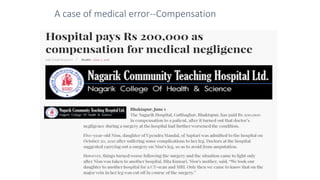

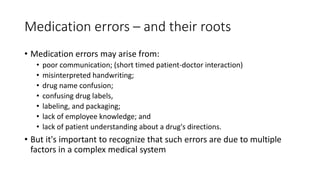

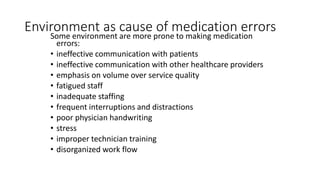

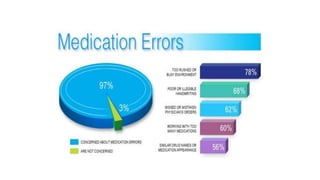

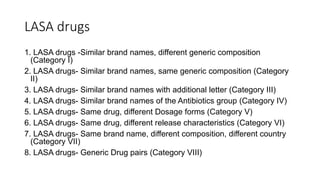

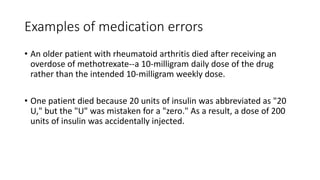

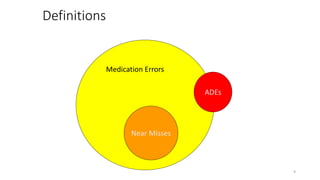

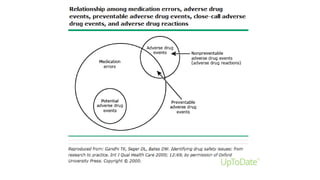

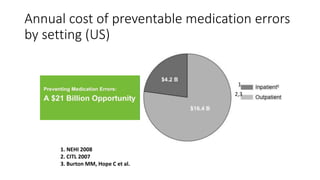

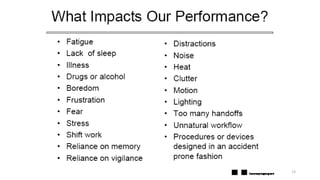

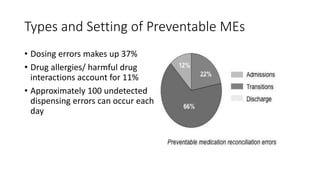

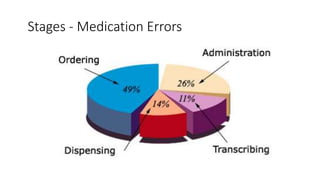

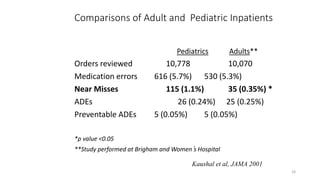

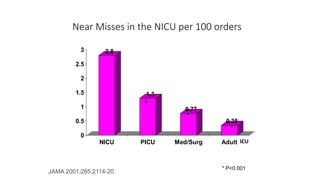

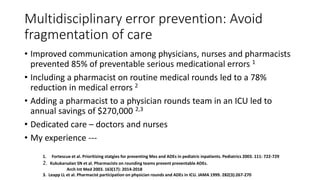

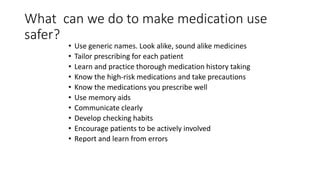

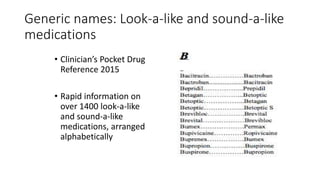

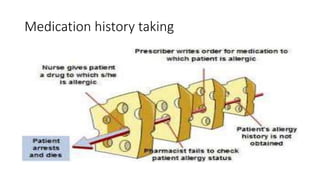

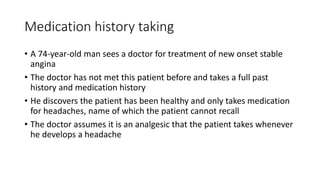

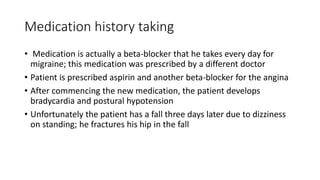

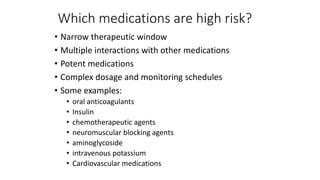

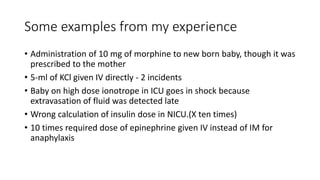

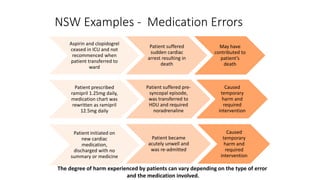

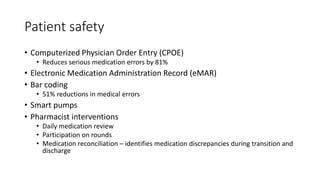

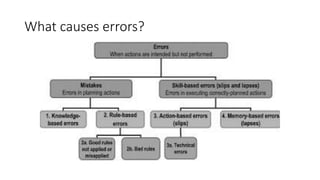

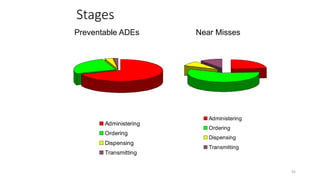

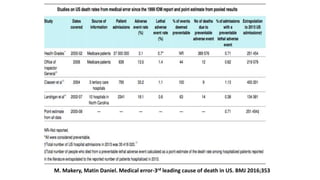

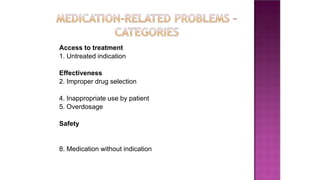

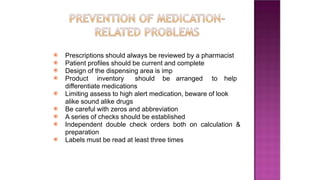

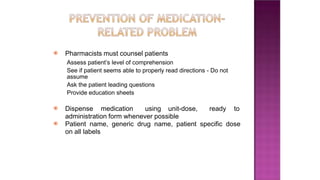

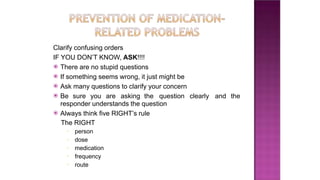

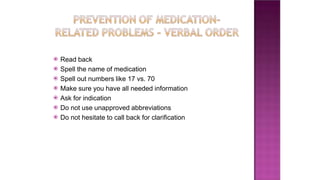

This document provides an overview of medication safety and medication errors. It defines key terms like medical error, adverse drug events, and near misses. It discusses the scale of medication errors, estimating they occur in 5-14% of doses dispensed and 1 in 100 result in an adverse drug event. Preventable medical errors occur in over 3 million hospital admissions and outpatient visits annually in the US, resulting in over 7,000 deaths each year. Factors that contribute to medication errors include complex medication regimens and lack of communication between healthcare providers. Strategies to improve safety include using generic drug names, tailoring prescriptions to each patient, thorough medication histories, awareness of high-risk medications, and encouraging patient involvement.

![⦿ Bindoff, I. K., Peterson, G. M., Tenni, P. C. and Williams, M. (2012) A clinical

knowledge measurement tool to assess the ability of communi- ty pharmacists to

detect drug-related problems. Int. J. Pharm Pract, Volume 20, Pages 238-48.

⦿ Foppe Van Mil. Drug-related problems: a cornerstone for pharmaceutical care.

Journal of the Malta College of Pharmacy. 2005; 10: 5-8.

⦿ Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am

J Hosp Pharm. 1990; 47:533–43.

⦿ Linda M. S., Peter C.M., Robert J. C. et al. Drug related problems: Their structure

and function. DCIP Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 1990;24:1093-97.

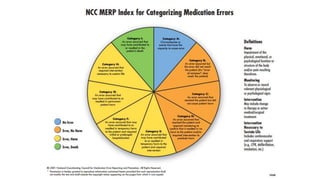

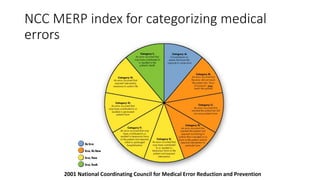

⦿ National Coordinating Council for medication error reporting and prevention (NCC

MERP). About Medication Errors. [Cited 17-04-05]. Available from http://

www.nccmerp.org/about mederrors.htm.

⦿ Ulrika, G. (2012) Effects of Clinical Pharmacists Interventions on Drug- related

Hospitalization and appropriateness of Prescribing in Elderly patients. Digitala

Vetenskapliga Arkivet, Volume 154, Page 58.

⦿ Van Mil JWF, Schulz M, Tromp TF. Pharmaceutical care, European developments in

concepts, implementation, teaching, and research; a review. Pharm. World Sci.

2004;26:303-11.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/medicatinerrorpawan-230619090633-e43026bc/85/medication-error-pptx-71-320.jpg)