MagazineNOBLEED.compressed

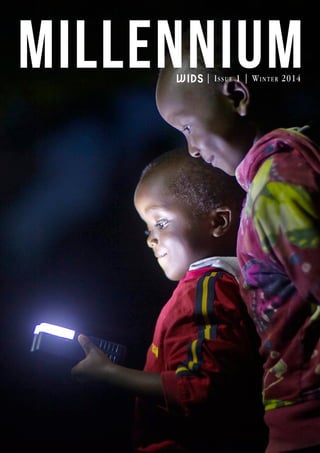

- 1. MILLENNIUM | Is sue 1 | Winter 2014

- 2. Editor’s Letter Welcome to the WIDS M a g a z i n e ! We are proud to be publishing the first edition of our bi-annual magazine se-ries. Millennium is the only published magazine on campus that solely focuses on development issues. Indeed, WIDS is the only development-fo-cused Society on cam-pus. We are therefore very excited to provide the Warwick community with an outlet to read and write about current events and trends in the field of development that are important to us stu-dents! Whether you are reading this magazine as a member of the Socie-ty or just an interested student, remember that issues of development are relevant to us all. As citizens of the world we should all be concerned with the social and eco-nomic progress of de-veloping countries. As students at an ambitious university such as War-wick, these issues are es-pecially relevant to you, as whatever career you choose to pursue will no doubt place its work within a global context. In this issue we have embraced this year’s theme of appreciating development through the lens of diversity. We therefore have articles that focus on a variety of countries, and the magazine is split into the following geographi-cal regions: Africa, Asia, MENA, Latin America as well as the more devel-oped parts of the world. We are also exploring diversity in terms of the different sectors that affect development, so look out for articles that focus on medicine, jus-tice, gender equality, governance and econom-ic inequality just to name a few. As we’re fast ap-proaching the deadline of the eight Millennium Development Goals, we have a special section on how far we’ve come in terms of achieving these targets. Hence, alongside our Summit, we aim to look to the Post-2015 De-velopment Agenda and the future of develop-ment as a whole, to truly explore what more needs to be done. We would like to thank all of our writers for putting in their time and research to write ar-ticles on issues that were important to them. We had contributions from people on courses from History and Literature to Politics and Econom-ics, and we feel this has given Millennium a real-ly broad relevance and appeal. Thanks also to my editing team, Luksha Wickramarachchi, Daisy Sibun and Iris Karaman, as well as our Creative Director, Hiran Adhia who single-handedly de-signed the entire maga-zine, and the rest of the Executive Committee for supporting us in the Mil-lennium’s production. We hope you enjoy the magazine and that it inspires you to engage with issues of develop-ment in the future. Hap-py reading! Alexandra Karlsson Editor-in-Chief MILLENNIUM’S PRODUCTION TEAM Alexandra Karlsson Editor-in-Chief Hiran adhia Creative Director Luksha Wickramarachchi Editor iris karaman Editor daisy sibun Editor THE WIDS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 2014/15 Co-coordinators & Presidents Stephanie Ifayemi Riko Yamada Secretary Jason Tran Treasurer Rahima Chairi Events Cindy Asokan (Head) Adeorike Oshinyemi (Deputy) Design Hiran Adhia (Head) Marketing Zara Yaqoob (Head) David Henning (External) Balzs Vincze (Internal) Media Luksha Wickramarachchi (Head) Alexandra Karlsson (Magazine) Daisy Sibun (Deputy) Operations Atif Jeelani (Head) Lubna Al Ariqi (Hospitality) Bhavin Ashra (Hospitality) Nahal Darvia (Logisitcs) Sponsorship Karan Thakrar (Head) Kulani McCartan-Demie (Deputy) Yulu Wu (Deputy) Talks Ibtehal Atta-Elmanan (Head) Aashna Jaggi (Deputy) Iris Karaman (Deputy) Partnerships Oluwatito Olaniyan (Head) Yeong Lee (Deputy) Anushay Neeshat (Deputy) Noshin Suleman (Deputy) Fresher’s Representative Christina Stuart Postgraduate Representative Selin Koksal Jonathan Menary “ Our human compassion binds us the one to the other - not in pity or patronizingly, but as human beings who have learnt how to turn our common suffering into hope for the future.” Nel son Mandela

- 3. The Warwick International Development Society is the University of Warwick’s forum for discussing issues of development. We hold an annual three-day Summit that is the largest of its kind in the United Kingdom! The Summit sees dis-t i n g u i s h e d leaders in the field of develop-ment speaking on current issues around a specific theme. This year’s theme is Development Through the Lens of Diversity, so we will be welcoming speak-ers from a variety of backgrounds, includ-ing medicine, archi-tecture, transparency, NGOs and the United Nations. Our goal is to en-gage as many stu-dents as possible in the world of develop-ment. As such, the So-ciety also hosts a Lec-ture Series that runs throughout the year following the sum-mit, as well as various exclusive internship opportunities. More details will be made available in the weeks following the Sum-mit. We will also be publishing another magazine in the sec-ond term, so look out for more writing op-portunities and other ways to get involved in our dynamic Soci-ety? Make sure to con-nect with us through our social media on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. @WIDS_2014 C O N T E N T S EDITOR’S LETTER 3 WARWICK INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT SUMMIT - Development Through the Lens of Diversity 4 LATIN AMERICA - Is the Chilean Education System a Success Story? 7 - Latin America: The Miracle of the Millenium Generation? 8-9 - Alianza del Pacífico vs. Mercosur: which is the best model for development? 10 ASIA - Building From The Ground Up in Asia 13 - The Fruits of Prosperity are spread unevenly 14 - The Chinese Contradiction 15 - An Unclean Bill of Health in India 16-17 CENTRESPREAD - Millennium Goals: Less than 500 Days to Go 18-19 - A Time For Change...a new BRICS Development Bank 20-21 AFRICA - On Rough Seas: Why Somalian Fisherman Turn to Piracy 23 - Why is Africa poor? Looking Back in History 24-25 - My Phone Fuels a War 26 - Biofuel in Best Practce: The Makeni Project, Sierra Leone 27 MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA - Transitional Justice and its Role in Development 29 - The Two State Solution with One State Economy 30 - Why Middle Eastern Women do not need White, Western Feminists 32 DEVELOPED WORLD - Profile of An African King 34 - Celebrity Feminism: A Fashion for Inaction or Glamourizing Change? 36 PARTNERSHIPS & INTERNSHIP OPPORTUNITIES 38 SPONSORS 39 4 5

- 4. is the CHILEAN education system a success story? On paper, Chile has been one of the great development suc-cess stories in Latin America, appearing on course to become the continent’s first de-veloped country. Statistically, poverty rates have been slashed dramatically over the past few decades, GDP per capita growth has averaged over 3% a year, infant mortality rates have plummeted and life ex-pectancy has soared. The country has seen itself catapulted into the World Bank’s league of “high-in-come countries”. Education sta-tistics are especially encouraging, with the gross primary enrolment rate at virtually 100% and the gross secondary enrolment rate close to 90%. Impressively, ab-solute poverty is close to being eradicated; according to the most recent Casen survey just 2.8% of Chileans now live in absolute poverty. This success story is the re-sult of sensible macroeconomic policies, the first of which was the promotion of free trade: Chile has signed more free trade agree-ments than any other nation, and is also a founding member of the Alianza del Pacífico (Pacific Alli-ance) trading bloc. The country has embarked on the privatisation of many formerly government owned companies and the liber-alisation of financial and prod-uct markets, allowing the private sector to play a large role in the economy. The central bank enjoys complete independence and the government has been prudent with regards to spending. Dur-ing the commodities boom of the early 2000s for example, the government used the extra reve-nue from increasing exports to set up two sovereign wealth funds, the Pension Reserve Fund and the Economic and Social Stability Fund. It was then able to engage in counter-cyclical fiscal spending and call on these reserves during the recent recession. The Chile-an experience could suggest that the policy mix for development is deceptively simple; allowing free trade, embarking on privatisation and liberalisation of markets, con-ducting prudent fiscal policy and independent monetary policy will cause growth to occur and pover-ty rates to fall. Yet a crucial point can be overlooked by studying macroe-conomic figures alone: Chile is afflicted with one of the worst degrees of economic inequality in the world. The country’s Gini coefficient, a measure of inequal-ity, was 0.52 in 2009 (the average rate in contrast is just over 0.3), and has remained stubbornly high over recent decades. In the rank-ing of HDI by country, Chile falls a staggering 16 places once ine-quality is taken into account. One particularly startling figure which demonstrates the inequality gap is that the richest 10% of the Chil-ean population account for more than 40% of the country’s wealth. The poorest 10% in contrast are responsible for a mere 1.7%. The divide between rich and poor is stark. It is clear to see that a small group at the top have reaped most of the benefits of Chile’s econom-ic growth, while the majority of the population has been left be-hind. One key factor driving the di-vide between rich and poor is the Chilean education system, which according to UNESCO has caused “segmentation, exclusion and dis-crimination”. The system is mar-ket- orientated and decentralised. Although the figures of enrolment rates are impressive, they do not reflect the poor quality of the ed-ucation being provided. Although getting more students into class-rooms is a worthy achievement it is also vitally important that they are taught well. There is a large gap between the educational at-tainment of students attending municipal schools and those who go to private schools. In the most recent SIMCE, a test which meas-ures proficiency in English, 81% of private school students passed the test compared to only 7% of municipal school students. This huge disparity can be explained by multiple factors, including the fact that municipal schools have larger class sizes than their pri-vate counterparts. Furthermore municipal schools are poorly funded and crucially have worse teaching standards, as many of the best teachers tend to flock to private schools where they are offered higher wages. Too many universities also suffer from poor quality teaching and offer cours-es with little value in the labour market. Another aspect of the Chil-ean education system which has perpetuated inequality is its cost. For primary and secondary schools a system of co-payment exists, whereby private schools can top-up the vouchers they re-ceive By Ol iver Reynolds by charging tuition fees to students. This has the effect of ex-cluding some students from poor families from the best schools. Higher education is also exceed-ingly expensive; tuition fees rela-tive to GDP per capita in Chile are among the highest in the world according to the OECD, making it difficult for poor families to afford to send their children to university. The combination of the poor quality and high cost of education in Chile stunts social mobility and shackles the country’s econom-ic potential. The country has a small, well-educated and highly productive elite who study at the top private schools and universi-ties, consequently enabling them to secure well-paid jobs and enjoy a high quality of life. Conversely, a larger proportion of the popula-tion, one that is poorly educated and have fewer skills, languish in an economically precarious sit-uation. Even if Chile eventually catches up with developed coun-tries in terms of GDP per capita, it must achieve a more equitable distribution of its wealth in order for its citizens to enjoy the living standards of a developed country. Thankfully, there are signs of change. The number of grants of-fered by universities has increased dramatically in the last few years, allowing more students from poor backgrounds to access higher education. Perhaps more impor-tantly, current president Michelle Bachelet, has recently announced a reform package which amounts to the biggest shakeup of the ed-ucation system in decades. One of the key elements of these ed-ucational reforms is that primary and secondary education will be made free for everyone. Although this is undoubtedly a step in the right direction and will reduce the socioeconomic segregation in the education system, the reform does little to tackle the problem of poor quality education. Passing reforms to make education free will not improve the standard of teaching in classrooms. The prob-lem of inequality can only truly be solved when Chileans from right across the socioeconomic spectrum are all able to enjoy the same quality of education. If the government is able to make ad-vances on this front, then Chile will finally be able to combat its deep-seated economic inequal-ities and become the first devel-oped country in Latin America. Credit: Flickr / perropatata LATIN AMERICA “The region of Latin America and the Caribbean has achieved parity in primary education between boys and girls, and it is the only develop-ing region in which gender disparity favours girls in both secondary and tertiary education.” Credit: Flickr / mmwhortgroup Latin America | 7

- 5. 8 |Latin America 9 With the Millennium Development Goals deadline approach-ing, we become more and more interested in the results. Who has succeeded? Which countries managed to in-crease living standards, develop and prosper? China, India and Brazil are commonly listed as examples with very impressive economic growth. If we address these questions not to countries but to regions, South America is often mentioned as a territory with relatively equal lev-els of decent economic growth while most attention is paid to the “failed states” of East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. However, in this article, the focus will be on the Latin America, the region that has managed to make noteworthy progress but still has a long way to go. The average growth rate of the region during the last decade was 4%, which gives a period of 18 years needed to more than double the economy. New urban areas were built with better living conditions for families. Countries like Brazil, Chile, Columbia and Venezuela are currently classified as upper-middle countries, while all other countries with the excep-tion of Haiti are middle-income. Referring back to the develop-ment goals, the first one is to end extreme poverty. Latin America seems to succeed in this too. The World Bank in 2011 announced that for the first time, more peo-ple were classified as middle-in-come in this region rather than in poverty. This is a commendable achievement. However, there is anoth-er important fact that is not so broadly discussed. The Econom-ic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) an-nounced in 2011 that Latin Amer-ica is the region with highest ine-quality in the world. For instance, Carlos Slim Helu, who according to Forbes was the richest man in the world for four years, lives in Mexico; where 52.3% of the popu-lation live below the poverty line. UNICEF (2008) published GINI coefficients of 0.48 for the region in comparison with the world’s average of 0.397. What is even more striking that the GINI In-dex in Haiti was 0.59, Colombia: 0.58 and Brazil: 0.55, while the countries with the lowest inequal-ity in the region were Venezuela: 0.43 and Uruguay: 0.46. All of the figures are well above the world average with the majority of their local populations facing even higher levels of inequality. There-fore, the crucial question is how inclusive is economic growth? Is there equal development across all levels: across the countries in the region, both in rural and ur-ban areas, and between genders? First, let us address the un-even development across coun-tries. The region is considered middle-income by the UN. How-ever, it also groups countries by poverty levels: very high, high, middle and low extreme pover-ty. Unfortunately, Latin America is represented in every class. In the ‘very high’ category there is Guatemala, Honduras, Nicara-gua, Paraguay and Bolivia, where 30% of the population is trapped in extreme poverty. In the ‘high’ group, which includes Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador and El Salvador, it is 14.5%. That gives us precisely half of the coun-tries with very high and high ex-treme the millennium generation? poverty in a middle-income region. A similar situation may be observed on a domestic level. Lat-in America is one of the most ur-banised regions in the world, with 80% of population living in cities (in comparison with Europe’s average of 73%). Both rural and urban areas experienced poverty reduction and extreme poverty numbers dropped. Yet, Brazil has about 20 million poor people in rural areas out of about 28 mil-lion whilst three out of four rural people in the Andes live under the poverty line. On a domestic level the poverty in the villages did de-crease, but not as much as can be thought at first sight. Moreover, even in the cities the inequality is striking. Over 111 million Latin Americans live in shanty towns. In most coun-tries, formal housing is unaf-fordable for the majority of the population with this figure at 70% in Brazil and Mexico. Such vast inequality also increases crime rates and violence in urban areas which imposes a huge extra cost on to the government, such as in Colombia, where crime costs account for around 25% of the country’s GDP. Therefore, despite the level of urbanisation the pov-erty is still there. It seems like it has just moved from the villages to the cities. What about gender equality? This aspect might seem odd to even discuss in the region consid-ering the three female presidents of Brazil, Argentina and Costa Rica. Moreover, between 1990 and 2008, the average female partici-pation rate in Latin America grew by more than 10% in non-agri-cultural sector. However, if these numbers are looked at more care-fully, the women who join the work force have lower education levels and are paid less. Although in labour-intensive work, wag-es are equally low for men and women, for women with higher education, the wage gap remains significant. Moreover, despite the empowerment of women in Latin America, 34.4% of women do not have their own income compared with 13.3% of men. It appears that gender inequality still persists, just more covertly. It is important however to state that these problems do not undermine significant progress made by collective efforts of governments and international organisations in the region. For instance, countries like Mexico, Brazil, Panama and Chile have im-plemented so-called conditional cash transfers. The idea is to give financial aid to poor families on the provision that the money will be used as an investment in the health and education of their chil-dren. In the ECLAC report on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, the first goal was also to reduce inequality gaps in the region. The issue of exclusive economic growth seems to be addressed on all levels starting from regional (equal economic growth across all countries), domestic (equal living standards in urban and rural are-as) and up to the individual (eth-nic and gender equality). Hence, it is clear that it takes time and effort to become a mid-dle- income region, but this ‘title’ does not eliminate problems; it is just an opportunity to overcome new challenges. Latin america: the miracle of By Pol ina Skladneva Credit: Flickr / worldbank + IICD

- 6. Alianza del Pacífico vs. Mercosur which is the best model for development? Latin America as a whole has experienced impres-sive development over the last decade, with pov-erty rates falling substantially and growth accelerating. Two of the continent’s largest trading blocs pushing this development are Alianza del Pacífico (Pacific Alli-ance) and Mercosur. The Pacific Alliance, current-ly made up of Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru, was formed as late as 2011. It has stated its aim as simply to promote trade and economic integration among its members. Mercosur on the other hand, founded back in 1991, has declared a much grander aim; it intends for its members to form a union that is not just economic but also political, similar to the European Union (EU). The two alliances are radical-ly different in their approach. The economies of the Pacific Alliance are far more outward-looking and export-orientated. Merchan-dise exports for all of the bloc’s members apart from Colombia are over 45% of GDP, a rate of exportation that is significantly higher than that in the countries of Mercosur. The Pacific Alliance has moved rapidly to remove trade barriers between member countries; over 90% of tariffs have already been abolished. All of the bloc’s members have signed trade agreements with important trad-ing partners such as the US and the EU. In addition, three of the four members of the Pacific Alli-ance (Chile, Mexico and Peru) are in talks with other countries in the Americas and Asia to create the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a proposed free trade zone which would be the largest of its kind in the world. Mercosur on the oth-er hand has signed only two free trade agreements in the last ten years, one with Israel and the oth-er with the Palestinian Authority. Talks with the EU to attempt to sign a free trade agreement have dragged on for over a decade. In recent years, far from reduc-ing tariffs, Mercosur has instead turned to protectionism. The maximum common external tariff to be imposed on goods imported from outside the union was in-creased to 35% in 2012. A clear distinction between the two blocs is that the Pacif-ic Alliance economies are far more liberal than their Mercosur counterparts. Industry in these countries is largely privatised and governments play a much smaller role in the economy preferring to allow market forces to dictate growth. The Mercosur economies in contrast are heavily regulated with a high level of economic in-terference from the government, something that has only tended to increase in recent years. A prime example of this is the Argentini-an government’s expropriation of YPF, the Spanish-owned oil com-pany. In the last few years Vene-zuela has also nationalised its oil industry as well as other sectors of the economy such as telecoms. The two blocs have enjoyed varying levels of success in reduc-ing poverty over the past decade. Data from Cepal (a branch of the United Nations) shows that on average the proportion of people living below the poverty line in the Mercosur countries fell from 35.9% to 20.6% between 2005 and 2012. The corresponding fall in Pacific Alliance countries was from 36.2% to 32.4%. This far more modest reduction in the poverty rate is due to the fact that pov-erty actually rose in Mexico over the period, negating a large part of the gains made in Peru, Chile and Colombia. Mercosur’s recent success at reducing poverty, as well as the Pacific Alliance’s rel-ative lack of it, can be explained to a large extent by the commodi-ties boom experienced in the first decade of the twenty-first centu-ry. Mercosur countries benefited hugely from this boom due mainly to their nature as large export-ers of commodities; growth rates remained consistently above 6% per annum during this period. High rates of growth filled their governments’ coffers, providing money to spend on redistributive social policies and resulting in the steep decline of poverty rates (the Bolsa Familia program in Brazil is a famous example). Mexico on the other hand, with closer economic ties to the United States and less dependence on primary products, was unable to benefit as much from the boom. The country expe-rienced slower growth as a result, largely cancelling out the fall in poverty experienced in the other three Pacific Alliance countries. By looking solely at past per-formance it could be assumed that Mercosur will continue to outper-form the Pacific Alliance in years to come. However, the commodi-ties boom that caused impressive By Ol iver Reynolds rates of growth in Mercosur ap-pears to have ended with no sign of returning any time soon. More-over, the Pacific Alliance countries possess more business-friendly environments and stronger links with fast growing regions like East Asia. A combination of these factors has led to hugely differing growth forecasts for the two blocs over the coming years. The predictions for Mercosur are pessimistic; the IMF foresees that growth in Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela will be low or even negative for the next two years. Conversely, growth in the Pacific Alliance countries has recently stormed ahead with a growth rate of more than 3.5% forecast for 2015. This pattern of lethargic growth in Mercosur countries and the contrasting dynamism of the Pacific Alliance looks set to con-tinue for the foreseeable future. If Mercosur countries are unable to grow then they will find it increas-ingly difficult to finance the social redistribution programs currently in place. Unemployment is also likely to rise, causing workers to lose income. Thus although Mer-cosur has achieved commendable progress in reducing poverty and promoting development in the last decade, it seems likely that there will now be a stagnation in terms of its economic devel-opment. Comparatively, the Pacific Alliance countries seem to be going from strength to strength. With their export-orientated, outward-looking economic mod-el they are well placed to ben-efit from continued growth in fast-growing regions such as East Asia. In addition, the possibility of signing the Trans-Pacific Part-nership could bring even more growth to its member countries. With higher growth should come greater employment opportuni-ties and more money to spend on social redistribution policies. This in turn is likely to cause a decline in poverty and begin to promote the broader economic develop-ment of Latin America. Although Mercosur has undoubtedly proved more successful than its counter-part in achieving economic devel-opment thus far, the future looks like it well and truly belongs to the Pacific Alliance. Credit: Flickr / CimmyT Credit: Flickr / rockandrollfreak + DFID 2015 MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS ERADICATE extreme 1. poverty AND HUNGER 2. achieve universal primary education Latin America | 10 11

- 7. building from the ground up in asia High rates of devel-opment are strongly correlated with high rates of urbanisation. In the regions with the most im-pressive economic growth, such as large parts of Asia, the num-ber of people living in cities has grown dramatically. Consequently, there has been an increase in the number of cities along with a rise in the respective populations and sizes of these cities. On the one hand, it is a positive sign that society is making progress by developing new industries (or creating them from scratch), improving trade and supporting small business-es. On the other hand, cities can cause environmental hazard and degradation. Rising rates of urban poverty have also been known to increase the rate of violence and crime in such cities. To solve this problem supporters of sustaina-ble development believe in the importance of small town devel-opment. Firstly, small town devel-opment will supply people with work at the places of their resi-dence so it is likely to solve the problem of overpopulated cities. Secondly, population growth in urban areas has been so fast and rapid that infrastructure has not managed to grow and adapt at the same rate. Inadequate infrastruc-ture is irrefutably linked with higher pollution and lower stand-ards of sanitation. Thirdly, it will support community development. In particular it might be benefi-cial to increase the quality and accessibility of education, thereby helping to provide more equal opportunities. Development will lead to the increase of living standards in an area and that in return will attract better teachers. The continent that is deal-ing with this issue the most is Asia. The specific problems that towns face depend on the coun-try. According to World Bank, for instance, the most urgent issues in Nepal’s small towns are sanita-tion and access to a clean water supply. According to Water Aid estimations (2010) only 5% of the population that live outside cities had access to piped water and sanitation coverage was only 36%. For China the issue is poor infrastructure. The country is very export-orientated so key factories were built on the eastern coasts and the majority of the workforce simply relocated there. This led to By Pol ina Skladneva the almost complete isolation of some small towns as it meant that the development of a transpor-tation system within the country was not deemed a necessity. For Russia the main problem is un-employment. Unemployment has affected a rise in the average age of small town populations, with young people being forced to mi-grate to cities in search of employ-ment. This trend of urbanisation falls especially hard on families leaving seniors with children without support. Fortunately, the problem has already been addressed. The Asian Development Bank is currently fi-nancing a project aiming to sup-ply clean water to distant areas of Nepal. The project was rated as effective with over 570,000 people gaining access to piped water. One-third of all the bene-ficiaries were women who would previously spend two hours a day transporting water during the dry season. Nepalese communities supported these changes and are currently sustaining those water pipes independently. In China the World Bank launched a scheme called The Integrated Economic Development of Small Towns Pro-ject at the end of 2012. It aims to construct and rehabilitate road networks, water supply and waste management. The project is cur-rently in progress and although it is too early to approximate its successes, the fact that the gov-ernment have recognized and addressed China’s infrastructure problem gives hope that eventual-ly it will be overcome. Moreover, in 2011 the World Bank complet-ed a successful project in the po-lar regions of Russia. They helped people to migrate from distant villages to the local centres. Re-markably, parents, husbands, wives and children were helped with the move as well. Development is not only a challenge in itself; new challeng-es often arise as a consequence of developmental efforts. Iden-tifying and dealing with these challenges is essential for max-imising sustainable development. Fortunately, governments and international organisations are appearing increasingly capable in facing and overcoming them. The main challenge appears to lie in departing from orthodox patterns and sourcing new solutions for unfamiliar problems. Credit: Flickr / monkeylikemind + nateluzod ASIA “Extreme poverty rates of people living on less than $1.25 per day halved in Eastern Asia and South-Eastern Asia, but Southern Asia needs more time. China leads the way in global poverty reduction, although it is still home to about 13 per cent of the world’s extreme poor.” Credit: Flickr / lain32 As ia | 13

- 8. Credit: Flickr / ramnaganat the fruits of prosperity are spread unevenly Since Deng Xiaoping lib-eralised China’s economy and opened it up to world trade in 1976, the Chinese Economic Miracle has made head-lines around the world. Averaging a remarkable 10% GDP growth and 6.6% income per capita growth for over three decades, China’s swift economic growth has undoubted-ly been extraordinary. However, these impressive figures mask a worrying trend. Development, not only on an individual but also increasingly a regional basis, is starkly unequal. China’s eastern regions, par-ticularly along the coast, are the main beneficiaries of growth. On the other hand, western China remains largely poor and undevel-oped. The Western Regions com-prise 71.4% of China’s land area but contribute merely 18.6% of its economic output. In compari-son, just eight of China’s eastern cities – Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Suzhou, Hangzhou and Qingdao – make up 20.2% of China’s GDP. According to The Economist, wealthy regions in China like Jiangsu and Zhejiang have econ-omies comparable to Switzerland and Austria respectively; mean-while, south-western Tibet has a smaller economy than Malta, de-spite being almost 8000 times its size. From 1990 to 2000, the GDP per capita of the Western Regions declined from 73% of the national average to 61%, with the province of Hotan in far western Xinjiang having a GDP per capita of just $1134 – below that of Zimba-bwe, which is widely considered a failed state. Clearly, the fruits of eco-nomic development since 1976 have been distributed very un-evenly in regional terms. The reasons for this can be broadly classified into geographical and political categories. From a geographical per-spective, eastern regions in China are much more fertile than their western counterparts. Agriculture has historically been concentrat-ed in the temperate Zhejiang and Jiangsu regions, through which runs the fertile Yangtze River Del-ta. As a result, these two regions have tended to contribute a larger portion to China’s economy. In contrast, western China contains vast stretches of desert wasteland, like the infamous Taklamakan, as well as the southwest which is arid and mountainous: the Qing-hai- Tibet Plateau lies 4000 metres above sea level and receives less than 200 millilitres of rainfall a year, a fifth of the world average. Such conditions necessarily ren-der China’s west and southwest less economically productive than the flatter and more fertile east. From a political perspec-tive, eastern regions in China have long been integrated within the country, while the western regions have historically been regarded as peripheral. This is in part because some of them were only incorporated into China dur-ing the Qing Dynasty. Moreover, their Uighur and Tibetan pop-ulations are ethnically distinct from the Han Chinese majority and resent Han rule, with the Ui-ghurs in particular being prone to rebellion. Economists generally agree that “peace, order and good government” is vital for economic development through trade and investment. Xinjiang has been the site of multiple genocides and ethnic cleansing attempts by both Han and Uighur, and, more recently, is plagued by sporadic outbursts of violence. Some Ti-betan inhabitants have taken to self-immolation to register their displeasure at being ruled from Beijing. In these two regions sta-bility and order are not easy to come by. Businesses have a much lower incentive and willingness to make long-term investments here. As a result, economic develop-ment is slower. The implications of une-ven economic development are deeply worrying. For the ethnic minorities in the Western Re-gions, poverty compounded with feelings of economic marginalisa-tion by the government fuel sep-aratist tendencies that threaten the territorial integrity of China. This is especially true for the mostly-Muslim Uighurs, who may increasingly turn to Islamic fun-damentalism. An Uighur separatist group, the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, is recorded to have committed over 200 acts of terror-ism between 1990 and 2001, and is included in the United States’ Terrorist Exclusion List. Unless ethnic minorities in the Western Regions see a prosperous future for their people inside China rath-er than outside it, separatism and terrorism will likely remain prob-lems for a long time. Furthermore, China’s east-ern regions are already overpop-ulated and polluted. Three of the world’s ten largest cities, Guang-dong, Beijing and Shanghai, are located in eastern China, and all three experienced a growth in population of 20% over the past 15 years. Large and densely pop-ulated areas tend to be prone to pollution: a Greenpeace report finds that in some parts of east China inhabitants suffer from air quality that is “very unhealthy or hazardous” for as much as a third of a year. Estimates by the Chinese government project that over the next 15 years a further 300 mil-lion rural inhabitants would move into cities. If economic growth and the jobs it brings continue to be concentrated in the eastern cities it will likely significantly de-teriorate the already-substandard quality of life and safety of the urban environment. Recognising these problems, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has begun to pay closer attention to the development of the western half of the country. By Wang Yihua The China Western Development Programme was launched in 2000 to increase economic growth in western China. Through a combi-nation of preferential tax policies for businesses, as well as direct fiscal interventions, the western regions saw investments in infra-structure and public utilities to-talling over £130 billion between 2000 and 2007. The programme achieved some signs of success: GDP per capita achieved an annu-al 13% growth rate and climbed back to 71% of the national aver-age this year. However, economic development in China typically brings environmental degradation and rising tensions due to social dislocation; this will be further complicated by problems of eth-nic unrest that aren’t as present in eastern China. The road to eco-nomic development in western China will likely be a winding and rocky one. In the long run, the question of whether the Western Regions can experience sustained growth depends on the CCP’s ability to balance economic development with not only environmental and social concerns, but also sensitive ethnic and religious tensions. With the Western Development Programme, the CCP has taken the first steps onto the right path. It remains to be seen, however, if it has the will and ability to con-tinue on this journey. THE CHINESE CONTRADICTION It is widely accepted that an important goal of any state is to achieve economic growth, with the underlying assumption that economic growth enables the state to fulfil one of its core functions: to maintain and improve the quality of life of its citizens. However, the recent experience of China represents an interesting case study where eco-nomic growth and welfare have, in certain ways, stood in contra-diction with one another. In achieving high levels of growth, China has focused on its ever-expanding manufacturing sector, which has led to various environmental problems, most notably the creation of hazardous levels of air pollution. The pur-suit of growth can in this sense be considered detrimental to welfare as it engenders adverse conse-quences, such as negative health and social effects, which stand in direct violation of the wellbeing of Chinese citizens. This uncovers an important trade-off between economic growth and welfare which is increasingly relevant given the rise to prominence of climate change and other environ-mental and sustainability issues. From 1990 to 2012, Chinese GDP grew by over 7%, with its manufacturing sector accounting for 59% of this increase. General-ly speaking, as standards of living are positively correlated to eco-nomic growth, this would suggest an improvement in wellbeing. Yet, as the Brundtland Commis-sion defined sustainable growth as “development that meets the needs of the present without com-promising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”, the Chinese pattern may not fit this trend, as coal accounts for about 70% of energy consump-tion – which as a non-renewable source, is unsustainable. Furthermore, this exploita-tion of coal has created hazardous levels of air pollution, so that 71 out of 74 cities monitored in China over 2013 did not meet the state environmental standards. This meant that a rare alert of “Or-ange” – the second highest in the four levels of urgency – was used in February 2014, triggering pan-ic buying of air purifiers and face masks, with many retailers in Bei-jing reporting that they had sold out stock during the city’s most recent bout of smog. In February, the PM 2.5 pollutant (those small enough to penetrate deep into the lungs and enter the blood-stream) reached 505 micrograms By Luksha Wickr amar achchi per cubic meter, which is 20 times higher than the level recommend-ed by the World Health Organ-isation. Thus, Beijing performs second worst in terms of living environment among 40 major cit-ies around the world, and is also, according to the Annual Report on World Cities, technically “un-inhabitable for human beings”. Hence, it is not surprising that a survey using the Personal Well-Being Index (PWI) and the Job Satisfaction Survey ( JSS) – which had shown to have good psychometric properties in pre-vious psychological research – found that cities with higher levels of atmospheric pollution tends to report lower levels of personal wellbeing. This result suggests that the personal wellbe-ing of China’s urban population can be enhanced if China were to pursue a more balanced growth path which curtailed atmospher-ic pollution. Therefore, although there is already a 35 Article Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Prevention and Control of At-mospheric Pollution in place, this may not be enough to battle the Chinese pollution. Hence, there needs to be recognition that the pursuit of rapid economic growth may not be the best way forward. However, Chinese represent-atives have highlighted on numer-ous occasions that the criticism raised by Western countries with regards to pollution in China is hypocritical because they have all gone through their own similar industrial revolutions in the pre-vious century. As these countries also created similar externalities before reaching their economic dominance as developed nations, it seems unfair that China is una-ble to do the same. Furthermore, some argue that the unprecedent-ed economic growth of China will ultimately make the country richer, so that they can tackle the side effects of this growth at a later stage. However, the growth of the Chinese middle class can still be considered a hindrance to environmental-friendliness, as in-creases in disposable income has led to monumental rises in energy consumption as well as purchas-es of automobiles, which further affect the pollution levels. Hence, it is clear that China sacrificed the environment in order to achieve breakneck economic growth, in such a way that the costs of this development may outweigh the benefits. 14 |As ia 15 Credit: Flickr / dshack

- 9. An unclean bill of health in india A year ago, my knowledge of India was cursory: it was the up and coming developing nation, the country where I trace my roots. Through the Internation-al Citizen Service (ICS), a UK youth initiative funded by DfiD, I worked with Raleigh Internation-al (one of five respected partner charities focused on youth-led sustainable development) for two and half months of grassroots de-velopment in a small tribal village named Soolebavi in Karnataka, South India. Now, I understand that India is the land of contra-dictions, where tourist laden rick-shaws groan past cattle herders as rockets fire into space, where the blight of ancestral caste, patriar-chal gender violence and vast ur-ban and rural inequality still mire the advances in disease preven-tion, access to primary education and burgeoning high tech and cul-tural centres of the second largest democracy in the world. Post development theory argues that development and aid are problems, not solutions. It posits that our ideas are Eurocen-tric and imposed and that they supposedly increase underde-velopment by hindering natural growth. In a post-colonial era it is important to remember that the rise of the Western youth’s interest in volunteering coincided perfectly with the change enacted by global neoliberal reform from the 80’s onwards. With large scale macroeconomic adjustment, heav-ily indebted countries became increasingly reliant on the global north through private, free mar-ket loans of loaded petrodollars. As the IMF and World Bank bailed out countries with concessional loans, with strings attached, it resulted in devalued currencies and further reduced governmen-tal intervention and spending in the education, healthcare and in-frastructure sectors. Living stand-ards deteriorated dramatically throughout the developing world, with its citizens bearing the brunt of the impact. Local NGOs and non-profits leapt at the promise of donated labour and resources, foreign volunteers were eager to ‘help’ and start up ‘alternative’ tourist companies were equally eager to capitalise by bridging both – resulting in the explosion of the volun-tourism industry and development capitalism. It is easy then to disregard my experience as just that, a self-aggrandising holiday of ad-venture and I certainly adhere to the stereotype. I would argue, however, ICS is different, an intel-lectually stimulating pilot of gov-ernment funded, youth focused, sustainable development, with enough oversight, infrastructure, resources and independent eval-uation to ensure it does not fall into the trap of being there for the sake of being there. Through my experience with Raleigh, with its laser focus on the MDGs, commit-ment to bespoke projects based on ground feedback and use of a diverse mix of six international and six national country volun-teers, I aim to provide a unique perspective on the latest results of India’s struggle to enact uni-versal reforms. Putting aside the obvious health implications, diseases are a major barrier to social and eco-nomic development. According to the annual evaluation report from the Ministry of Statistics, In-dia, the country is moderately on track in relation to the MDGs as trend reversal has been achieved for annual parasite incidence of malaria, prevalence of TB and HIV prevalence despite it increasing in certain states. My experience was initially not so optimistic. After the results of a Participatory Rural Appraisals where we interviewed individual households we found little to no knowledge of symp-toms and disease prevention and we set about creating practical, interactive information sessions, utilising drama, infographics, symbols and Q&As using the ba-sic information packs supplied by Raleigh. These took place at twilight on straw mats under the splayed light of a lone light bulb and torches outside the village leader’s house while refreshments – consisting of fruit/rations and our poor imitation of Indian black coffee (less sugar!) – were served. Additionally we introduced the concept of tippy taps – a sim-ple, hands free method of wash-ing one’s hands with soap using a jerry can/bottle, rope, soap and rock. I remember vividly the next day when we woke up to find a two children had built their own version. After a brief political struggle we also demonstrated to the youth committee how to fix their unfinished toilets and held dedicated sessions explain-ing their health and sanitation benefits. The in-village sessions climaxed in two large scale free health camps, dental and medical, held outside the village, both of which I co-organised to revolve around prevention techniques. Villagers visited interactive health stations, designed by volunteers and subsequently run by the vil-lage youth committee which we facilitated, before visiting the dentists or nurses for a check-up and/or basic treatment. Our short term objective were for attendees to fix loom-ing issues through treatment and begin to implement prevention knowledge. In the long term, we hoped the community would develop good practice in their daily routine and, like bacteria, pass knowledge both vertical-ly and horizontally, to children and peers respectively. Overall, the effectiveness and impact of our efforts is mainly anecdotal with issues legion. The results of pre and post surveys after health events show an increase in specif-ic knowledge about most diseases and ideas of good and bad food where cemented. We assumed the use of practical sessions to By Hasan Suida be more effective and the utili-sation of respected members of the community and mobilising the youth to deliver health mes-sages increased the likelihood of the future propagation of health prevention advice. For me, I dis-tinctly remember a moment while on a homestay with my favourite villager, Rangama, and elderly yet fierce and passionate individ-ual. After our meal by fire I can picture her washing it down with boiled water (repressing a slight cringe at the taste), taking the lid off a vat of water, pouring it into another in order to wash her hands, replacing the lid, removing the excess water and proceeding to brush her teeth away from sight with a toothbrush provided at the Dental camp. That night I slept well under the stars. Our impact on Soolebavi and their impact on us as individuals is impossible to truly measure. For me, our greatest benefit was providing the impetus to increase community integration and foster-ing a thirst for knowledge beyond what they already knew. These concepts aren’t on the post 2015 agenda or the new Rio 20 SDGs, they aren’t even measurable, but for me knowledge is power and social cohesiveness enables you to act on the information which you find useful. Despite its pitfalls, India has a bright future, its problems are not unsolvable. In a similar way, international development can be done wrong, especially when uti-lising youth who have no specific areas of expertise, but for me, in this case, despite issues – it was beneficial in different ways than expected. If we had any sustain-able impact on my brothers and sisters cultivating paddy in the summer sun, it was the cyclical and powerful widening of per-spectives that inspires myself and hopefully them to be more than they are. Perhaps that is a Euro-centric view, but I like it. Credit: Flickr / wethesolution + gofootloose + indianwaterportal 16 As ia | 17

- 10. MILLENnIUM GOALS tion, and hardly any progress has been made to reduce this trend, except in Southern Asia. India has seen a reduction from 600 women dying for every 100,000 births in 1990, to 200 by 2012. MDG #6 – combating HIV/ Aids, malaria, and other diseas-es – has been achieved. New HIV infections declined by 44% from 2001-2012, and 230,000 fewer children under 15 were infected with HIV in 2011 than in 2001. The success of the glob-al battle against HIV/Aids is due to the d r a - mat-i c i n - crease in access to antiretro-viral therapy for HIV-infected people, which has saved 6.6 million lives since 1995. As a result of this treatment, an increasing number of people are able to live with HIV. For instance in South Afri-ca in 1990, only 0.5% of people aged 15-49 were living with HIV and Aids. By 2003, that figure hit 17%, and has remained around this level. Moreover, there has been a 42% decline in the malaria mortality rate, due to a substan-tial expansion of malaria inter-ventions and funding. However, there is still progress to be made as 50 young women are newly in-fected with HIV every hour, and in 2012, malaria killed an estimated 627,000 people. This can be com-bated through increased access to treatment, and in increased education on preventing trans-mission. The world has met its targets of halving the population without access to safe drinking water and improving the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers. However, there remain other sanitation and environmental targets to achieve, leaving MDG #7 un-completed. For instance, 2.5 billion people do not have ac-cess to sanitation such as toilets or latrines, and 1 billion people still resort to open defecation despite increasing access to im-proved sanitation. Moreover, global emissions of carbon diox-ide have increased by over 46% since 1990, and nearly one third of marine fish stocks have been overexploited. Thus there remain steps to be taken in order to fulfil MDG #7, though the achievement of the water target is a large step towards ensuring environmental sustainability. In Afghanistan, for example, only about 5% of peo-ple had access to improved water sources in 1990; by 2011 this fig-ure reached over 60%. The eighth MDG is to cre-ate a global partnership for development; this goal is aimed at developed and developing countries. The achievement of this goal is fundamental as a platform for the other goals, and it highlights that developed countries are not doing what they could, and promised, to do at the Millennium Declaration. For instance, although official devel-opment assistance hit a record high of $134.8 billion in 2013, aid has shifted away from the poor-est countries, where attainment of the MDGs is the lowest. This indicates that motives for aid are often not based on the greatest need but on political, economic or strategic concerns. Since 1970 the international target for official development assistance is 0.7% of the donor country’s gross nation-al income. Although this was orig-inally conceived of as a minimum commitment only six countries have ever met the target. Britain first met the target in 2013, and the only other countries that have met it, in order of highest ODA/ GNI, are Norway, Sweden, Luxem-bourg, and Denmark, with Britain giving the lowest percentage out of the five countries. As the end date for the MDGs approaches, the UN is giving people a voice on the post-2015 agenda through a platform called “World we want 2015”, which en-courages global engagement with the future of international devel-opment. So far over five million people have voted on what issues matter most to them on: http:// vote.myworld2015.org/. The new set of goals that is currently be-ing developed and decided on will be called the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and 17 goals have been announced, though not finalised. They will in-clude the MDGs’ themes of ending poverty and hunger and improv-ing health, education and gender equality, as well as specific goals to reduce inequality, make cities safe, address climate change and promote peaceful societies. Cru-cially, the next set of goals will be universal, meaning all countries will be required to consider them when crafting their national pol-icies. Officially, the eight MDGs were applicable to all but they have been marketed as anti-pov-erty goals for poor countries that are funded by more developed nations. The whole world will be involved in the attainment of the SDGs, making it all the more necessary for everyone to engage in the global conversation on the post-2015 development agenda. At we entered into the new millennium, every member state of the United Nations com-mitted to the set of eight goals by signing the Millennium Declara-tion. These Millennium Develop-ment Goals (MDG) had an ambi-tious, yet achievable, deadline for the end of 2015. Having passed the 500 days-to-go mark, it is time to start critically evaluating what has been achieved and where, and what the future of the global de-velopment agenda will be. Ban Ki Moon described the MDGs as “The most successful global anti-poverty push in histo-ry”. The MDGs have indeed suc-ceeded in unifying states in the quest for their achievement, and creating a culture of purpose in the fight against extreme poverty and other developmental goals. Through the 21 targets and 60 indicators within the eight goals, the MDGs have focused policy on broader measures of develop-ment, yet also made abstract ide-as quantifiable. There have been numerous positive achievements, with four MDGs already achieved. However, the glass is also half empty considering four have re-mained unachieved, and success varies dramatically across the de-veloping world. The first MDG was to halve extreme poverty and hunger; this goal was met 5 years before the 2015 target. In 1990 an esti-mated 47% of people in develop-ing countries were living on less than $1.25 a day, and by 2010 this fell to 22%. Although the target has been met, it is still unaccept-able that 1.2 billion people live in extreme poverty, and more than 99 million children under five are still undernourished and underweight. The rate of progress is also slowing; for example, in Bangladesh from 1994 to 2002 the proportion of undernourished people fell from 38% to 16.4%, whereas from 2002 to 2011 it has only fallen to 16.8%. Moreover, the early success of this MDG is partly due to China’s dramatic progress, rather than a collective reduction in absolute poverty across the developing world. The second goal, achieving universal primary education, has not yet been reached, although enrolment has reached 90% in de-veloping regions. High dropout rates remain a major impedi-ment to MDG #2, as one in four children in developing regions who enter primary school are likely to drop out. Moreover, half of the 58-million primary school-aged children that do not attend school live in conflict-af-fected areas. Although Asian countries have been especially successful at increasing school attendance (the enrolment rate in Laos increased from 59.4% in 1992 to 97.4% in 2011), the goal is unlikely to be met. The world has achieved gender equality in primary ed-ucation; meaning MDG #3 has officially met its target. Howev-er, this equality does not continue through all levels of education. Most regions have gender-par-ity index scores of 0.97 to 1.03. For example, in Southern Asia in 1990, only 74 girls were enrolled in primary school for every 100 boys, and by 2012, the enrolment ratios were the same. However, women still face discrimination in access to higher education levels, secure employment, and partic-ipation in decision-making. The average share of female members in parliaments worldwide was just over 20 per cent in 2013. Global-ly, women hold on average 40 out of 100 wage-earning jobs in the non-agricultural sector; and the jobs they do hold are less secure and with fewer social benefits. The child mortality rate has almost halved since 1990; however, we still have not reached the MDG #4’s target to reduce child mortality by two thirds. 17,000 fewer children are dying each day since 1990, and measles vaccinations have helped to prevent nearly 14 million deaths from 2000 to 2012. In Ni-ger, for example, nearly a third of children under five died in 1990, this ratio had fallen to one in eight in 2011. However, prevent-able diseases are the main cause of under-five deaths, and further action needs to be taken to tackle this unnecessary loss of life. De-spite progress towards the goal, four out of every five deaths of children under the age of five continue to occur in sub-Saha-ran Af-rica and South-ern Asia. P r o - gress towards MDG #5, to improve maternal health, is falling far short of its targets. The maternal mortality ratio has fallen by 45% from 1990 to 2013, but this is not close to the target reduction of 75%. Currently only half of wom-en in developing regions receive the recommended minimum of four antenatal care visits. A ma-jor failure in the commitments to this goal is the lack of funding for family planning and reproductive health care. Moreover, high ado-lescent birth rates are perpetuat-ed by poverty and lack of educa- By Chri stina Stuart LEss than 500 days to go Credit: Flickr / usaid_images + minoritenplatz8 + unamid_photo + Un_PHOTO + cgiarclimate + DFID + flixel 18 |Centrespread 19

- 11. The BRICS – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – have as much to gain politically as they do economically from the es-tablishment of their own financial institution. Whatever the agenda, it signals a step in the right direc-tion for the cause of development. Plans for a New Develop-ment Bank (NDB) to be created by the emerging powers were ad-vanced at the sixth annual BRICS summit held in the Brazilian city of Fortaleza on 14-16th July 2014; not a moment too soon. The move to establish the financial might and independence of the emerging powers’ economies will endeavour to provide a healthy challenge to the conventional Eu-ro- American financial institutions that already monopolise the glob-al economy. The move is ambitious for a coalition of relatively dispa-rate countries and it is certainly likely that the scope of progress it can achieve in the field of development may be limited. Nonetheless, it is about time that emerging smaller economies are empowered to leave their own mark on the global economy and, ultimately, any united develop-ment effort should be celebrated. The initial start-up capital of $50 billion, an amount that is hoped will eventually reach $100 billion, will be split between the five participating countries. Fol-lowing a decision at the recent summit, the NBD will be based in China with its headquarters located in Shanghai. It was also announced that the institution will have an Indian president, a Russian Board of Governors Chair and a Brazilian Board of Directors Chair for the first six years. Hav-ing such senior positions filled by a broad array of executives with such diverse national interests and styles is sure to confront the bank with its fair share of diffi-culties. The important aspect to focus on, however, is the crucial attempt that the NDB represents in providing an alternative future for the global financial order. The creation of a NDB is in-tensely symbolic for the role of emerging powers on the global financial arena. The Internation-al Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank have dominated the financial stage for the past sev-en decades since their formation by the allied nations after World War Two. They were created to cater to the exponential increase in globalised trading relation-ships and to construct a stable and open global economy in the aftermath of another internation-al war. While these institutions were not founded only by Western countries, Europe and the United States have nonetheless held a sustained and significant influ-ence over negotiations and deci-sion- making ever since. The IMF is traditionally led by a European whilst the World Bank is led by an American executive. Of course, it is undeniable that these two lead-ing institutions are an impres-sively influential and expansive embodiment of the globalisation process. The fact remains, how-ever, that as long as a few ‘great’ powers hold the reigns over the most powerful institutions, eco-nomic inequalities will. A new and fresh financial institution is long overdue – not least because the devastating impact of the 2008 financial cri-sis has crucially undermined the post-war international financial order. The 2008 crisis was aggra-vated by the fact that internation-al financial institutions (IFIs) had ensured that developing countries were almost entirely invested in the economies of developed coun-tries, creating a situation where the world had all its eggs in one very vulnerable financial basket. If nothing else, the NDB will mean a healthier distribution of power over our globalised economy. The success of an institu-tion is often partly determined by the degree to which its mem-bers are cohesive and united in reaching decisions. But this begs the question – what is it exactly that unites the BRICS countries? Quite simply, the countries have been brought together to form the bank by a shared feeling of ex-clusion from the existing financial system. Labelled the ‘BRIC’ coun-tries by economist Jim O’Neill in 2005, before the inclusion of South Africa in 2010, the acronym was first coined merely to dis-cuss emerging economic powers. What has led these countries to embrace this label and actively pursue a collaborative agenda, however, is that they continue to be overlooked when it comes to decision-making within the IMF and World Bank, despite display-ing impressive growth rates. Nonetheless, the cross-conti-nent coalition remains an unlikely grouping and it is impossible to say whether a shared desire to be recognised on the global fi-nancial stage will be enough to coordinate the five members. The BRICS countries differ widely, not least because their respective economies range hugely in size. And it’s not just geographical and economic differences that could cause potential problems, but political discrepancies too; some members are democracies while others are authoritarian regimes. The Bretton Woods institutions experience enough difficulties in reaching executive decisions whilst being constituted by like-minded liberal democracies. The high rate of corruption in each of the five member coun-tries also signals a red flag, exac-erbated by the prospect of com-peting political agendas. And the sustained track record of human rights abuses held by each coun-try indicates yet another potential threat to the success of the NDB – most notably in Russia, India and China. The leaders of coun-tries with a history of top-level discriminatory violence against minorities like homosexuals and women should not be lauded, but that should not stop us from recognising their progress. The participating countries may be far from perfect in terms of corrup-tion and human rights abuses, but the NDB vision should be taken plainly for what it is – a positive effort towards tackling issues of development and inequalities. Nonetheless, there are three fun-damental things needed to bal-ance this vision against any inter-nal threats: sufficient regulation, leadership and accountability. Nobel Prize winning econo-mist Joseph Stiglitz is exception-ally positive about the future of the BRICS development bank, claiming that the existing insti-tutions have not evolved suffi-ciently enough and insisting that the member countries are un-derestimated in their capabilities in overcoming their differences. Stiglitz argues “in spite of all of the differences, the emerging markets can work together, in a way more effectively than some of the advanced countries can”. The BRICS countries really do have a strong role to play in rebalancing the global economy and the fact remains that there are simply not enough resources being provided by the IMF and the World Bank that allow them to do so. Whether we truly believe in the potential of a New Develop-ment Bank or just support the principle of breaking away from the IFIs that monopolise the global economy, it is important that we remain positive about the creation of a BRICS development bank. Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa may have a lot of difficulties ahead of them, but the encouragement and empow-erment of emerging economies to set up development institutions is no doubt positive. In working to-gether with a common cause, the BRICS countries have everything to prove as a new force: that their whole may be greater than the sum of their diverse parts. A TIME FOR CHANGE... By Dai sy Sibun ...A NEW BRICS DEVELOPMENT BANK Credit: Flickr / worldbank 20 |Centrespread 21

- 12. on rough seas why somalian fisherman It may be on the doorstep of one of the world’s most vital trade routes and been home to some of the most exotic and affluent Kingdoms and Em-pires of the past, but the modern nation of Somalia has been faced with political turmoil, anarchy and famine. Caught up in the Scramble for Africa, the World Wars and the Cold War, Somalia’s history has made a defining impression on the relentless civil war that has suffocated the country for the last 23 years. Britain and Italy granted independence to their protector-ates and territories on the Afri-can Horn and these formed the Republic of Somalia in the early 1960s. In 1969, following the as-sassination of the President, Siad Barre staged a coup that led to a socialist state. The underlying problem, however, is that in many ways Somalian cultural norms fundamentally clashes with the very concept of the state. Barre suffered an inevitable backlash and was overthrown by opposing clans. Disagreements about who had the right to govern led to a power vacuum and, consequently, a bloody civil war. The UN Monitoring Report and analysts such as Martin N Murphy have highlighted how un-regulated fishing by foreign ves-sels after the fall of Barre resulted in the rise in piracy; a develop-ment that cost the world economy around $7bn in 2011. Figures put resulting losses at around $300 million a year with significant depletion of the ocean’s tuna and shrimp. With no effective government to police its waters many turned to ‘defensive piracy’, an act in which local fisherman defended their grounds against these illegal trawlers. It wasn’t un-til 2005 that a sharp rise in ‘pred-atory turn to piracy piracy’ was noted, in which commercial vessels were directly and actively targeted. According to the Wall Street Journal, pirates earned around $150 million in 2008. Moreover, pirates seized a Ukrainian freighter stocked with weapons that same year, demand-ing a ransom of $25 million. Yet, in recent years, the inci-dences of piracy in Somalia have dropped drastically. In 2013 the US Office of Naval Intelligence highlighted that only nine vessels were attacked with no successful hijackings. One reason for this could be the increased military presence and rising numbers of security teams that have protect-ed maritime traders from these at-tacks. Roughly $6bn has been paid in for security equipment, coun-ter- piracy and military operations. The measures have proven to be effective, as figures show that in 2010 $176m was paid in ransoms while in 2012 this had dropped to $31.8m. With armed guards, sound guns, lasers, water canons, electric fences and boat traps, this arsenal has been designed to pro-tect these vessels. However, it does not provide a solution to the problem. Pira-cy is the result of a poverty that stems from an ineffective govern-ment unable to govern its terri-tory. The European Union and development banks have pledged around $8 billion to help devel-op the Horn of Africa recently, yet the challenges facing Somalia appear to overwhelm this pledge. The UN Secretary General Ban Ki- Moon reports that currently fam-ine in Somalia will affect around 3 million people. It is clear that more must be done to help de-velop Somalia if it is to truly be-come a functioning and thriving nation. By Rayha an Iqbal Credit: Flickr / defenceimages AFRICA “Between 2000 and 2012, the lives of an estimated three million chil-dren under age five were saved from malaria due to coordinated inter-ventions in sub-Saharan Africa. The estimated number of new tubercu-losis cases fell from 321 per 100,000 people in 2002 to 255 in 2012. The incidence of new HIV cases in the region fell by more than half between 2001 and 2012.” Credit: Flickr / gbaku Africa | 23