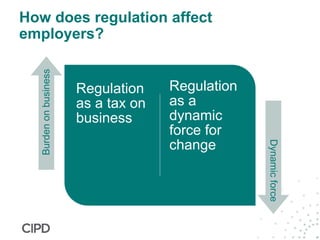

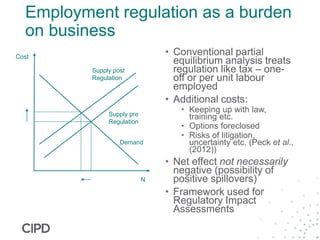

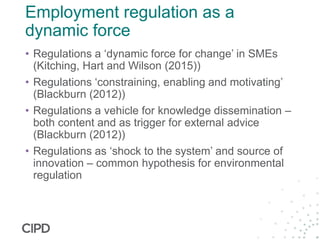

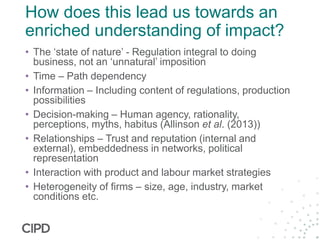

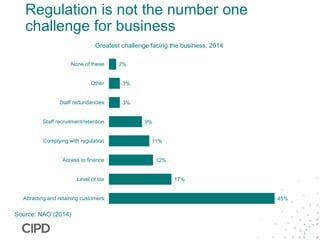

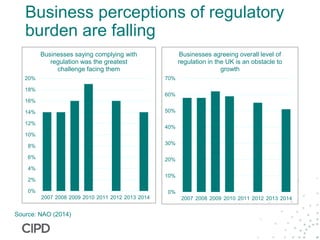

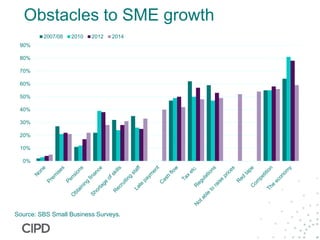

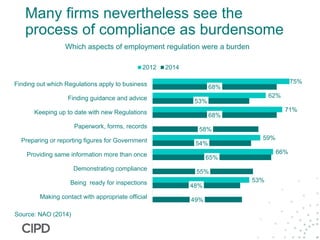

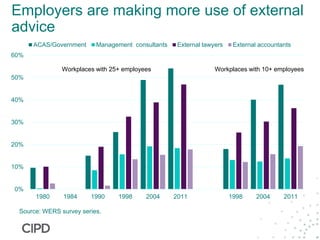

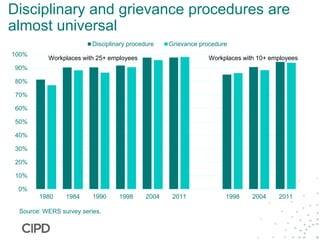

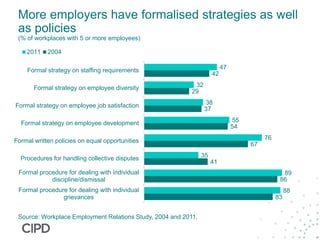

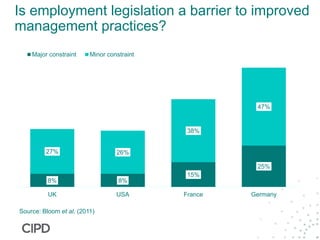

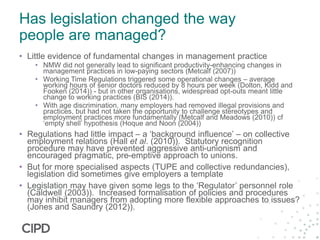

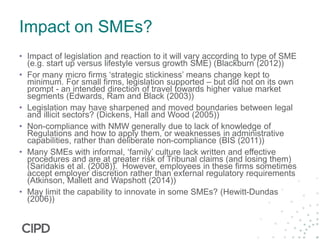

Regulation affects employers in complex ways. It can burden businesses by increasing costs but can also act as a dynamic force that enables innovation. While regulations may increase compliance costs for firms, these costs are now relatively modest compared to other challenges firms face like attracting customers. Additionally, businesses' perceptions of regulatory burdens have been falling in recent years. Overall, employment regulations have had limited impact on fundamentally changing management practices in firms, though they have increased formalization of policies and procedures to some degree. The impact of regulations varies for different sized firms, especially between large firms and small- and medium-sized enterprises.