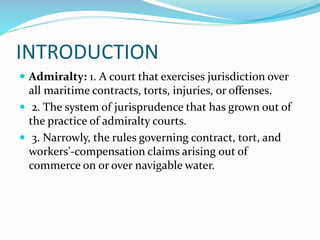

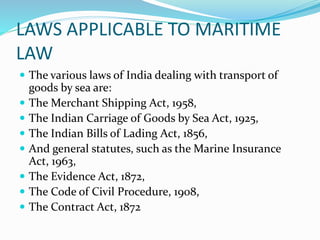

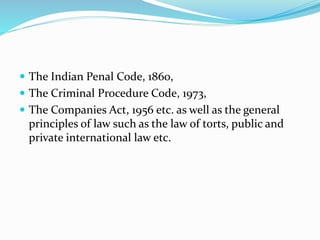

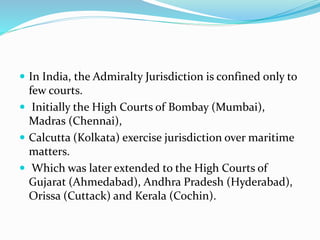

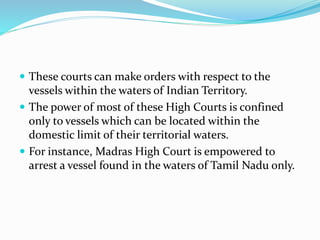

This document provides an introduction and overview of maritime law and the admiralty jurisdiction in India. It discusses key concepts like admiralty, maritime law, and the law of the sea. It traces the historical development of merchant shipping law in India from British rule. The basis of current Indian law is international conventions and UK law. The document outlines the laws applicable to maritime matters in India and the courts that exercise admiralty jurisdiction. It also describes the process and documents required for arresting a ship in India.