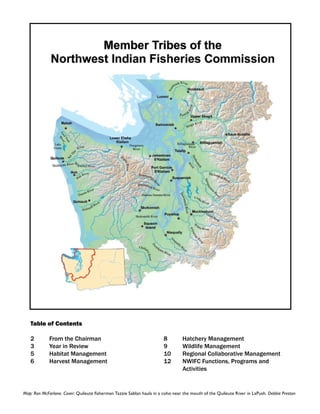

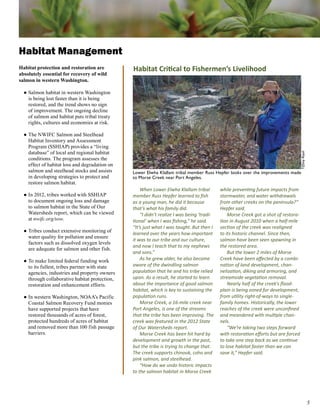

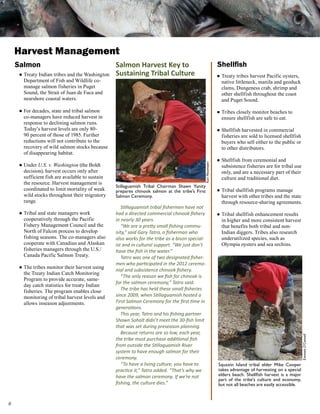

This document provides a 3-page summary of tribal natural resource management in Western Washington in 2013. It discusses several key issues, including ongoing degradation of salmon habitat, threats from climate change, and budget cuts that could impact hatchery production. It highlights tribal efforts to implement the Treaty Rights at Risk initiative to address salmon declines, and the release of the State of Our Watersheds report confirming ongoing habitat loss. It also discusses ongoing co-management of shellfish resources and tribal responses to issues like updating the state's fish consumption rate and the potential impacts of the state's budget deficit on natural resource management responsibilities.