This document is a thesis on actuarial analysis in social security. It acknowledges contributions from various experts who helped with the research. The thesis contains 5 chapters that discuss the role of actuaries in social security, how macroeconomic factors influence calculations, financial aspects of social security systems, an analysis of Turkey's social security system, and some actuarial calculations regarding Azerbaijan's pension system. The conclusion restates that actuaries must analyze complex interacting demographic, economic, financial and legal factors when assessing social security schemes.

![Actuarial analysis in social security

The experience analysis and the economic and demographic prospects indicate areas of

adjustment to the actuarial assumptions. For example, a recent change in retirement behaviour may

induce a new future expected retirement pattern. A slowdown in the economy will require a

database of the number of workers contributing to the scheme. However, as actuarial projections for

pensions are performed over a long period, a change in recently observed data will not necessarily

require any modifications to be made to long-term assumptions. The actuary looks primarily a

consistency between assumptions, and should not give undue weight to recent short-term

conjectural effects.

There are 2 actuarial techniques for the analysis of a pension scheme: the projection technique

and the present value technique

1.2.1 – The projection technique

There are different methodologies for social security pension scheme projections. These include:

(a) actuarial methods,

(b) econometric methods and

(c) mixed methods.

Methods classified under (a) have long been applied in the field of insurance and have also proved

valuable for social security projections.

Methods classified under (b) are in effect extrapolations of past trends, using regression

techniques. Essentially the difference between the two is that actuarial methods depend on

endogenous (internal) factors, whereas econometric methods are based on exogenous factors.

Methods classified under (c) rely partly on endogenous and partly on exogenous factors.

The first step in the projection technique is the demographic projections, production of estimates

of numbers of individuals in each of the principal population subgroups(active insured persons,

retirees, invalids, widows/widowers, orphans )at discrete time-points (t=1,2,..),starting from given

initial values (at t=0).

The demographic projection procedure can be regarded as the iteration of a matrix multiplication

operation, typified as follows: 2

nt = nt −1 ⋅ Qt −1 (1.1)

in which nt is a row vector whose elements represent the demographic projection values at time t

and Qt −1 is a square matrix of transition probabilities for the interval (t-1, t) which take the form:

nt = [A(t) R(t) I(t) W(t) O(t)]

(1.2)

p q q q (aa)

q

(ar) (ai) (aw) (ao)

(rr)

0 p 0 q (rw) q (ro)

(1.3)

Qt = 0 0 p (ii) q (iw) q (io)

0 0 0 p (ww) 0

0 0 0 0

p (oo)

The elements of the matrix and the symbols have the following significance:

p (rr) denotes the probability of remaining in the same r;

q (rs) denotes the probability of transition from status r to status s;

a, r , i , w and o respectively represent active lives , retirees, invalids, widows/widowers and

orphans .

2

See for instance, Subramaniam Iyer (1999)”Actuarial mathematics of social security pensions” ,International Labour Office

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbathesis-100820001545-phpapp01/85/MBA-thesis-7-320.jpg)

![Actuarial analysis in social security

The above procedure, however, is not applied, at the level of total numbers in the subpopulations.

In order to improve precision, each subpopulation is subdivided at least by sex and age. Preferably,

the active population would be further subdivided by past service. The procedure is applied at the

lowest level of subdivision and the results aggregated to give various subtotals and totals. The

matrix Q will be sex-age specific, it can also be varied over time if required. As regards survivors,

an additional procedure is required after each iteration to classify new widows/widowers and

orphans arising from the deaths of males/females aged x according to the age of the

widow/widower or of the orphan before proceeding to the next iteration.

For carrying out the demographic projections it is necessary to adopt an actuarial basis,

consisting of the elements listed below. They should be understood to be sex specific. For brevity,

time is not indicated as a variable, but some or the entire basis may be varied over time.

a - The active table l xa , b ≤ x ≤ r , where b is the youngest entry age and the r the highest

retirement age. This is a double decrement table allowing for the decrements of death and invalidity

only. The associated dependent rates of decrement are denoted by q x (mortality) and i x (invalidity).

a

Retirement is assumed to take place at exact integral ages, just before each birthday, r x denoting the

proportion retiring at age x.

i

b - The life table for invalids l x , b ≤ x < D and the associated independent mortality rate q xi.

c - The life table for retired persons, l xp , r ≤ x < D (where r is the lowest retirement age and D is

p

the death age) and the associated independent rate of mortality q x

d - The double decrement table for widows/widowers, l y , y* ≤ y ≤ D (where y *is the lowest age

w

w

of a widow /widower) and the associated dependent rates of decrement q y (mortality) and

(remarriage) h y

o * *

e - The single decrement table for orphans, l z , 0 ≤ z ≤ z where z is the age limit for orphans’

pensions and the associated independent mortality rate q o z

f - w,x the proportion of married persons among those dying at age x.

g - y x , the average age of the spouse of a person dying at age x.

h - n x , the average number of orphans of a person dying at age x.

i - z x , the average age of the above orphans.

The following expressions for the age and sex – specific one year transition probabilities are

based on the rules of addition and multiplication of probabilities:

Active to active p (aa) = (1 - q a - i x ) ⋅ (1 - rx + 1 )

x x (1.4)

Active to retiree q (ar) = (1 - q a - i x ) ⋅ rx +1

x x

(1.5)

Active to invalid q (ai) = (1 - 0,5 ⋅ q ix ) ⋅ i x

x (1.6)

(1.7)

Active to widow/widower q (aw)x = q (aw1)

x + q (aw2)

x

(1.7.a)

x x [

q (aw1) = q a w x +0,5 1 - 0,5(qwx + hyx )

y ]

1 i

q (aw2) = ix

x

2

[

q x w x +0,75 1 - 0,25(qwx + hyx )

y ] (1.7b

)

Retiree to retiree p (rr) = 1 - q p

x x (1.8)

Retiree to widow/widower x x [

q (rw) = q p w x +0,5 1 - 0,5(qwx + hyx )

y ] (1.9)

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbathesis-100820001545-phpapp01/85/MBA-thesis-8-320.jpg)

![Actuarial analysis in social security

Invalid to invalid p (rr) = 1 - q ix

x (1.10)

Invalid to widow/widower

[

q (iw) = q ix w x +0,5 1 - 0,5(qwx + hyx )

x y ] (1.11)

Widow/widower to widow/widower

p (ww) = 1 - q w - h x

x x (1.12)

Each iteration is assumed to operate immediately after the retirements (occurring at the end of

each year of age).Under the assumption of uniform distribution of decrements over each year of

age, the decrements affecting active persons, retirees and existing invalids –in (1.6),( 1.7a), (1.9)

and (1.11) are assumed to occur, on average at the of six months, new invalids dying before the end

of the year are assumed to die at the end of nine months in (1.7b).

It will be noted that equation (1.7) has two components: (1.7a) relating to deaths of active insured

persons in the age range (x, x+1) and (1.7b) relating to active persons becoming invalid and then

dying at by age x+1. It is understood that the values of w x corresponding to fractional ages which

occur in the above formula would be obtained by interpolation between the values at adjacent

integral ages. Expressions for transition probabilities concerning orphans, corresponding to (1.7a),

(1.7b), (1.9), (1.11) and (1.12) can be derived on the same lines as for widows/widowers.

Starting from the population data on the date of the valuation (t=0), the transition probabilities

are applied to successive projections by sex and age (and preferably by past service , in the new

entrants of the immediately preceding year have to be incorporated before proceeding to the next

iteration. The projection formula for the active insured populations are given below, the method of

projecting the beneficiary populations is illustrated with reference retirement pensioners.

Notation

• Act(x ,s ,t ) denotes the active population aged x nearest birthday , with curtate past service

duration s years at time t, b ≤ x < r, s ≥ 0

• Ac (x , t) denotes the active population aged x nearest birthday at time t. The corresponding

beneficiary populations are denoted by Re(x, t), In (x, t) and Wi (x, t).

• A(t) denotes the total active population at time t. The corresponding beneficiary populations

are denoted by R( t), I (t) and W ( t).

• The number of new entrants aged x next birthday in the projection year t, that is in the

interval (t-1,t ) is denoted by N(x,t)

The projection of the total active and beneficiary populations from time t-1 to time t is

expressed by the equation

r

A(t ) = ∑∑ Act ( x, s, t ) + Act ( x-1,s-1,t-1) ⋅ ( p (aa) − q xar ) − q xai ) − q xaw) − q x )

x-1

( ( ( a

(1.13)

x =b s > 0

D

R (t ) = ∑ Ac(x − 1,t − 1) ⋅ q (ar) + Re(x − 1,t − 1) ⋅ (p (rr) − q x )

x −1 x −1

r

(1.14)

x =r

After the demographic projections is the production of estimates of the total annual insured salary

bill and of the total annual amounts of the different categories of pensions “in force” at discrete

time points (t=1, 2…) starting from given initial values at t=0. These aggregates are obtained by

applying the appropriate per capita average amounts (of salaries or of pensions, as the case may be)

to each individual element of the demographic projections and the summing. The average amounts

are computed year by year in parallel with the progress of the corresponding demographic

projection. An average per capita amount (salary or pension, as the case may be) is computed for

each distinct population element generated by the demographic projection; if different elements are

aggregated in the demographic projection –for example, existing invalids surviving from age x to

x+1 and new invalids reaching age x+1 at the same time –a weighted per capita average amount is

computed to correspond to the aggregated population element.

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbathesis-100820001545-phpapp01/85/MBA-thesis-9-320.jpg)

![Actuarial analysis in social security

4. Actuarial practice in Social Security System of Turkey

During the last decade, the publicly managed pay-as-you-go (PAYG) pension (old-age insurance)

system in Turkey began to face serious financial difficulties due to generosity of pension benefits

relative to contributions, combined with unrealistically low statutory entitlement ages. When the

deficits generated by the system exceeded tolerable limits, a major pension reform bill was

prepared to set key program parameters straight.

Taking 1995 as the base year, and the prevailing conditions in that year as given, several scenario

analyses are carried out. A pension model that is based on the contribution and pension

characteristics of Turkey, such as the minimum retirement age, minimum contribution period,

replacement ratio, contribution rate, etc., and Turkish demographic and labor market data are used

in system simulation. Scenario analysis indicates that even with scenarios, with no shocks

introduced to the system, it is financially possible for the system to be viable.

4.1 Characteristics of Turkish Social Security System (TSSS)

Old-age insurance operations of the publicly managed social security system in Turkey were set

up in the 1940s to offer universal coverage to workers employed by public and private sectors alike.

The system is made up of three different and distinct branches, each providing pension benefits in

return for compulsory participation in retirement plans run on a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) basis. Prior

to 2003, additional coverage on a voluntary basis was only available through a number of private

pension funds set up by some companies, banks etc. to provide optional coverage to their own

employees. Following the completion of legal and regulatory framework to allow working

individuals to voluntarily purchase optional retirement plans from private companies in 2002, most

insurance companies began to sell optional coverage through money purchase schemes in 2003.

The initial TSSS law allows providing five types of insurance:

I- Insurance against natural disability old age and death.

II- Insurance against work injuries and occupational diseases.

III- Insurance against temporary disability due to sickness or motherhood.

IV- Health insurance for the worker and his/her dependent.

V- Unemployment.

Although the TSSS provides only the first two types of insurance coverage, the attention toward

this corporation has increased substantially from the time it was established especially if the

substitute provisions are absent and the private insurance system in Turkey is still immature and

needs imminent reform.

According to State Planning Organization of Republic of Turkey, 48-50 percent of the workers in

Turkey have social security coverage. There are three major publicly administered social security

institutions, with a combined pool of over 14.3 million active participants in 2006. These are the

Social Insurance Institution [Sosyal Sigortalar Kurumu (SSK)], which is open to private sector

employees and workers in the public sector, Retirement Fund [Emekli Sandigi(ES)], which covers

civil servants, and Bag-Kur (BK), which is a fund for the self-employed. Approximately 59 percent

of the insured population is covered by SSK, 17 percent by ES, and 24 percent by BK. The share of

privately insured individuals is a trivial 0.5 percent in the population.

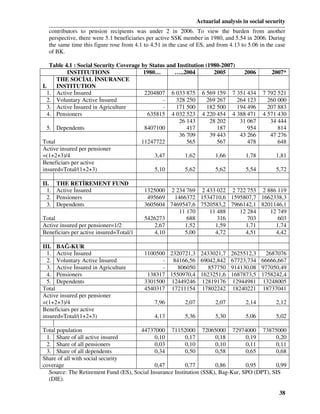

The data in Table 1 provide additional information on the three main components, and trace out

the evolution of the system. In 1980 there were close to 1.3 million pensioners, implying

approximately one pension recipient for 3.65 contributors to the pay-as-you-go system. In 2006 the

number of pensioners exceeded 7.7 million, and the number of contributors per pensioner was

down to 2. The situation is especially acute in the case of SSK and ES, where the ratio of

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mbathesis-100820001545-phpapp01/85/MBA-thesis-37-320.jpg)