This document provides an introduction and overview of getting started with PhoneGap development. It discusses installing the necessary tools including Node.js, PhoneGap, and the Android SDK. It describes two methods for creating a PhoneGap project - using the PhoneGap command line tools or Eclipse IDE. The document emphasizes that the sample app will be developed specifically for Android, though PhoneGap allows building apps for multiple platforms from the same codebase.

![1. Introduction

This book is going to teach you how to get started with mobile app development using the

PhoneGap platform. We’ll essentially rebuild, from scratch, a basic yet fully-functional app that

really exists! It’s called Japxlate and can be found here in the Google Play Store. The app is a

Japanese dictionary that you can search - even if offline. Not to worry though, we won’t get

bogged down in the nitty gritty of Japanese linguistics. We’ll focus on setting up, building and

finally deploying the app. You’ll laugh, you’ll cry, you’ll sick a little bit in the back of your throat,

but the journey will definitely be worth it…

This is version 1.0 of the book, first published February 2015 (v0.9 first published

January 2014)

Latest source code for the app is at https://github.com/danielrhodeswarp/japxlate-

android

This book was written using PhoneGap v3.1.0, but has been updated to cover anything

new or different in v3.3.0

1.1 Conventions used in the text

A command that you need to type on the Linux command line will look like:

you@yours$ somewhere]$ some linux command to type

Code (of any type - CSS, HTML or JavaScript) that you need to type in will look like:

//does the cursor have random fractals?

function checkRandomFractals()

{

return something.or.other;

}

HTML elements will be referred to like:

<elementname>

Code fragments, variable names, method names etc will look like:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-6-320.jpg)

![4. Getting started

There are two routes we can go down to get started with PhoneGap development. Both routes

require the Android SDK to be installed so let’s do that first. The easiest way to install the Android

SDK is to install the Android Developer Tools (or ADT) bundle. This bundle installs the Android

SDK and Eclipse IDE configured for Android (native) development.

Right, let’s install the Android Developer Tools. The easy peasy way is to download and install

the “ADT Bundle for Linux” from http://developer.android.com/sdk/index.html which should be

worry free.

If you’re already using Eclipse IDE, you can simply download the Android Developer Tools

plugin for it at http://developer.android.com/tools/index.html

..

About IDEs

You aren’t forced to use Eclipse IDE for Android development, though it does make a lot of

things easier as it supports direct deploy to an actual Android device and it has a virtual device

manager for deploying to emulated Android devices.

Myself, I didn’t like the way that Eclipse was opening - and highlighting - the various

frontend source files for the app (though I don’t doubt that this is configurable in the options

somewhere!). There’s also the fact that it doesn’t speak PhoneGap. I found myself cutting the

code in NetBeans IDE and checking in with Eclipse every now and again to deploy to the actual

device (Ctrl-F11) or to check console.log() messages in LogCat.

Netbeans IDE v7.4 dropped just before I finished this tutorial and interestingly that seems to

have PhoneGap (well, Cordova) support built in! Definitely worth a look.

Bizarrely, I found that regardless of the IDE used, I often had to deploy to the device twice

in order to have it truly updated. This happened whenever a resource file was updated, ie.

JavaScript or HTML or CSS. I notice this doesn’t happen when Java sources are edited which

indicates some kind of caching issue. I still haven’t got to the bottom of this particular mystery.

4.1 The cool new way

OK, now we can install PhoneGap itself. For some strange reason that I can’t figure out (I’m

guessing it’s just for package management) it requires NodeJS so go to http://nodejs.org and

install it. Then, as we see at http://phonegap.com/install we simply do (on the command line):

you@yours$ somewhere]$ sudo npm install -g phonegap](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-10-320.jpg)

![Getting started 6

This installs the PhoneGap binaries and commands globally on our system. After that, let’s

actually create the PhoneGap project where we’ll put all of our lovely code for the app. There

are two slightly different syntaxes for this:

you@yours$ somewhere]$ phonegap create --name "Japxlate" --id "com.drappenheimer.japxla

te" japxlate

or

you@yours$ somewhere]$ phonegap create japxlate com.drappenheimer.japxlate "Japxlate"

This will create a PhoneGap project folder structure for building the same code to many

different device targets (Android or iOS etc). "Japxlate" is the name of our app (in quotes).

com.drappenheimer.japxlate is our app’s reverse domain name identifier. All Android apps

have a unique identifier like this. japxlate is our desired folder name for the project. We then

want to do:

you@yours$ somewhere]$ cd japxlate

you@yours$ japxlate]$ phonegap run android

Which will detect your Android SDK and try to run the app on the currently connected device

(or configured virtual machine). If no Android SDK is found or present, it will try to deploy the

app to your account on the PhoneGap remote cloud build environment - which is just out of

beta at time of writing. But you’ll more than likely need an extra bit of setup to get this run

android command to work. Specifically you’ll need to add a couple of folders from the Android

SDK install to your PATH. The gory details are at http://docs.phonegap.com/en/edge/guide_-

platforms_android_index.md.html#Android%20Platform%20Guide, but how I did it was to add

the following lines to my ∼/.bashrc file:

export ANDROID_SDK_HOME=/wherever/you/installed/it/adt-bundle-linux-x86_64-20130729/sdk

export PATH=${PATH}:${ANDROID_SDK_HOME}/platform-tools:${ANDROID_SDK_HOME}/tools

As well as this I personally needed the Java development libraries to be installed.

If the run android command still doesn’t work after all this configuration, double check your

Android SDK Manager which you can reach from the Eclipse IDE.

Note that this run command is a shortcut for the build followed by install commands. If you

don’t want to actually run your PhoneGap app from the command line, you need to at least build

it which is like this:

you@yours$ japxlate]$ phonegap build android

This will create a PROJECTROOT/platforms/android folder with skeleton source files for our app

in it. And importantly the project files for this to be pickupable as an Android project in Eclipse

IDE.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-11-320.jpg)

![Getting started 7

..

How many mobile platforms does it take to

change a lightbulb?

You might be wondering now, if PhoneGap is supposed to be this amazing tool that lets us

write the same app code for multiple mobile platforms, why would we want to dive straight in

to the /platforms/android folder? How is that going to work on, say, iOS?

The answer is simple, PhoneGap is indeed a tool where the same app code can be compiled

for multiple mobile platforms, but - in a nutshell - we are cheating and taking a shortcut! This

tutorial is rather simplified and focuses solely on Android. This is why we dive right in at

/platforms/android.

If your app needs to work on multiple mobile platforms - as most apps do - then you should

really create your app’s code in PROJECTROOT/www, specifying any platform-specific customisa-

tions in PROJECTROOT/merges, then debug each time for your platforms with the build, install

and run commands. The excellent blog post at http://devgirl.org/2013/09/05/phonegap-3-0-

stuff-you-should-know/ explains this very well.

Like the run command, the build command will also fallback to the remote cloud build

environment. You can disable this fallback with the command phonegap local build android.

Right, so now you’ve at least built your app on the command line. You might even have run it

from the command line! Going forward with this tutorial, let’s plug the skeleton code we’ve just

built into our Eclipse IDE as an Android project. Follow these steps:

1. Click File ⇒ New ⇒ Project

2. Select Android ⇒ Android Project from Existing Code (note there’s also a sample native

project in there!)

3. Browse to PROJECTROOT/platforms/android folder (actually just PROJECTROOT seems to

also work)

4. Click OK

5. You’ll get an “Import Projects” dialogue now with the project details that you can confirm

/ change and then click Finish

..

Keeping your PhoneGap up-to-date

Installing PhoneGap via NodeJS has the nice advantage that you can keep your PhoneGap

version up-to-date by running this command:

you@yours$ somewhere]$ sudo npm update -g phonegap](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-12-320.jpg)

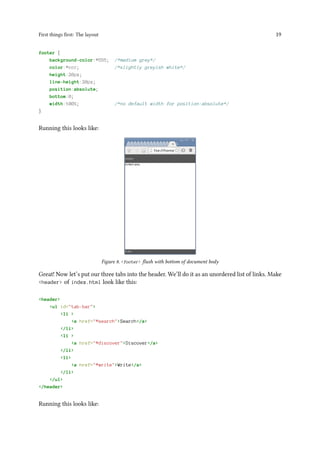

![First things first: The layout 23

density of the device display, they might be too tiny and hard to make out or really massive and

Legoish. But we’ll use them for simplicity.

One alternative would be to use a vector format - such as SVG - for the icons which stores the

image such that it can be scaled up or down without losing information. Another new trend is to

have the browser load something called an icon font. This is like a normal font but where each

character is an icon (remember Wingdings?!). This has the advantage that the icons are sizeable

just like any other text. Also they can be bolded or italicised. But they can only be of one colour.

Go ahead and put all of the PNG icons in assets/www/img (though we won’t use all of them).

Let’s reference some of these icons in our tab markup, change <header> in index.html to look

like this:

<header>

<ul id="tab-bar">

<li>

<a href="#search"><img src="img/search.png"> Search</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="#discover"><img src="img/chat-bubble.png"> Discover</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="#write"><img src="img/file.png"> Write</a>

</li>

</ul>

</header>

Note the space after the image and before the link text. Running this gives:

Figure 13. Icons we sourced are way too big

Woah, those icons are pretty big eh? The icons are a mix of square, tall or wide, but they all have

a biggest side of about 128 pixels. That’s clearly way too big for us here. Let’s use GIMP to resize

search.png, chat-bubble.png and file.png to have a biggest side of 16px - the same as our app

font size (in index.css) [NOTETOSELF double check this]. So go ahead and make those changes

and overwrite the original icon files. While you’re at it, do the same for paste.png because we’ll

be using that later on. (Feel free to trash the other icon files from assets/www/img as we won’t](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-28-320.jpg)

![First things first: The tabbing mechanism 33

..

navigator.notification.alert(message, alertCallback, [title], [buttonName]);

So let’s try that. Stick navigator.notification.alert('Some alert message', null); in the

receivedEvent() function that we were just tinkering with. Running this (which obviously

won’t work in desktop Chrome) gives a spurious error in LogCat:

Figure 20. Error when attempting navigator.notification.alert()

What’s going on? Well, it turns out that “As of version 3.0, Cordova implements device-level

APIs as plugins”. We have to install whichever APIs we want in our project. This removes

bloat as, previously, all APIs came pre-installed in every PhoneGap project. I actually found

this to be a bit mysterious and poorly documented (I found myself mashing up a mix of info

from Cordova docs and PhoneGap docs). But here’s how to add a particular plugin to your

PhoneGap project. Go to anywhere in your project folder structure on the command line and:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-38-320.jpg)

![First things first: The tabbing mechanism 34

..

you@yours$ japxlate]$ phonegap local plugin add https://git-wip-us.apache.org/repos/asf

/cordova-plugin-dialogs.git

From PhoneGap v3.3.0 you can simply type phonegap local plugin add

org.apache.cordova.dialogs

Which should echo:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-39-320.jpg)

![First things first: The tabbing mechanism 35

..

[phonegap] adding the plugin: https://git-wip-us.apache.org/repos/asf/cordova-plugin-di

alogs.git

[phonegap] successfully added the plugin

(Note that you won’t need to run this command, and you won’t get the above error, if you’ve

gone down The fiddly older way as that bundles all plugins into your project).

You’ll get the relevant URL from the docs for whichever plugin at the “API Reference” section at

http://docs.phonegap.com/en/3.1.0/ (PhoneGap has a good list of core and 3rd party plugins at

https://build.phonegap.com/plugins but the installation instructions for each one are seemingly

out-of-date and mention tinkering with XML config files which we don’t need to do after

running the above command.) The above command has downloaded the source for the plugin

and put it in /assets/www/plugins (in this case in org.apache.cordova.dialogs)

but diff on v3.3.0 etc.

It has also added references to the plugin in /assets/www/cordova_plugins.js - a file which

has been there from the start but just as a placeholder stub. The phonegap.js that we include

in our index.html actually also includes cordova_plugins.js so after running the above

command, we have all we need to start using navigator.notification.alert()! Try it again!

It works!:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-40-320.jpg)

![First things first: The tabbing mechanism 38

..

you@yours$ japxlate]$ phonegap local plugin list

[phonegap] org.apache.cordova.dialogs

This command lists all plugins installed in the current project.

you@yours$ japxlate]$ phonegap local plugin remove org.apache.cordova.dialogs

[phonegap] removing the plugin: org.apache.cordova.dialogs

[phonegap] successfully removed the plugin

This command removes the specified plugin from the current project. You specify the plugin

by its reverse-DNS identifier. You can find these out by issuing the above “list” command.

There are plugins to access the mobile device’s camera, accelerometer, phone contacts and

many more. Using these plugins is how we make a full fat mobile app and not just a simple

website-in-a-box.

PhoneGap v3.3.0 also has “Plugman” which is another way of working with plugins.

Plugman lets you add or remove plugins for one specific platform, whereas the above

method will add or remove plugins globally to any and all platforms used in the project.

Please see http://docs.phonegap.com/en/3.3.0/plugin_ref_plugman.md.html.

We’ve just been able to simulate our deviceready event on desktop Chrome for debugging and

we are ready to get our tab taps working. receivedEvent() in index.js is where the magic

happens because by the time we reach there, the device is ready (and the browser DOM is ready

as we’ve put JavaScript includes at the bottom of our HTML). But let’s not go down the route of

stuffing all of our JavaScript in index.js. Let’s go modular - right from the start. Create a new

JavaScript file called:

japxlate.js

in /assets/www/js

and include it from index.html thus:

<script type="text/javascript" src="js/japxlate.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript" src="js/index.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript">

app.initialize();

</script>

Put a function called configureTabs() in the newly created japxlate.js thus:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-43-320.jpg)

![First things first: The tabbing mechanism 42

{

return false;

}

lastTab.parentNode.className = ''; //undisplay

this.parentNode.className = 'current';

//---------------------------

//-----content div display logic---

var lastDiv = document.querySelector('div.current');

lastDiv.className = ''; //undisplay

var matchingDiv = this.getAttribute('data-div-id');

var thisDiv = document.getElementById(matchingDiv);

thisDiv.className = 'current';

//-----------

//get tab div id from tab link

var divId = this.getAttribute('data-div-id');

}

Let’s go through this code, which looks fiddly at first, but basically tinkers with CSS class names

such that things turn on and off as we want.

The first thing we do is the DOM standard preventDefault() which prevents the browser’s

default action for the event from triggering. The default browser action for clicking on a link is

to:

1. Change URL in address bar to that of link target

2. Add new URL to browsing history

3. Load new URL

As our links are simply triggers to load tabs and not proper links, we don’t want any of these

steps to happen. Step [2] is especially annoying. If we don’t call preventDefault() for our tab

taps, if we open our app and click on the tabs ten times, we will have to use the device’s BACK

button ten times to exit the app!

Next we use querySelector() to get the single current tab link. Because ‘this’ in our click handler

will be the clicked element, we can do a check to see if this is the same as the previous current

tab. And if so, do a “no operation” (NOP). We then manipulate classnames to activate only the

clicked tab.

Similarly, we use querySelector() to get the currently active content <div>. We activate the

content <div> for the clicked tab by retreiving data-div-id from the clicked <a> and using that

to get the correct div.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-47-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 48

<div id="search" class="current">

<button type="button" id="search-button" style="float:right; width:45%; margin-righ

t:1%;">

<img src="img/search.png">

Search

<img id="button-spinner" src="img/spinner.gif" style="visibility:hidden;">

</button>

<input type="text" id="search-query" placeholder="Japanese or English" size="40"

style="width:45%; margin-left:1%;">

<br>

<span id="loading-text">

[Loading core dictionary. This takes a while the first time.

<img src="img/spinner.gif">]

</span>

<div id="results-wrapper">

<div id="search-results">

You can search by kanji, hiragana, katakana, English or romaji!

</div>

</div>

</div>

We float our search button right (which means that in the markup it has to come before things on

the same line that would be visually to the left of it) but make it 1% (of total width) away from the

edge for nice appearance. We reuse search.png as a button icon. We also include the spinner.gif

that we just created but default it to visibility:hidden. Why not just display:none? Because

with visibility:hidden, it is hidden but still takes up space in the layout flow. This means the

layout won’t “jump” when we make it appear. We’ll switch this image’s visibility on and off

programmatically.

Then we’ve got our text input which uses the new HTML5 placeholder attribute to present a

hint or instruction to the user about what kind of entry it expects. The text input is also 45% wide

with an edge spacing of 1%.

Why not just make both 50%? Because then they will touch in the middle which will end in tears

with big fingers on a small display!

We then have a “this will take a while” message and spinner that we will remove after one-off

setup is complete.

Finally we have a container for our search results - <div id=”search-results”> - which displays a

default search hint. We also have a wrapper for the search results container - <div id=”results-

wrapper”> - which is going to be the scroll viewport for search results. These two divs need the

following styles in index.css:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-53-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 50

2. Icon for search is screwy again - let’s fix that like we fixed the tab icons.

In index.css, change the existing:

a img

{

vertical-align:middle; /*make more sensible relative to text baseline*/

}

to:

a img, button img

{

vertical-align:middle; /*make more sensible relative to text baseline*/

}

Which covers (2). To fix (1), add this to index.css:

input[type="text"], button {

height:30px;

margin:0;

}

Running looks like this:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-55-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 54

//Check if "edict" table exists and has records

function checkDB(tx)

{

//console.log('checkDB()');

tx.executeSql('SELECT COUNT(id) AS count FROM edict', [], successCheckDB, errorChec

kDB);

}

We call executeSql() on the received SQLTransaction object which needs at least an SQL query

as its first argument (and parameter values as the 2nd parameter if the query in the first argument

uses parameter binding), but can optionally take both a success and failure callback as 3rd and

4th parameter respectively. Here we run a very simple query to get the count of rows - by id

- in the edict table. This query will throw an error if the edict table does not exist (but not if

it exists and is empty which is a condition we will knowingly ignore for this simple app). We

don’t use parameter binding in this query so we provide an empty array as the 2nd parameter

simply because we need to “get” to the 3rd and 4th parameters. We specify an error and a success

callback. Should the query fail we can assume that the table does not exist and therefore needs

to be created and populated. Let’s look at the success callback first as it’s simpler and only has

to clear the “database loading” message:

//Callback for if checkDB() succeeds - ie. "edict" table present and full

//SO clear the "database loading" message

function successCheckDB(tx, results)

{

//console.log('edict already loaded');

document.getElementById('loading-text').innerHTML = '';

}

Pretty easy and not worth explaining other than to point out that the callback function receives

an SQLTransaction and an SQLResultSet object respectively.

Let’s get started on the error callback:

//Callback for if checkDB() fails - ie. no "edict" table

//SO create it and fill it

function errorCheckDB(transaction, error)

{

console.log('edict table not exist - will create and fill');

//here we need to do something to fill the table

}

This code so far will run without errors (but don’t forget include websql_core.js from

index.html (above the japxlate.js include)) but won’t do anything useful. It will get to the

“edict table not exist - will create and fill” log message and then stop. In the error callback, we

need to run another transaction on the Japxlate database which will load all the dictionary data

we need. Change errorCheckDB() to look like this:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-59-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 63

..

Why two search querying routes?

We could get away with not detecting the input query’s language by having this kind of logic:

“Assume the query is English, do a search, if no results then assume it’s Japanese

and search again”

Which has two problems. We have to make an assumption about how our app is being mostly

used. (Admittedly we could change the assumption if we find out it’s wrong.) Another problem

is performance - we may be searching unnecessarily.

A very simple, and linguistically incorrect!, way to do this is to see if we have multibyte

characters in our query string or not. We’ve set our HTML page to be UTF-8. UTF-8 is interesting

because it’s a flavour of Unicode that’s backwards compatible with good ol’ ASCII. ASCII can

be utf-8, but so can Japanese! But ASCII won’t set the right bits in each byte to be considered

a multibyte stream. Something we can use to our advantage is that for ASCII, the length of a

string in bytes will also be the length of that string in characters. For multibyte utf-8 strings, this

will not be the case and the byte length will be greater than the character length.

Let’s implement an is_mb() (“mb” meaning “multibyte”) check using this knowledge. Keeping

things modular, and realising that we are going to need functions soon for Japanese language

handling, make a new file in /assets/www/js called linguistics.js. Add is_mb() thus:

//Does the given utf8 string have multibyte characters or not?

function is_mb(utf8String)

{

return utf8String.length != mb_bytelen(utf8String);

}

Here we compare a string’s length in characters (using the length property - JavaScript operates

internally with utf-16 unicode) with its length in bytes. mb_bytelen() is the key function

here that we need to write. It will give us the byte length for a utf8 string. Put it also in

linguistics.js:

//Get length in BYTES of a utf8 string

function mb_bytelen(utf8String)

{

//Matches only the 10.. bytes that are non-initial characters

//in a multi-byte sequence.

var m = encodeURIComponent(utf8String).match(/%[89ABab]/g);

return utf8String.length + (m ? m.length : 0);

}

In utf-8, everything is a sequence of bytes. For an ASCII character, one byte is the full sequence

- that byte is the character. But it allows for multibyte characters by the initial byte in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-68-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 64

that character’s sequence of bytes setting a special bit. This special bit tells the browser (or

programming language or text editor etc) that “there’s more to come!” and the browser adds

the remaining bytes in the sequence to get the full value for that character. The remaning bytes

also set a special bit so the browser knows when that particular character has all of its bytes read.

For the gory details please see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UTF-8.

So what we are doing in mb_bytelen() is adding the length of the string in characters to the

count of non-initial character sequence bytes. This will give us the total byte length for any utf8

string - containing multibyte characters or not!

OK, is_mb() is one important tool for our database querying logic in the bag. Using it, let’s think

more about our query logic with some pseudocode:

if(is_mb(searchTerm)) {

//searchTerm is Japanese (or at least multibyte)

//

//[1] exact kanji match

//[2] exact kana match

} else {

//searchTerm is English or, as last resort, romaji

//

//[1] exact definition match

//[2] partial definition match

//[3] exact romaji match (on kana field)

}

So, if we detect multibyte characters in the search term, we assume it is Japanese and try to

match it exactly against, first, the kanji field of the words in our database. Then, if that produces

no results, we try to match it exactly against the kana field. This priority order is realistic because

kanji (Chinese idiogrammic characters) are the “correct” way to write a Japanese word. The kana

is just the way to pronounce those Chinese characters. Though note that some words are kana

only and don’t hava a kanji.

We assume that the search term is in English if it contains no multibyte characters. Then we

focus on the definition field of our database. Remember that definition entries look like this:

/uncertain/vague/ambiguous/

Multiple definitions are separated by slashes. So our most relevant results (query [1] of the

English route) would be to find the search term exactly as one of these definitions. A search

for “vague” would match the above definition, for example. If that produces no results, we query

for partial matches of the search term in these definitions. For example a search for “director”

will match a definition of /company director/board member/. Finally, if we still have no

results, we can take a gamble and assume that the user has entered a term in romaji (which

is Japanese written in abc like “sayonara” or “moshimoshi”). For this we’ll have to convert the

search term into phonetic kana and query for a matching kana field. So this one needs a bit more

work programmatically.

Note that if we go down the Japanese route, and get no results at the end, we don’t then proceed

down the English route (and vice-versa).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-69-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 66

//Search edict for an exact kanji match

function queryDB_ja(tx)

{

var safeQ = global_searchTerm;

//use placeholders (so we don't need to escape the query)

tx.executeSql(SELECT * FROM edict WHERE kanji = ? LIMIT + global_maxResultsCount

, [safeQ], successQueryDB_ja, errorWebSQL);

}

We accept an SQLTransaction object - as per the Web SQL specification - and call it tx for short.

We use tx.executeSql() to run a very simple SQL query on the edict table; Matching the kanji

field exactly to the search term. Note how we get the search term from the global variable we

defined earlier.

In the SQL query, we have kanji = ?, the question mark is a placeholder for parameter (or

value) binding. We then specify the value to be bound to this placeholder in the 2nd argument to

tx.executeSql(), in this case safeQ. Why do this? Why not just query for kanji = ' + safeQ

+ ', ie. literally. Well because, this way, if the entered search term contains single quotes or

slashes or anything that Web SQL considers “special”, the SQL query will break and result in

errors. When we use parameter binding, Web SQL is going to escape the parameter value for

us so that we are safe from dodgy characters accidentally breaking our SQL (or malicious “SQL

injection” attacks). You can try this a little later if you like to see how wrong it can go!

So we query with a success callback of successQueryDB_ja() and our all-purpose error handler.

Note that successQueryDB_ja() will be called if the executeSql() query is valid and executes

- which means even if zero results are returned. So successQueryDB_ja() is going to look like

this:

//Callback for if queryDB_ja() did not error (which includes zero results)

//Print kanji matches if we have any ELSE try kana matches

function successQueryDB_ja(tx, results)

{

if(results.rows.length == 0) //no kanji matches - try kana matches

{

//console.log('no ja kanji matches');

//version 1.0, 4 megabytes

var db = window.openDatabase(Japxlate, 1.0, Japxlate DB, 4 * 1024 * 1024);

db.transaction(queryDB_ja_kana, errorWebSQL);

}

else

{

putResultsOnPage(results);

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-71-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 67

We receive the SQLTransaction and an SQLResultSet. We check the rows.length property of

the resultset to see if we got any matches or not. If we have no matches then we open the DB

again and run a different query function on it, namely queryDB_ja_kana() which is going to

search for kana matches against the search term. If we have any matches, we simply call our

putResultsOnPage() function (that we made previously in search_interface.js) and pass it

the resultset. Then we are done with this particular query route. OK, we still need to implement

queryDB_ja_kana(), which - yes you’ve guessed it - is almost identical to queryDB_ja() but

using the kana field:

//Search edict for an exact kana match

function queryDB_ja_kana(tx)

{

var safeQ = global_searchTerm;

//use placeholders (so we don't need to escape the query)

tx.executeSql(SELECT * FROM edict WHERE kana = ? LIMIT + global_maxResultsCount,

[safeQ], successQueryDB_ja_kana, errorWebSQL);

}

We simply print out any and all results that we might have.

We are now ready to give this Japanese query route a test drive! First, include the new JavaScript

files we’ve made at the bottom of index.html so that it looks like this:

.

.

script type=text/javascript src=js/linguistics.js/script

script type=text/javascript src=js/search_interface.js/script

script type=text/javascript src=js/websql_edict_inserts.js/script

script type=text/javascript src=js/websql_core.js/script

script type=text/javascript src=js/websql_search.js/script

script type=text/javascript src=js/japxlate.js/script

script type=text/javascript src=js/index.js/script

script type=text/javascript

app.initialize();

/script

.

.

Run it! Enter an English search term and click the search button. You’ll get a console message of

“doing as english - exact”, and the spinner will start to spin and not stop! We’ve obviously not

finished the English query route yet.

Let’s check if it is really searching for any entered Japanese terms. Go ahead and copy some

random text from http://www.yahoo.co.jp and paste it into our app’s search box. Click search.

You’ll probably get the “no matches found” message (unless you got really lucky!). OK, so that’s

working. What about an actual match? Open up the websql_edict_inserts.js file and copy any](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-72-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 68

kanji or kana INSERT value. Search for this on the app and you should get the corresponding

definition. Nice!

This is pretty awesome right now. It’s beginning to feel like a useful, working app! OK, before

the very final thing we need to implement for searching (I’ll let you guess what you think it is

;-)) let’s tackle that English searching route. Go back to the else clause in doEdictQueryOn() (in

websql_search.js) and edit it to actually do something:

.

.

if(is_mb(global_searchTerm)) //Japanese (or at least multibyte)

{

//console.log('doing as japanese - kanji');

db.transaction(queryDB_ja, errorWebSQL);

}

else //ie. English (or - as last resort - romaji)

{

console.log('doing as english - exact');

db.transaction(queryDB_en, errorWebSQL);

}

.

.

We do what we do for Japanese just with a different query function called queryDB_en() which

is going to do step [1] of our English route and is like this:

//Search edict for an exact English match

function queryDB_en(tx)

{

var safeQ = global_searchTerm;

//use placeholders (so we don't need to escape the query)

tx.executeSql(SELECT * FROM edict WHERE definition LIKE ? LIMIT + global_maxResu

ltsCount, ['%/' + safeQ + '/%'], successQueryDB_en, errorWebSQL);

}

Here we query the definition field of our edict table and note how we use the LIKE operator

and not, as with the Japanese route queries, the ‘=’ operator. LIKE allows us to use wildcard

characters which allows us to do a fuzzier search. We need that functionality here as we are

trying to match only one of each database row’s many definitions (separated by ‘/’).

What’s going on with our 2nd argument where we have to specify the value for parameter

binding? Well, we basically build a LIKE condition that will match, completely, safeQ as ANY

one of the definition entries - first one, last one or any of the middle ones. ‘%’ is the SQL wildcard

meaning “match anything” and actually it will match zero characters if applicable too! With a

definition of:

/one/two/three/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-73-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 69

then the same format of condition like: ‘%/one/%’, ‘%/two/%’, ‘%/three/%’ will match each corre-

sponding definition respectively. We simply build this pattern and put it in the 2nd argument.

We use the general error handler again and the success handler is successQueryDB_en():

//Callback for if queryDB_en() did not error (which includes zero results)

//Print exact matches if we have any ELSE try partial matches

function successQueryDB_en(tx, results)

{

if(results.rows.length == 0) //no exact matches - try partial matches

{

//console.log('no en exact matches');

//version 1.0, 4 megabytes

var db = window.openDatabase(Japxlate, 1.0, Japxlate DB, 4 * 1024 * 1024);

db.transaction(queryDB_en_partial, errorWebSQL);

}

else

{

putResultsOnPage(results);

}

}

This is cut from the same mould as successQueryDB_en() that we’ve just done. If we have

no results from exact matching, we move on to step [2] which is partial matches by calling

queryDB_en_partial():

//Search edict for a partial English match

function queryDB_en_partial(tx)

{

var safeQ = global_searchTerm;

//use placeholders (so we don't need to escape the query)

tx.executeSql(SELECT * FROM edict WHERE definition LIKE ? LIMIT + global_maxResu

ltsCount, ['%' + safeQ + '%'], successQueryDB_en_partial, errorWebSQL);

}

This is very very similar to queryDB_en(), but the important difference is in the LIKE condition.

We do not use slashes here which means we are not locked down to an exact match and will

match any definition list where the user’s search term appears. For example, searching for “user

interface” will match a definiton of:

/graphical user interface/GUI/

The success callback here is successQueryDB_en_partial() which is going to trigger the final

step [3] of English searching, or display results from this step [2].

It is in the same shape as the other success callbacks so far:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-74-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 70

//Callback for if queryDB_en_partial() did not error (which includes zero results)

//Print partial matches if we have any ELSE try romaji matches

function successQueryDB_en_partial(tx, results)

{

if(results.rows.length == 0) //no partial matches - try as romaji

{

//console.log('no en partial matches');

//version 1.0, 4 megabytes

var db = window.openDatabase(Japxlate, 1.0, Japxlate DB, 4 * 1024 * 1024);

db.transaction(queryDB_en_romaji, errorWebSQL);

}

else

{

putResultsOnPage(results);

}

}

We do step [3] - if we need to - by calling queryDB_en_romaji(). This is going to be the fiddly step

that we mentioned earlier as it will need to convert search terms like “sayonara” or “moshimoshi”

into phonetic Japanese kana so we can then search the database. queryDB_en_romaji() is like

this:

//Search edict for a romaji match

function queryDB_en_romaji(tx)

{

var safeQ = global_searchTerm;

var safeQKana = romaji_to_hira(global_searchTerm);

//use placeholders (so we don't need to escape the query)

tx.executeSql(SELECT * FROM edict WHERE kana LIKE ? LIMIT + global_maxResultsCou

nt, [safeQKana], successQueryDB_en_romaji, errorWebSQL);

}

We convert the search term into hiragana (which is one of the Japanese phonetic scripts and the

most common one used in the kana field of our table) via romaji_to_hira() which we implement

very soon. The query is straightforward, but don’t forget to implement the success callback of

successQueryDB_en_romaji() which is a carbon copy of successQueryDB_ja_kana() but with

a different name.

So we’ve come to a bit of a dead-end as we need to implement the romaji_to_hira() script

conversion function. Well, I know from the experience of building the @japxlate bot - and

Mapanese - that we can cover almost all cases of Japanese – English script conversion by

simple string replacement operations. For example, we have a table of all Japanese characters

and then a corresponding table of English spellings for those characters. Then we can convert

Japanese script to English and vice versa.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-75-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 71

JavaScript has a builtin String.replace() method, but it works by replacing the first (or all)

matching regexes in the string with the supplied replacement value. We can’t give it a list of

targets and a list of corresponding replacements. We want something a little easier to use, and

so we’re going to go deep down and dirty with some advanced JavaScript. We are going to

prototype a new method onto the String object which means we can add a new method to the

String class ONCE and it is available to any variable of type string in JavaScript! Let’s put this in

linguistics.js (we’ll get back to database querying when we’ve got the language conversion

all done and dusted). OK, code first explanations second:

//Here we use prototyping to add a method to the String class to give

//us the equivalent of PHP's str_replace()

String.prototype.str_replace = function(find, replace)

{

var replaceString = this;

var regex;

for (var i = 0; i find.length; i++) {

regex = new RegExp(find[i], g);

replaceString = replaceString.replace(regex, replace[i]);

}

return replaceString;

};

‘String’ is JavaScript’s object name for character strings. Any variable - or literal - that’s a string

will be of object type ‘String’. That’s how we can run .replace() and .match() and things

like that on any JavaScript string - because they are all String objects and the String object has

prototypes of those methods.

So the syntax to prototype a new method into the String object is:

String.prototype.newMethodName = function(any, args, you, need){code; to; do; stuff;};

We name the method “str_replace” (in honour of PHP ;-)) and define it as a function accepting

two parameters; find and replace - both of which are character arrays.

In a prototype method, the context of ‘this’ will refer to the object on which the method was

called. For example, if calling myStringVariable.str_replace(), then in the str_replace()

protoype, ‘this’ will be myStringVariable.

We save the string in replaceString. We then loop over each item in the find array and globally

(the ‘g’ modifier) replace any occurrences of it with the corresponding character in the replace

array. So yes, the find and replace arrays need to have the same number of items in them which

we don’t explicitly police here.

Before we write romaji_to_hira(), we need the character tables that our String.str_-

replace() will operate on. I won’t dwell on these too much, and it’s best to simply paste these

in to your code as a black box - this isn’t a linguistics course! Though the variable names and

comments will help if you want to read through it. Stick these at the top of linguistics.js:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-76-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 72

//----character tables----------------------------------------------------------

//All single character hiragana (in biggest first order)

var coreHiragana =

[

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '',

'', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

];

//All single character katakana (in biggest first order)

var coreKatakana =

[

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '',

'', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

'', '', '',

'', '', '', '', '',

];

//Transliterations of coreHiragana](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-77-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 73

var coreRomaji =

[

'ga', 'gi', 'gu', 'ge', 'go',

'za', 'ji', 'zu', 'ze', 'zo',

'da', 'di', 'du', 'de', 'do',

'ba', 'bi', 'bu', 'be', 'bo',

'pa', 'pi', 'pu', 'pe', 'po',

'ka', 'ki', 'ku', 'ke', 'ko',

'sa', 'shi', 'su', 'se', 'so',

'ta', 'chi', 'tsu', 'te', 'to',

'na', 'ni', 'nu', 'ne', 'no',

'ha', 'hi', 'fu', 'he', 'ho',

'ma', 'mi', 'mu', 'me', 'mo',

'ya', 'yu', 'yo',

'ra', 'ri', 'ru', 're', 'ro',

'wa', 'wi', 'we', 'wo',

'n', '', //preserve chiisai tsu

'a', 'i', 'u', 'e', 'o',

'ya', 'yu', 'yo',

'a', 'i', 'u', 'e', 'o',

];

//All combination katakana

var comboKatakana =

[

'', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '',

'', '', '', '',

'', '', '',

'', '', '',

'', '',

'', '', '',

'', '', '',

'', '', '',

'', '', '',

'', '', '',

'', '', '',

'', '', '', '',

'', '', '',

'', '', '', '',

'',

''

];

//Transliterations of comboKatakana

var comboRomaji =

[

'cha', 'chu', 'che', 'cho',

'sha', 'shu', 'she', 'sho',](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-78-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 74

'ja', 'ju', 'je', 'jo',

'kya', 'kyu', 'kyo',

'gya', 'gyu', 'gyo',

'ryu', 'ryo',

'mya', 'myu', 'myo',

'hya', 'hyu', 'hyo',

'nya', 'nyu', 'nyo',

'bya', 'byu', 'byo',

'pya', 'pyu', 'pyo',

'dya', 'dyu', 'dyo',

'fa', 'fi', 'fe', 'fo',

'wi', 'we', 'wo',

'va', 'vi', 've', 'vo',

'ti',

'di'

];

//----/end character tables-----------------------------------------------------

The “combo” tables represent larger Japanese phonics that are written with two characters. We

need to search and replace these first in order to prevent splitting any of them up by searching

and replacing single characters first.

Note that we don’t define a “comboHiragana” table because we can get that by computing

comboKatakana.str_replace(coreKatakana, coreHiragana); if we need to.

romaji_to_hira() is going to now look like this:

//Convert romaji to hiragana

function romaji_to_hira(romajiString)

{

//replace combos first

var katakana = romajiString

.str_replace(comboRomaji, comboKatakana)

.str_replace(coreRomaji, coreKatakana);

//force hiragana

return kata_to_hira(katakana);

}

We accept a string in romaji (abc) and then run String.str_replace() on it twice using a

technique called chaining. We replace combo characters first and then single characters. We

now have a converted string in katakana, but as the function name implies we want to return

hiragana. We return the katakana as modified by kata_to_hira() which we implement, again

in linguistics.js, thus:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-79-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 76

//Convert kana (hira or kata) to romaji

function kana_to_romaji(kanaString)

{

//force katakana

var kata = hira_to_kata(kanaString);

//transliterate

var withChiisaiTsu = kata.str_replace(comboKatakana, comboRomaji)

.str_replace(coreKatakana, coreRomaji);

//fix any remaining chiisai tsu's

//before 'chi' (make tchi)

var romaji = withChiisaiTsu.replace(/chi/g, 'tchi');

//before anything else (double the consonant)

romaji = romaji.replace(/([a-z]{1})/g, $1$1);

//TODO katakana style '' (which might actually be '-' in the input string)

romaji = romaji.replace(/([^0-9])[-]([^0-9])/g, $1$2);

romaji = romaji.replace(/([a-z]{1})/g, $1$1);

return romaji;

}

Again it’s best to think of this as a black box, but what it’s doing is the opposite of romaji_-

to_hira() but with some extra cleanup steps at the end. Searching for anything now has romaji

(abc) in brackets on each result line:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-81-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 82

//Touchstart event handler for search results div - initiates touch scrolling

function touchstartForSearchResults(event)

{

//console.log('touchstart');

touchobj = event.changedTouches[0]; //reference *first* touch point

startVerticalDragScrolling(this, touchobj.clientY);

event.preventDefault(); //prevent default tap behavior

}

//Touchmove event handler for search results div - performs touch scrolling

function touchmoveForSearchResults(event)

{

//console.log('touchmove');

touchobj = event.changedTouches[0]; //reference first touch point for this event

doVerticalDragScrolling(this, touchobj.clientY);

event.preventDefault();

}

Well we don’t do much in these handler functions themselves, other than call soon-to-be-written

helper functions and then preventing the default action for the touch event in question. We

bundle away scroller functionality into helper functions to keep things nice and generic which

will help us later when we go back and get scrolling working with the mouse. As the default

behaviour for dragging a finger over some text would be to select that text, we prevent this

default.

The key point here is how to use the touch event that we receive. Touch events contain a

changedTouches property which is an array of touch objects. Each touch object in the array

represents a single touch directly involved in this event. Which for touchstart means all the

fingers that hit the screen, and for touchmove means all the fingers that moved.

As we don’t need or want to do anything fancy with multi touch gestures on Japxlate, we can

simply access .changedTouches[0] and ignore the rest. There will always be at least one touch

object in changedTouches[0], and there may or may not be more.

We pass the clientY property of our touch object to our helper functions. As the first argument,

we also pass ‘this’, which if you remember for event handler functions means the element that

the event triggered on - in this case the search results div.

See http://www.javascriptkit.com/javatutors/touchevents.shtml for more about touch events in

JavaScript.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-87-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 84

this so we can work out if we actually need to scroll at all! Note that to get the height of the

results pane, we subtract the height of the search form from the total height of .japxlate_app. We

get the height of the search form by getting the height of the #search-form wrapper div which

we need to implement in index.html thus:

div id=search class=current

div id=search-form

button type=button id=search-button style=float:right; width:45%; margin-

right:1%;

img src=img/search.png

Search

img id=button-spinner src=img/spinner.gif style=visibility:hidden;

/button

input type=text id=search-query placeholder=Japanese or English size=40

style=width:45%; margin-left:1%;

br

span id=loading-text

[Loading core dictionary. This takes a while the first time.

img src=img/spinner.gif]

/span

/div

div id=results-wrapper

.

.

/div

.

.

/div

That’s the initiator, now on the the actual scroller which is, of course, going to be a bit more

complex. We need to use the global values we just saved to work out how far we’ve scrolled and

then move the results div accordingly. We also should check if we need to do any scrolling at all

- there might be no overflow of content!

A first bash looks like this:

//do vertical scrolling for ontouchmove

function doVerticalDragScrolling(elementToScroll, eventClientY)

{

//console.log('do scrolling');

//if height of results content is less than height of results pane,

//we have no content overflow and so don't need to scroll

if(global_scrollDivHeight global_scrollWindowHeight)

{

console.log('no overflow');

return;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-89-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 86

return;

}

//calculate distance travelled by touch point

var distance = parseInt(eventClientY) - global_scrollStartY;

//new CSS top for elementToScroll

var newTop = global_scrollDivTop + distance;

//disallow scrolling bottom of content higher than bottom of results pane

//(using height of results pane)

if(newTop ((0 - global_scrollDivHeight) + global_scrollWindowHeight))

{

console.log('top cushion');

return; //return false??

}

//disallow scrolling top of content lower than top of results pane

if(newTop 0)

{

console.log('bottom cushion');

return; //return false?

}

//set the new top value for the div we are moving

elementToScroll.style.top = newTop + 'px';

}

(The changes are the two if clauses before the final elementToScroll.style.top.) To stop the

top of the results going lower than the top of the results pane, we simply prevent the results

div’s top property from going higher than zero. To prevent the bottom of the results from going

higher than the bottom of the results pane, we have to prevent the top value from going less than

negative(results height + results pane height). If the height of the results is 1000 pixels, and we

set the results div top to -1000 pixels, this will put the bottom of the results right at the top of

the results pane. From this state, adding, to top, the height of the results div will put the bottom

of the results at the bottom of the results pane. This is the minimum height we enforce here.

[NOTETOSELF the height of the results div.(?)]

Run this on your device and you’ll see that scrolling is “locked” and behaves more like native

Android.

Great, just one more problem which you might already be thinking about. Run the app and search

for “it’s” which produces lots of results. Scroll right to the bottom of the results. No problems

there. But then do a search that only gives a few results like “gas”. Eh? Where are the results?

Well, when you scrolled to the bottom of the results for “it’s” you moved the top value of the

search results div to quite a high negative number. This means that the top of the div is very

high up on the page, probably higher that the top of the screen! When you search again, the

div is still up there and a short amount of content will be obscured and not “reach down” to

the visible results pane. Clearly we need to reset the search result div’s top on every display of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-91-320.jpg)

![The Search tab 88

//Mousedown event handler for search results div - initiates simulated touch scrolling

function mousedownForSearchResults(event)

{

//console.log('mousedown event on scrollable');

global_mouseButtonDown = true; //set global

startVerticalDragScrolling(this, event.clientY);

event.preventDefault(); //prevent default click behaviour (ie. select text or whate

ver)

}

//Mousemove event handler for search results div - performs simulated touch scrolling

function mousemoveForSearchResults(event)

{

//console.log('mousemove event on scrollable');

if(!global_mouseButtonDown)

{

return false; //do nothing if the mouse button isn't pressed down

//false is ok to return?

}

doVerticalDragScrolling(this, event.clientY);

event.preventDefault();

}

//Mouseup event handler for search results div

function mouseupForSearchResults(event)

{

//console.log('mouseup event on scrollable');

global_mouseButtonDown = false;

event.preventDefault(); //need?

}

We simply recycle our existing scrolling helpers. The biggest difference is we need to track if

the mouse button is down or not as we don’t want to scroll on a mousemove when the mouse

button isn’t down.

[NOTETOSELF mention using libraries for mobile touch scrolling etc]

[NOTETOSELF and the android webkit hack that you found]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-93-320.jpg)

![The Discover tab 91

Figure 36. Configuring a User timeline widget on Twitter

This tells us that we can embed the widget anywhere we want by using this code snippet:

a class=twitter-timeline href=https://twitter.com/japxlate data-widget-id=3786306

91635728384Tweets by @japxlate/a

script!function(d,s,id){var js,fjs=d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0],p=/^http:/.test(d.loc

ation)?'http':'https';if(!d.getElementById(id)){js=d.createElement(s);js.id=id;js.src=p

+://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js;fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js,fjs);}}(document,

script,twitter-wjs);/script

Which is a stylised a element followed by some arcane looking JavaScript which actually

creates, programatically, a script tag with the appropriate JavaScript from Twitter to turn the

a element into the correct widget. Clever!

Let’s go ahead and stick this in the HTML for our Discover tab and see what happens. Make the

Discover tab in index.html look like this:

div id=discover class=current

a class=twitter-timeline href=https://twitter.com/japxlate data-widget-id=378

630691635728384

Tweets by @japxlate (network connection required) img src=img/spinner.gif

/a

script!function(d,s,id){var js,fjs=d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0],p=/^http:/.test(d

.location)?'http':'https';if(!d.getElementById(id)){js=d.createElement(s);js.id=id;js.s

rc=p+://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js;fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js,fjs);}}(docume

nt,script,twitter-wjs);/script

/div](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-96-320.jpg)

![The Write tab 100

Better!

10.2 Filling the screen

Hmmm, but Android devices come in all shapes and sizes. What to do about the size of the

canvas? We would want, ideally, the biggest square (Japanese characters tend to be rather

squareish) that would fit on the screen at that time - for portrait or lanscape.

We’ll take an approach like this:

1. Put the two buttons at the bottom of the screen

2. Make a containing div for the canvas that fills 100% of its available width and height

(the height under “Write this character” and above the buttons, then the full width of the

screen)

3. Set the size of the canvas to be the biggest square that will fit in this container. Centred in

the container

4. When the device is rotated, we will have to resize the canvas to be the biggest square in

the newly created container size

OK, tackling [1] and [2] first, we need a new layout. We are going to do the same thing we did

for the app’s header, content and footer; position them absolutely relative to parent. But this time

the parent will be our .japxlate_app div. Edit the write div in index.html to look like this:

div id=write class=current

p id=write-introWrite this character: span style=font-size:2em; id=char-to-

write/span

span id=char-explanation/span

/p

div id=write-canvas-container

!--canvas id=paper width=300 height=300/canvas--

/div

div id=write-buttons

button type=button id=canvas-clear style=width:45%; margin-right:1%; floa

t:right;

img src=img/paste.png Clear

/button

button type=button id=canvas-new style=width:45%; margin-left:1%;

img src=img/file.png New character

/button

/div

/div

We’ve given the intro paragraph an id. We’ve commmented the canvas out for the time being

but we’ve put it in a container div of #write-canvas-container. The buttons have also been placed

in a containing div of #write-buttons. Now we need to position and size these elements such that

the intro paragraph will be right at the top, the buttons will be right at the bottom, and the canvas

container will fill all the space inbetween. Add these CSS rules to index.css:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-105-320.jpg)

![The Write tab 101

#write-intro {

position:absolute;

top:0; /*absolute top of .japxlate_app*/

height:40px; /*make arbitrarily big enough for our 2em character*/

width:100%;

margin-bottom:0; /*so #write-canvas-container is flush*/

margin-top:10px; /*so we aren't directly under the navigation tabs*/

text-align:center; /*centre text horizontally*/

/*background-color:green;*/

}

#write-canvas-container {

position:absolute;

top:50px; /*make flush with #write-intro*/

bottom:40px; /*stop 40px up from the botton of .japxlate_app*/

width:100%;

}

#write-buttons {

position:absolute;

bottom:0; /*absolute bottom of .japxlate_app*/

height:40px; /*make flush with bottom of #write-canvas-container*/

width:100%;

}

We simply make write-intro and write-buttons a little bit bigger than they need to be, and set

canvas container to fill the remaining space. We set margin-top of #write-intro to 10px so that

the intro paragraph text is not too close to the tabs and so that we know the top of #write-

canvas-container is 50px. We have previously set padding-top of .japxlate_app to 1em but this is

obliterated with the position:absolute and top:0 of #write-intro. (So yes, we’ve set a default

top padding of 1em on .japxlate_app but only used it in the Search tab as we positioned over it

on the Discover tab and this tab!). If you like you can confirm the size and shape of these divs

by setting a different background-color in each of the CSS rules and then changing the size of

desktop Chrome or rotating your device.

For [3] we need to programatically get the dimensions of #write-canvas-container, work out

the biggest square that will fit in those dimensions (possibly trimming a bit off so our canvas

isn’t too close to the buttons etc), and then dynamically add the appropriate canvas element into

#write-canvas-container - centreing it.

For [4] we need to catch a device rotation event and then do the steps for [3] again.

Create a file called canvas.js in assets/www/js. Include this JavaScipt file from the bottom of

index.html (above the include for index.js).

We are going to implement a function in canvas.js called adjustCanvas() which will be our

step [3]. adjustCanvas() looks like this:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-106-320.jpg)

![The Write tab 103

Wow, this is our longest piece of JavaScript so far. With the first two lines we get the container

element for the canvas, and its style. We then save the width and height of the container.

We get the smallest dimension of the container (which will be the squared size of our canvas) by

assuming the container is portrait shaped. If container height is less than container width, we say

it is landscape shaped. (A perfectly square container will be covered by the portrait assumption

which will be fine as any of its side measurements is fine to use in that case.) We then put an

imaginary frame around the canvas of 15 pixels so that the bottom of the canvas is not flush

with our buttons.

Thinking ahead to step [4], it would be nice if this function to set up the canvas initially could

also be used to adjust the canvas for a device rotate. We tackle this with the concept of “first

time”. Basically, if the function is happening for the first time - ie. the canvas does not exist -

then it must create the canvas. If not the first time then it simply needs to alter the existing

canvas. We action this by:

var firstTime = !document.getElementById('paper');

Which relies on document.getElementById('someId') returning boolean false if an element

with the id of someId does not exist on the page. So we get or create the canvas ele-

ment and set its size to the smallest dimension of the container. Minus our frame gap of

course. The first time around we have to insert the created canvas element into the DOM

(document.createElement('elementname'); creates the element in memory only) which we do

with container.appendChild(canvas);.

Go ahead and delete the line:

canvas.style.position = 'relative';

and put that in the canvas{} rule in index.css as that makes more sense.

Next, mosey on over to firstLoadForTab_Write() in japxlate.js and add a call to

adjustCanvas() thus:

function firstLoadForTab_Write()

{

console.log('first load for write tab');

adjustCanvas(); //create canvas element of correct size

global_pagesLoaded.write = true;

}

Remember firstLoadForTab_Write() is our one-off initialiser for the Write tab and so running

the app now looks like:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-108-320.jpg)

![The Write tab 104

Figure 46. canvas now fills available space

Pretty good! You can test that the canvas fills the available space by closing the page, resizing

the browser and loading the page again (desktop Chrome) or closing the app, rotating your phone,

reopening the app (device).

OK, that was actually the easy bit! Our next step is [4] and this is a bit fiddly as we need to figure

out how to detect a device rotation.

Well, the proper way is to catch the “orientationchange” event (of the window object) with a

handler. (Interestingly there is no PhoneGap API to do this.) Orientationchange will fire for

each and every orientation change of the device. And then in that handler you can use the

window.orientation property to work out the device orientation. Window.orientation will be 0

meaning portrait, 90 meaning landscape (top of phone pointing right) or -90 meaning landscape

(top of phone pointing left). These values represent the number of degrees the phone has been

rotated from the resting - or zero - position which is portrait. Android does not allow the screen

to be rotated upside-down and so there is no 180 value (phones only?).

As you would expect, our desktop Chrome browser doesn’t support the orientationchange event.

(You can try to spin your monitor around but don’t blame me if you wreck anything!). Keeping

our spirit of making the app work as an app and in the desktop Chrome, we are going to do

something a little different. (Although orientationchange is the “correct” way to do it.)

The closest thing to orientationchange on a desktop browser, and something that will also work

on our WebView browser, is the “resize” event of the window object. This event fires for every

resize - big or small - of the browser window. This includes the resize that our device will do to

the WebView when we rotate the device.

OK, let’s get the ball rolling (or should that be rotating? LOL). Stick a call to

configureCanvasRotationAdjustment(); at the bottom of receivedEvent() in index.js. We

define this function in canvas.js:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-109-320.jpg)

![The Write tab 107

//return a random (non-chiisai, non-obsolete) hiragana or katakana

//RETURNs object like {char:'', romaji:'ku', type:'hiragana'}

function getRandomKana()

{

//indices to ignore from coreHiragana:

//64,65,68,=74

//so this is indices of coreHiragana of chars that we WANT to practice

//(ie. not chiisai or obsolete):

var coreIndices =

[

0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9,

10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19,

20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29,

30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39,

40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49,

50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59,

60, 61, 62, 63, 66, 67, 69, 70, 71, 72,

73

];

//get one of above indices at random

var index = coreIndices[Math.floor(Math.random() * coreIndices.length)];

//default to hiragana...

var char = coreHiragana[index]; //use our random index

var type = 'hiragana';

//...but have a 50% chance of returning katakana

if(Math.random() 0.50)

{

char = hira_to_kata(char);

type = 'katakana';

}

//return a useful object

return {char:char, romaji:kana_to_romaji(char), type:type};

}

This again might be something that’s best ignored and treated as a black box, but basically we

cherry pick a phonetic character from coreHiragana based on some desired indices (to give us a

full size and non-obsolete character). We then convert that character into katakana 50% of the

time. We return an object with the character itself and some metadata.

Let’s use this function in doNewChar() which we define in canvas.js:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-112-320.jpg)

![The Write tab 118

//New character and Clear buttons

function configureCanvasButtons()

{

document.getElementById('canvas-clear').addEventListener('click', clearCanvas, fals

e);

document.getElementById('canvas-new').addEventListener('click', doNewChar, false);

}

And that’s it! The Clear button simply calls our existing clearCanvas() function, and the New

character button simply calls our existing doNewChar() function. Try it! The write tab is much

more fun now!

Right, the remaining matter is the important one of getting drawing to work with finger moves

on the device itself. We are happy with how it works in desktop Chrome now so let’s move

forward and think about the device. We isolated the doDrawOnCanvas() function and it is ready

to accept canvas coordinates from any event, not just mouse events.

Just like with search results scrolling, the events in question are touchstart, touchmove and

touchend. These will somewhat correlate with the mousedown, mousemove and mouseup

handlers (respectively) that we’ve just implemented.

In initialiseCanvas() in canvas.js, go ahead and insert these three lines to add our touch

event handlers. Insert them after the mouse event handlers:

//touch dragging for writing pad

global_canvasElement.addEventListener('touchstart', touchstartForCanvas, false);

global_canvasElement.addEventListener('touchmove', touchmoveForCanvas, false);

global_canvasElement.addEventListener('touchend', touchendForCanvas, false);

Great, now let’s define these handlers; again in canvas.js:

//Touchstart event handler for canvas

function touchstartForCanvas(event)

{

//console.log('touchstart event on canvas');

event.preventDefault();

}

//Touchmove event handler for canvas - draw on canvas

function touchmoveForCanvas(event)

{

var touchobj = event.changedTouches[0]; //reference first touch point for this event

//where, in canvas space, has been touched?

var x, y;

x = touchobj.offsetX;

y = touchobj.offsetY;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-123-320.jpg)

![The Write tab 120

y += obj.offsetTop;

obj = obj.offsetParent;

}

while(obj);

}

return {'x':x, 'y':y};

};

We accept a DOM element in obj. We start the x and y values - our offset - at zero. Then, if we

have an .offsetparent on obj (if not then it is body and will have no parent) we loop (at least

once) cumulatively adding .offsetLeft to x and .offsetTop to y. We loop as long as there is a parent

up the chain. We return the coordinates in a little object.

Right, with this we can go back and fix touchmoveForCanvas(). Edit touchmoveForCanvas() to

look like this:

function touchmoveForCanvas(event)

{

var touchobj = event.changedTouches[0]; //reference first touch point for this event

//where, in canvas space, has been touched?

var x, y;

var canvasOffset = getPosition(global_canvasElement); //why no offset x and y for

if it's a touch event? :-(

x = touchobj.screenX - canvasOffset.x;

y = touchobj.screenY - canvasOffset.y;

doDrawOnCanvas(x, y);

}

Run this on your device. It works!

OMG, we’ve nailed it, we’ve finished all the tabs! Crack open the beers at this point ;-)

Just two more easy things. Let’s have a splashscreen that displays while we are waiting for the

app to start. Also, we’re going to need something other than PhoneGap’s default launcher icon!

10.5 Extra credit challenges

Solutions not provided.

Easy

Prevent the current character from being displayed again when clicking the New

character button](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-125-320.jpg)

![The Write tab 121

Medium

The way we have centred the big fading character on the canvas is slightly ridiculous.

Use the canvas API to properly centre the character on the canvas [NOTETOSELF

find the good link for this]

Difficult

Technically what we are doing here for finger doodling is following the mouse or finger and,

underneath it, creating a multi-sectional line. We aren’t actually simply placing a pixel under

the mouse or finger. Now, the effect is the same so it mostly doesn’t matter, but there is a side

effect of doing it this way which is that, on the device, if you draw a very quick semi-circle, for

example, it will end up looking like this:

Figure 52. Imperfect lines can be created

Re-engineer finger doodling to use HTML5 canvas’s pixel manipulation API and see

if that solves this problem. http://beej.us/blog/data/html5s-canvas-2-pixel is a useful

reference here (though a few years old now)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonegapbydissection-150226151804-conversion-gate01/85/PhoneGap-by-Dissection-126-320.jpg)

![11. Splash screen

To kill the dragon, turn to page 84. To hide in the tunnel, keep reading. LOL that was an interactive

fiction reference, because this entire chapter is optional. Why? Well it’s about implementing a

splash screen which is a contentious issue in the world of Android apps. (It also involves fiddling

with our app’s Java sources which is a bit advanced for this book.)