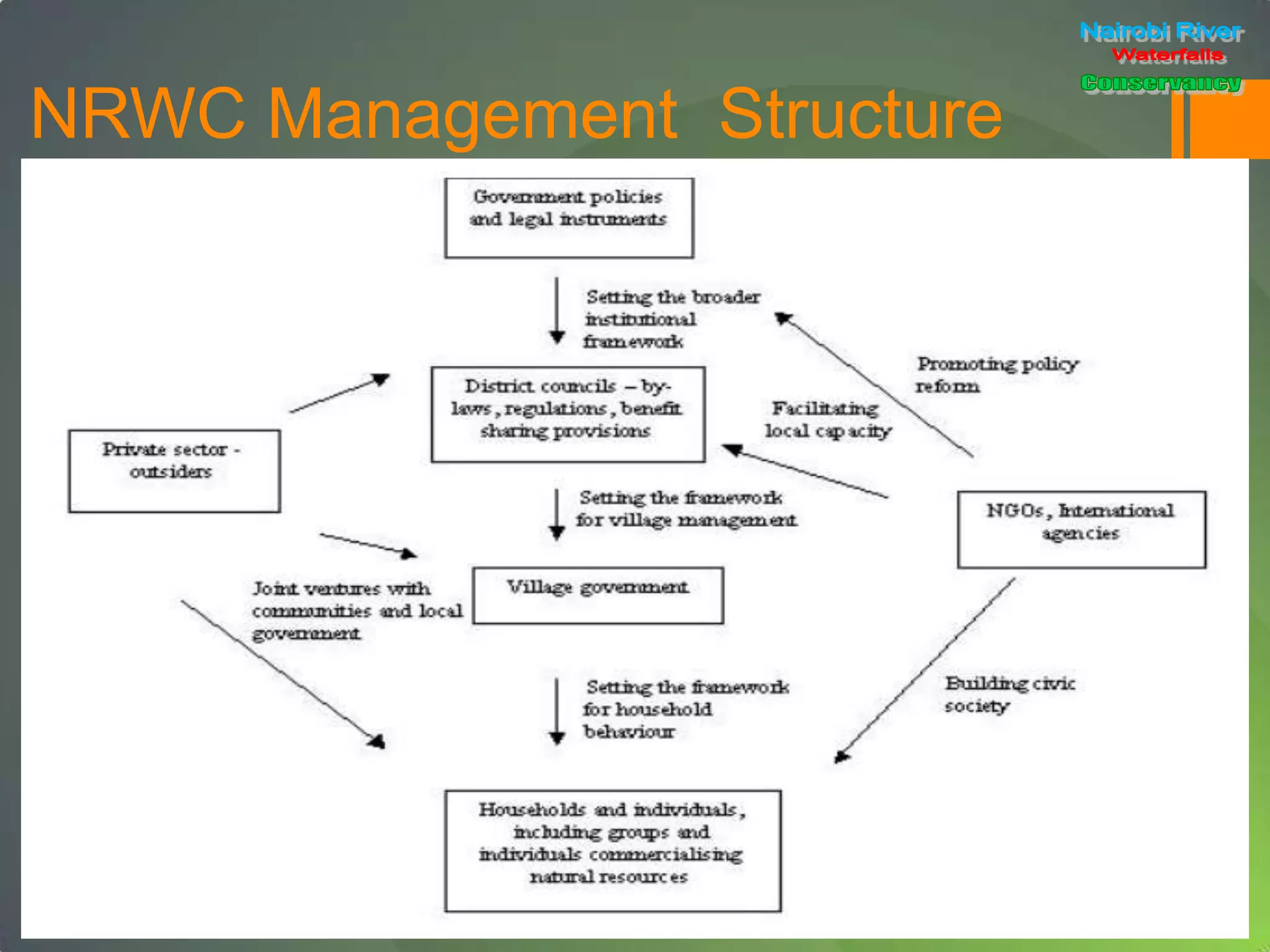

The document outlines proposed organizational structures for community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) in Nairobi, emphasizing four main types based on different stakeholders. It highlights various case studies demonstrating the impact of local governance, community involvement, and external support on the success of resource management initiatives. Recommendations include enhancing the authority of village organizations and establishing a trust for the Nairobi River Waterfalls Conservancy to ensure sustainable management and community engagement.