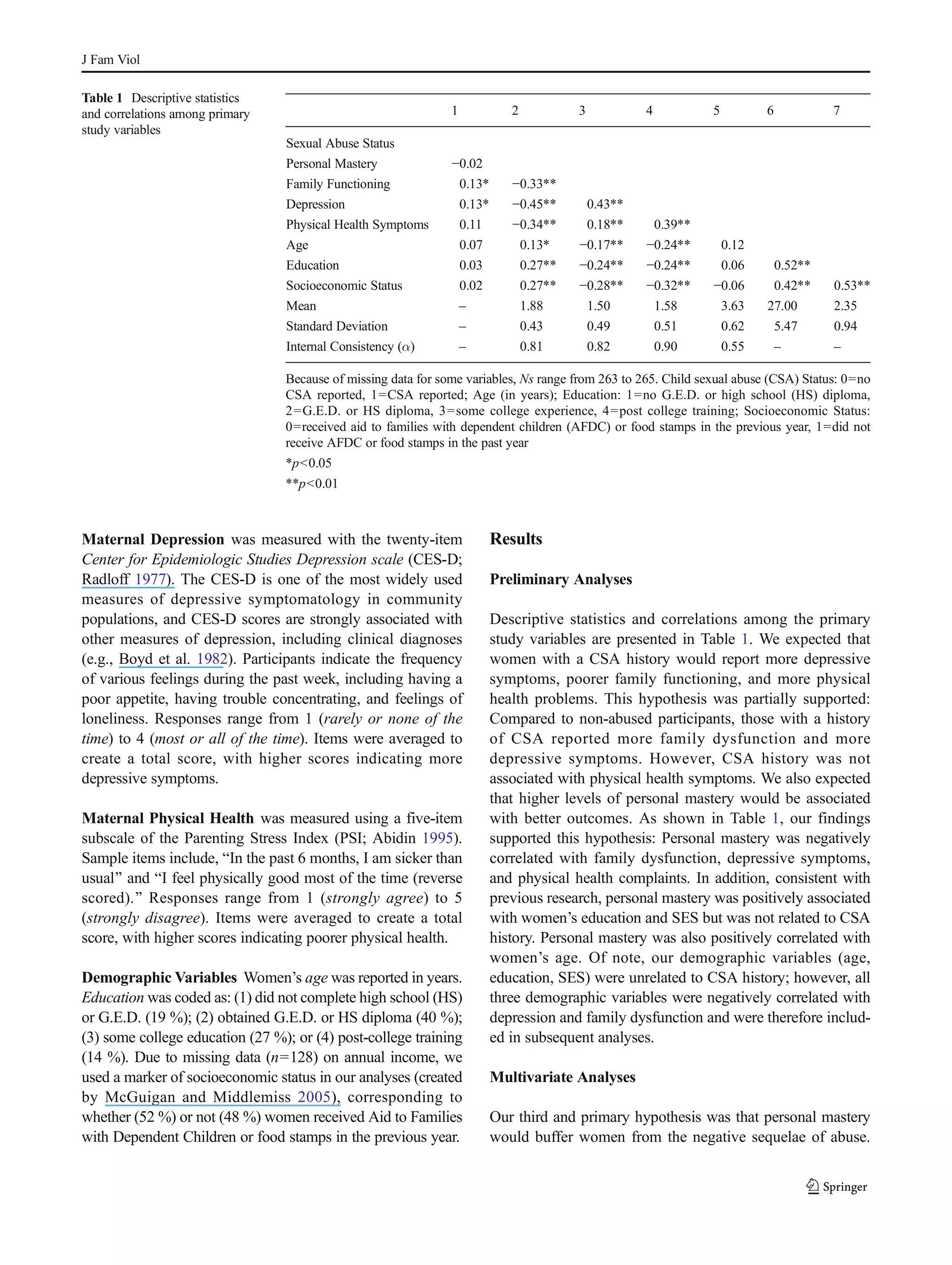

This study examined whether personal mastery buffers the negative effects of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) on women's later health and family functioning. The study found that:

1) Women with histories of CSA reported more depressive symptoms, poorer family functioning, and more physical health problems compared to women without CSA histories.

2) Higher personal mastery was associated with better outcomes in these domains for all women.

3) Personal mastery attenuated the effects of CSA on women's depressive symptoms and family dysfunction. While personal mastery was partially protective for physical health problems, the effects of CSA were still apparent.

The findings suggest that personal mastery is a coping resource that can help buffer some