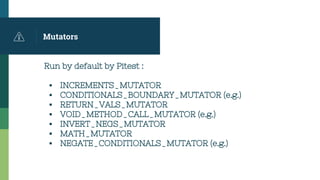

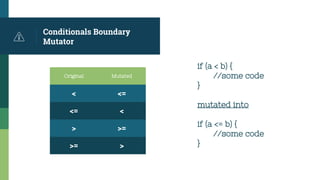

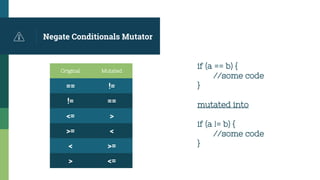

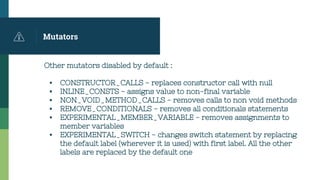

This document provides an overview of mutation testing and the Pitest tool. It defines mutation testing as seeding artificial defects into source code to check if tests detect them. It describes various mutators that Pitest uses to alter code, such as changing relational operators or removing method calls. The document also outlines how to set up Pitest in a Maven project and review the test coverage report. It concludes that mutation testing can find bugs and redundant code but requires significant time to run all mutants. Not all mutants need to be killed to ensure quality.

![Definition

Mutation testing was originally proposed by Richard Lipton as a

student in 1971 and first developed and published by DeMillo,

Lipton and Sayward. The first implementation of a mutation

testing tool has been created by Timothy Budd as part of his PhD

work (titled Mutation Analysis) in 1980 from Yale University. [6]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutationtesting-160630192753/85/Mutation-testing-4-320.jpg)

![Conclusions

Mutation testing seems powerful and research indicates that

mutation score is a better predictor of real fault detection rate

than code coverage [2]. However, it has not yet received

widespread popularity.

Creating mutations and executing tests against those mutations

is not a lightweight process and can take quite a lot of time.

In addition to finding bugs, mutation testing is a great way to

find redundant code thus making your code cleaner!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mutationtesting-160630192753/85/Mutation-testing-21-320.jpg)