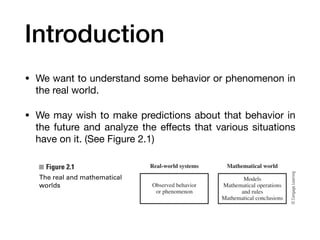

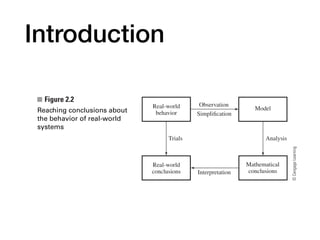

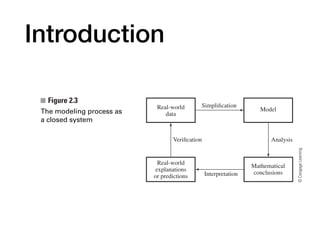

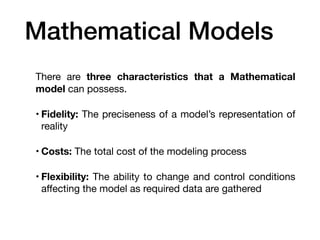

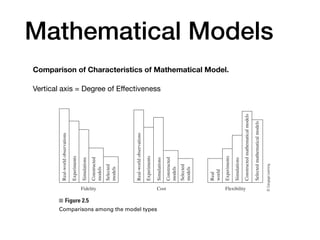

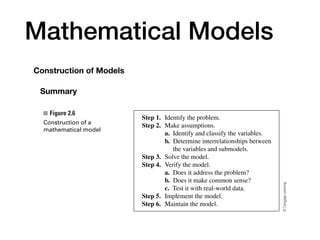

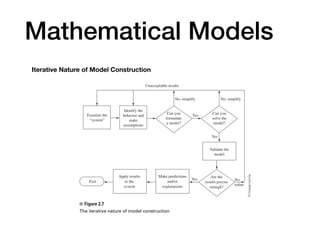

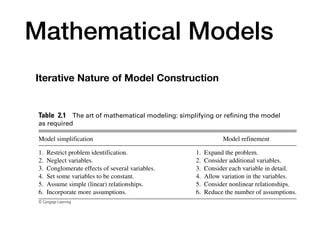

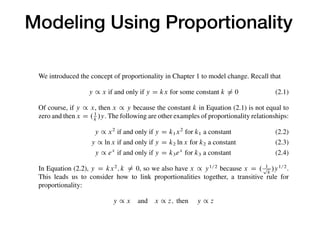

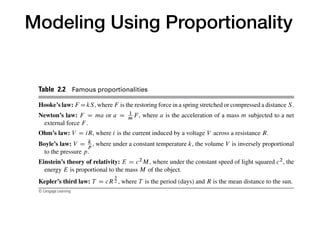

Chapter 2 discusses the mathematical modeling process, focusing on understanding real-world phenomena through mathematical models and their construction. It outlines steps to create models, including identifying problems, making assumptions, solving and verifying models, and implementing them for practical use. Key concepts such as fidelity, cost, and flexibility of models, as well as the iterative nature of refining them, are emphasized throughout the chapter.