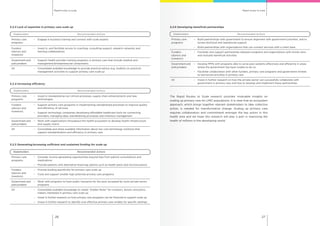

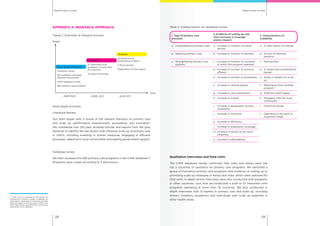

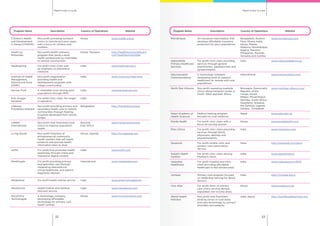

The report outlines the challenges and opportunities in scaling up primary healthcare in low and middle-income countries, emphasizing the importance of collaborative efforts from various stakeholders to improve health outcomes. It identifies six key mobilizers essential for successful primary care models, including strong patient relationships and innovative staffing models, while also addressing significant barriers such as lack of funding and skilled workers. The research culminates in actionable recommendations for stakeholders to effectively scale primary care services and enhance access to affordable health interventions.