1) Photography emerged through centuries of experimentation and gradual discoveries, with the basic chemistry established by the late 18th century.

2) The first permanent camera images were produced in the 1820s by Joseph Niepce, with Louis Daguerre later developing the daguerreotype process.

3) William Henry Fox Talbot invented the calotype process in the 1830s, enabling negatives and multiple prints. Frederick Scott Archer introduced the wet-plate collodion process in the 1850s.

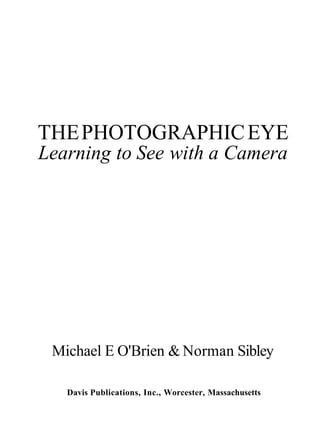

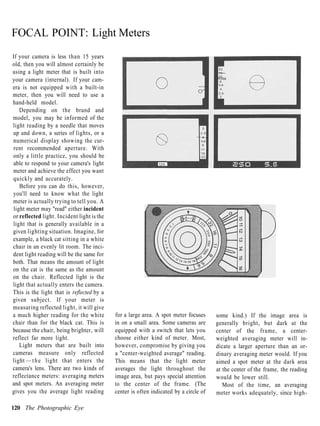

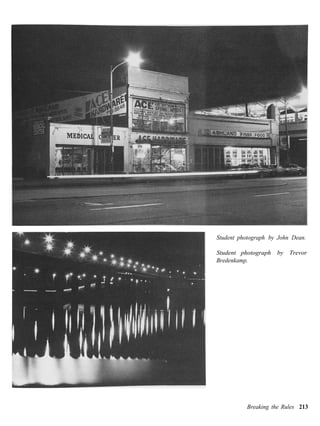

![Photograph Evaluation

Name Period

Assignment

Assignment Requirements

Print Size Choice of Subject

correct meets assignment

incorrect does not meet assignment

Printing Technique

Contrast Print Quality

good good, clean print C fingerprints

I highlights/whites not light enough D dust on negative D tong marks

1 J highlights/whites too light G scratches on negative D uneven developing

. i shadows/blacks not dark enough D air bubbles in processing D incomplete fixing

shadows/blacks too dark . i water spots on negative D etc:

[ . dented emulsion

Print Exposure D negative reversed Reprint and submit again

D good D paper is fogged

D over-exposed (too dark) chemical stains

LJ under-exposed (too light)

D needs dodging:

LJ needs burning:

Composition

Center of Interest Depth of Field Focus

D adequate effective i ] sharp

strong i~l acceptable ' almost sharp

missing D too shallow: [ poorly focused

. should be in focus D effective use of selective or soft focus

Cropping D too deep: D camera shake

LJ effective should not be in focus , moving subject

LJ reposition to correct tilted IH effective use of blurred motion

horizon l i n e

iZ crop tighter:

:

I cropped too tight:

L3 change to vertical format

D change to horizontal format

Originality

Choice of Subject Point of View Comments:

compelling LJ common

D interesting D unusual Work on:

L~J adequate

:'.". dllll

Grade D Please mount this print Extra Credit](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12835048-120507133229-phpapp01/85/Photo-eye-339-320.jpg)