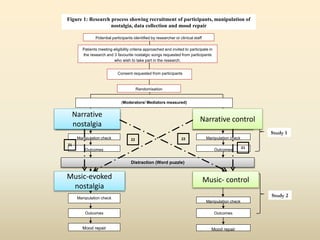

The document explores the psychological impacts of nostalgia on individuals with dementia, highlighting its potential benefits compared to non-nostalgic memories. It describes a study aimed at evaluating how nostalgic memories can address issues like self-esteem, social connectedness, and meaning in life among dementia patients. The study employs a systematic review and experimental approach to assess the effectiveness of nostalgia in counteracting the existential challenges posed by dementia.

![References

Alzheimer’s Society (2014) Dementia 2014: Opportunity for change . Available from: http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/dementia2014 [Accessed 29 November 2013].

Batcho, K.I. (2007) Nostalgia and the emotional tone and content of song lyrics. The American Journal of Psychology [online]. pp.361-381 [04 November 2013].

Cheston, R. (2011) Using Terror Management Theory to understand the existential threat of dementia. PSIGE Newsletter [online] 118, pp. 7-15. Available from:

http://www.psige.org/public/files/newsletters/PSIGE_118_web.pdf [Accessed 13 May 2013].

Coleman, P.G. (2005) Uses of reminiscence: Functions and benefits. [online] [Accessed 19 December 2013].

Eustache, M.-., Laisney, M., Juskenaite, A., Letortu, O., Platel, H., Eustache, F. and Desgranges, B. (2013) Sense of identity in advanced Alzheimer’s dementia: A cognitive dissociation between sameness and

selfhood? Consciousness and Cognition [online]. 22 (4), pp.1456-1467 [Accessed 15 January 2014].

Forsman, A.K., Schierenbeck, I. and Wahlbeck, K. (2011) Psychosocial interventions for the prevention of depression in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Aging and Health

[online]. 23 (3), pp.387-416 [Accessed 08 January 2014].

Gudex, C., Horsted, C., Jensen, A.M., Kjer, M. and Sørensen, J. (2010) Consequences from use of reminiscence-a randomised intervention study in ten Danish nursing homes. BMC Geriatrics [online]. 10 (1),

pp.33 [Accessed 12 April 2014].

Hatch, D.J. (2013) The Influence of Widowhood and Sociodemographic Moderators on Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease Risk. [online] [Accessed 11 January 2014].

Lingler, J.H., Nightingale, M.C., Erlen, J.A., Kane, A.L., Reynolds, C.F.,3rd, Schulz, R. and DeKosky, S.T. (2006) Making sense of mild cognitive impairment: a qualitative exploration of the patient's experience.

The Gerontologist [online]. 46 (6), pp.791-800 [Accessed 15 January 2014].

Macquarrie, C.R. (2005) Experiences in early stage Alzheimer's disease: understanding the paradox of acceptance and denial. Aging & Mental Health [online]. 9 (5), pp.430-441[Accessed 14 January 2014].

McGovern, J. (2012) Couplehood and the Phenomenology of Meaning for Older Couples Living with Dementia [online] [Accessed 20 November 2014].

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. and Altman, D.G. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine [online]. 151 (4), pp.264-

269 [Accessed 15 January 2014].

Moos, I. and Bjorn, A. (2006) Use of the life story in the institutional care of people with dementia: A review of intervention studies. Ageing & Society [online]. 26 (3), pp.431-454 [Accessed 10 December

2014].

Piiparinen, R. and Whitlatch, C.J. (2011) Existential loss as a determinant to well-being in the dementia caregiving dyad: A conceptual model. Dementia [online]. 10 (2), pp.185-201[Accessed 28 December

2013]

Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T. and Baden, D. (2004) Conceptual Issues and Existential Functions. Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology [online]. pp.205 [Accessed 31October 2013].

Steeman, E., Casterlé, D., Dierckx, B., Godderis, J. and Grypdonck, M. (2006) Living with early‐stage dementia: a review of qualitative studies. Journal of Advanced Nursing [online]. 54 (6), pp.722-738

[Accessed 17 November 2013].

Steeman, E., Tournoy, J., Grypdonck, M., Godderis, J. and DE CASTERLÉ, B.D. (2013) Managing identity in early-stage dementia: maintaining a sense of being valued. Ageing & Society [online]. 33 pp.216-242

[Accessed 14 November 2013].

Stephens, A., Cheston, R. and Gleeson, K. (2013) An exploration into the relationships people with dementia have with physical objects: an ethnographic study. Dementia (London, England) [online]. 12 (6),

pp.697-712 [Accessed 08 October 2013].

Van Assche, L., Luyten, P., Bruffaerts, R., Persoons, P., van de Ven, L. and Vandenbulcke, M. (2013) Attachment in old age: Theoretical assumptions, empirical findings and implications for clinical practice.

Clinical Psychology Review [online]. 33 (1), pp.67-81[Accessed 12 November 2013].

van Tilburg, W.A., Igou, E.R. and Sedikides, C. (2013) In search of meaningfulness: Nostalgia as an antidote to boredom. Emotion [online]. 13 (3), pp.450. [Accessed 10 November 2013].

Wang, J., Hsu, Y. and Cheng, S. (2005) The effects of reminiscence in promoting mental health of Taiwanese elderly. International Journal of Nursing Studies [online]. 42 (1), pp.31-36 [Accessed 25 October

2013].

Wang, J., Yen, M. and OuYang, W. (2009) Group reminiscence intervention in Taiwanese elders with dementia. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics [online]. 49 (2), pp.227-232 [Accessed 25 October

2014].

Woods, B., Spector, A., Jones, C., Orrell, M. and Davies, S. (2005) Reminiscence therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [online]. 2 [Accessed 25 October 2013].

Woods, R.T., Bruce, E., Edwards, R., Elvish, R., Hoare, Z., Hounsome, B., Keady, J., Moniz-Cook, E., Orgeta, V. and Orrell, M. (2012) REMCARE: reminiscence groups for people with dementia and their family

caregivers–effectiveness and cost-effectiveness pragmatic multicentre randomised trial. Health Technology Assessment [online]. 16 (48), pp.1366-5278 [Accessed 25 October 2013].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nospsychdempostgradpsychconf-140926050208-phpapp01/85/The-psychological-impacts-of-nostalgia-for-people-with-dementia-22-320.jpg)