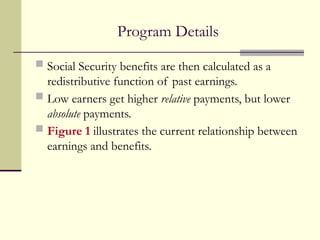

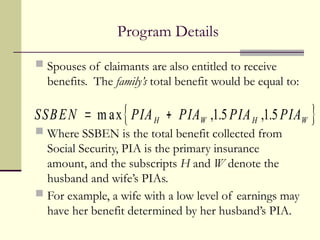

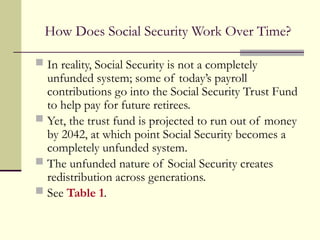

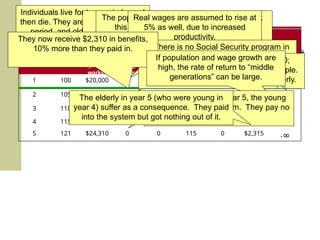

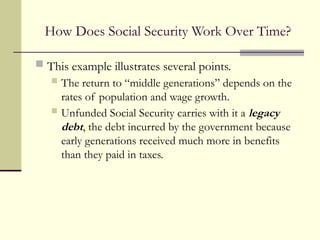

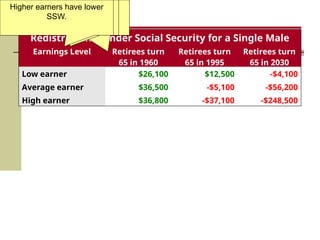

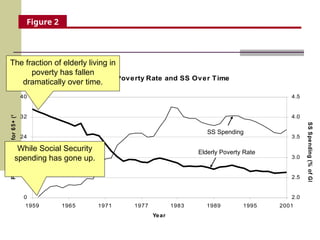

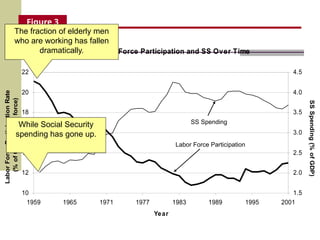

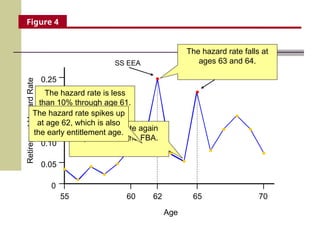

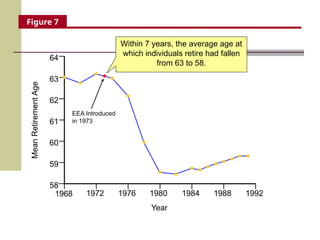

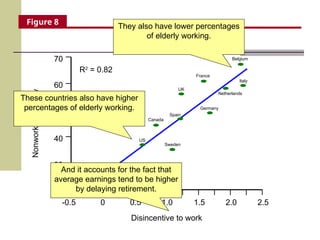

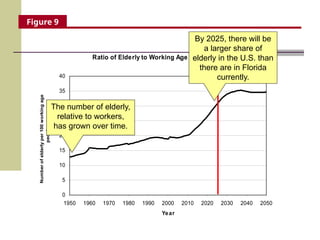

Social Security is a federal program that provides income support for the elderly, funded by payroll taxes from workers, with a projected $3.7 trillion shortfall over 75 years. The program's structure redistributes benefits based on past earnings, favoring low earners, while its sustainability is challenged due to demographic and economic factors, potentially leading to insolvency by 2042. Despite concerns, Social Security helps reduce elderly poverty and smooth consumption during retirement, though it encourages early retirement through implicit and income effects.