The document discusses the right to education as a fundamental human right highlighted in international frameworks, emphasizing its role in sustainable development and poverty reduction. It outlines the challenges Nigeria faces in achieving educational access due to chronic underfunding and exacerbated issues from the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly affecting girls and marginalized populations. Recommendations include amending the Universal Basic Education Act to expand educational provisions, increasing budget allocations for education, and ensuring community involvement through school management committees.

![15

References

1

Universal Basic Education Commission (2018) 2018 Digest of Statistics for Public Basic Education Schools in Nigeria.

https://www.ubec.gov.ng/media/news/526415d9-ed64-46cd-a2b1-659a26d66507/

2

The Guardian Nigeria (2018) Article: Nigeria accounts for 45% of out of school children in West Africa, says UNICEF

https://guardian.ng/news/nigeria-accounts-for-45-out-of-school-children-in-west-africa-says-unicef/

3

States with the most out-of-school children are Benue, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Sokoto, Taraba, Yobe and Zamfara states in the North and Akwa Ibom, Ebonyi and

Oyo states in the South. Unicef (2018) Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2016-17: National Survey Finding Report.

https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/media/1406/file/Nigeria-MICS-2016-17.pdf.pdf

4

Premium Times (2019) Article: Eight million out-of-school children in 10 Nigerian states and Abuja – UNICEF.

https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/335352-eight-million-out-of-school-children-in-10-nigerian-states-and-abuja-unicef.html

5

Ibid.

6

UNESCO-WIDE (2020) Indicator: Never been to school. Country: Nigeria. Year: 2013.

https://www.education-inequalities.org/countries/nigeria/indicators/edu0_prim#?dimension=all&group=all&age_group=|edu0_prim&year=|2013 [accessed 11 May 2020]

7

Gordon, R., Marston, L., Rose, P. and Zubairi, A. (2019) 12 Years of Quality Education for All Girls: A Commonwealth Perspective.

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2542579/

8

Malala Fund (2020) Girls’ education and COVID-19: What past shocks can teach us about mitigating the impact of pandemics.

https://downloads.ctfassets.net/0oan5gk9rgbh/6TMYLYAcUpjhQpXLDgmdIa/3e1c12d8d827985ef2b4e815a3a6da1f/COVID19_GirlsEducation_corrected_071420.pdf

9

UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (2003) General comment no. 5: General measures of implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, paragraph 7.

https://www.refworld.org/docid/4538834f11.html [accessed 3 August 2020]

10

UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1990) General Comment No. 3: The Nature of States Parties’ Obligations, paragraph 11.

https://www.refworld.org/docid/4538838e10.html [accessed 3 August 2020]

11

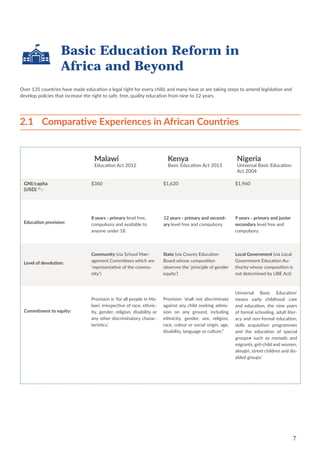

World Bank Data (2020) Indicator: GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$). Country: Malawi, Kenya, Nigeria. Year: 2018.

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD?locations=MW-KE-NG [accessed 11 May 2020]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/makingtheuniversalbasicprint-201008091921/85/MAKING-THE-UNIVERSAL-BASIC-ACT-WORK-FOR-ALL-CHILDREN-IN-NIGERIA-15-320.jpg)