The Integrated Rural Development Programme (IRDP) was the major self-employment scheme in India from 1980-1999, aiming to generate sustainable incomes for rural poor families and help them cross the poverty line. However, numerous studies found conceptual and implementation problems with IRDP, including a lack of coordination between programs, low and insufficient investment per family, and poor targeting that allowed non-poor families to participate. As a result, many IRDP beneficiaries failed to retain assets or generate enough income to escape poverty. The document discusses reforms needed to poverty alleviation programs like IRDP to make them more effective.

![ZHUH FRPPLVVLRQHG E 0LQLVWU RI 5XUDO

'HYHORSPHQW DQG WKH ILQGLQJV UHYHDO WKDW LPSOHPHQWDWLRQ ZDV IUDXJKW ZLWK VHYHUH DGPLQLVWUDWLYH SUREOHPV OLPLWLQJ DQ RYHUDOO

LPSDFW

7KH VWXG RQ %DODVRUH IRXQG WKDW SDUW SROLWLFV DQG PRQHWDU FRQVLGHUDWLRQV LQIOXHQFHG VHOHFWLRQ RI ,5'3 EHQHILFLDULHV DQG LQ

PRVW FDVHV VHOHFWLRQ JXLGHOLQHV ZHUH QRW IROORZHG 7KH VHOHFWLRQ ZDV QRW GRQH LQ WKH JUDP SDQFKDDWV ,Q -DZDKDU 5R]JDURMDQD

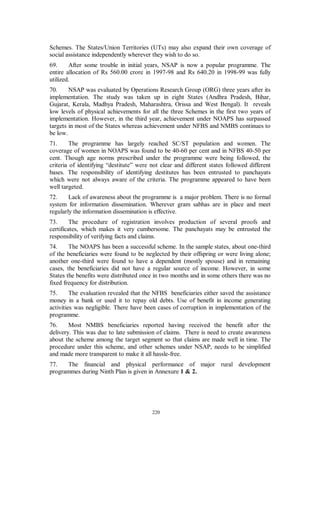

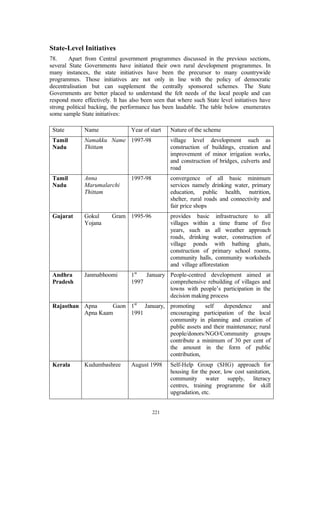

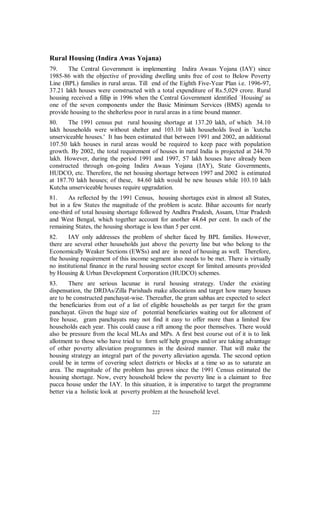

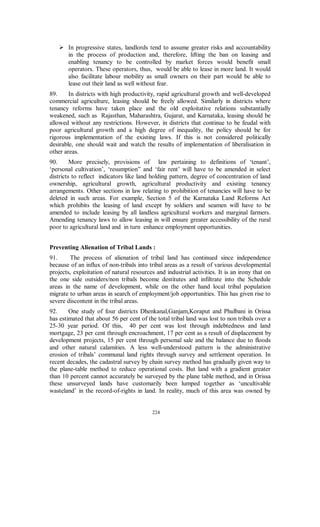

-5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mta-ch6-130210074400-phpapp01/85/Mta-ch6-10-320.jpg)