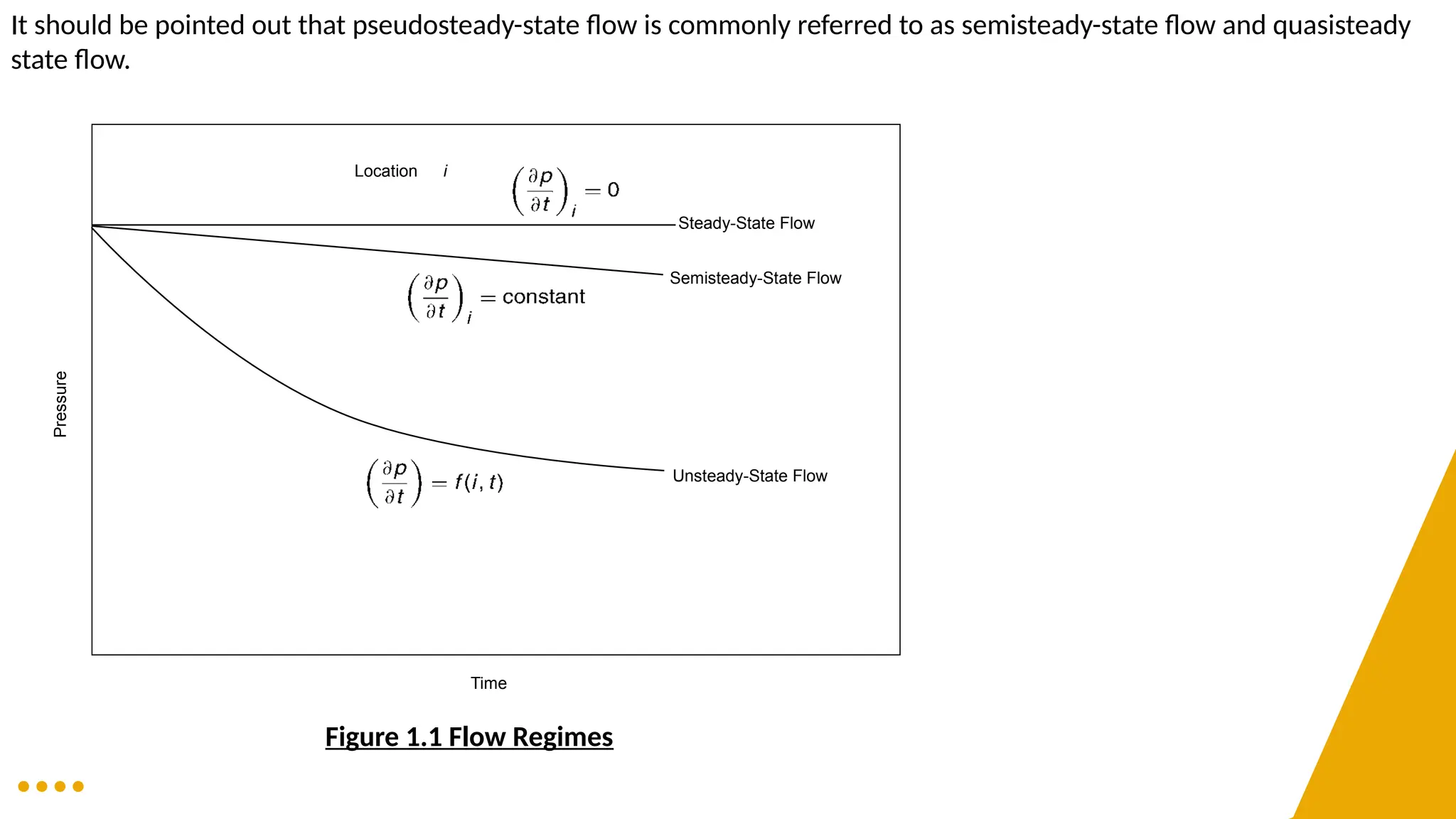

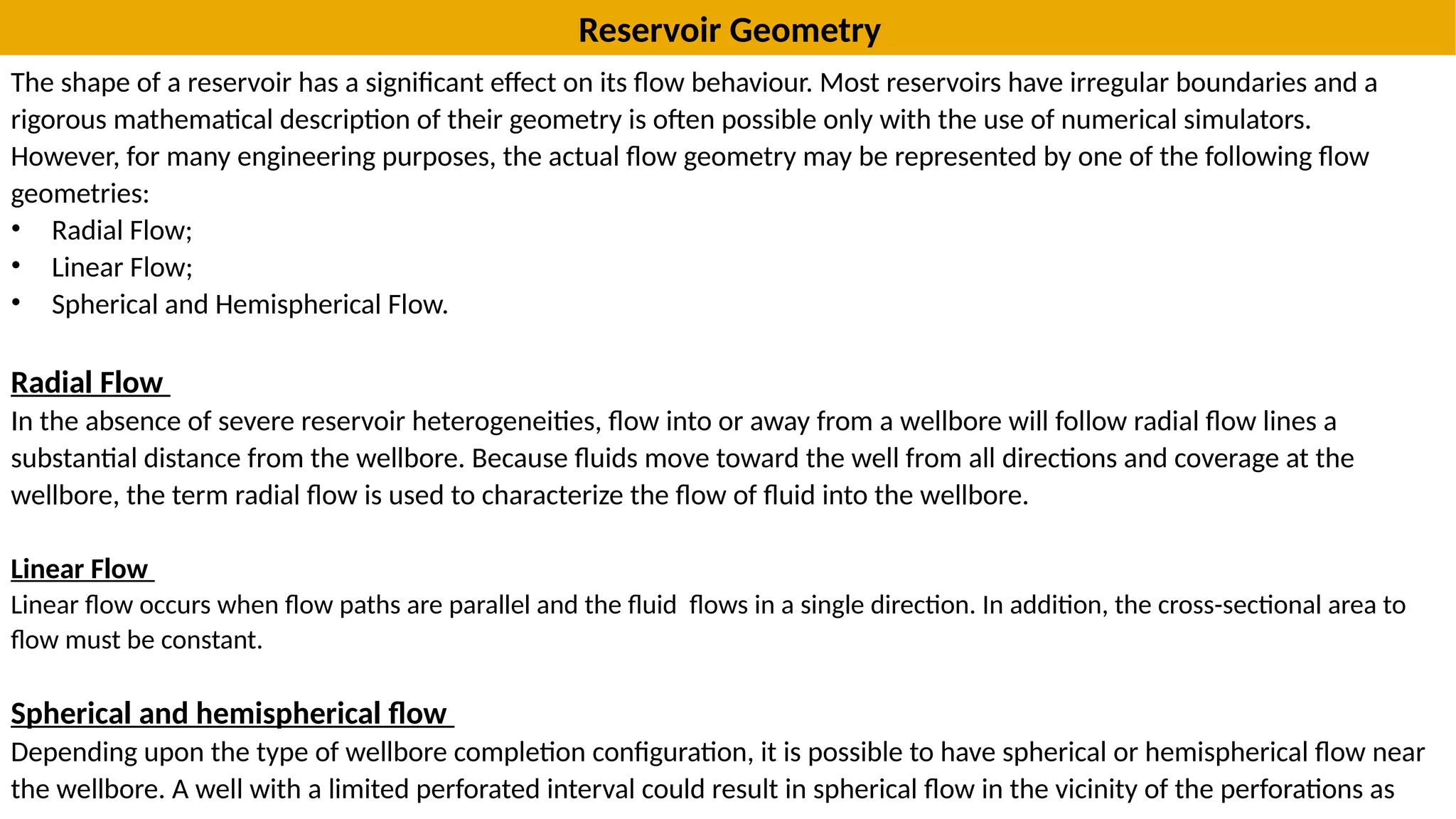

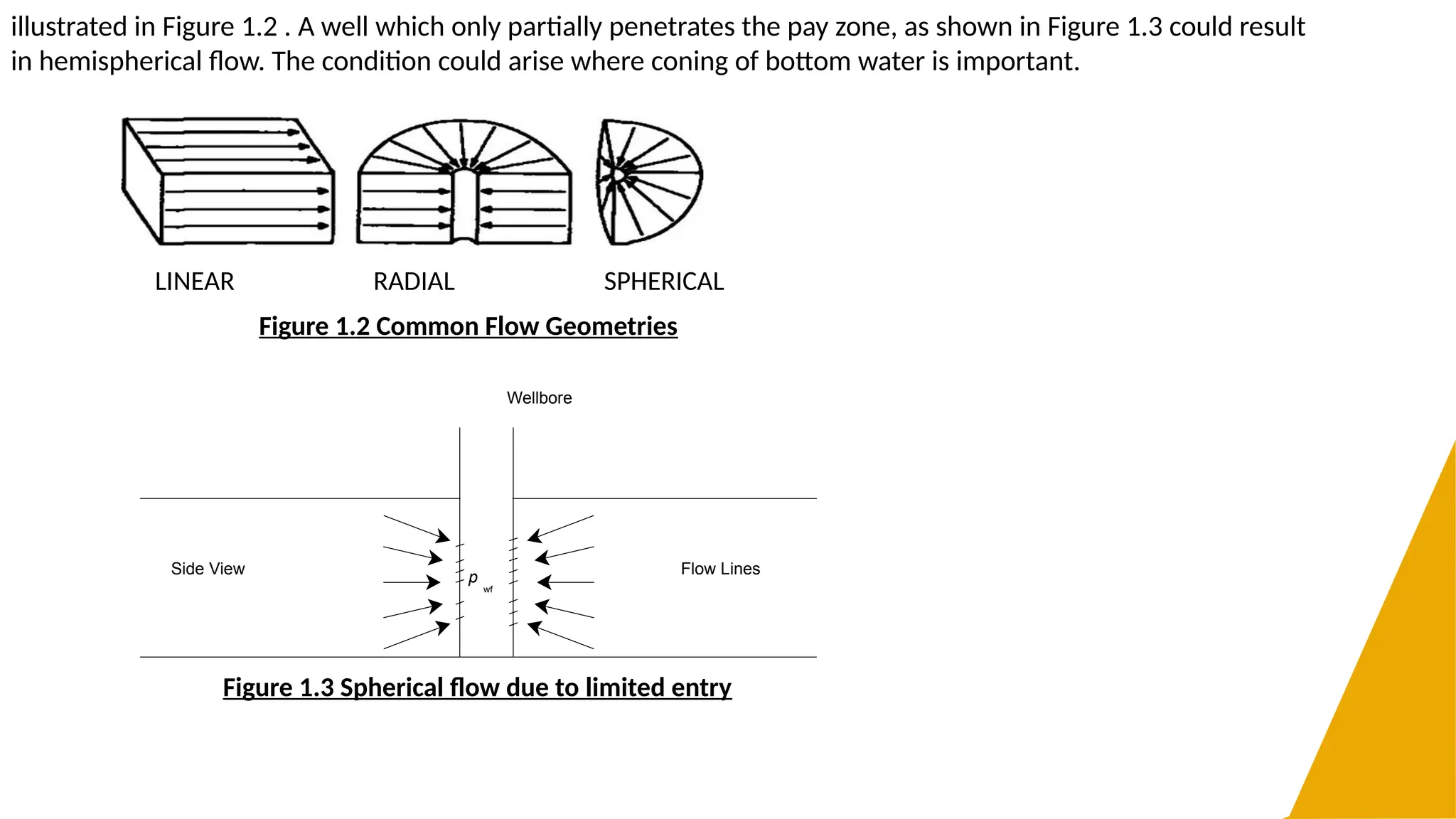

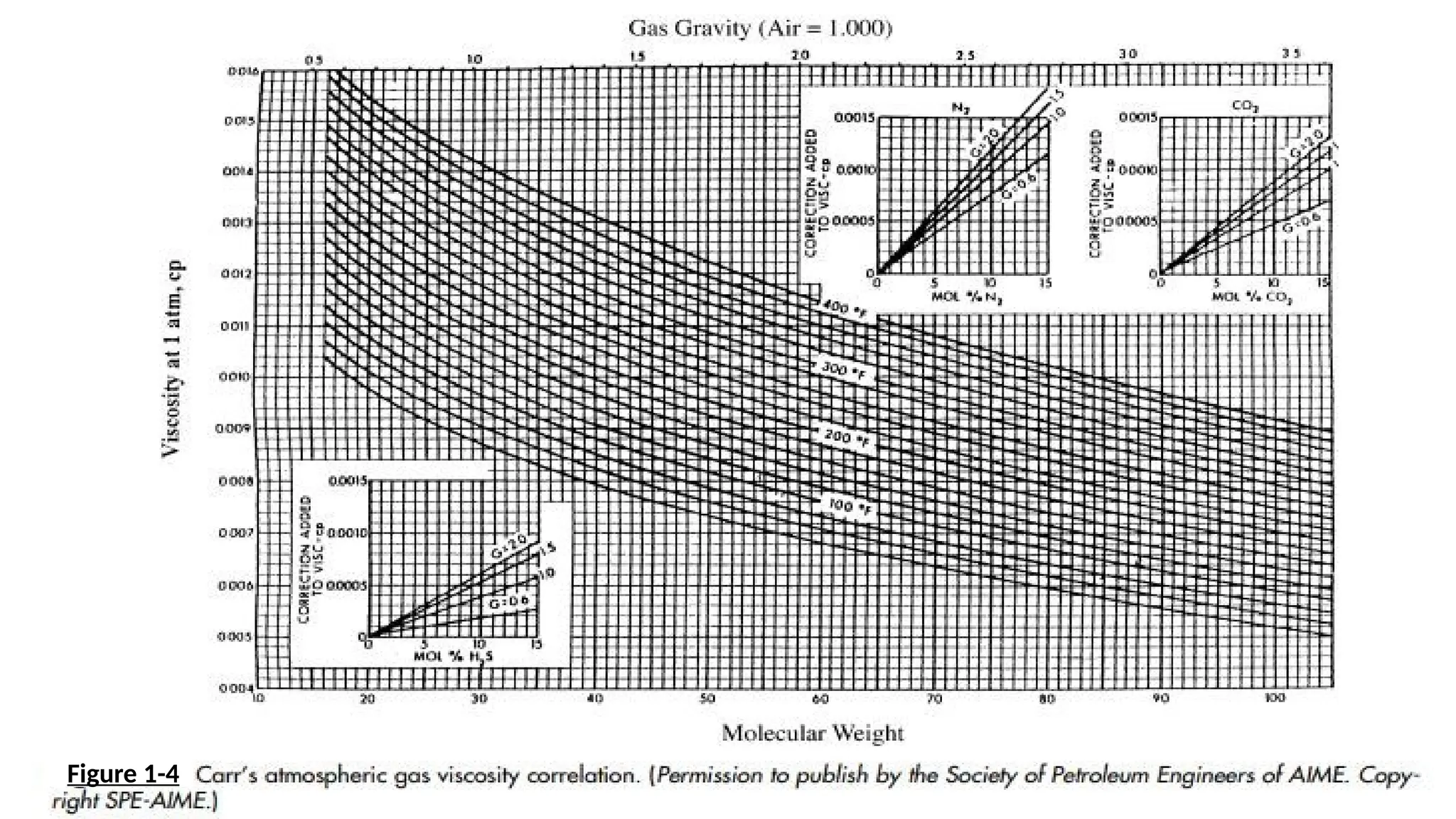

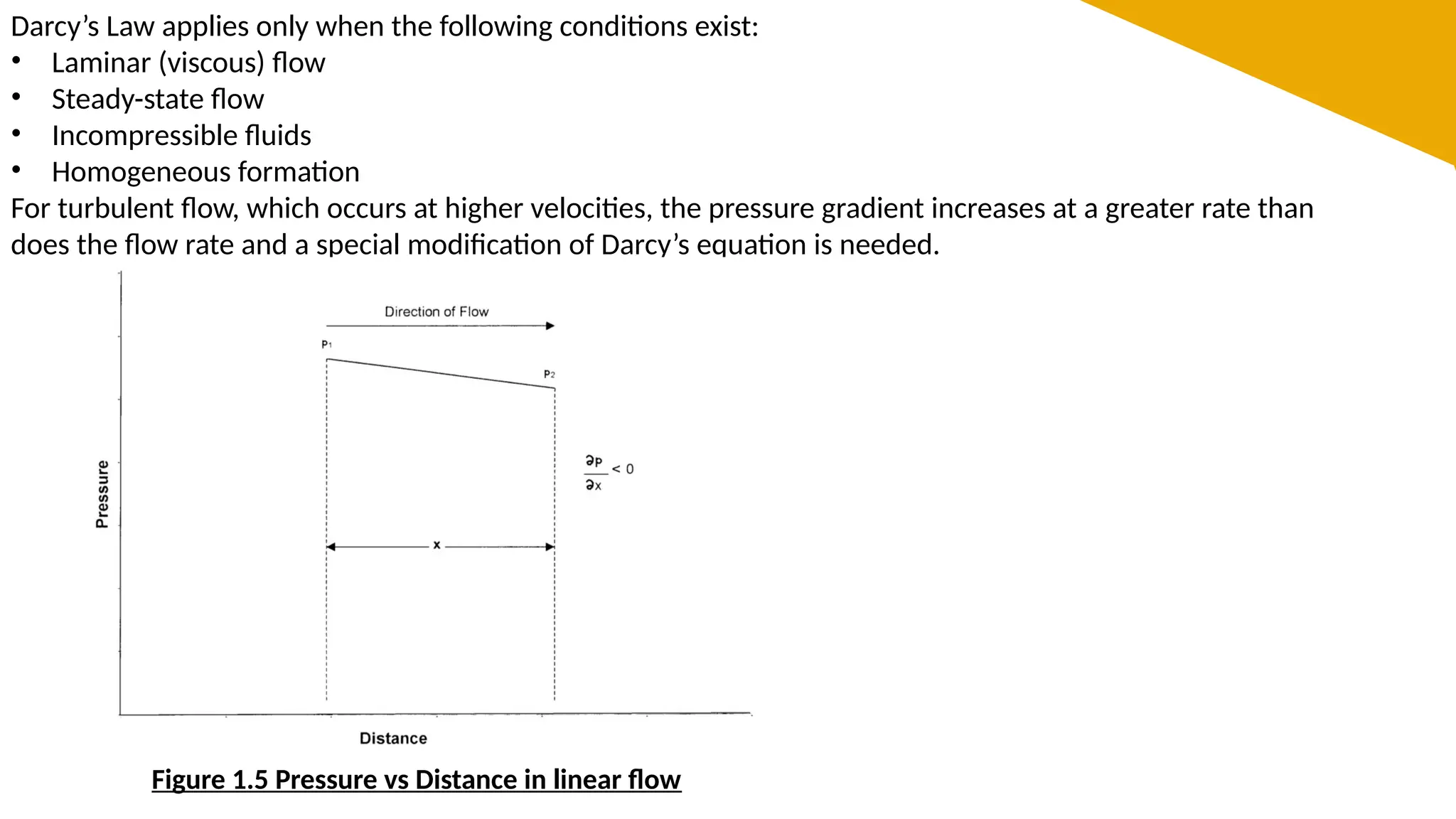

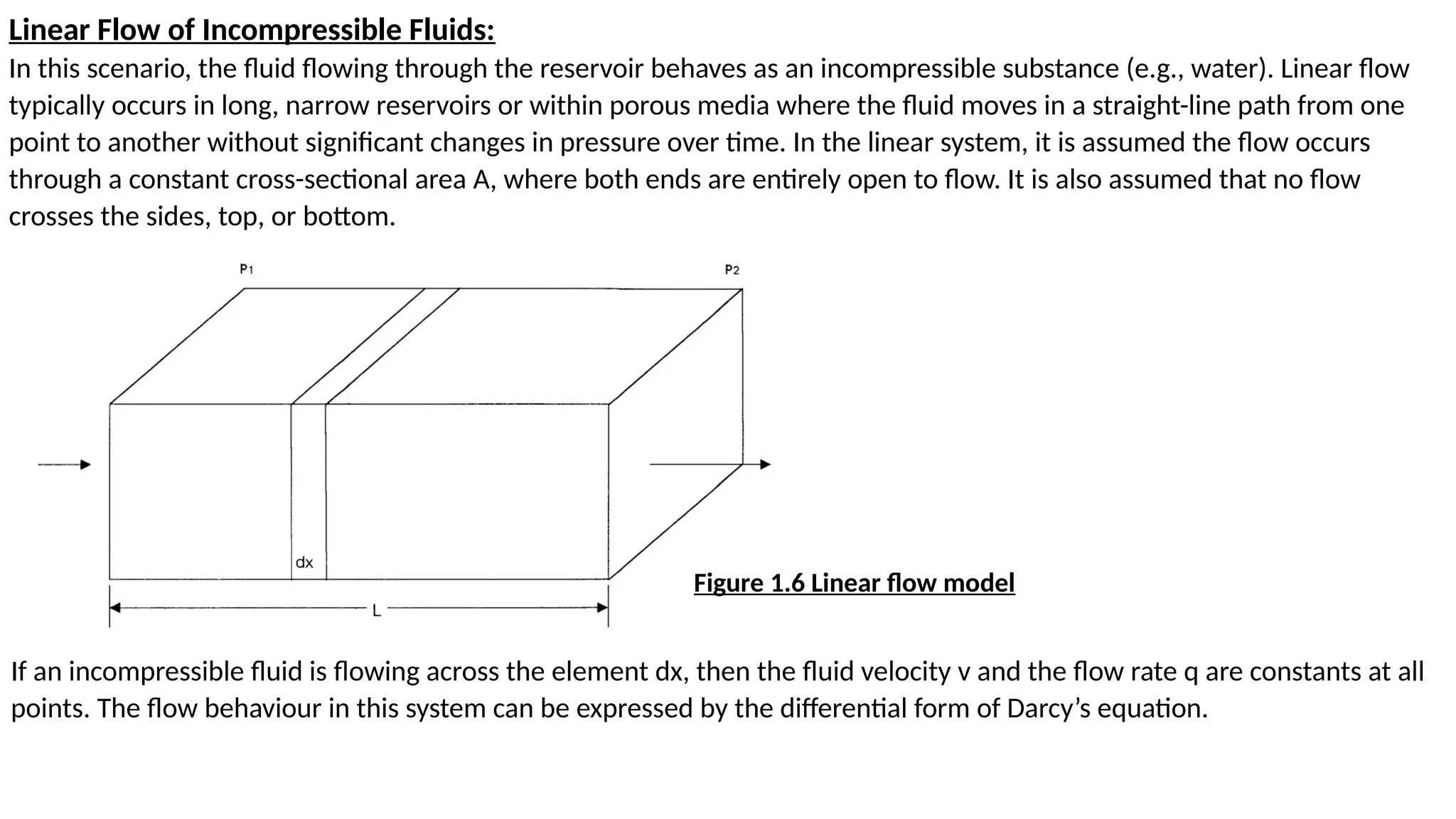

The document provides a comprehensive overview of fluid flow in porous media, structured into several key sections including types of fluids, flow equations, and properties of fluids and rocks. It explains essential concepts such as Darcy's law, flow regimes (steady-state, unsteady-state, and pseudosteady-state), and the impact of reservoir geometry on flow behavior. Additionally, it details the mathematical equations governing fluid dynamics in reservoirs, emphasizing the importance of accurately characterizing reservoir fluids for effective management and production strategies.