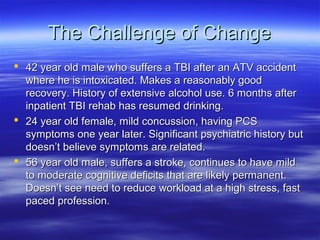

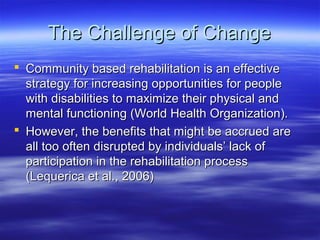

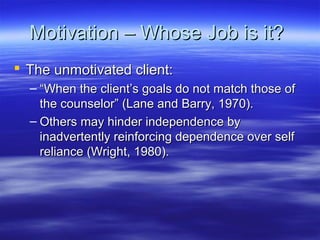

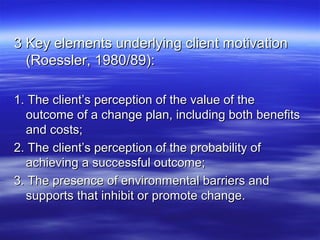

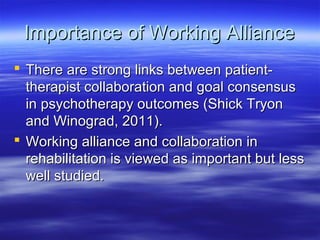

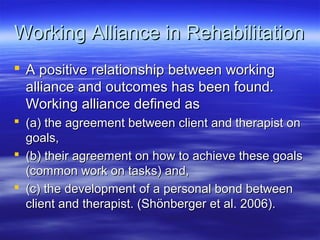

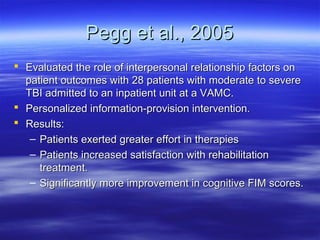

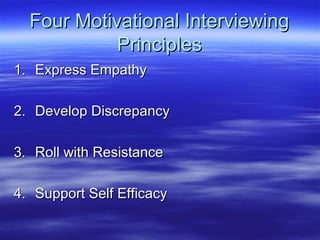

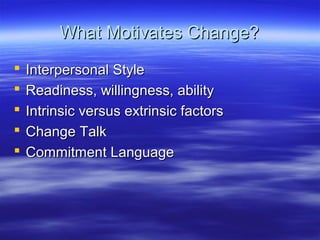

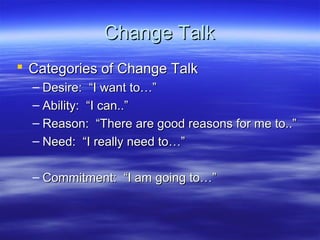

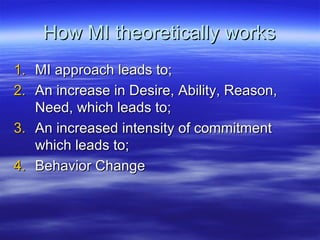

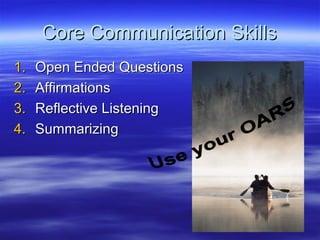

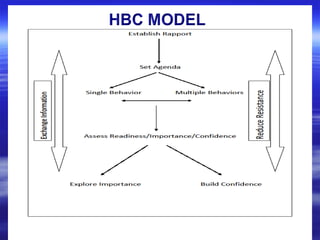

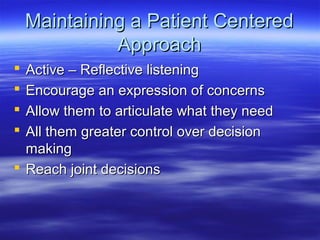

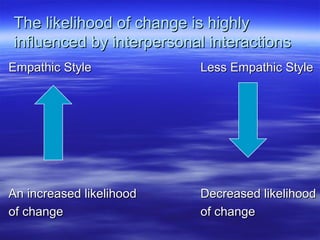

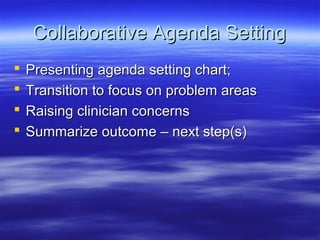

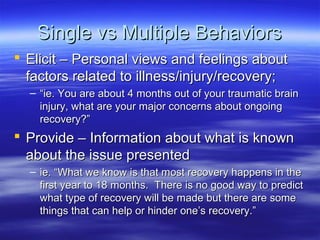

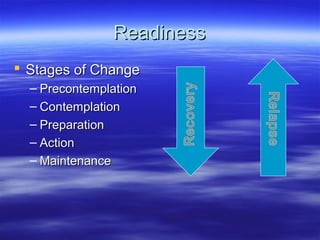

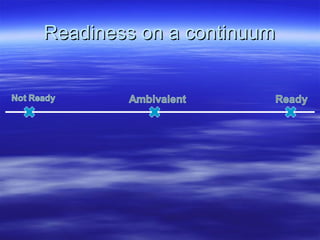

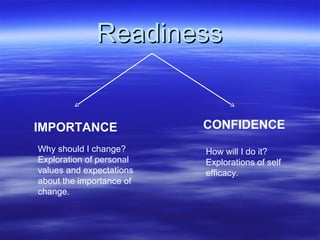

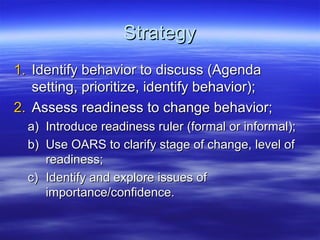

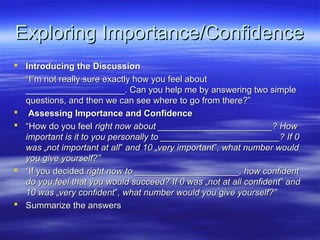

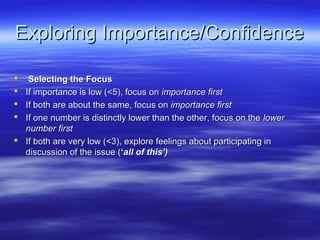

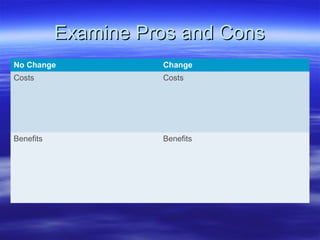

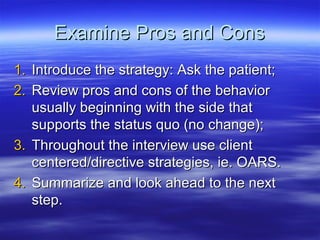

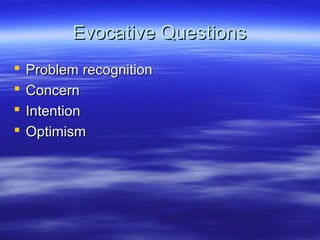

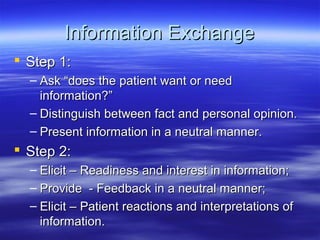

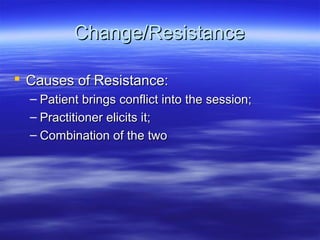

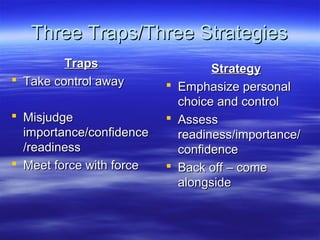

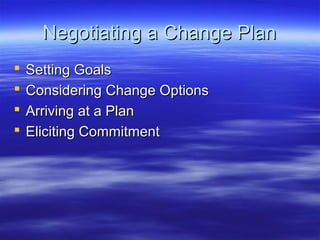

The document discusses the principles and methods of motivational interviewing in neuropsychology, emphasizing the importance of client motivation and the therapeutic alliance in rehabilitation outcomes. It highlights key factors influencing motivation and addresses the challenges faced by clients, along with techniques for effective communication and goal-setting. Additionally, it outlines motivational interviewing as a means to enhance intrinsic motivation for change through empathetic and collaborative strategies.