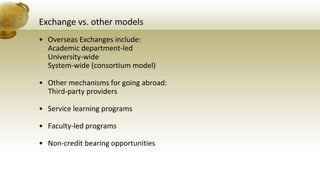

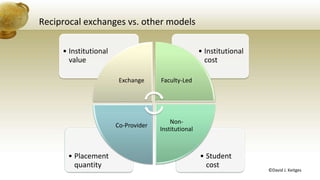

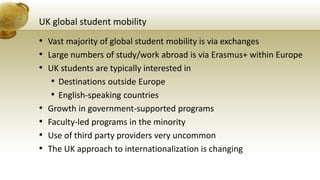

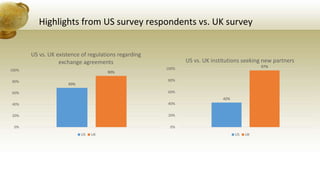

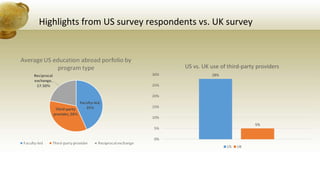

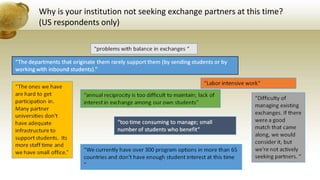

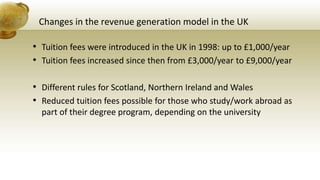

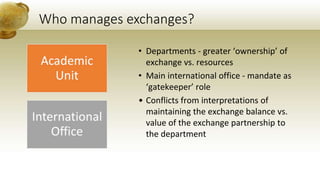

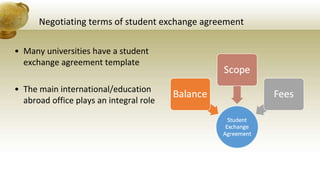

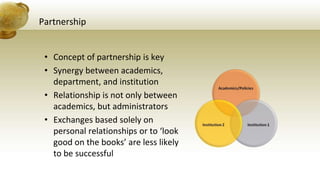

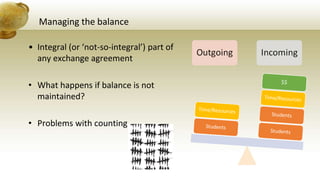

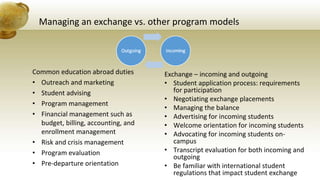

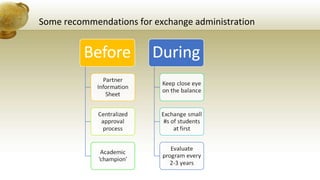

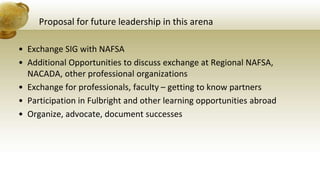

The document discusses reciprocal exchanges in international education, highlighting various models such as university-wide exchanges and third-party programs. It presents insights from surveys comparing UK and US institutions, addressing motivations for participation, cost factors, and institutional strategies. Additionally, it outlines successful exchange programs, challenges in managing partnerships, and proposes future leadership initiatives in exchange administration.