This document discusses various topics related to optimizing OLTP performance in Oracle databases, including:

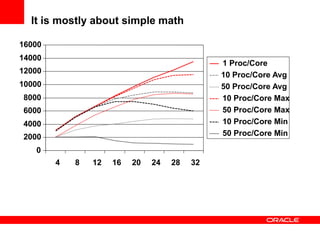

1) Database performance principles such as acceptable CPU utilization levels and how user response times are affected by utilization levels above 60-65%.

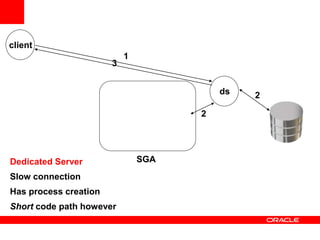

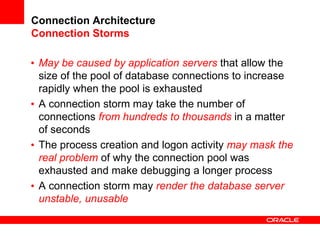

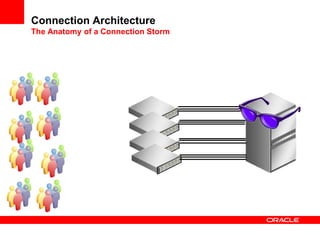

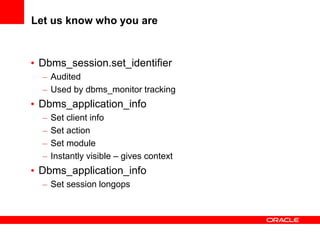

2) Different connection architectures including dedicated servers, shared servers, and database resident connection pooling and their tradeoffs in terms of connection speed and code path length.

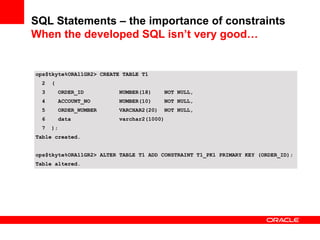

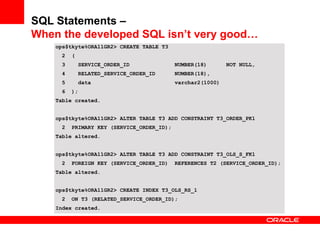

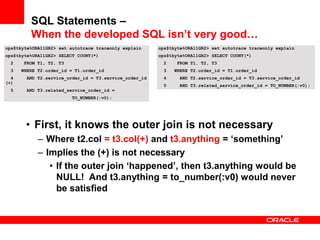

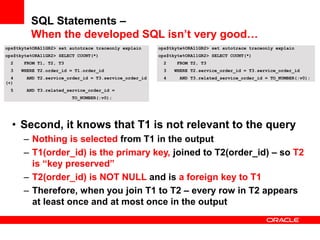

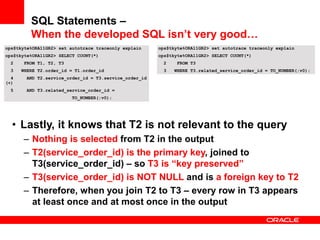

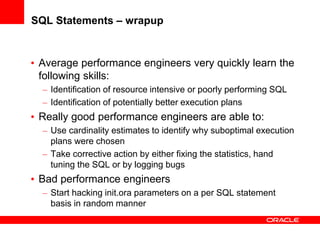

3) The importance of writing efficient SQL statements and maintaining proper schema statistics to enable the database to choose efficient execution plans.

4) Best practices for SQL optimization such as validating join conditions, indexes, partition pruning strategies, and parallelization levels are emphasized.