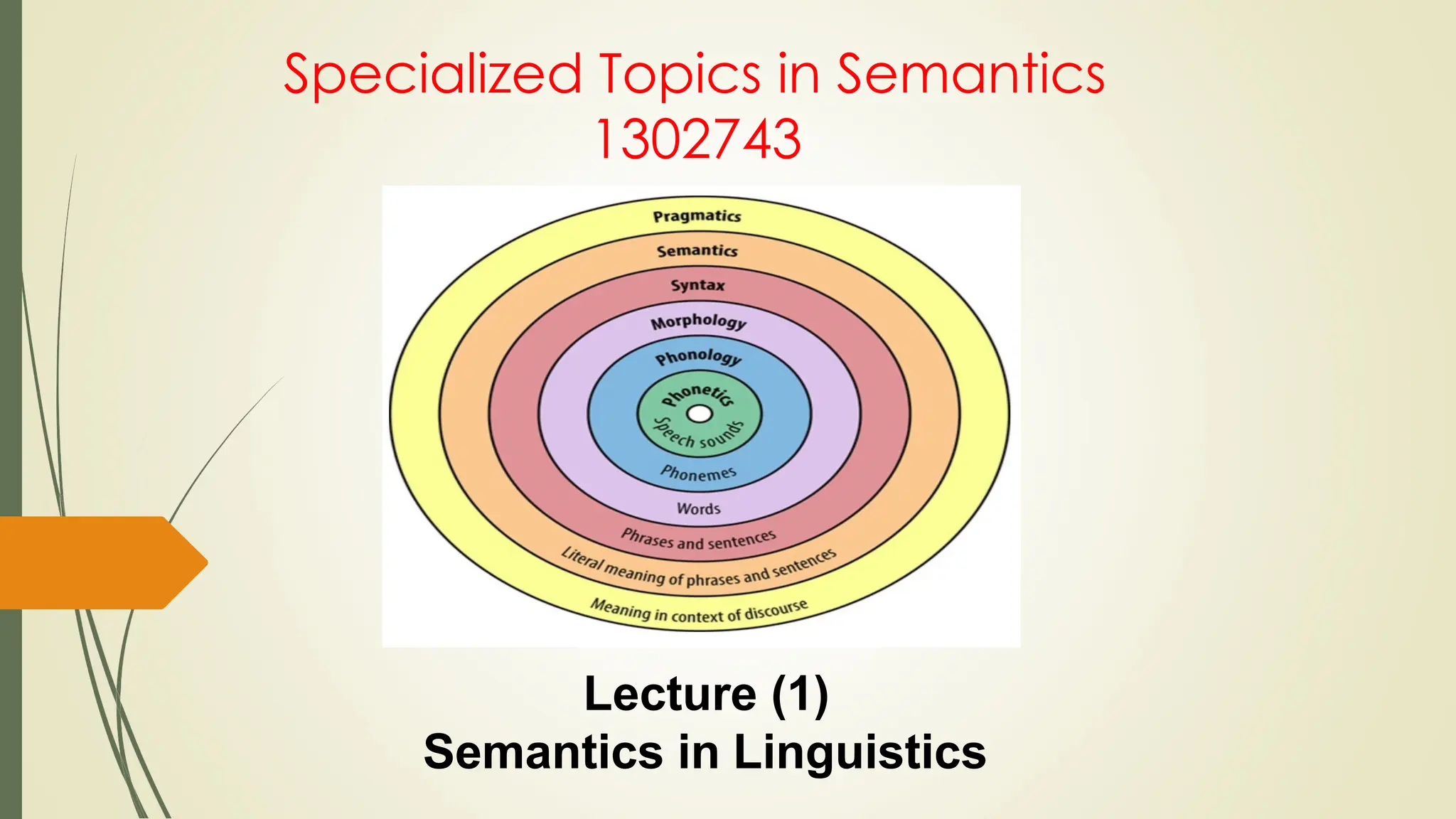

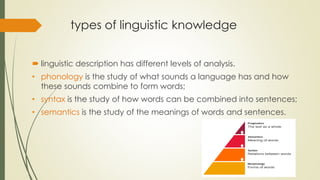

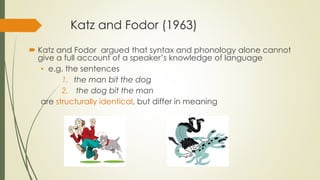

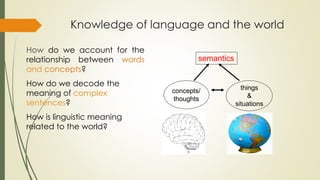

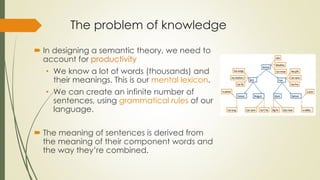

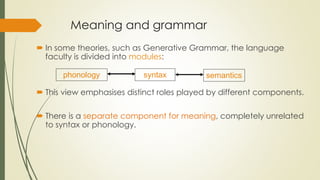

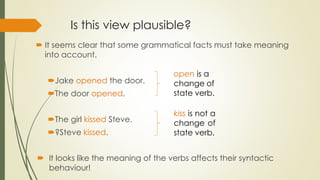

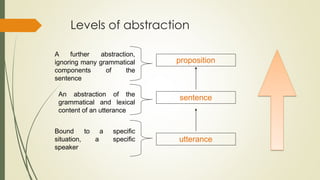

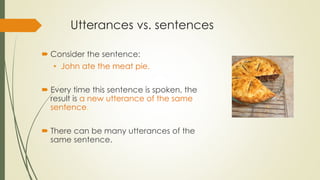

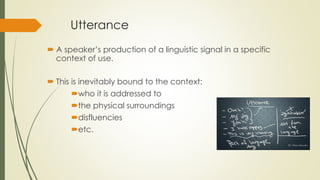

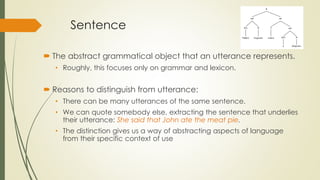

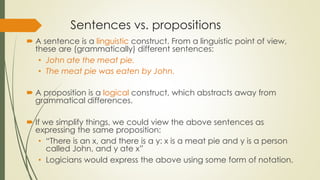

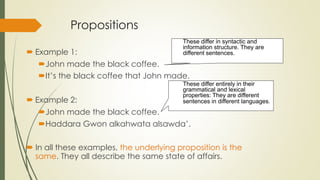

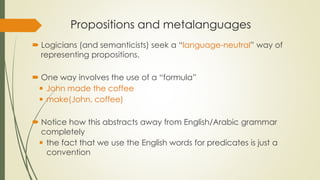

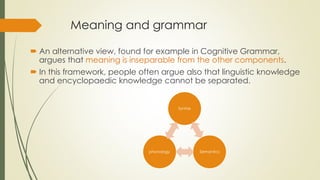

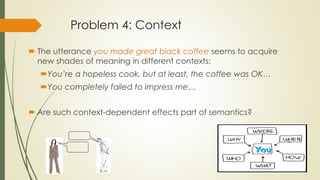

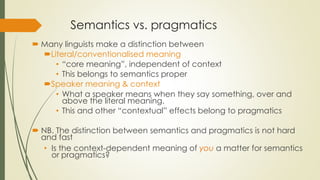

The document discusses semantics in linguistics, explaining how it is involved in understanding the meanings of words and sentences. It highlights the different types of linguistic knowledge and the relationship between language, meaning, and context, addressing challenges in defining semantics independently of world knowledge. Additionally, it examines the compositionality of meaning and the distinction between semantics and pragmatics, emphasizing the complexities of interpreting language in various contexts.