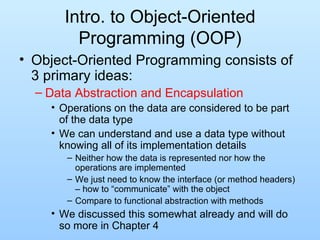

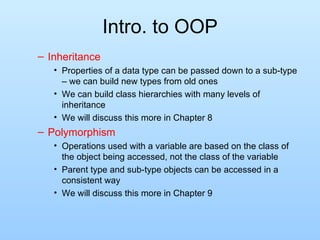

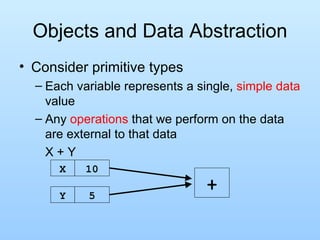

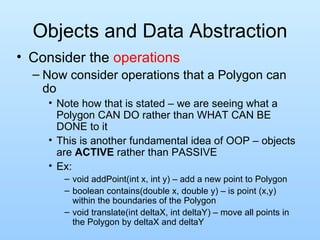

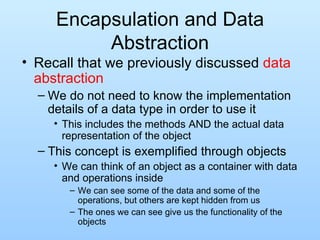

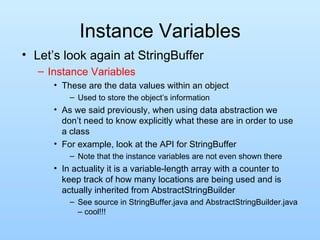

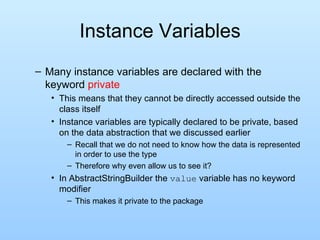

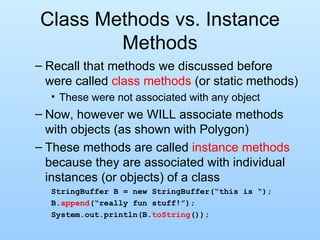

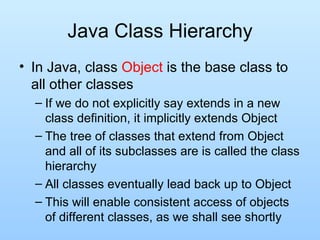

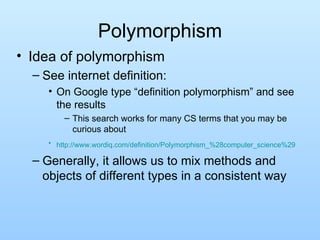

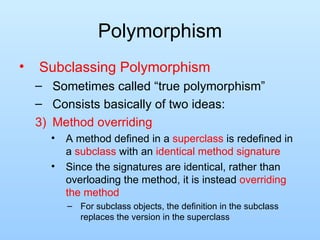

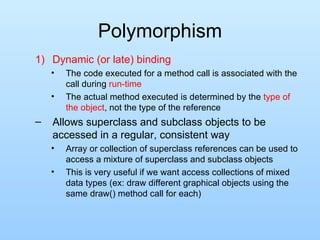

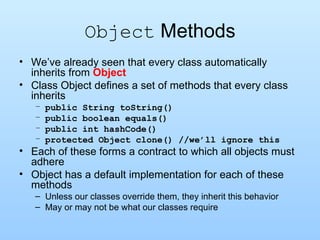

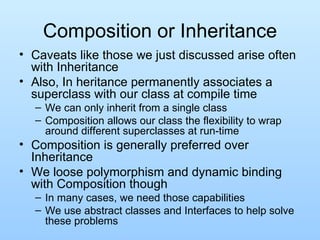

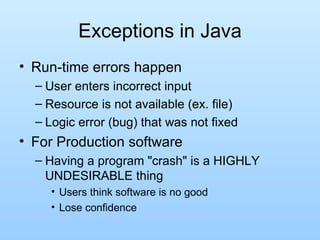

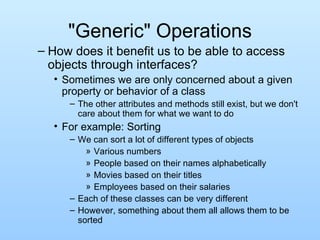

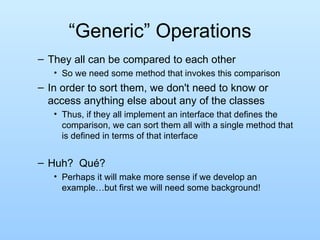

The document discusses object-oriented programming concepts in Java including data abstraction, encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism. It provides examples of how these concepts are implemented in Java by defining classes, objects, methods, and relationships between classes. Key ideas covered include using classes to represent complex data types, hiding implementation details through encapsulation, building new classes from existing ones through inheritance, and allowing uniform access to objects via polymorphism.

![Objects and Data Abstraction Consider the data In many applications, data is more complicated than just a simple value Ex: A Polygon – a sequence of connected points The data here are actually: int [] xpoints – an array of x-coordinates int [] ypoints – an array of y-coordinates int npoints – the number of points actually in the Polygon Note that individually the data are just ints However, together they make up a Polygon This is fundamental to object-oriented programming (OOP)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-5-320.jpg)

![Objects and Data Abstraction These operations are actually (logically) PART of the Polygon itself int [] theXs = {0, 4, 4}; int [] theYs = {0, 0, 2}; int num = 2; Polygon P = new Polygon(theXs, theYs, num); P.addPoint(0, 2); if ( P.contains(2, 1) ) System.out.println(“Inside P”); else System.out.println(“Outside P”); P.translate(2, 3); We are not passing the Polygon as an argument, we are calling the methods FROM the Polygon](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-7-320.jpg)

![Objects and Data Abstraction Objects enable us to combine the data and operations of a type together into a single entity P xpoints [0,4,4,0] ypoints [0,0,2,2] npoints 4 addPoint() contains() translate() Thus, the operations are always implicitly acting on the object’s data Ex: translate means translate the points that make up P](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-8-320.jpg)

![Objects and Data Abstraction For multiple objects of the same class, the operations act on the object specified int [] moreXs = {8, 11, 8}; int [] moreYs = {0, 2, 4}; Polygon P2 = new Polygon(moreXs, moreYs, 3); P xpoints [0,4,4,0] ypoints [0,0,2,2] npoints 4 addPoint() contains() translate() P2 xpoints [8,11,8]] ypoints [0,2,4] npoints 3 addPoint() contains() translate()](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-9-320.jpg)

![Encapsulation and Data Abstraction As long as we know the method names, params and how to use them, we don’t need to know how the actual data is stored Note that I can use a Polygon without knowing how the data is stored OR how the methods are implemented I know it has points but I don’t know how they are stored Data Abstraction! P xpoints [0,4,4,0] ypoints [0,0,2,2] npoints 4 addPoint() contains() translate()](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-11-320.jpg)

![Polymorphism Ex. Each subclass overrides the move() method in its own way Animal [] A = new Animal[3]; A[0] = new Bird(); A[1] = new Person(); A[2] = new Fish(); for (int i = 0; i < A.length; i++) A[i].move(); Animal move() move() move() References are all the same, but objects are not Method invoked is that associated with the OBJECT, NOT with the reference](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-55-320.jpg)

![toString() toString() returns a string representation of the object The string “should be a concise but informative representation that is easy for a person to read RULE: All classes should override this method Default implementation from the Object class constructs a string like: [email_address] Name of the class, ‘@’ character, followed by the HashCode for the class](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-60-320.jpg)

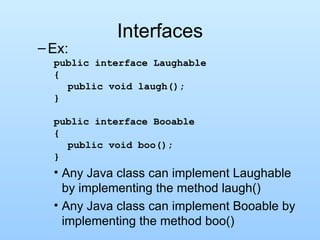

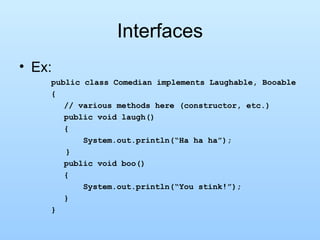

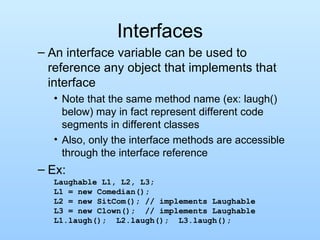

![Interfaces Polymorphism and Dynamic Binding also apply to interfaces the interface acts as a superclass and the implementing classes implement the actual methods however they want An interface variable can be used to reference any object that implements that interface However, only the interface methods are accessible through the interface reference Recall our previous example: Laughable [] funny = new Laughable[3]; funny[0] = new Comedian(); funny[1] = new SitCom(); // implements Laughable funny[2] = new Clown(); // implements Laughable for (int i = 0; i < funny.length; i++) funny[i].laugh(); See ex24.java](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-84-320.jpg)

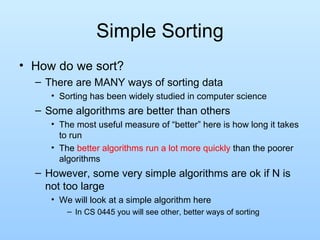

![Simple Sorting What does it mean to sort our data? Consider an array, A of N items: A[0], A[1], A[2], …, A[N-1] A is sorted in ascending order if A[i] < A[j] for all i < j A is sorted in descending order if A[i] > A[j] for all i < j Q: What if we want non-decreasing or non-increasing order? What does it mean and how do we change the definitions?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-87-320.jpg)

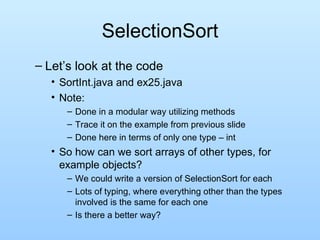

![Comparable Interface Consider the Comparable interface: It contains one method: int compareTo(Object r); Returns a negative number if the current object is less than r, 0 if the current object equals r and a positive number if the current object is greater than r Look at Comparable in the API Not has restrictive as equals() – can throw ClassCastException Consider what we need to know to sort data: is A[i] less than, equal to or greater than A[j] Thus, we can sort Comparable data without knowing anything else about it Awesome! Polymorphism allows this to work](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-91-320.jpg)

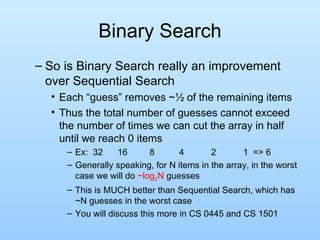

![Binary Search Idea of Binary Search : Searching for a given key, K Guess middle item, A[mid] in array If A[mid] == K, we found it and are done If A[mid] < K then K must be on right side of the array If A[mid] > K then K must be on left side of the array Either way, we eliminate ~1/2 of the remaining items with one guess Search for 40 below 75 60 50 40 35 20 15 10 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-94-320.jpg)

![HashSet Imagine implementing a Set with an array To maintain the constraint that the Set doesn’t contain duplicates, we’d have to do something like: for(int i = 0; i < count; i++) if(array[i].equals(newElement)) return; //don’t add new element array[count++] = newElement; We have to check each item before knowing if a duplicate existed in the array What if we could know the index where a duplicate would be stored if it was in the Set? Just check the element(s) at that index with equals() Add the new Element if not there This is how a Hashtable works Uses newElement.hashCode() to find index Notice the need for the contract of equals() and hashCode() Why?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-105-320.jpg)

![Generic Methods Suppose we want to write a method copies an array into a Collection: public void fromAtoC(Object[] a, Collection<?> c) { for(Object o : a) c.add(o);} We’ve already learned that we can’t do this with the wildcard We can use generic methods public <T> void fromAtoC(T[] a, Collection<T> c) { for(T o : a) c.add(o);} All the same wildcard rules apply public <T> listCopy(List<? extends T> source, List<T> dest){} When to use: Notice the dependency between the types in the parameters If the dependency does not exist, you should use wildcards instead Also used if the return type of the method is type dependent See again SortingT.java, ex26T.java, and also ex32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/oop-120226110411-phpapp02/85/OOP-Principles-124-320.jpg)