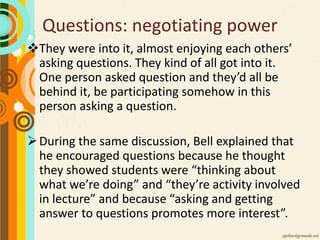

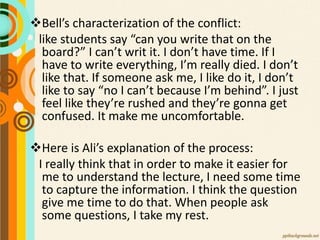

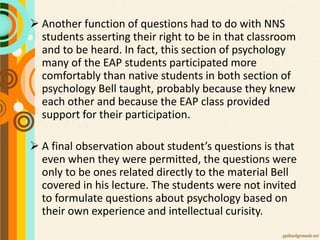

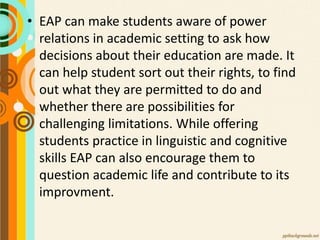

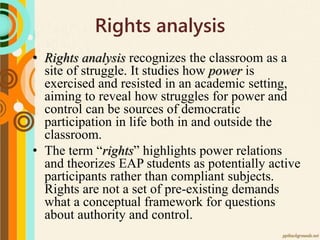

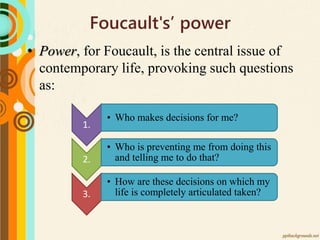

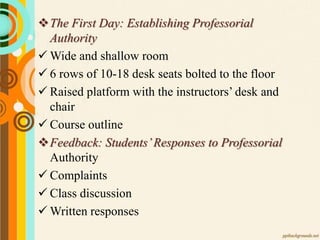

This document discusses using rights analysis to examine power dynamics in academic settings. It analyzes how students negotiate and resist professors' control over assignments and class discussions. While needs analysis focuses on teaching academic skills, rights analysis considers how power is exercised and students can participate democratically. The document also discusses how coverage-focused lectures assert institutional control over faculty and students, and how student questions can resist non-stop lecturing and assert their right to participate. Rights analysis aims to reveal power struggles that can promote democratic participation both in and outside the classroom.

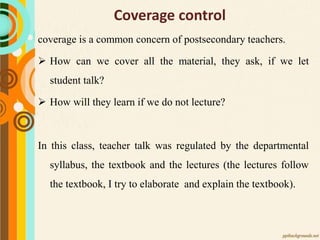

![We recognize that you Can’t do every thing in a

one-semester course. So we just decided what

would be a basic minimum with some choices.

There weren’t really that many choices. They

[the sections] cannot differ that much.

Though Bell upheld the coverage tradition, he

recognized that it was not working well. Many

students, native and non-native, could not

keep up with the pace of the lecture. They

could not listen and take notes at the rate

required for Bell to cover all 12 topics in his

syllabus.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rightsanalysis-151220134932/85/Rights-analysis-9-320.jpg)