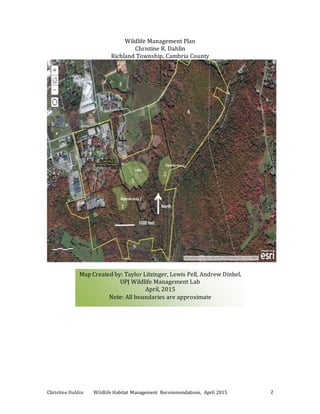

This document provides wildlife habitat management recommendations for Christine Dahlin's property in Johnstown, PA. The recommendations aim to improve riparian habitat by installing a reservoir lake fed by a levee system to regulate water flow in streams. Vegetation along the stream banks will be changed to reduce erosion and improve habitat. This will benefit species of concern including Eastern Ribbon Snake, Green Salamander, Olive-sided Flycatcher and Queen Snake. Associated species such as Chickadees, Crayfish and White-tailed Deer will also benefit from the improved habitat.

![Christine Dahlin Wildlife Habitat Management Recommendations, April 2015 10

Reference

NatureServe. 2007. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web

application]. Version 6.2. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available

http://www.natureserve.org/explorer.

Brodman Robert. Conservation Assessment. R9 Species Conservation Assessment

for the Green Salamander. Jan. 6 2004.

http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fsm91_054400.pdf

Hulse, A.C., Cj. McCroy and E. Censky 2001. Amphibians and Reptiles of

Pennsylvania and the Northeast. Cornell University Press. Ithaca

"Olive-sided Flycatcher." , Life History, All About Birds. Web. 31 Mar. 2015.

<http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Olive-sided_Flycatcher/lifehistory>.

Brandy, Paul. "Population Status." Population Status. Web. 31 Mar. 2015.

<http://www.prbo.org/calpif/htmldocs/species/conifer/osflacct.html>.

"Black-capped Chickadee." , Identification, All About Birds. Web. 31 Mar. 2015.

<http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Black-capped_Chickadee/id>.

Curry, R.L. "Black-capped Chickadee." Black- Capped Chickadee. 1 Jan. 2004. Web. 31

Mar. 2015.

<http://www98.homepage.villanova.edu/robert.curry/Documents/RLCpubs/Curry.

2012.BCCH2ndPA.pdf>.

“Crayfish.” Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. Last Updated, 2015. Accessed

3/30/15.

http://www.fish.state.pa.us/images/pages/qa/amp_rep/crayfish.htm

Dietz, Walt. “Smart Angler’s Notebook Crazy Crayfish.” Pennsylvania Angler and

Boater. September-October 2003.

http://www.fish.state.pa.us/education/catalog/crazycrayfish.pdf

“Thamnophis Sauritus Eastern Ribbon Snake” Animal Diversity Web. Last Updated

August 31, 2005. Accessed 3/30/15.

http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Thamnophis_sauritus/

Riparian Life Zones Plants and Trees. (n.d.). Retrieved April 14, 2015, from

http://shelledy.mesa.k12.co.us/staff/computerlab/ColoradoLifeZones_Riparian_Pl

ants.html#Higher_Elevation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/e8939ed1-d018-4204-9727-18245675004a-161115033616/85/mgmt-plan-10-320.jpg)