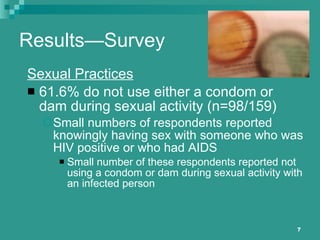

The document discusses the impact of the recession on reproductive health among women of color, emphasizing the need for multifactorial interventions in disenfranchised communities. It presents findings from various community assessments on HIV awareness and behaviors in populations, revealing significant gaps in knowledge and delayed discussions about HIV among African American youth. The conclusion underscores the critical link between social determinants and reproductive health disparities, affirming the importance of tailored public health strategies to address these issues.

![Trust of Male Partner The female students also indicated that in a relationship they have a tendency to trust their partners and may feel as though there is not a risk for HIV/AIDS and therefore a discussion about HIV/AIDS is not necessary. “ Women [are] feeling like they can trust their partners or just having their mind on some other things other than HIV risk not even thinking about it.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mtrrosaparkslecture21011-12973627444367-phpapp02/85/MTR-Rosa-Parks-Lecture-2-10-11-18-320.jpg)