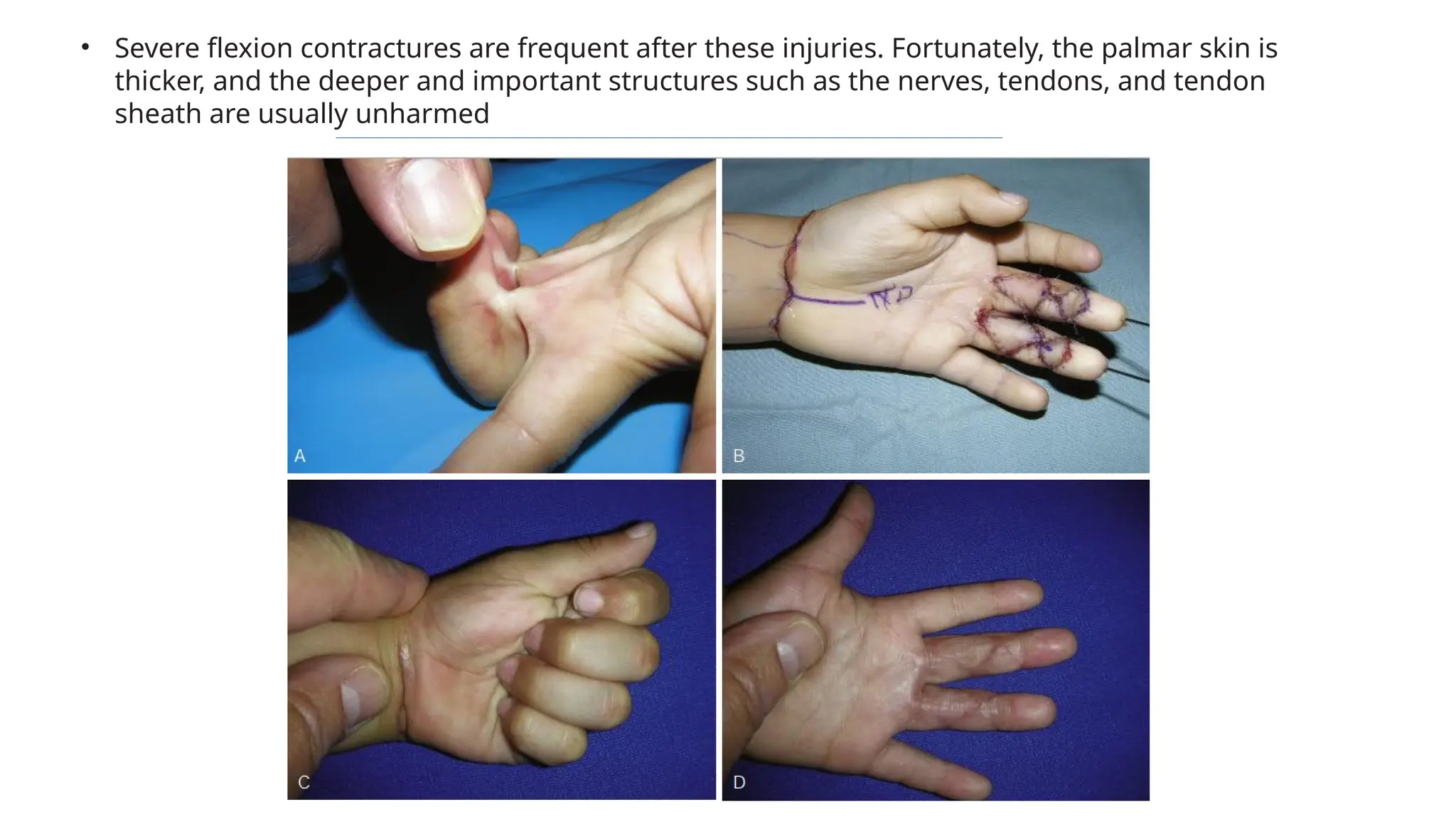

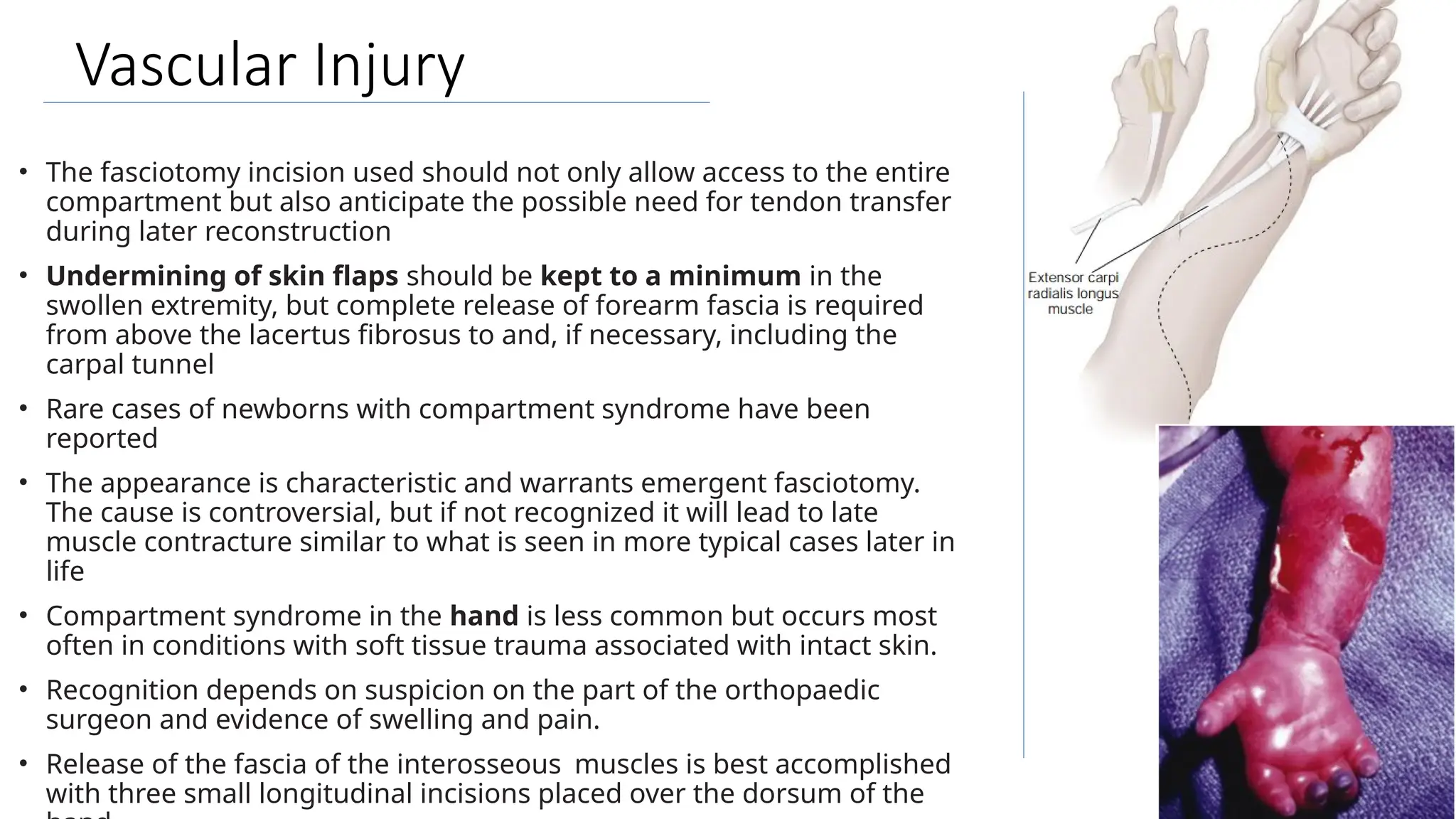

The document outlines the principles of acute hand care in children, emphasizing the importance of early and accurate diagnosis, particularly regarding tendon, nerve, skin, bone, and vascular injuries. It discusses appropriate examination techniques, treatment protocols, and the necessity for careful follow-up, while highlighting the differences in managing pediatric injuries compared to adults. A critical focus is placed on understanding the anatomy and potential complications involved in hand injuries to optimize rehabilitation and outcomes.