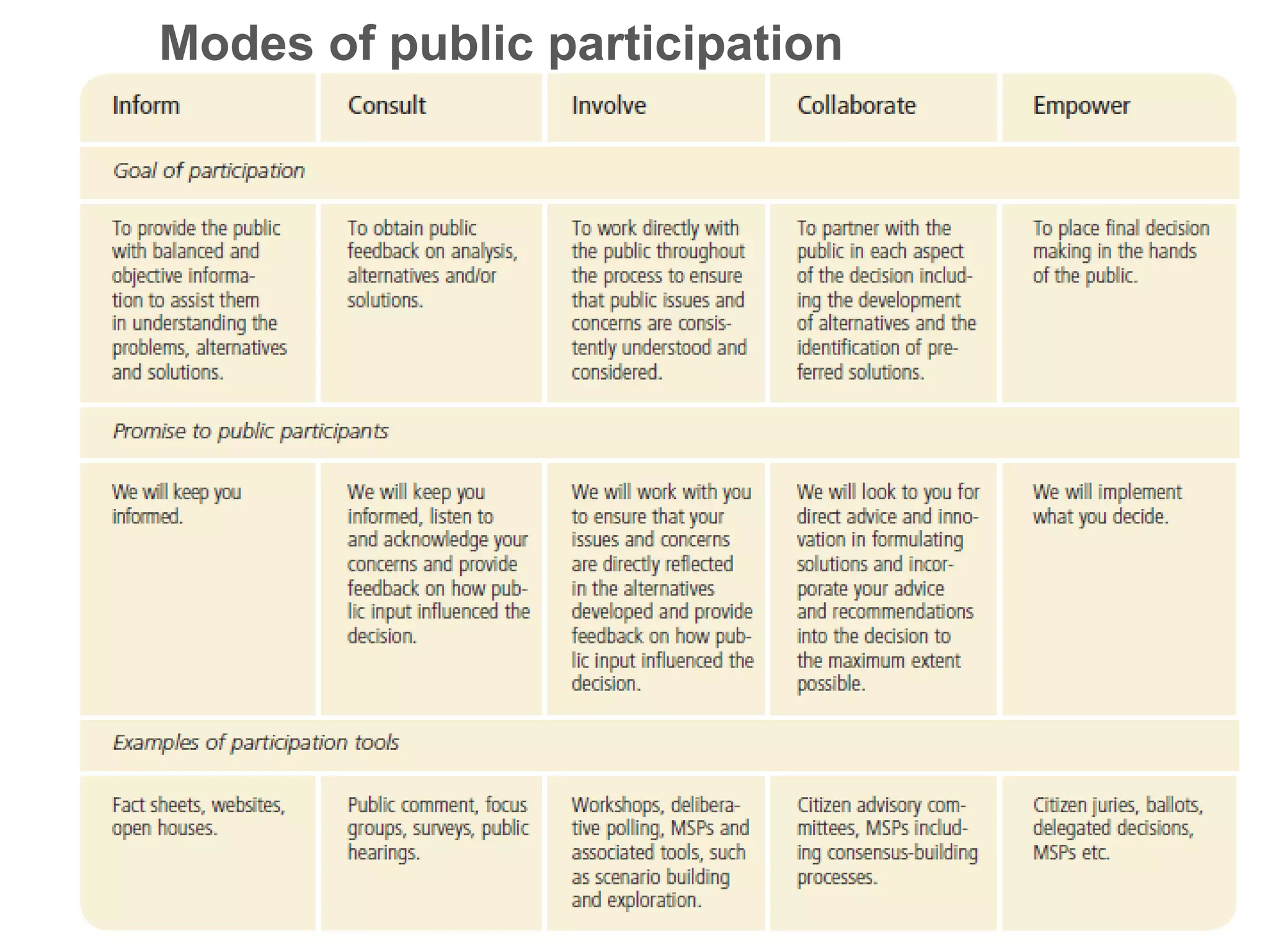

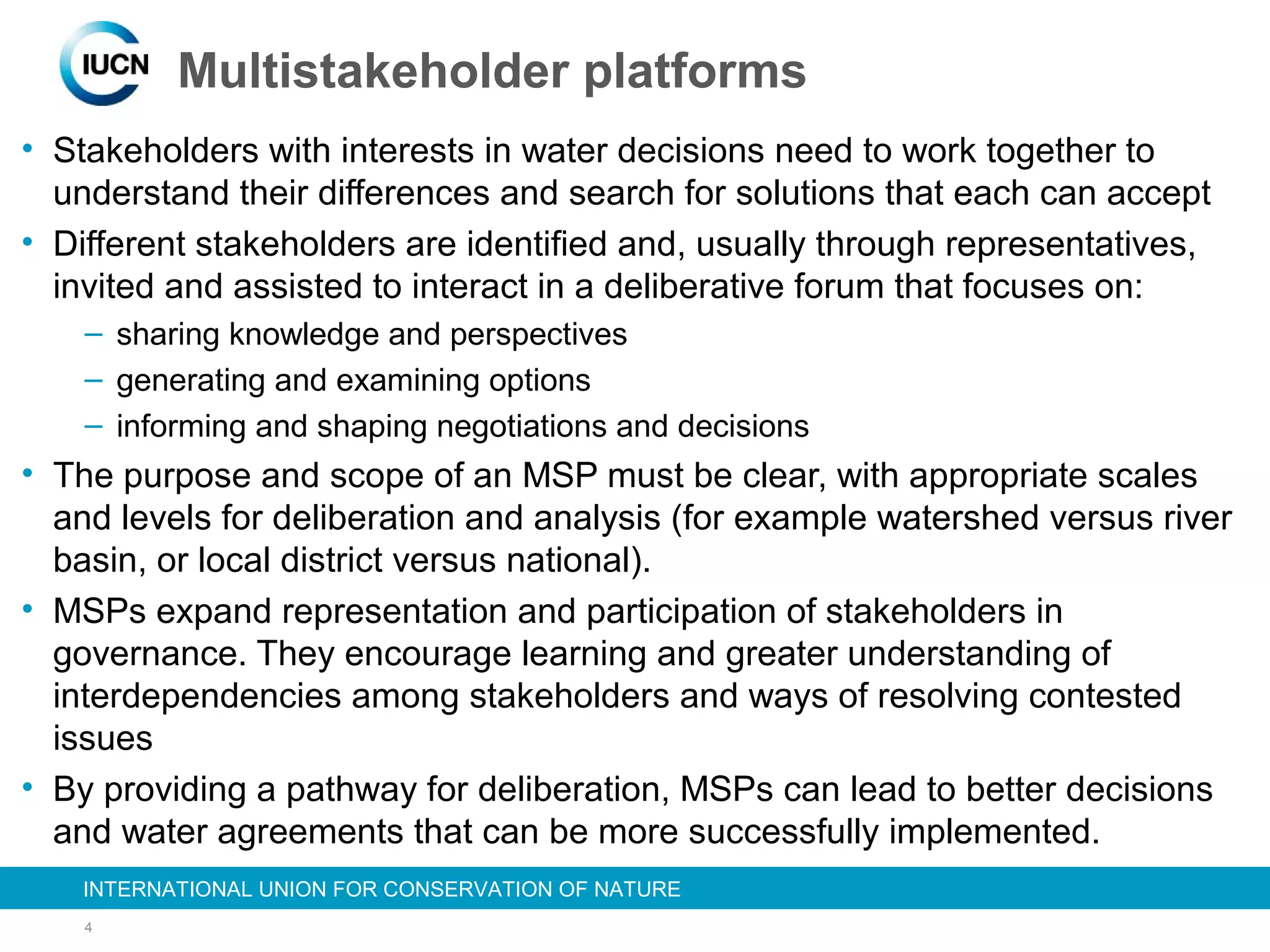

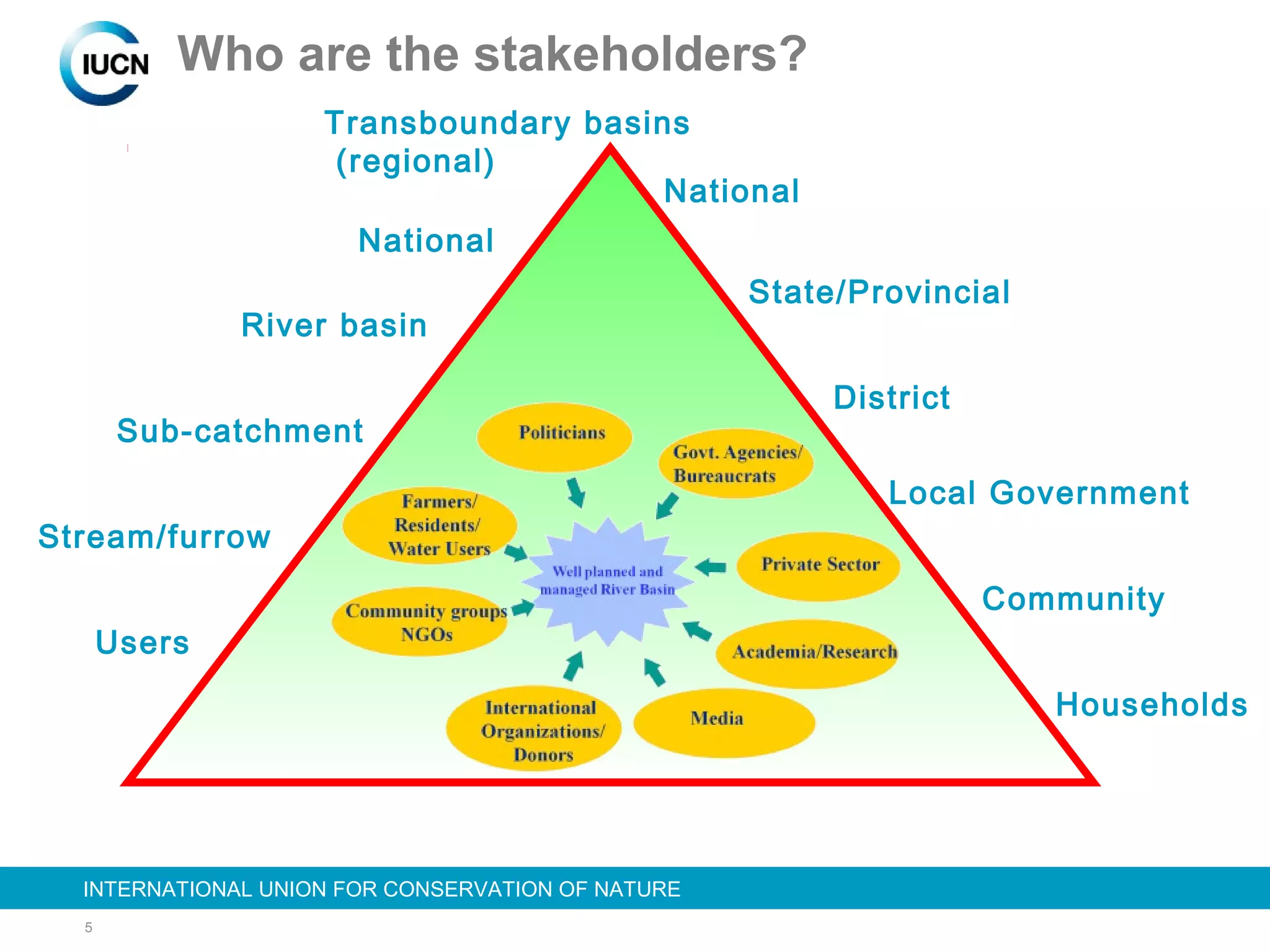

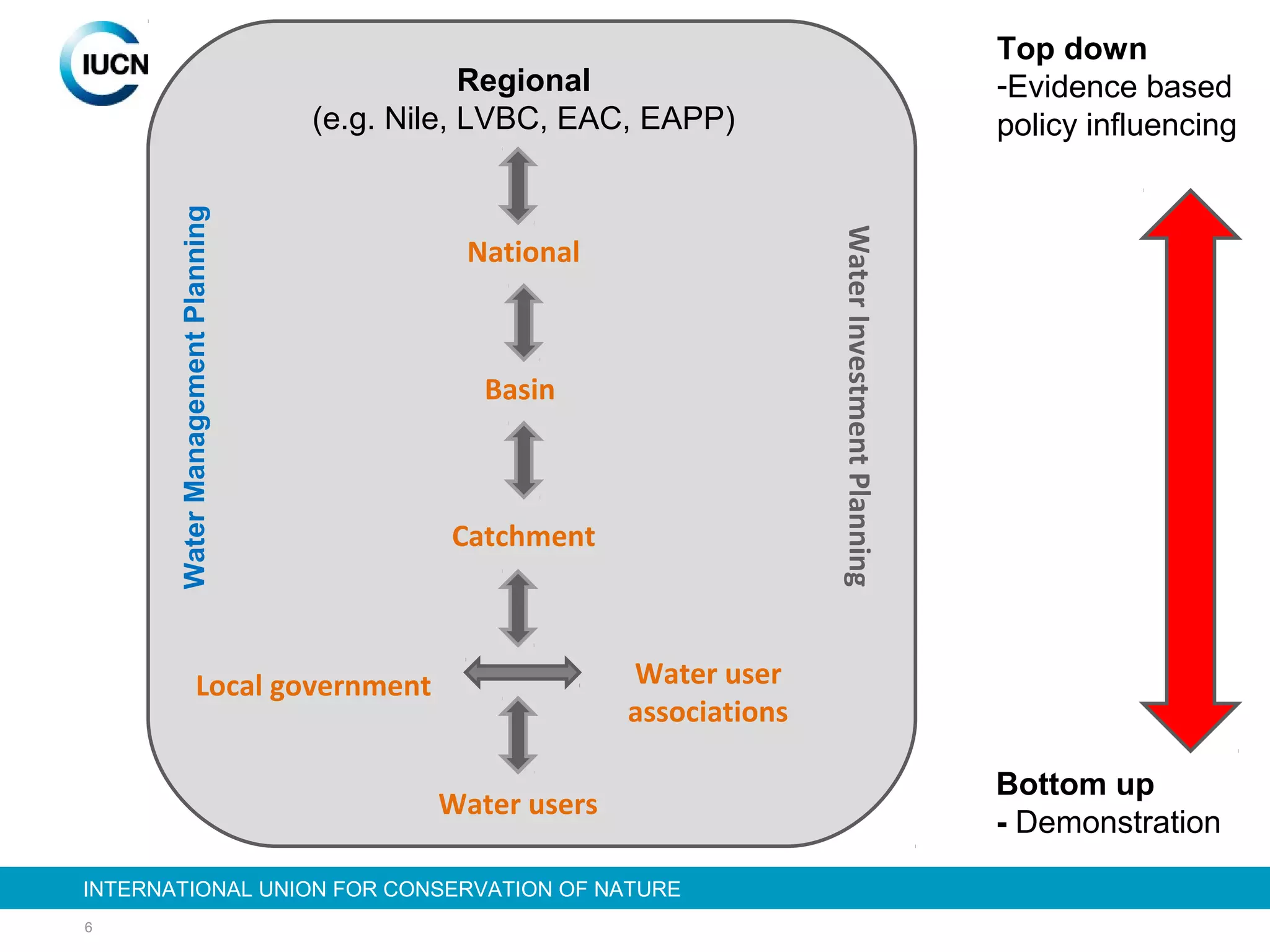

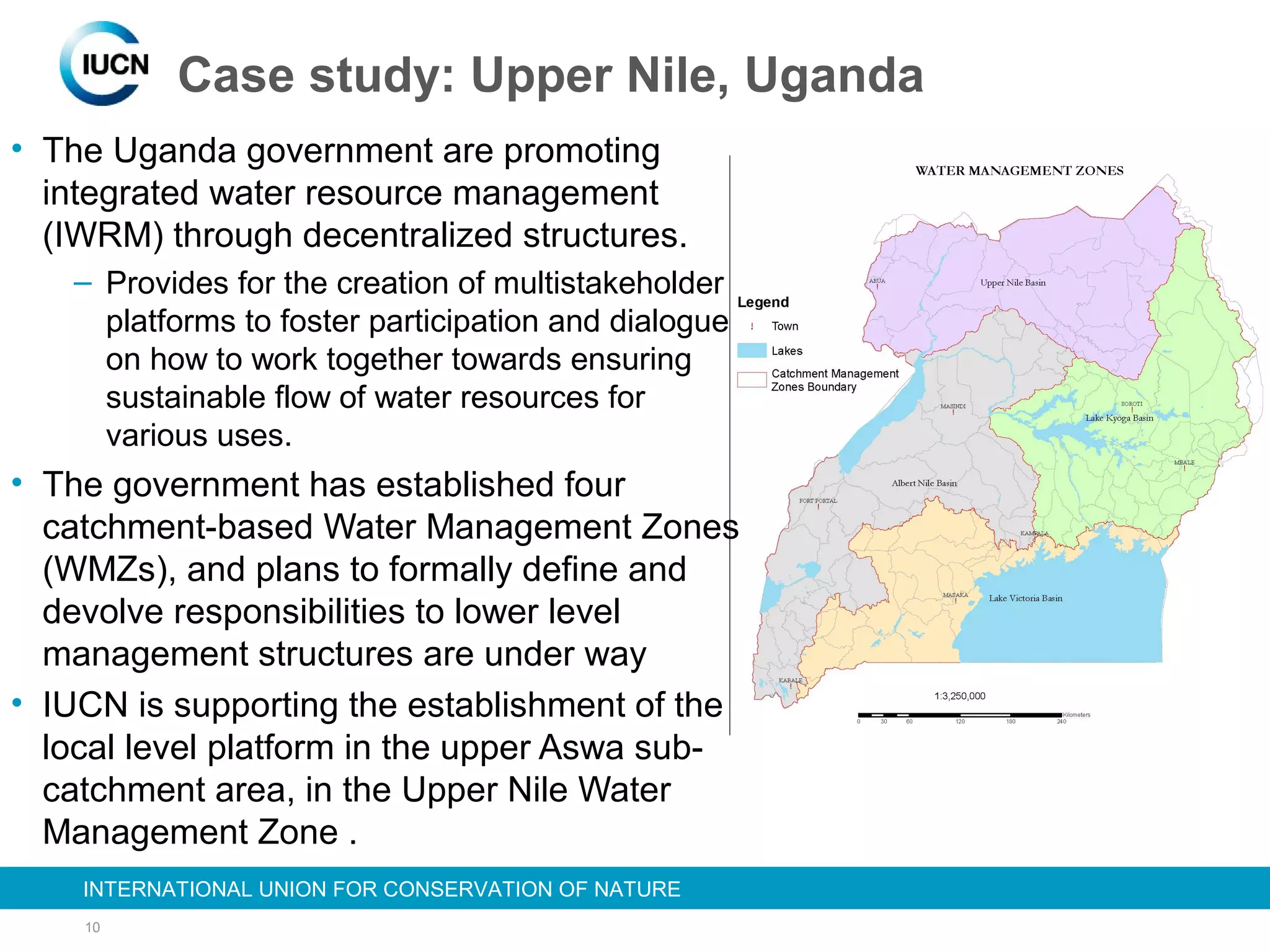

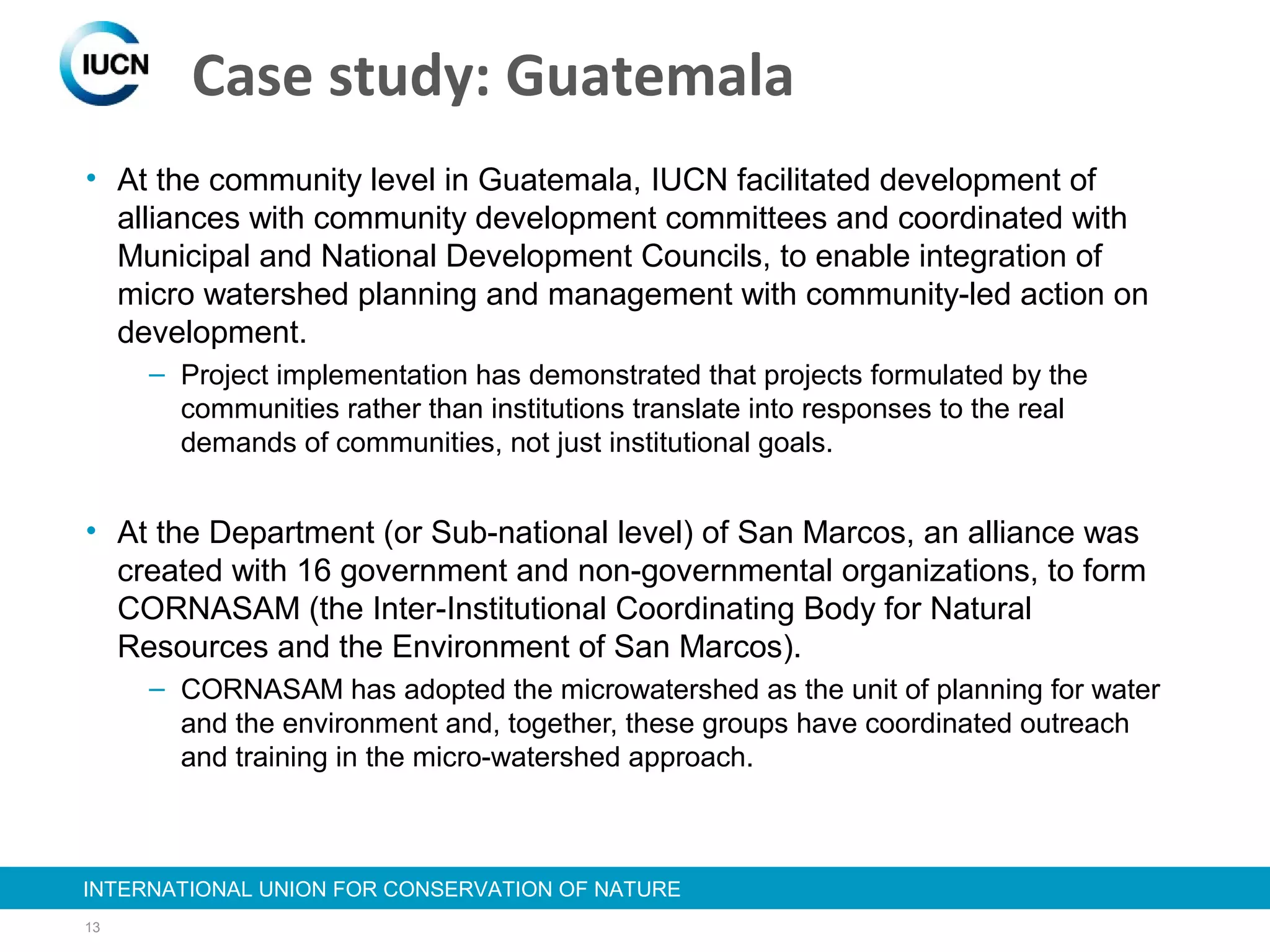

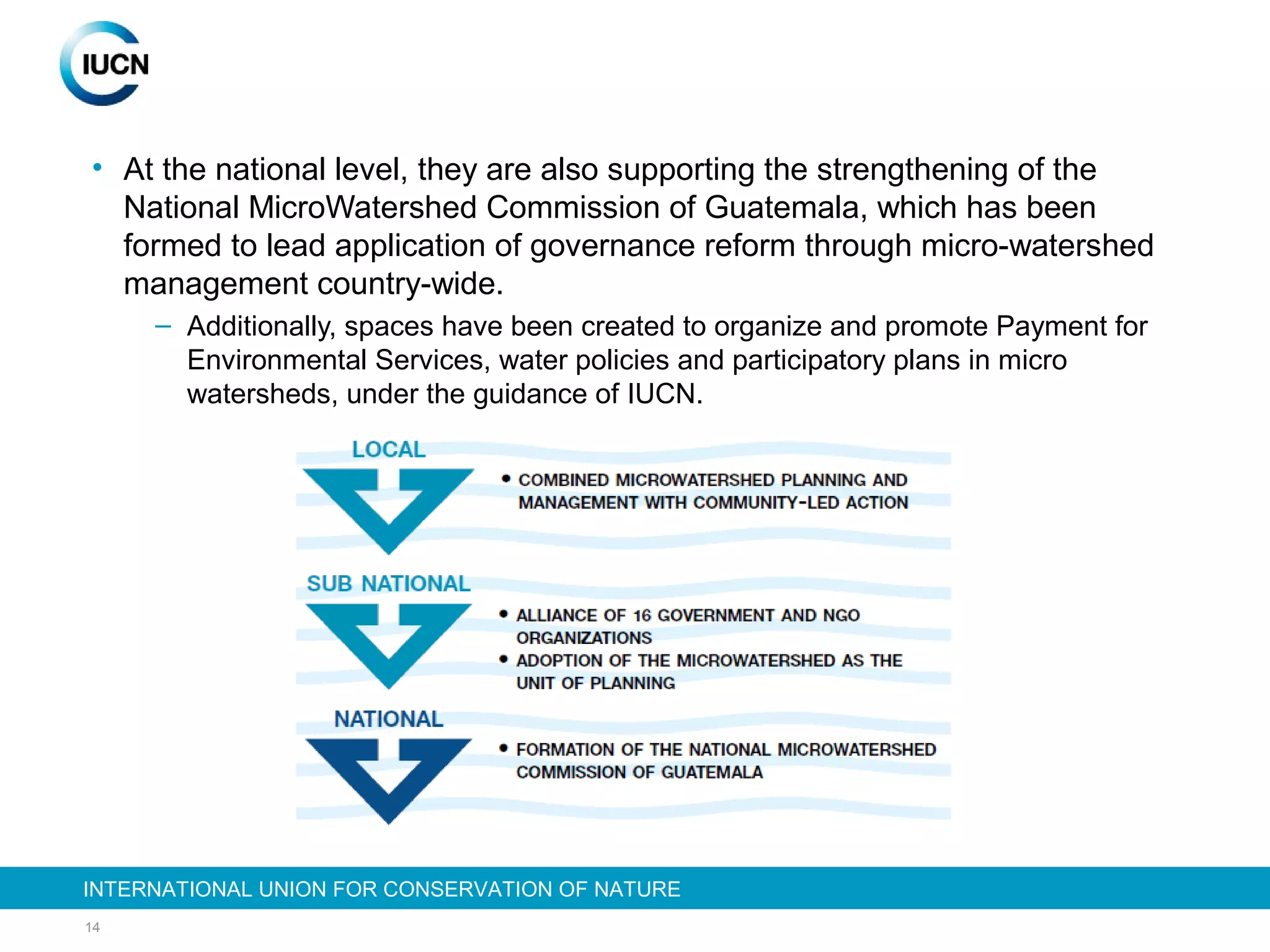

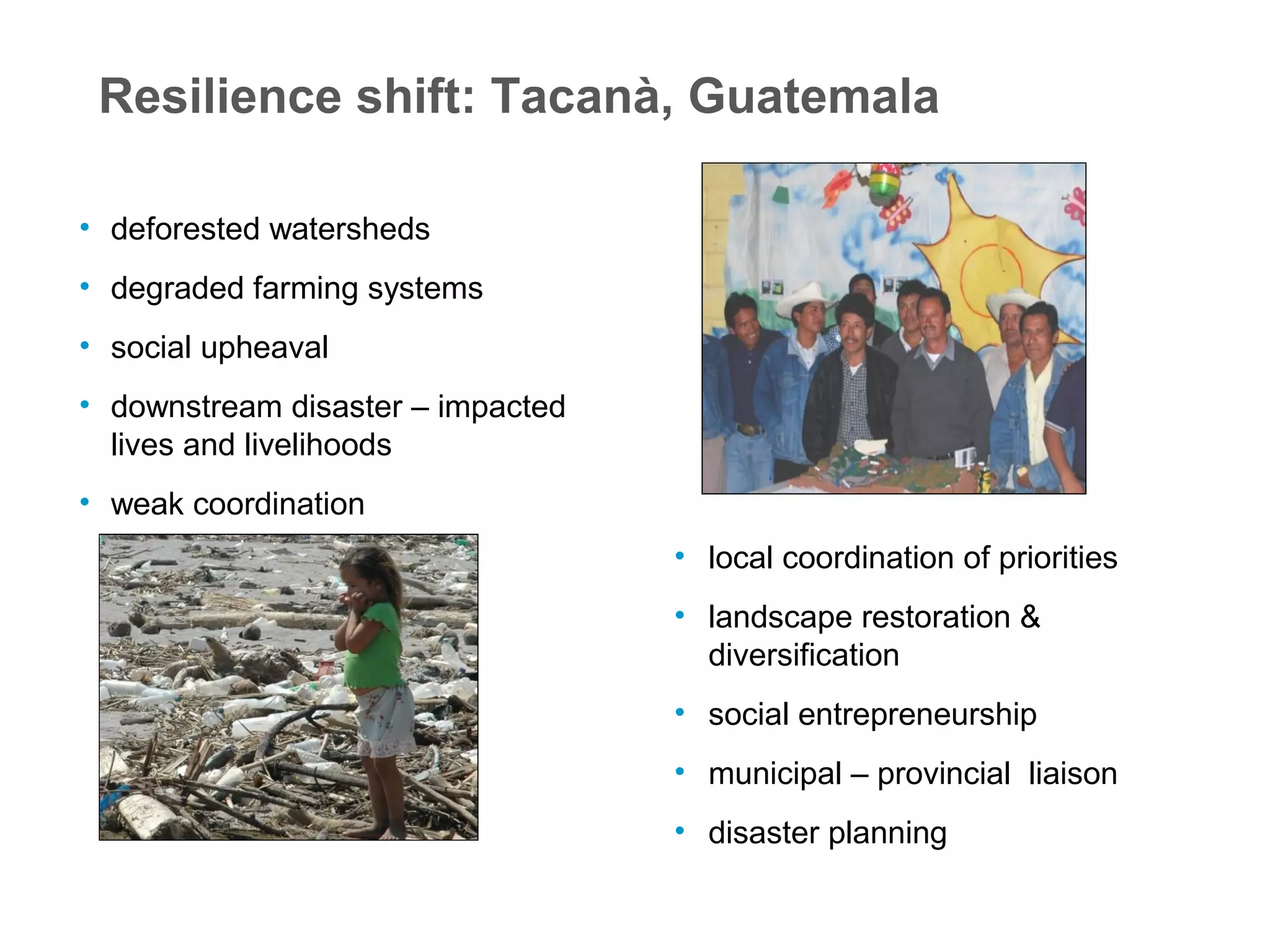

The document discusses good practices in public participation for water governance. It outlines modes of participation including multistakeholder platforms that bring together stakeholders to share knowledge, generate options, and inform decisions. Case studies from Tanzania, Uganda, and Guatemala demonstrate engaging stakeholders from top-down and bottom-up through tools like water user groups and watershed planning. Effective governance requires enabling policies, social learning institutions, decentralized decision-making, coordination across scales, and leadership to build adaptive capacity through participation.