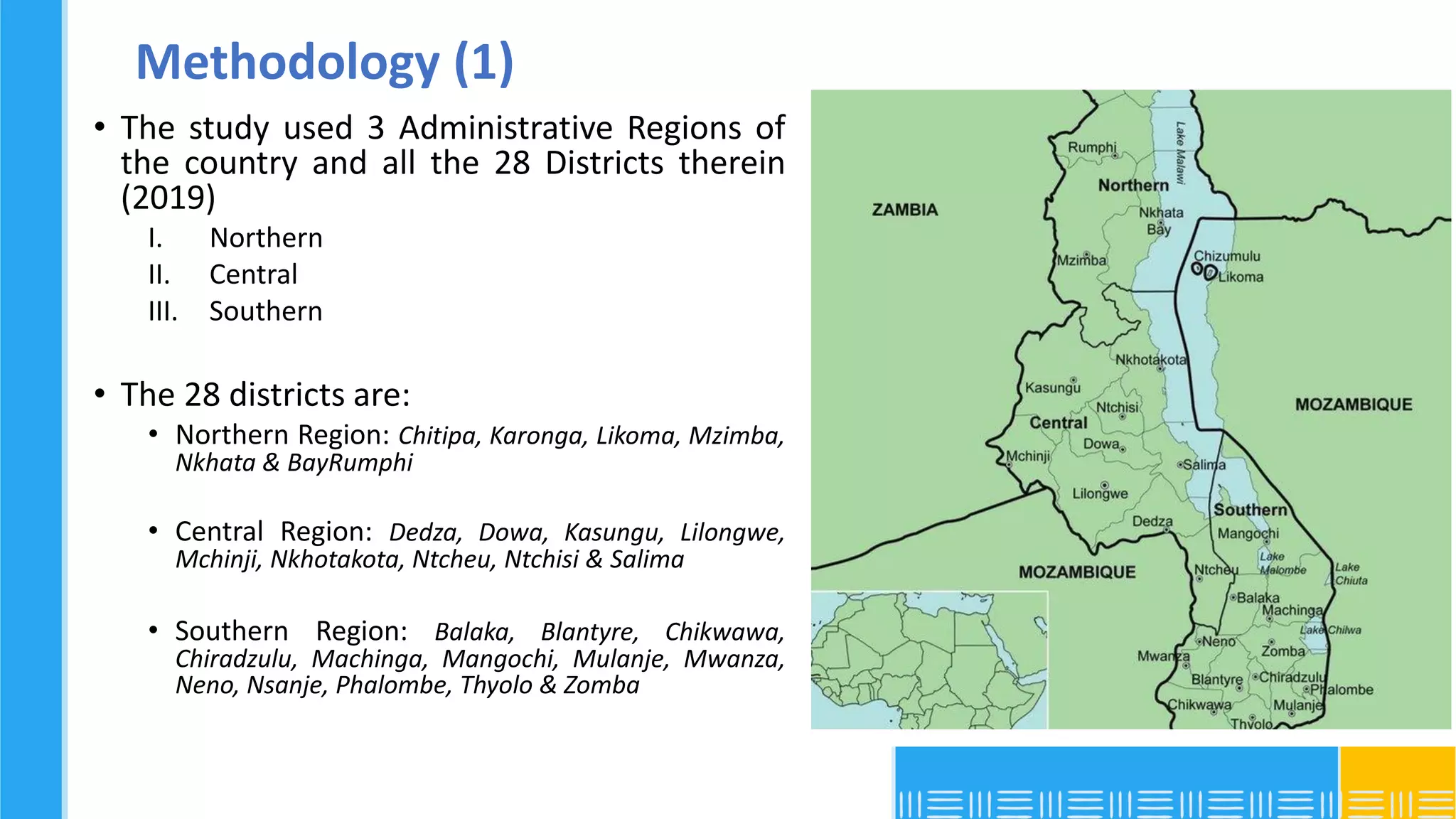

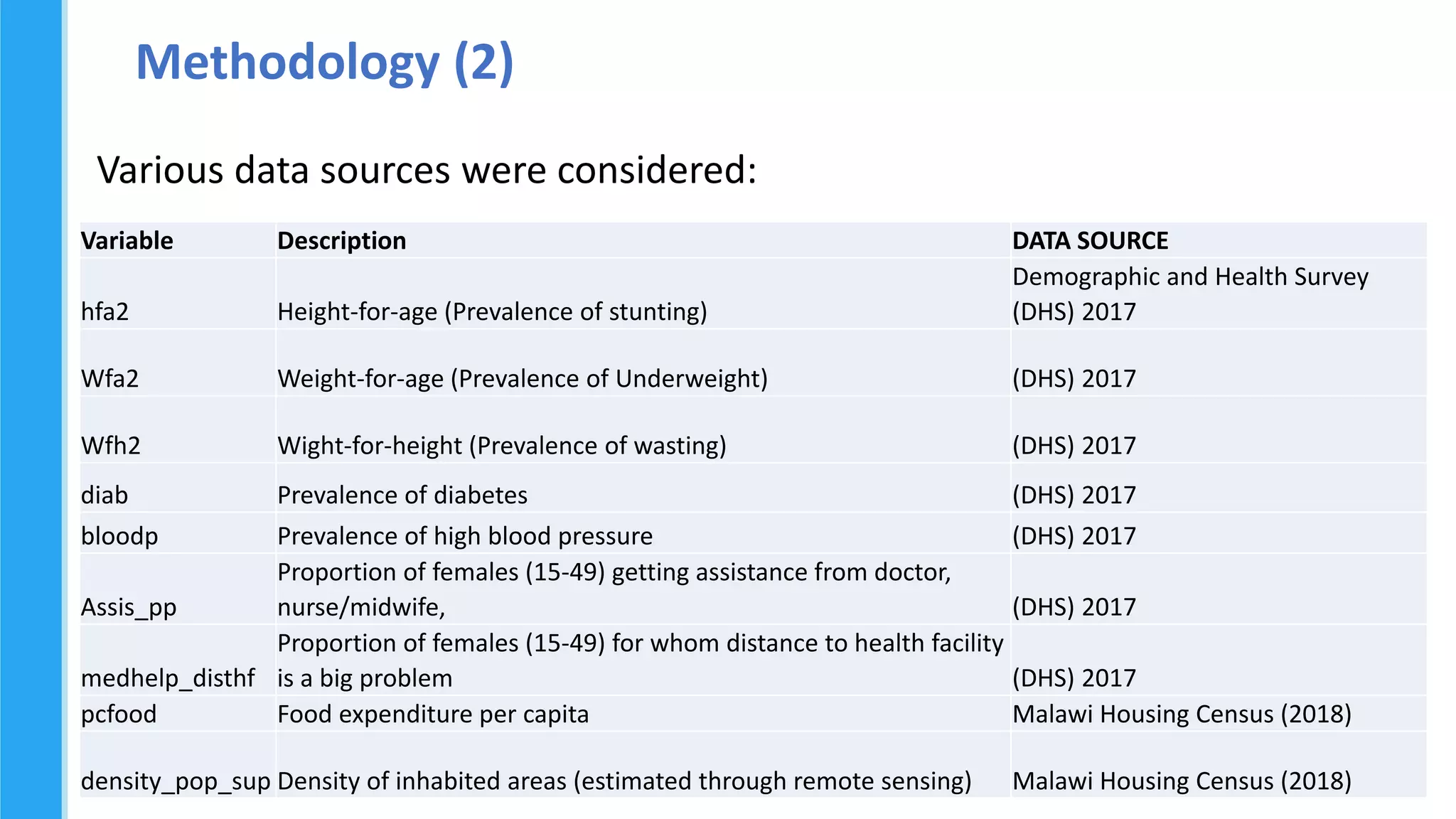

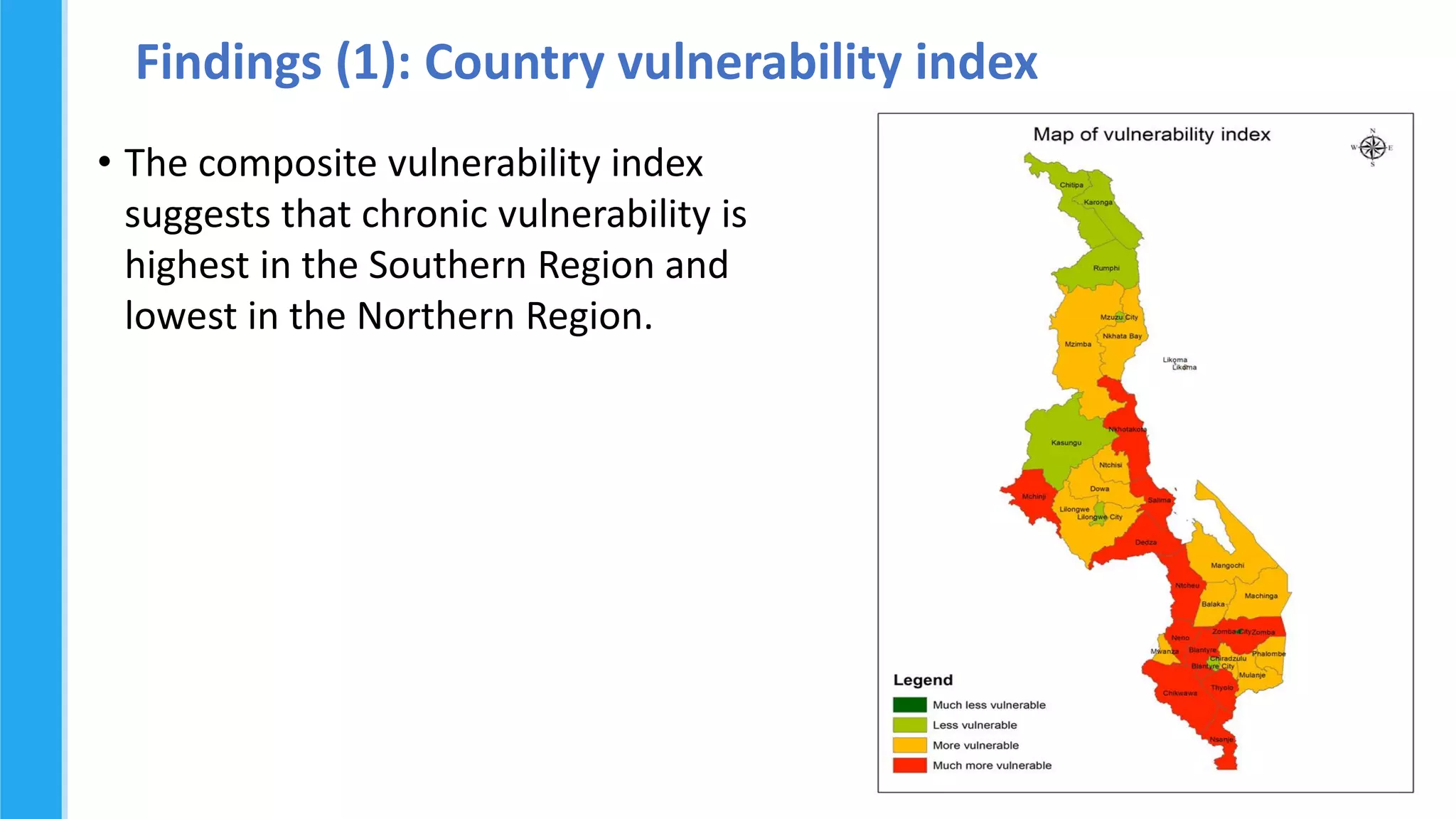

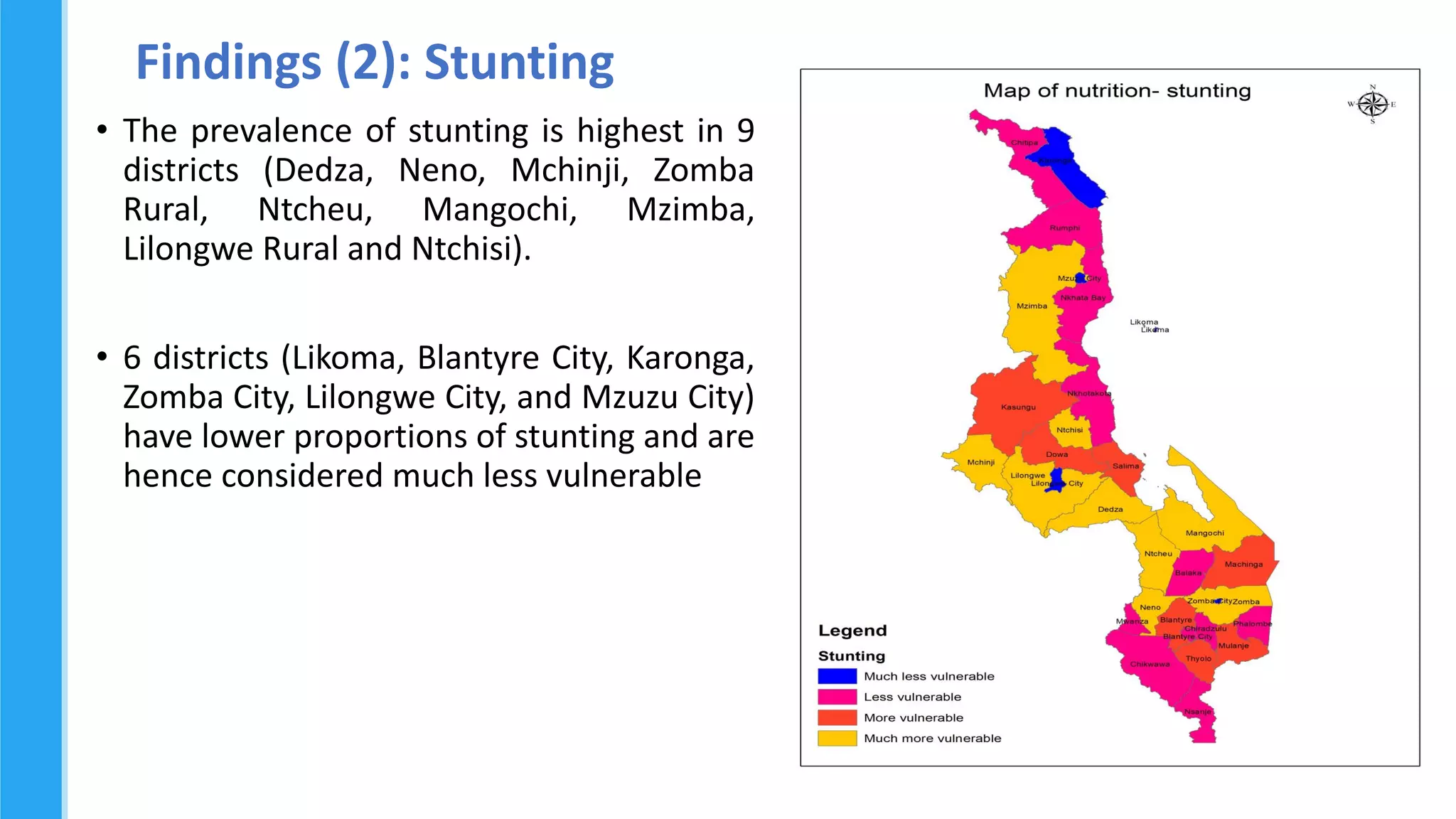

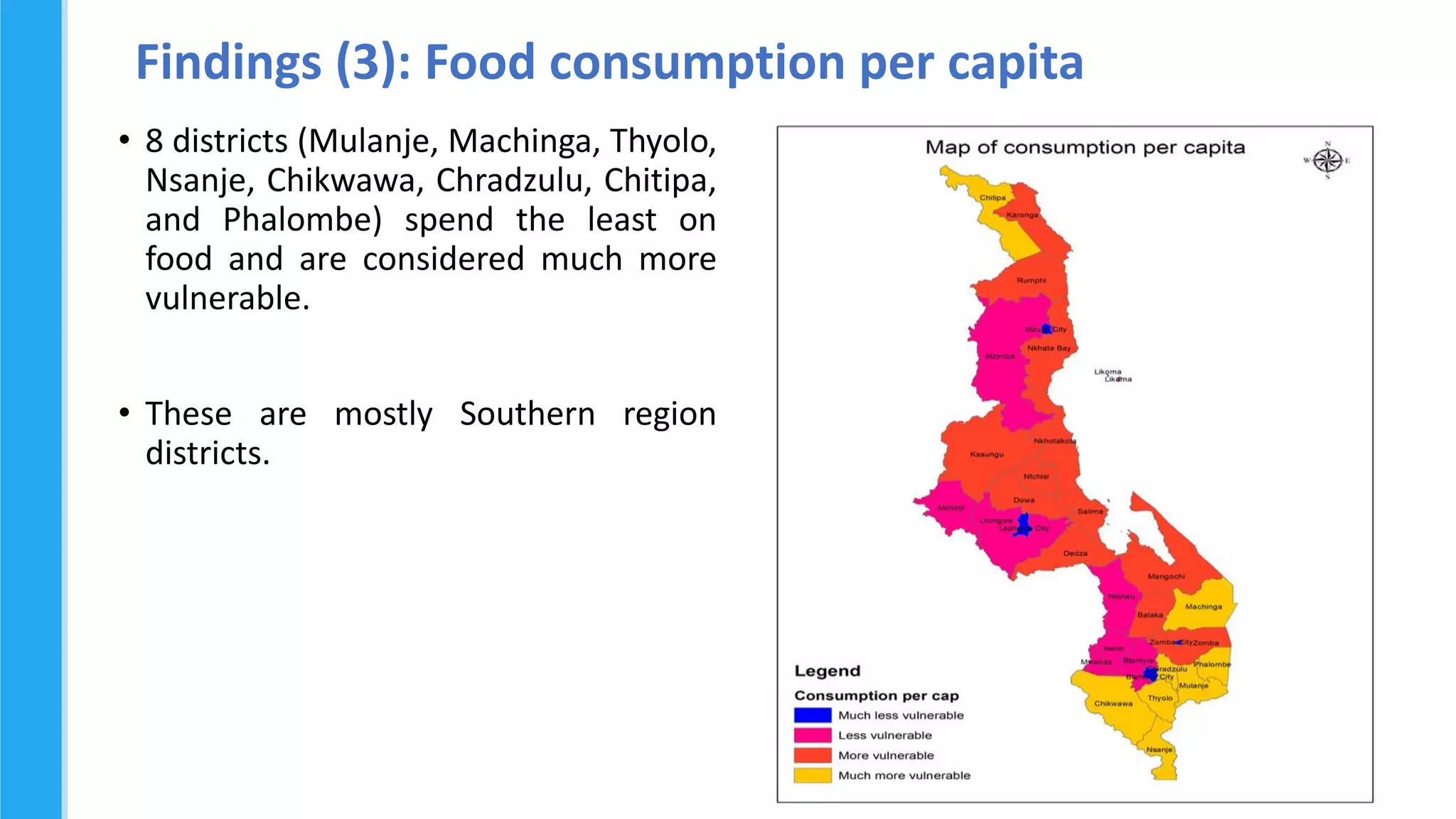

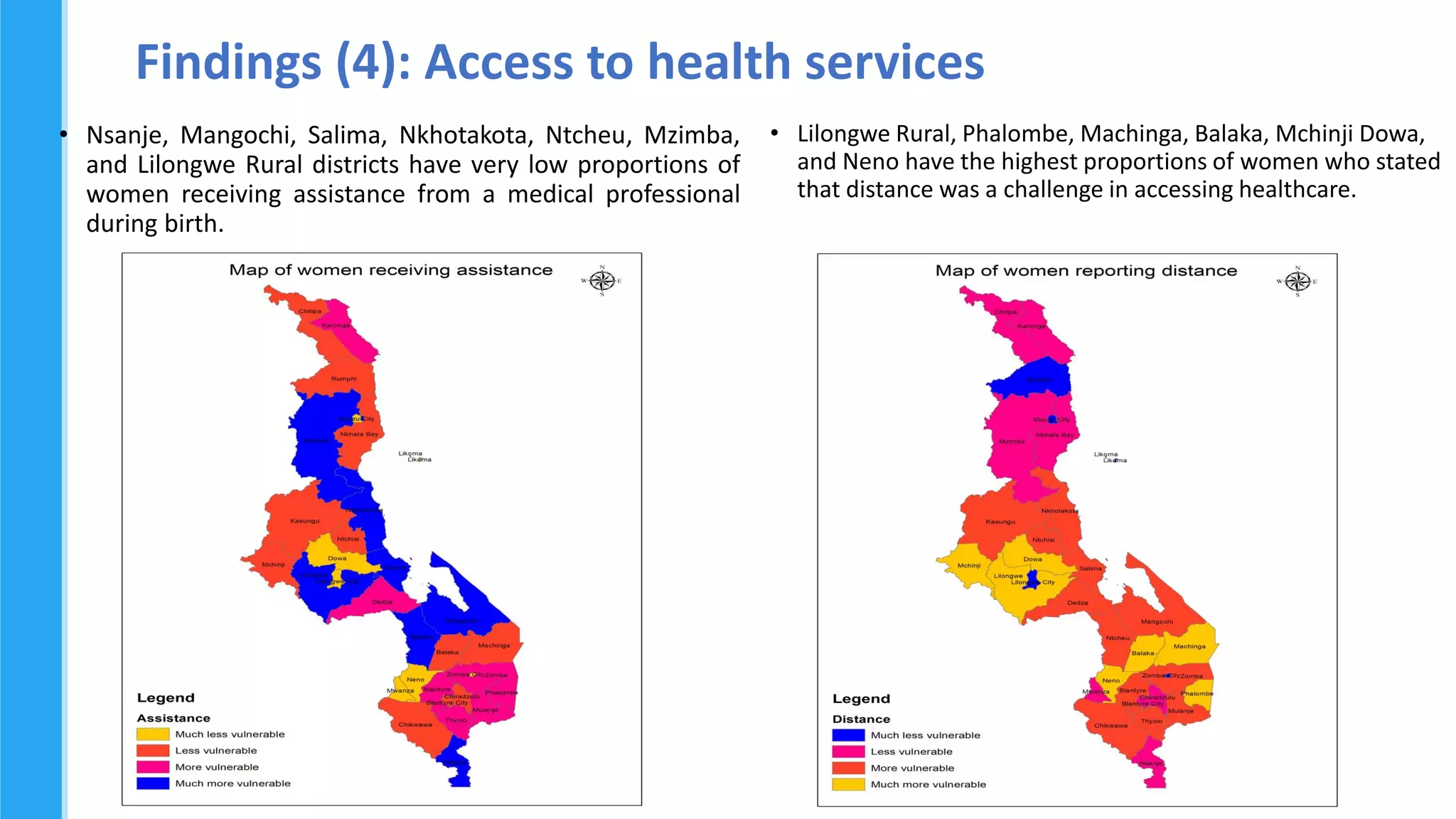

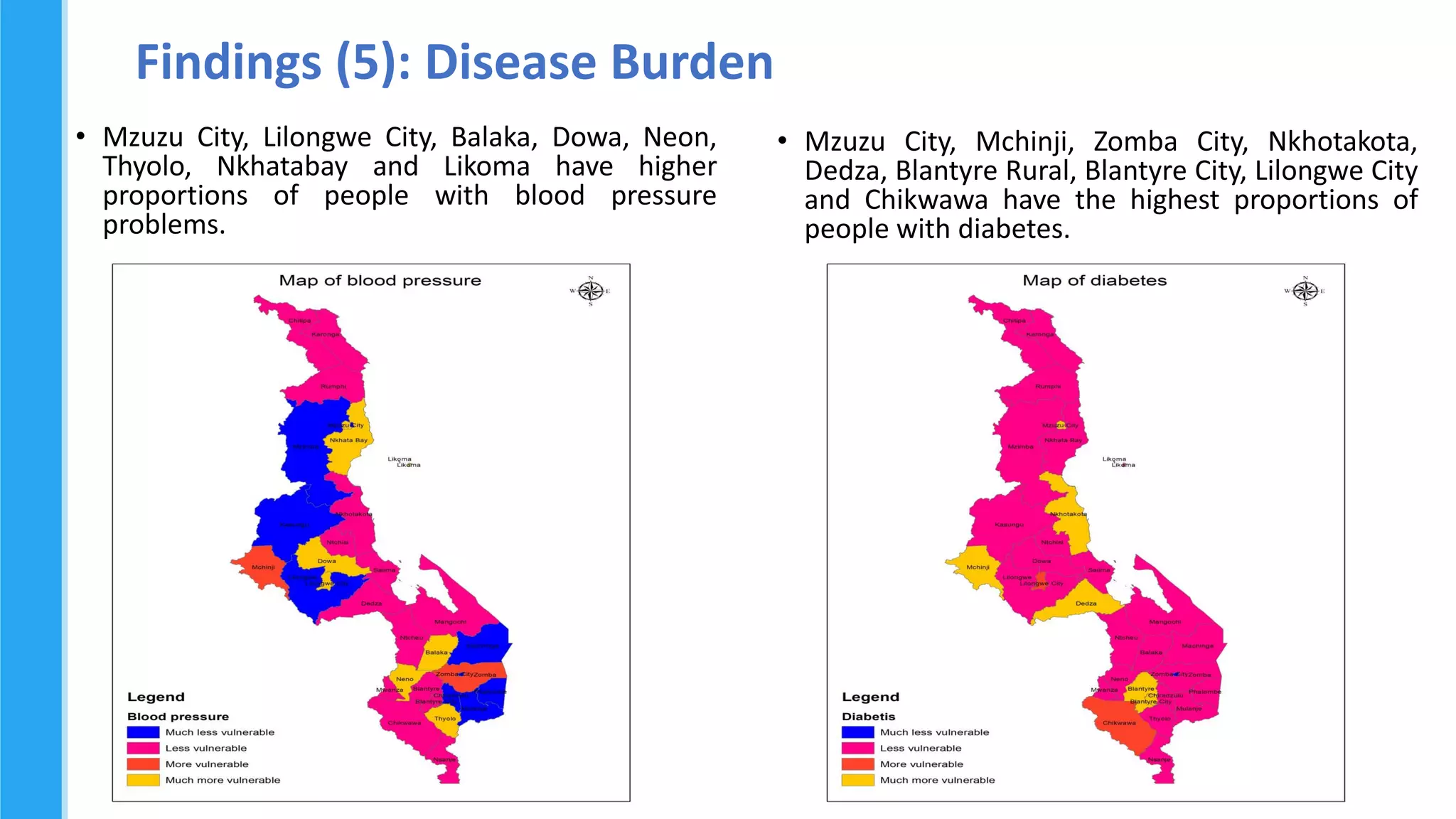

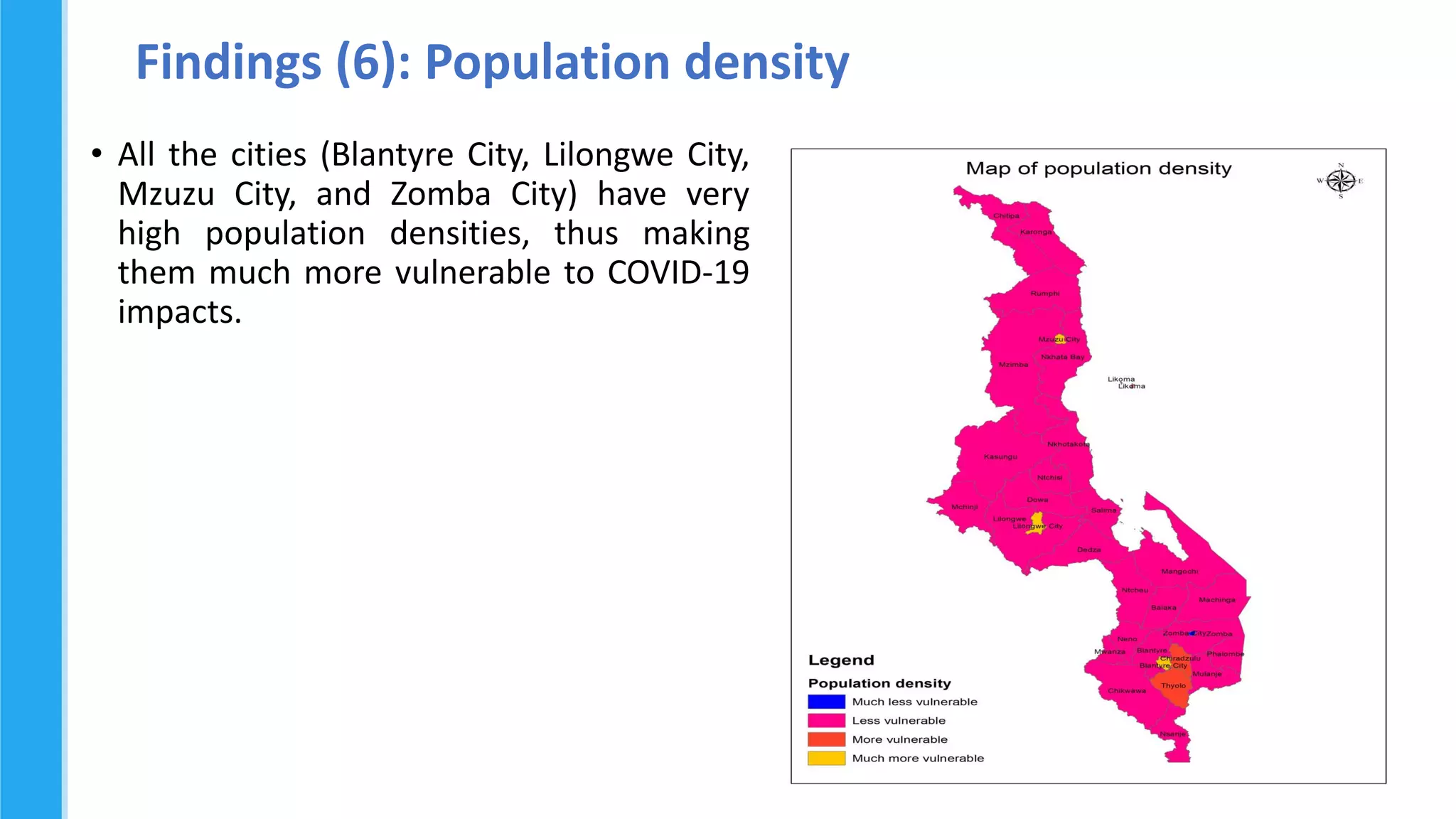

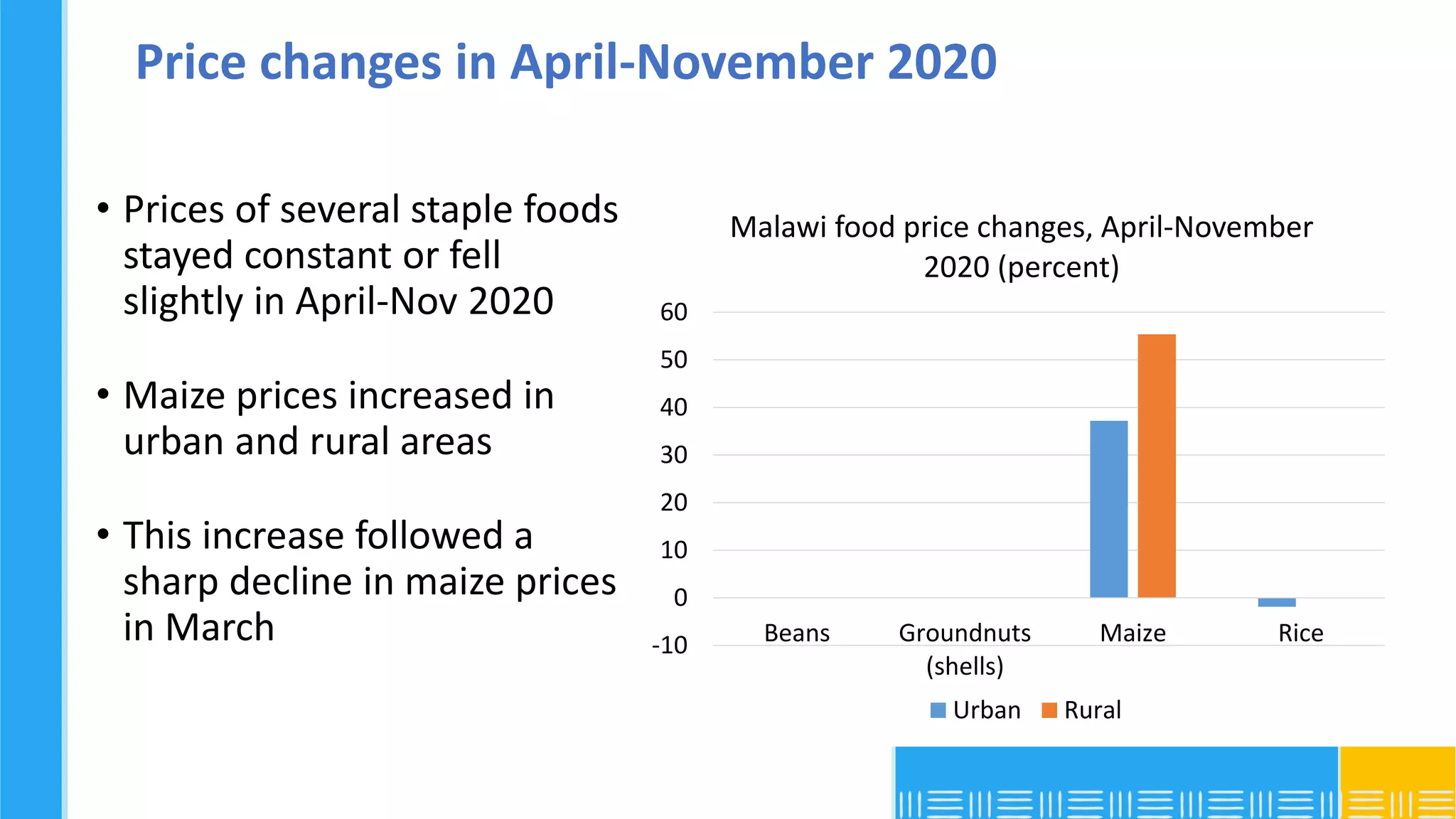

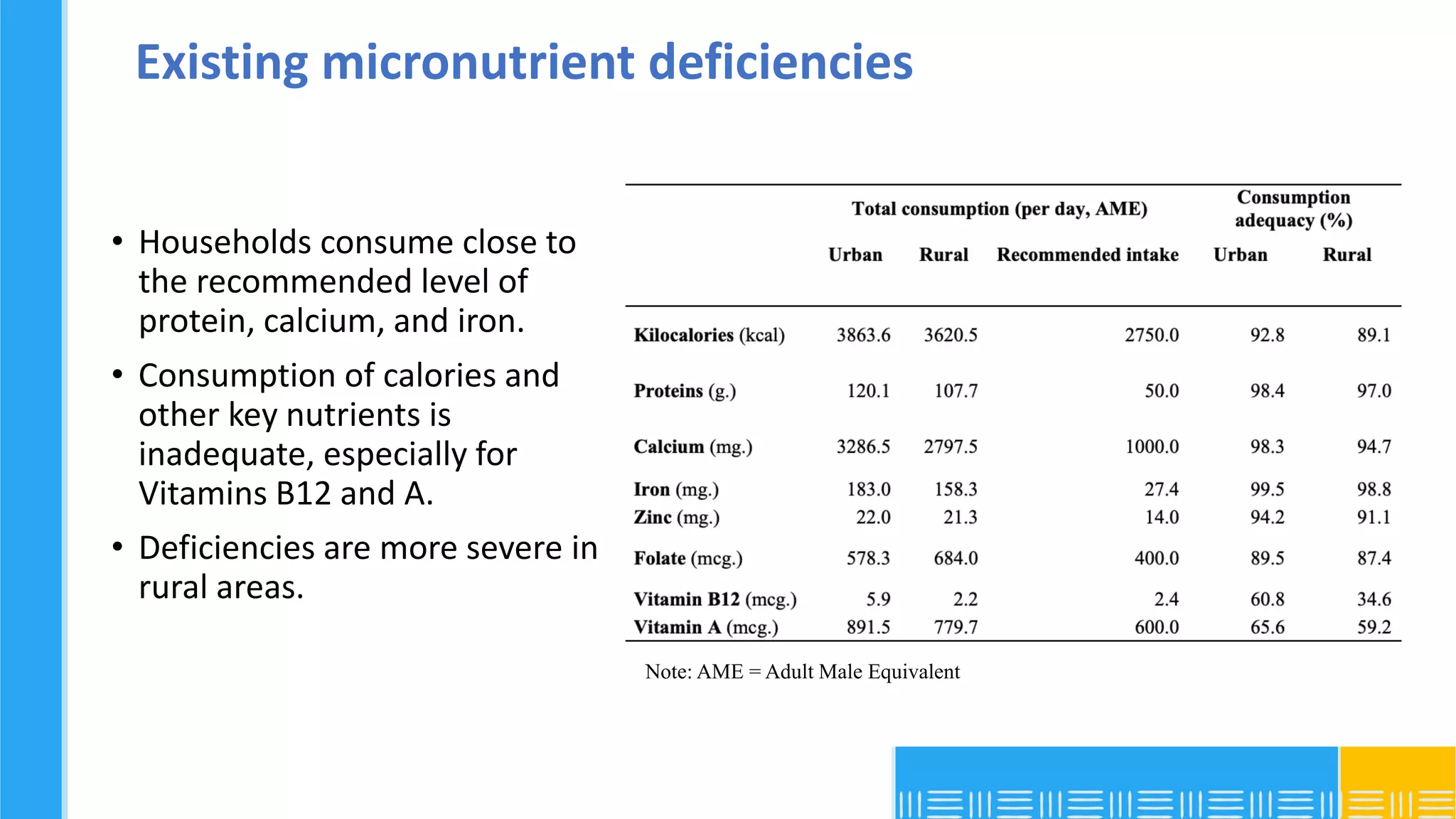

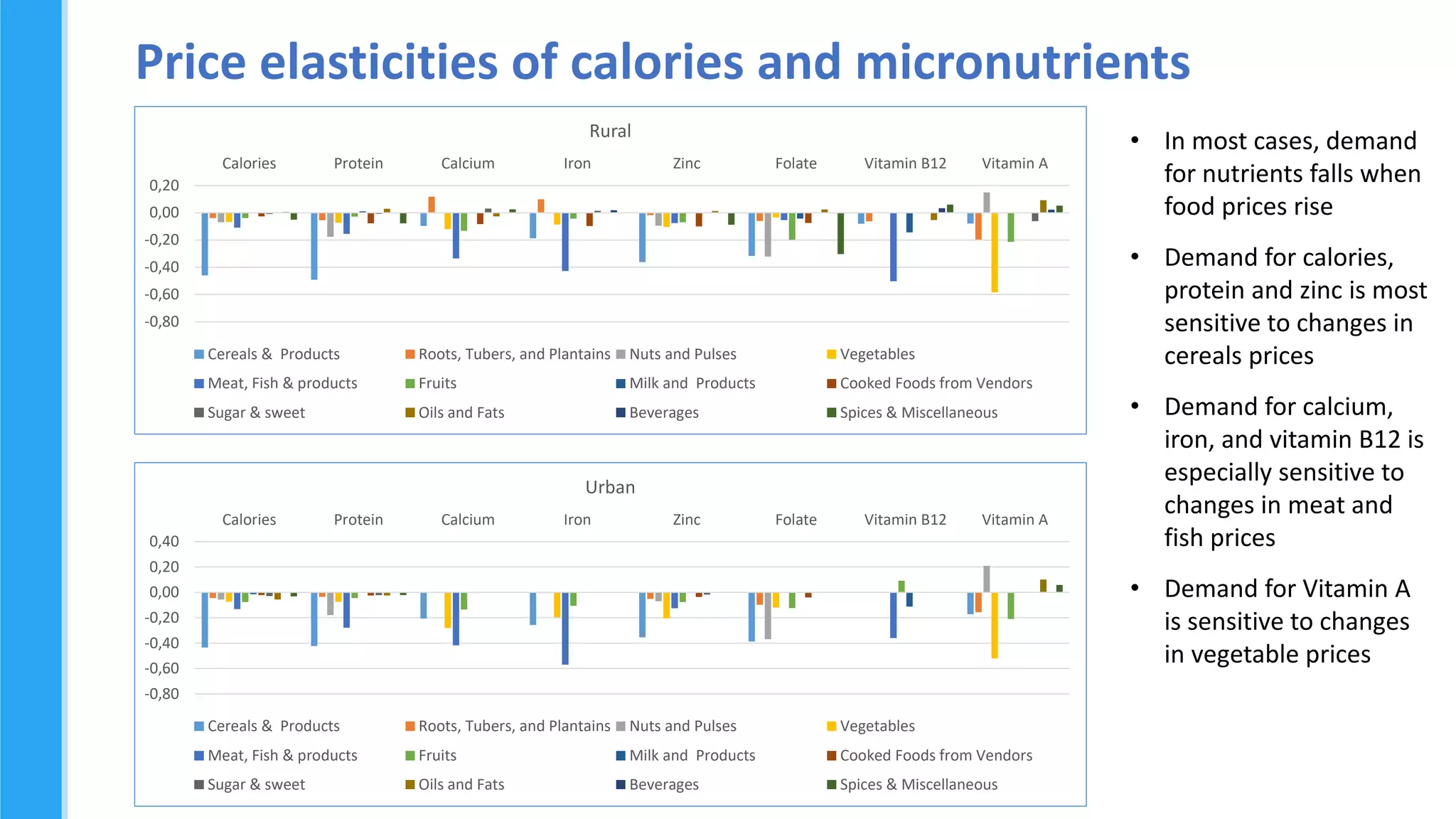

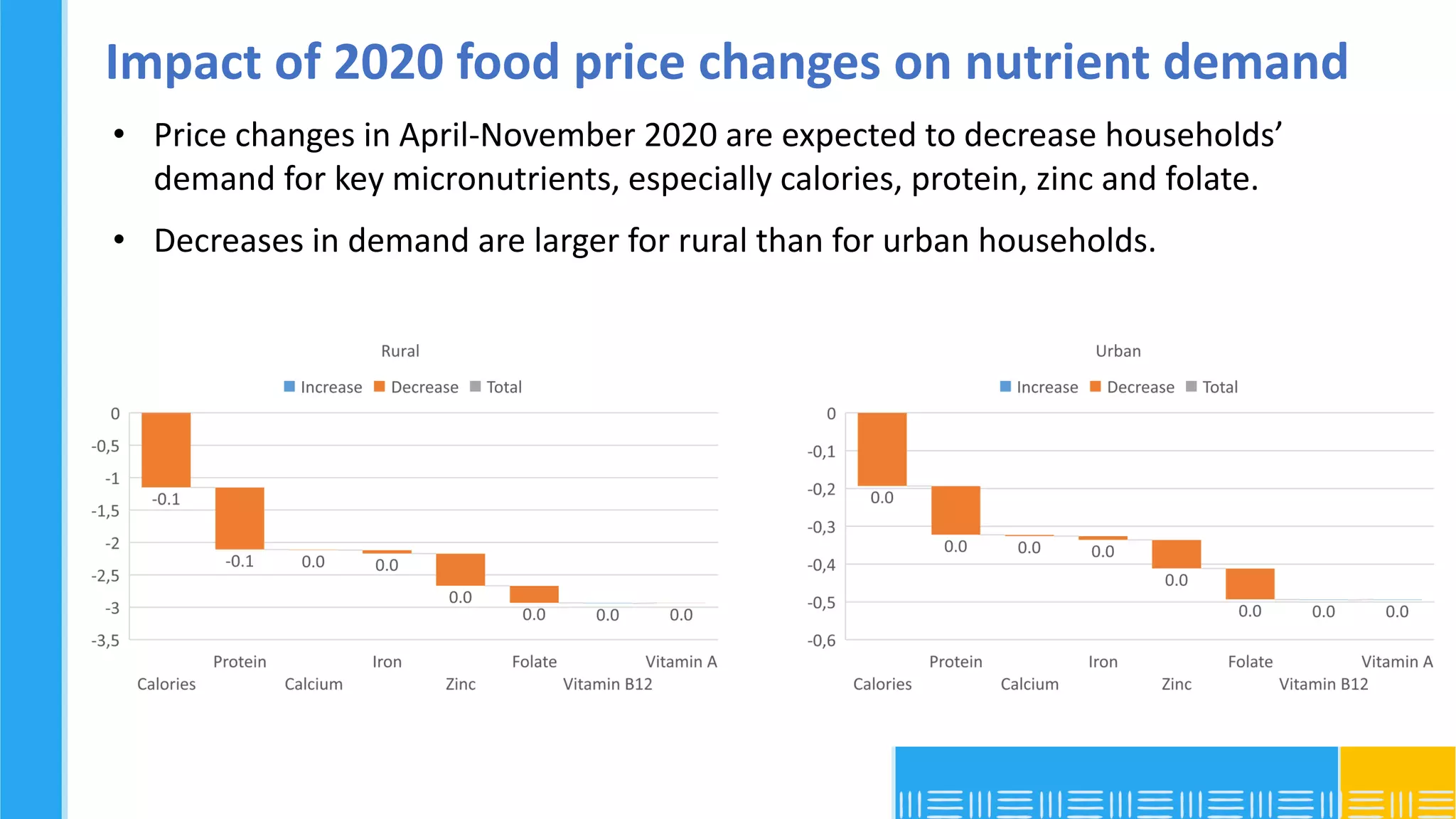

This document analyzes community vulnerability to COVID-19 in Malawi using spatial data. It finds the Southern Region and several districts within have the highest overall vulnerability due to factors like high stunting rates, low food expenditures, and poor access to healthcare. Urban areas like cities face high vulnerability from population density. Food price changes in 2020 decreased demand for key micronutrients in both rural and urban households, with a larger impact on rural areas, potentially exacerbating existing micronutrient deficiencies. The analysis identifies priority areas for crisis prevention and mitigation based on chronic vulnerability.