, and a

hardened guerrilla during the war. He was a governor of Zambales, elected

as a legislator, and was appointed as secretary of National Defense under

President Quirino. As defense secretary, Magsaysay gained popularity in his

successful campaign against the Huks.

For all intents and purposes, Magsaysay was painted as a self-made

president who rose from the ranks of the masses through sheer ability and

patriotism. He was celebrated as an anti-communist hero who broke the

growing momentum of the Huk rebellion as a defense secretary. He was

beholden to no one because he had no significant business interest and was

perceived and portrayed as a "man of action" who would put an end to the

corruption and inefficiency of the government led by an oligarchy. U.S.

newspapers and magazines supported this image, and so did the Philippine

press.

Journalist Leon O. Ty penned an article "It's Up to You Now" for the

Philippine Free Press three days before the November 1953 presidential

election. This article is an illustration of Magsaysay's portrayal in the press.

The article started with an anecdote where defense secretary Magsaysay

called a newsman to express his worries in the way things were run in the

Quirino cabinet' The article narrated how Magsaysay worried about having

earned the ire of the president when he contradicted a particular shady deal

about sugar importation that involved a certain compadre to the president.

The article read:

I have my doubts,' Magsaysay answered rather gloomily. 'The APO

[pertaining to the president] seems to dislike me now.'

'But why should he dislike you?' the newsman queried. 'Didn't you restore

peace and order for him? You gave him prestige when you kept the 1951

elections clean. The President has repeatedly said he is proud of you.'](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rphchapter2-lesson9chapter3-lesson10-12-240827044758-79a47c70/85/RPH_-CHAPTER-2-lesson-9_CHAPTER-3-LESSON-10-12-docx-8-320.jpg)

![McCoy, A. (2009). Policing America 's Empire: The United States, the

Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State. Madison: University of

Wisconsin Press.

Shalom, S. R. (1981). The United States and the Philippines: A Study of

Neocolonialism. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Simbulan, R. (2000). The CIA in Manila: Covert operationS and the CIA's

Hidden History in the Philippines. Manila Studies Program Paper #14.

University of the Philippines Manila.

Ty, L. O. (1953). It's Up to You Now! Philippine Free press. Retrieved 4

February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHi1

Batas Militar. (Documentary). Retrieved 4 February 2021 from:

http://bit.y/RdgsPHi2 PODKAS. (2021). Corazon Aquino's speech in the US

congress. [Podcast]. Retrieved 4 February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHi3

PODKAS. (2021). Leon Ty's It's Up To You Now. [Podcast]. Retrieved 4

February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHi4

U.S. Central Intelligence Library. Retrieved 4 February 2021 from:

https://www.cia. gov/library/readingroom/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rphchapter2-lesson9chapter3-lesson10-12-240827044758-79a47c70/85/RPH_-CHAPTER-2-lesson-9_CHAPTER-3-LESSON-10-12-docx-18-320.jpg)

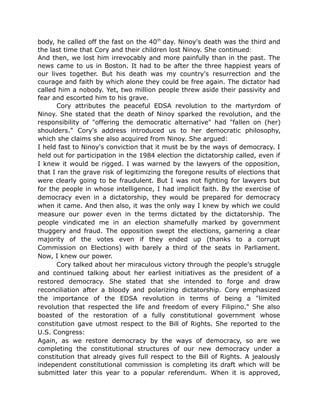

![Most Illustrious Sir, the agent of the Cuerpo de Vigilancia stationed in

Fort Santiago to report on the events during the (illegible) day in prison of

the Jose Rizal, informs me on this date of the following:

At 7:50 yesterday morning, Jose Rizal entered death row

accompanied by his counsel. Senor Taviel de Andrade, and the Jesuit priest

[Josel Vilaclara. At the urgings of the former and moments after entering, he

was served a light brvakfast. At approximately 9, the Adjutant of the

Garrison, Senor [Eloyl Maure, asked Rizal if he wanted anything. He tvplied

that at the moment he only wanted a prayer book which was brought to him

shortly by Father [Estanislao] March.

Señor Andrade left death row at 10 and Rizal spoke for a long while

with the Jesuit fathers, March and Vilaclara, regarding religious matters, it

seems. It appears that these two presented him with a prepared retraction

on his life and deeds that he refused to sign. They argued about the matter

until 12:30 when Rizal ate some poached egg and a little chicken.

Afterwards he asked to leave to write and wrote for a long time by himself.

At 3 in the afternoon, Father March entered the chapel and Rizal

handed him what he had written. Immediately the chief of the firing squad,

Señor [Juan] del Fresno and the Assistant of the Plaza, Senor Maure, were

informed. They entered death row and together with Rizal signed the

document that the accused had written. It seems this was the retraction.

From 3 to 5:30 in the afternoon, Rizal read his prayer book several

times, prayed kneeling before the altar and in the company of Fathers

Vilaclara and March, read the Acts of Faith, Hope and Charity repeatedly as

well as the Prayers for the Departing Soul.

At 6 in the afternoon the following persons arrived and entered the

chapel, Teodora Alonzo, mother of Rizal, and his sisters, Lucia, Maria,

Olimpia, Josefa, Trinidad and Dolores. Embracing them, the accused bade

them farewell with great strength of character and without shedding a tear.

The mother of Rizal left the chapel weeping and carrying two bundles of

several utensils belonging to her son who had used them while in prison.

A little after 8 in the evening, at the urgings of Seior Andrade, the

accused was served a plate of tinola, his last meal on earth. The Assistant of

the Plaza, Señor Maure and Fathers March and Vilaclara visited him at 9 in

the evening. He rested until 4 in the morning and again resumed praying

before the altar.

At 5 this morning of the 30th, the lover of Rizal arrived at the prison

accompanied by his sister Pilar, both dressed in mourning. Only the former

entered the chapel, followed by a military chaplain whose name I cannot

ascertain. Donning his formal clothes and aided by a soldier of the artillery,

the nuptials of Rizal and the woman who had been his lover were performed](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rphchapter2-lesson9chapter3-lesson10-12-240827044758-79a47c70/85/RPH_-CHAPTER-2-lesson-9_CHAPTER-3-LESSON-10-12-docx-36-320.jpg)

![ Historical interpretation is at the heart of historical analysis, and

historians interpret the past based on primary sources as evidence.

Some historical interpretations suffer from oversimplification,

inadequate evidence, and tentativeness.

The Battle of Mactan was oversimplified; based on the evidence,

Lapulapu was not the young warrior we imagine him to be, and he

did not personally kill Magellan. The battle was won because of the

Mactan's warriors, whose strategy and sheer number easily

defeated the Europeans.

A closer analysis of primary accounts of the first Catholic Mass show

that it did not happen in Masao, Butuan, but instead in Limasawa,

Leyte.

Rizal may have retracted his statements against the Catholic faith.

Still, scholars agree that this does not tarnish Rizal's heroism today.

Angeles, J. A. (2007). The Battle of Mactan and the Indigenous Discourse on

War. Philippine Studies 55(1 pp. 3—52.

Bernad, M. A. (1981). Butuan or Limasawa? The Site of the First Mass in the

Philippines. A Reexamination of Evidence. Kinaadman: A Journal of Southern

Philippines 3, pp. 1—35.

Escalante, R. (2019). Did Rizal Die a Catholic? Revisiting Rizal's Last 24

Hours Using Spy Reports. Southeast Asian Studies 8(3), pp. 369—386.

pigafetta, A. (1969). First Voyage Around the World. Manila: Filipiniana Book

Guild.

Escalante, R. (2019). Did Rizal Die a Catholic? Revisiting Rizal's Last 24

Hours Using Spy Reports. Southeast Asian Studies 8(3), pp. 369—386.

Retrieved 4 February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHJ1

GMA Public Affairs. (2017). Lapu Lapu. I Witness. Retrieved 4 February 2021

from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHJ2

Pigafetta, A. (1874). First Voyage Around the World. London: Hakluyt

Society.

Retrieved 4 February 2021 from: http•]/bit.ly/RdgsPHJ3

PODKAS. (2021). Did Rizal Retract? [Podcast). Retrieved 4 February 2021

from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHJ4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rphchapter2-lesson9chapter3-lesson10-12-240827044758-79a47c70/85/RPH_-CHAPTER-2-lesson-9_CHAPTER-3-LESSON-10-12-docx-38-320.jpg)

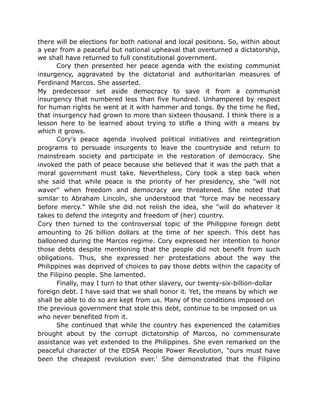

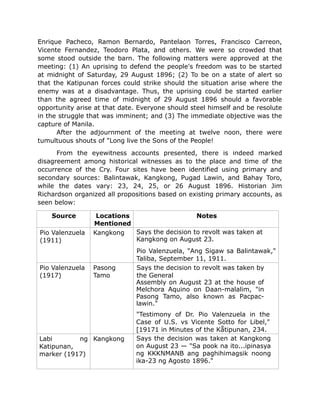

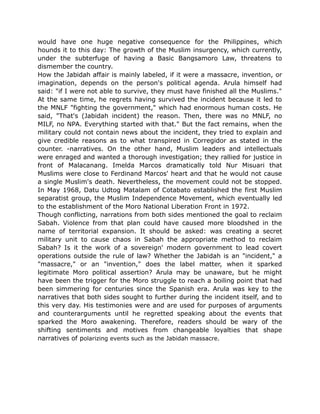

![Medina in Ronquillo, llang talata, 208.

Tomas Remigio

(1917)

Kangkong Says the decision was taken at Kangkong —

"nanditoy amin na ngang pinasiyahang

ituloy ang revolucion..."

Tomas Remigio, Untitled memoir [c. 1917]

in

Borromeo-Buehler, The Cry of Balintawak,

178.

Pio

Valenzuela

(c.i 920s)

Pugad

Lawin

(location

not

specified)

Says the revolutionists met in Kangkong on

August 22, but the decision was taken on

August 23 at Juan Ramos's place at Pugad

Lawin, and the "CM followed the decision.

Pio Valenzuela, "Memoirs," [c. 1920s]

translated by Luis Serrano, in Minutes of

the Katipunan, 102.

Julio Nakpil

(1925)

Kangkong Says the "primergritd' was raised at

Kangkong on August 26.

Julio Nakpil, "Apuntes para la historia de La

Revoluci6n Filipino de Teodoro M. Kalaw," in

Julio

Nakpil and the Philippine Revolution, with

the

Autobiography of Gregoria de Jesus (Manila:

Heirs of Julio Nakpil, 1964), 43.

Sinforoso San

Pedro (1925)

Kangkong Says the decision was taken in Kangkong.

Quoted in Sofronio G. Calderon, "Mga

nangyari sa kasaysayan ng Pilipinas

ayon sa pagsasaliksik ni Sofronio G.

Calderon" (Typescript, 1925), 211—2.

Ramon

Bernardo

[attrib. JR] in

Alvarez

(1927)

Bahay Toro Says the decision was taken and affirmed

("pinagkaisahan at pinagtibaY') on August

24 at Bahay Toro, but says the place

belonged to Melchora Aquino.

Alvarez, The Katipunan and the Revolution,

254.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rphchapter2-lesson9chapter3-lesson10-12-240827044758-79a47c70/85/RPH_-CHAPTER-2-lesson-9_CHAPTER-3-LESSON-10-12-docx-51-320.jpg)

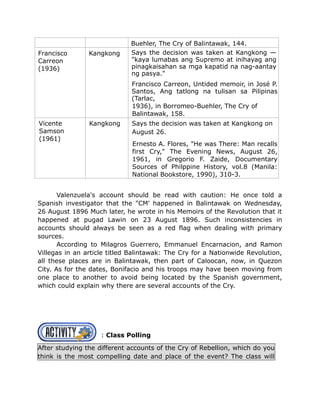

![Guillermo

Masangkay

(1929-57)

Kangkong Says in 1929 and 1957 that the decision was

taken at Kangkong, giving the date as

August 26. Agoncillo's notes of an interview

with Masangkay in 1947, however, says he

recalled the date was August 24.

1929: Guillermo Masangkay, draft article

written in response to a statement by Pio

Valenzuela that had been published in La

Vanguardia, n.d., in BorromeoBuehler, The

CryofBalintawak, 102; 112.

1947: Teodoro A. Agoncillo, "Pakikipanayam

sa Kgg.

Guillermo Masangkay, noong ika-ll Oktubre

1947," in Borromeo-Buehler, The Cry of

Balintawak, 182.

1957: Arturo Ma. Misa, "Living Revolutionary

Recalls

Freedom 'Cry'," The Saturday Weekend Mirror,

August 24, 1957, cited in Borromeo-Buehler,

The Cry of Balintawak, 36-7.

Cipriano

Pacheco

(1933)

Kangkong

and

Pugad

Lawin

(location

not

specified)

Says the decision was taken at Kangkong,

("nang ipahayaå na ang pinagkasunduan...")

but that the revolutionists then went to a

place "nearbV' known as Pugad Lawin

(location not specified), where Bonifacio

announced the decision and cedulas were

torn.

José P. Santos, "Ang kasaysayan sa

paghihimagsik ni

Heneral Cipriano Pacheco," Lingguhan ng

Mabuhay, Disyembre 3, 1933, cited by

Medina in Ronquillo, llang talata, 675-6.

Briccio

Pantas (c.

1935)

Kangkong Says he witnessed the debate in Kangkong

on whether the revolution should be

launched but left before the decision was

made.

Briccio Pantas, Undated declaration [c. 1935]

given to José P. Santos and included in his

unpublished manuscript, "Si Andres Bonifacio

at ang Katipunan," 1948, in Borromeo-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rphchapter2-lesson9chapter3-lesson10-12-240827044758-79a47c70/85/RPH_-CHAPTER-2-lesson-9_CHAPTER-3-LESSON-10-12-docx-52-320.jpg)

![Richardson, J. (2019). Notes on the "Cry" ofAugust 1896. Unpublished

Manuscript. Retrieved 4 February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHKl

Rusling, J. (1903). Interview with President William McKinley. The Christian

Advocate. Retrieved 4 February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHK2

Stradling, R. (2003). Multiperspectivity in history teaching: A guide for

teachers. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Zaide, G., & Zaide, S. (1990). Documentary Sources of Philippine History.

Volume 7. Manila: National Book store, 269-286; 301-309.

Guerrero, M. C., Encarnacion, E. N., & Villegas, R. N. (1996). Balintawak:

The Cry for a Nationwide Revolution. Originally published in Sulyap Kultura,

Quarterly Magazine. National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 1996.

Retrieved 4 February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHK

PODKAS. (2021). What happened in the Cavite Mutiny? [Podcast]. Retrieved

4 February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHK3

PODKAS. (2021 When and where did the Cry of Rebellion take place?

[Podcast].

Retrieved 4 February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHK4

PTV (Philippine Television Network). (2013, 21 January). Xiao Time: Ang

pagaaklas sa Cavite [YouTube video]. Retrieved 4 February 2021 from:

http://bit. ly/RdgsPHK5

PTV (Philippine Television Network). (2015, 20 August). Xiao Time: Ang

Unang Sigaw ng Himagsikan sa Balintawak, Caloocan [YouTube video].

Retrieved 4 February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHK6

Richardson, J. (2019). Notes on the "CM' of August 1896. Retrieved 4

February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHK1

Reading and Analyzing Interpretations. Read the excerpt below

and answer the questions that follow

"That night of August 19, Andres Bonifacio, together with Jacinto, Procopio

Bonifacio, Teodoro Plata and Aguedo del Rosario slipped through the cordon

of Spanish sentries, reaching Balintawak before midnight. Pio Valenzuela](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rphchapter2-lesson9chapter3-lesson10-12-240827044758-79a47c70/85/RPH_-CHAPTER-2-lesson-9_CHAPTER-3-LESSON-10-12-docx-59-320.jpg)

![Excerpts from Jibin Arula's account of the Jabidah

Massacre (Arguillas, 2009)

On the Sabah claim

They said we started the fight. Then, when conflict besets Malaysia

and they complain to the United Nations, the Philippine president could say

that it was the Philippine Muslims who claim Sabah as their own. The

Philippine government will make it appear as if we were private soldiers of

the Muslim sultan and not the Philippine military. The patches [in our

uniform were just skulls [and not the Philippine flag].

On the Massacre

I had to find a way to have the (petition] letter sent to Malacanang. I

went to the pier in Corregidor, without the knowledge of officials. I saw the

guard, he was from our place, near our village. His name was Abhoud Tay.

He was from the Philippine Navy. I gave him the letter and told him to mail

the letter at the post office when he reaches Manila... The next day, March 3,

at around 3 p.m., we were summoned, seven of us. Four of us hid. The three

showed up. They were brave. I was worried. It was only yesterday when we

sent the letter. They even mentioned Col. (Eduardo) Martelino.

But I remember that after March 3, the other trainees were

wondering. Someone joked that in Muntinlupa, those who were sentenced to

die on the electric chair were fed good food. They even slaughtered a goat

for us. At 4 a.m. of March 18, the truck returned. The soldiers told us to

wake up, they said the plane was waiting. I woke up my groupmates. Let’s

go, I said. In one room, there were 24 of us. We were the first to go. Our

fellow trainees woke up and dressed up. I was dressed already because of

what I saw earlier. There were three of us who were relatives, and we talked

about our suspicions. When everyone had dressed up, Lt. Batalla and Lt.

Nepomuceno told us to hurry up. We boarded the truck, 12 of us Muslims sat

together.

So, I told my companions, but we spoke in Taosug so the others would

not understand us, I told them the Ilocanos are armed. The officials are

armed. We are not. They did not return our firearms since we were

disarmed. Some said, 'maybe they won't let us become soldiers after all.'

Another said, 'maybe they will send us home.' We kept on talking while the

truck was moving. When we reached Malinta Tunnel, it was very dark, the

magazine of the carbine of an Ilocano trainee fell. My uncle, who used a

carbine, said, 'watch out. He must have made a mistake. The safety lever

and the release catch of the magazine are near each other. The trainee is a

rookie, so he probably pressed the release catch instead of the safety lever.'](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rphchapter2-lesson9chapter3-lesson10-12-240827044758-79a47c70/85/RPH_-CHAPTER-2-lesson-9_CHAPTER-3-LESSON-10-12-docx-70-320.jpg)

![But even if we prepare, I said, we are helpless. We have no weapons. 'Even

then,' he said. So, we prepared.

When he said lineup, we lined up. We put down our bags. We had

barely stood. They were ahead of call us about his mother 15 meters or God.

away. I heard They turned nothing around, from my 9ced11

us. I didn't hear anyone companions. I was the sixth, in the middle of the

line-up. They all fell. When I looked to my left and right, they had all fallen.

Bloodied.

Excerpts from Ninoy Aquino, Jabidah! 9pecial forces of

Evil? 28 March 1968

JABIDAH! Who is Jabidah? What is Jabidah?....

It is a codename for a supposedly super-secret, twin goaled operation

of President Marcos to wipeout the opposition—literally, if need be—in

operation1969 and to set this country on a high foreign adventure. It is the

codename, Mr. President, for Mr. Marcos' special operation to ensure his

continuity in power and achieve territorial gains. It is an operation so

wrapped in fantasy and in fancy that—pardon the pun, Mr. President—it is

not at all funny.... it jumps out as too fantastic, too unreal and too make-

believe, except the facts and the figures, the personages, are all there.

And what is the truth? But before I unfold here the sorry and sordid tale

behind the Corregidor Affair, Mr. President, permit me to explain why I

checked out of my scheduled privileged speech last Thursday afternoon, the

afternoon after the so-called Corregidor massacres smashed out in the

banner headlines of the metropolitan dailies. I checked out for three

reasons: Firstly, after interviewing the self-asserted massacre survivor, Jibin

Arula, doubt nagged me that there had indeed been a massacre, many more

massacres.

Secondly, I had to check out the international repercussions. Thirdly, I

wanted to check and verify the story where it started, at its roots

In fact, as the newsmen who joined me and I found out, they [the

secret plans] were talked about as freely by the people on the islands as

were smuggling and the other nefarious operations in the southern backdoor

On Simunul Island, I saw the recruiting base for a special forces’ unit called

"Jabidah" and their camp, "Camp Sophia", named after the beautiful 18-

year-old Muslim maiden taken for a wife by the commanding officer of the

Jabidahs, Major Abdullatif Martelino. Camp Sophia was the recruiting station

for the Jabidahs.. .. I brought with me, Mr. President, pictures showing the

camp and all the things that went with it.... This is the badge of the

Jabidahs. (Senator Aquino digs into his coat pocket, shows a military badge).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rphchapter2-lesson9chapter3-lesson10-12-240827044758-79a47c70/85/RPH_-CHAPTER-2-lesson-9_CHAPTER-3-LESSON-10-12-docx-71-320.jpg)

![Aquino, B. S. Jr. (1968, 28 March). "Jabidah! Special Forces of Evil?" by

Senator Benigno S. Aquino, Jr. Official Gazette. Retrieved 4 February 2021

from: http:// bit.ly/RdgsPHL2

Arguillas, C. (2009, 16 March). "Q and A with Jibin Arula: 41 years after the

Jabidah Massacre." MindaNews. Retrieved 4 February 2021 from: http://bit.

ly/RdgsPHL3

Coates, A. (1968). Rizal: Philippine Nationalist and Martyr. Hong Kong:

Oxford University Press.

Cruz, H (1906). Kun Sino ang Kumathå né "Florante", Kasaysayan Né Bühay

Ni Francisco Baltazar at Paguulat Nang Kangyang Karununüa't Kadakilaan.

Manila: Libreria Manila Filatélica, pp. 187—188.

Curaming, R. A. (2020). Power and Knowledge in Southeast Asia: State and

Scholars in Indonesia and the Philippines. Oxon: Routledge.

Curaming, R. A., & Aljunied, S. M. K. (2013). On fluidity and stability of

personal memory: Jibin Arula and the Jabidah massacre in the Philippines. In

I-oh, K. S., Dobbs, S., ahd Koh, E. (Eds.), Oral history in SoutheastAsia, pp.

83—100. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Galvez, D. (2019, 21 September). Enrile claims Jabidah massacre 'invented'

by Ninoy. Inquirer.net. Retrieved 4 February 2021 from:

http://bit.ly/RdgsPHL4 Kunting, A. F. (2018). Sa Gilid ng Himala: Mga Moro

sa Kapangyarihang Bayan 1986. Saliksik 7(2), pp. 287-313.

Majul, C. A. (1985). The contemporary Muslim movement in the Philippines.

Berkeley: Mizan Press

Al Jazeera English. (2018, 19 March). Jabidah at 50: Unresolved massacre

stalling peace talks. [YouTube video]. Retrieved 4 February 2021 from:

http://bit.ly/ RdgsPHL7

Martial Law Museum. Retrieved 4 February 2021 from:

https://martiallawmuseUm.Ph

PODKAS. (2021). Did the Jabidah Massacre happen? [Podcast). Retrieved 4

February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHL8

PODKAS. (2021 ). What was that history book called Tadhana Podcast

Retrieved

4 February 2021 from: http://bit.ly/RdgsPHL9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rphchapter2-lesson9chapter3-lesson10-12-240827044758-79a47c70/85/RPH_-CHAPTER-2-lesson-9_CHAPTER-3-LESSON-10-12-docx-75-320.jpg)