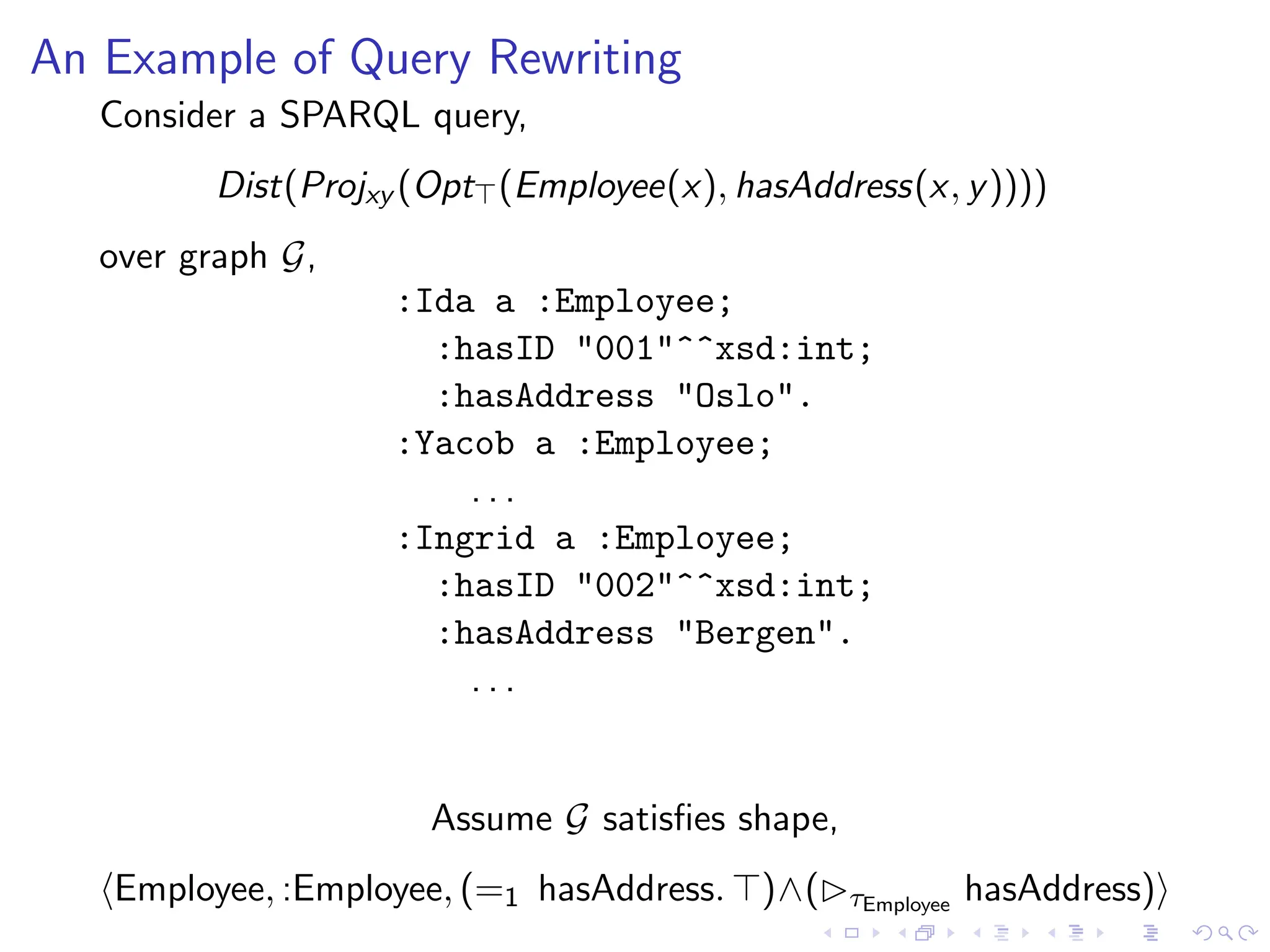

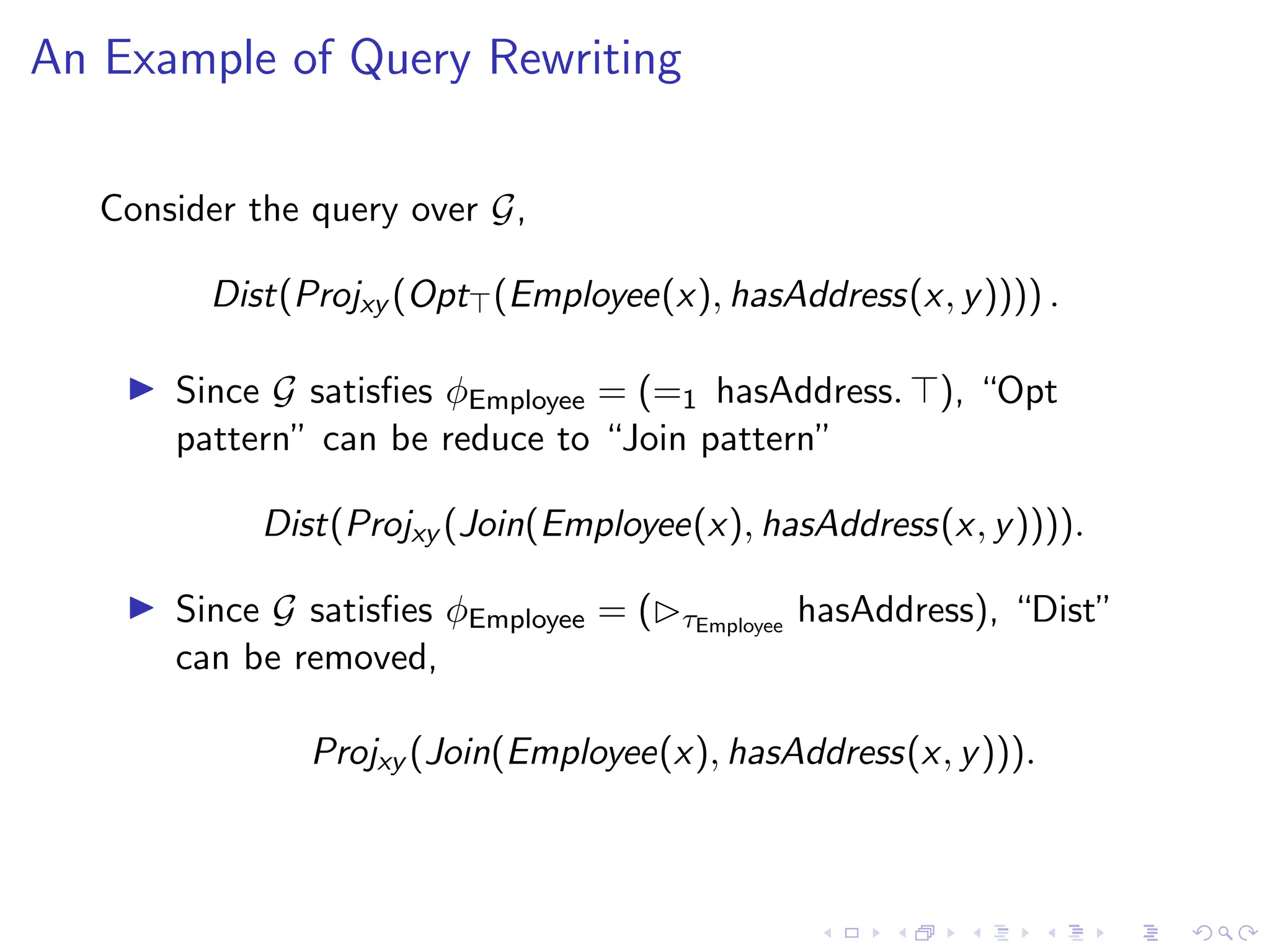

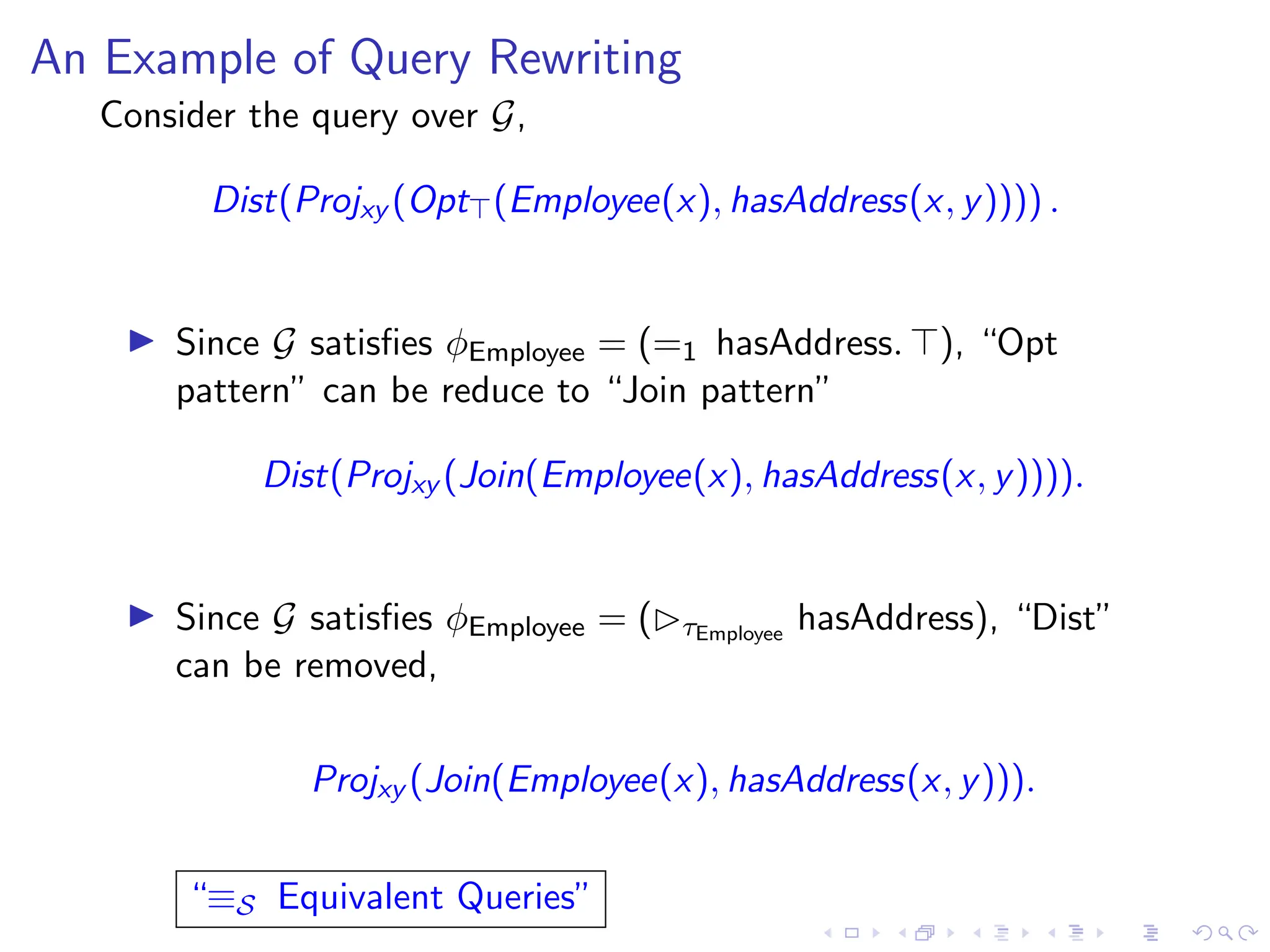

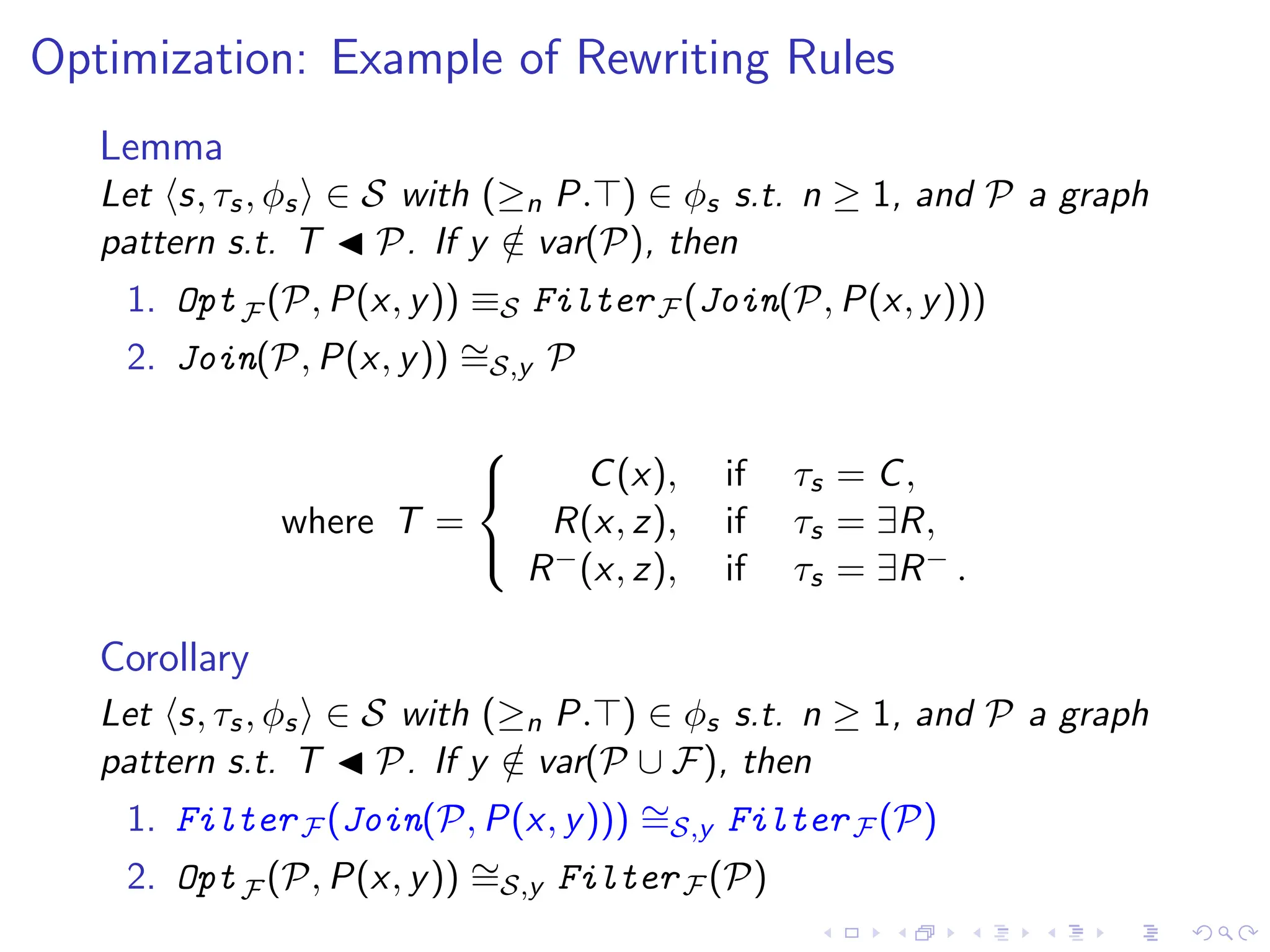

The document presents a comprehensive overview of RDF, SHACL, and SPARQL, including their syntaxes, constraints, and validation processes. It details the evolution of RDF standards and introduces SHACL as a constraint language for RDF, alongside multiple examples of its use. The document also covers query patterns, optimization techniques in SPARQL, and the grammar for querying RDF graphs.

![SHACL

▶ relies on the notion of ”shapes”

e.g.,

:EmployeeNode a sh:NodeShape;

sh:targetClass :Employee;

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

sh:nodeKind sh:Literal;

sh:maxCount 1; sh:minCount 1;

sh:datatype xsd:string ];

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

dash:uniqueValueForClass

:Employee ].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizingsparqlquerieswithshacl-231019195734-2220ad80/75/Optimizing-SPARQL-Queries-with-SHACL-pdf-9-2048.jpg)

![SHACL Shape

▶ relies on the notion of ”shapes”

e.g.,

:EmployeeNode a sh:NodeShape ;

sh:targetClass :Employee ;

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress ;

sh:nodeKind. sh:Literal ;

sh:maxCount 1;

sh:minCount 1;

sh:datatype xsd:string ];

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

dash:uniqueValueForClass

:Employeee ].

shape name

target defn

constraints

defn](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizingsparqlquerieswithshacl-231019195734-2220ad80/75/Optimizing-SPARQL-Queries-with-SHACL-pdf-10-2048.jpg)

![SHACL: Constraint Validation

Consider an RDF graph on the left and a SHACL shape on the right, written in

Turtle syntax:

:Ida a :Employee;

:hasID "001"^^xsd:int;

:hasAddress "Oslo".

:Ingrid a :Employee;

:hasID "002"^^xsd:int;

:hasAddress "Bergen".

:EmployeeNode a sh:NodeShape;

sh:targetClass :Employee;

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

sh:nodeKind sh:Literal;

sh:maxCount 1; sh:minCount 1;

sh:datatype xsd:string ];

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

dash:uniqueValueForClass

:Employee ].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizingsparqlquerieswithshacl-231019195734-2220ad80/75/Optimizing-SPARQL-Queries-with-SHACL-pdf-11-2048.jpg)

![SHACL: Constraint Validation

Acquiring Target nodes:

:Ida a :Employee;

:hasID "001"^^xsd:int;

:hasAddress "Oslo".

:Ingrid a :Employee;

:hasID "002"^^xsd:int;

:hasAddress "Bergen".

:EmployeeNode a sh:NodeShape;

sh:targetClass :Employee;

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

sh:nodeKind sh:Literal;

sh:maxCount 1; sh:minCount 1;

sh:datatype xsd:string ];

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

dash:uniqueValueForClass

:Employee ].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizingsparqlquerieswithshacl-231019195734-2220ad80/75/Optimizing-SPARQL-Queries-with-SHACL-pdf-12-2048.jpg)

![SHACL: Constraint Validation

Checking compliance of Target nodes against Constraints : VALID

:Ida a :Employee;

:hasID "001"^^xsd:int;

:hasAddress "Oslo".

:Ingrid a :Employee;

:hasID "002"^^xsd:int;

:hasAddress "Bergen".

:EmployeeNode a sh:NodeShape;

sh:targetClass :Employee;

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

sh:nodeKind sh:Literal;

sh:maxCount 1; sh:minCount 1;

sh:datatype xsd:string ];

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

dash:uniqueValueForClass

:Employee ].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizingsparqlquerieswithshacl-231019195734-2220ad80/75/Optimizing-SPARQL-Queries-with-SHACL-pdf-13-2048.jpg)

![SHACL: Propagated Constraint Validation

:EmployeeNode a sh:NodeShape;

sh:targetClass :Employee;

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

sh:nodeKind sh:Literal;

sh:maxCount 1; sh:minCount 1;

sh:node :AddressNode ].

:AddressNode a sh:NodeShape;

sh:property [ sh:path :telephone;

sh:maxCount 1; ];

sh:property [ sh:path :locatedIn;

sh:maxCount 1; sh:minCount 1;

sh:value :NorthernNorway; ];](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizingsparqlquerieswithshacl-231019195734-2220ad80/75/Optimizing-SPARQL-Queries-with-SHACL-pdf-14-2048.jpg)

![SHACL: Propagated Constraint - ”Recursion”?

:EmployeeNode a sh:NodeShape;

sh:targetClass :Employee;

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

sh:nodeKind sh:Literal;

sh:maxCount 1; sh:minCount 1;

sh:node :AddressNode ];

sh:property [ sh:path :knows;

sh:minCount 1;

sh:node :EmployeeNode ].

:AddressNode a sh:NodeShape;

sh:property [ sh:path :telephone;

sh:maxCount 1; ];

sh:property [ sh:path :locatedIn;

sh:maxCount 1; sh:minCount 1;

sh:value :NorthernNorway; ].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizingsparqlquerieswithshacl-231019195734-2220ad80/75/Optimizing-SPARQL-Queries-with-SHACL-pdf-15-2048.jpg)

![SHACL: Propagated Constraint - ”Recursion”?

:EmployeeNode a sh:NodeShape;

sh:targetClass :Employee;

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

sh:nodeKind sh:Literal;

sh:maxCount 1; sh:minCount 1;

sh:node :AddressNode ];

sh:property [ sh:path :knows;

sh:minCount 1;

sh:node :EmployeeNode ].

:AddressNode a sh:NodeShape;

sh:property [ sh:path :telephone;

sh:maxCount 1; ];

sh:property [ sh:path :locatedIn;

sh:maxCount 1; sh:minCount 1;

sh:value :NorthernNorway; ].

From : https://www.w3.org/TR/shacl/

Recursion

Not 100% formal semantics

Validation explicitly left undefined](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizingsparqlquerieswithshacl-231019195734-2220ad80/75/Optimizing-SPARQL-Queries-with-SHACL-pdf-16-2048.jpg)

![SHACL: Propagated Constraint - ”Recursion”

:EmployeeNode a sh:NodeShape;

sh:targetClass :Employee;

sh:property [ sh:path :hasAddress;

sh:nodeKind sh:Literal;

sh:maxCount 1; sh:minCount 1;

sh:node :AddressNode ];

sh:property [ sh:path :knows;

sh:minCount 1;

sh:node :EmployeeNode ].

:AddressNode a sh:NodeShape;

sh:property [ sh:path :telephone;

sh:maxCount 1; ];

sh:property [ sh:path :locatedIn;

sh:maxCount 1; sh:minCount 1;

sh:value :NorthernNorway; ].

Contributions:

Abstract syntax of SHACL core

Semantics for recursive SHACL

Validation algorithms and Tractable fragments](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizingsparqlquerieswithshacl-231019195734-2220ad80/75/Optimizing-SPARQL-Queries-with-SHACL-pdf-17-2048.jpg)