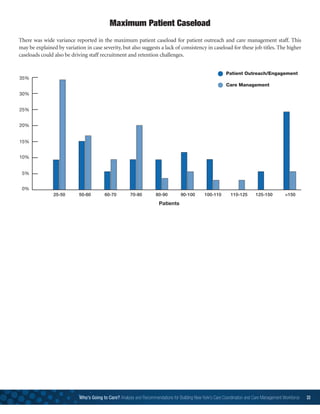

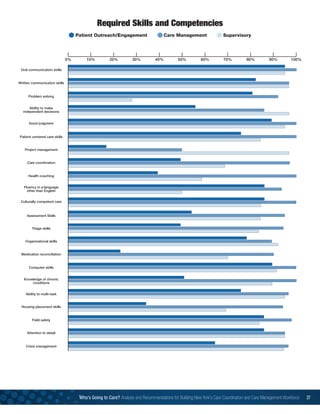

This document analyzes the care coordination and care management workforce needs in New York State. It conducted a survey of 49 Health Home organizations. Key findings include: 1) A diverse set of clinical, organizational and interpersonal skills are needed for these roles; 2) Ongoing training is still needed despite many skills being required; 3) Recruitment and retention challenges exist due to insufficient salaries, high caseloads and lack of skills; 4) Job titles are still evolving. Recommendations include collecting workforce data, requiring all payers to support these roles, ensuring sufficient wages and benefits, and providing ongoing training, certification programs and career ladders. Addressing the workforce challenges is critical to healthcare transformation efforts in New York

![Who’s Going to Care? Analysis and Recommendations for Building New York’s Care Coordination and Care Management Workforce 31

Key Comments:

Caseloads are large and clients are very needy.

Information technology as it applies to the care managers and supervisors in their day to day work and reporting

requirements is an important need.

We have challenges in training new staff given the wide range of chronic illnesses across a caseload. We would like

[training] resources available on a regular basis to send new hires.

Managing all the paperwork needed for such large caseloads is difficult.

Understanding behavioral health needs of clients is a challenge.

Training Challenges](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4f2d29da-6898-49b1-acab-d379c9b2e316-160915164914/85/carecoordinationreportfinal2-31-320.jpg)